Bakan_Law_110_-_Contracts_Winter_2013_Rachel_Lehman

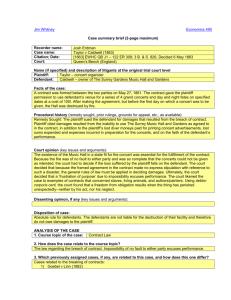

advertisement