The unified Airway

advertisement

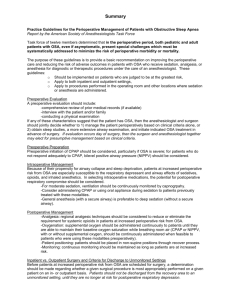

A CPMC Regional CME Event THE UNIFIED AIRWAY - An Integrated Approach Saturday October 1, 2011 SLEEP APNEA: THE SILENT AIRWAY CONTRIBUTOR Brandon Lu, M.D., M.S. San Francisco Critical Care Medical Group OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA • Repetitive upper airway closure during sleep resulting in repeated reversible blood oxygen desaturation and fragmented sleep1,2 • Severity measured by Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI): – Apnea: ≥ 90% decrease in airflow from baseline, for ≥ 10 sec – Hypopnea: ≥ 30% decrease in airflow from baseline, for ≥ 10 sec; accompanied by ≥ 4% desaturation from baseline 1. Young et al., Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165 2. Hiestand et al., Chest 2006;130 3. Iber et al., The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. 2007. OSA: 2-MIN EPOCH OF SLEEP STUDY OSA: SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM • Estimated prevalence: AHI > 5 AHI > 15 Men Women Men Women Wisconsin1 24 9 9 4 Pennsylvania2,4 17 - 7 2 SHHS3 46 18 • Up to 90% of people with OSA are undiagnosed5 1.Young et al., N Engl J Med 1993;328 2.Bixler et al., Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163 3.Nieto et al., JAMA 2000;283 4. Bixler et al., Am J Respir Crit Care Med 198;157 5. Young et al., Sleep 1997;20 OSA: ASSOCIATED MORBIDITIES • Cardiovascular disease • Hypertension, CAD, CHF, arrhythmias, stroke • Metabolic syndrome, diabetes • Daytime sleepiness, e.g. motor vehicle accidents • Dementia • Mood disorder • Mortality SLEEP APNEA AND INTERMITTENT HYPOXEMIA OSA AND THE SYMPATHETIC SYSTEM Somers et al., J Clin Invest 1995;96 OSA: SYMPTOMS AND ASSOCIATED FINDINGS • • • • • • • • • Obese Loud snoring Witnessed apneas Daytime sleepiness Unrefreshing sleep Males Hypertension DM Memory and learning impairments • • • • Hypothyroidism Acromegaly Nasal obstruction Craniofacial abnormalities (i.e., Down’s syndrome, Pierre-Robin syndrome) PHYSICAL EXAMINATION Mallampati classification • Neck size greater than 17.5 inches (men) • BMI greater than 30 • Pharynx - Thick side walls • Uvula - Long • Soft palate - Low • Tonsils - Large • Nasal Obstruction • Retrognathia EPWORTH SLEEPINESS SCALE • How likely are you to fall asleep in the following situations, in contrast to feeling just tired? • • • • 0 = would never doze 1 = slight chance of dozing 2 = moderate chance of dozing 3 = high chance of dozing • >10 indicates daytime sleepiness Johns, Sleep 1994 SITUATION CHANCE OF DOZING Sitting and Reading ____ Watching TV ____ Sitting inactive in a public place (e.g. in a theater or a meeting) ____ As a passenger in a car without a break for an hour ____ Lying down in the afternoon when circumstances permit ____ Sitting and talking with someone ____ Sitting quietly after lunch without alcohol ____ In a car, while stopped for a few minutes in traffic ____ WHEN TO REFER FOR SLEEP STUDY • • • • Loud snoring, witnessed apneas, etc. Daytime sleepiness Physical exam, including obesity Comorbidities (cardiovascular, metabolic, etc) WHAT TO DO BEFORE SLEEP STUDY • Treat nasal obstruction/congestion • Startling Resistor: upstream obstruction leads to suction force downstream • Oral breathing vs. nasal breathing • Oral breathing results in increased upper airway resistance (12.4 vs. 5.2 cmH2O∙L-1∙s-1) and collapse during sleep Smith et al., J Appl Physiol. 1988 Meurice et al., Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996 Fitzpatrick et al., Eur Respir J. 2003. TYPES OF SLEEP STUDY • • • • Diagnostic study Split night study CPAP titration study Home study WHEN TO REFER TO A SLEEP PHYSICIAN • No guideline • Troubleshoot - Mask, pressure, alternate therapeutic options • Follow-up - Medicare guideline requires documentation within 90 days of CPAP initiation: • • Face-to-face evaluation documenting benefit Objective evidence of adherence reviewed by treating physician (>4 hr use on 70% of nights) • Critical mass POSITIVE AIRWAY PRESSURE Types of Home Nocturnal Positive Airway Pressure Devices Type of Device Continuous Pressure Pressure Delivery Unchanged through the night Indication OSA Mechanism Prevents upper airway obstruction Bilevel Pressure Separate inspiratory and expiratory pressure 1) OSA 2) Ventilatory Failure In OSA may increase patient comfort and compliance Auto Pressure Delivered pressure changes breath to breath 1) Estimating CPAP requirements in OSA 2) Improving OSA patient comfort and compliance Measurement of changes in flow are compensated for by increased pressure delivered on a breath to breath basis COMFORT FEATURES OF CPAP: C-FLEX / EPR • PEF sensing allows a reduction in flow during exhalation • Comfort mode • Not for ventilation, only for maintenance of a patent upper airway 10 Pressure 5 0 I E I E I SURGICAL OPTIONS FOR OSA Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) Shortens uvula, trims soft palate, and sutures back the anterior and posterior pharyngeal pillars; tonsillectomy is performed if indicated. Won et al., Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008 Genioglossus advancement Enlarges the hypopharyngeal space by pulling forward the tongue base at the geniotubercle through a mandibular osteotomy SURGICAL OPTIONS FOR OSA Maxillomandibular advancement osteotomy Advances the maxilla and mandible to enlarge the retrolingual and retropalatal spaces Won et al., Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008 Adenotonsillectomy First-line therapy for obstructive sleep apnea in children; both adenoid and tonsillar tissue are removed, and the lateral pharyngeal walls are sutured to prevent collapse PALATAL IMPLANTS http://www.snoring911.com/treatments.php SURGICAL OPTIONS FOR OSA • Tracheostomy: effective; last resort • MMA: severe OSA who can’t use CPAP and OA not an option • UPPP: does not reliably normalize AHI in mod/sev OSA; try CPAP or OA first • Multi-level or stepwise surgery: acceptable in patients with narrowing of multiple sites in the upper airway • LAUP: not routinely recommended (standard) • RFA: can be considered in mild/mod OSA who can’t use CPAP or OA • Palatal implants: may be effective in mild OSA who can’t use CPAP or OA Practice Parameters for the Surgical Modifications of the Upper Airway for Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults. AASM 2010 ORAL APPLIANCES “Oral appliances are indicated for use in patients with mild to moderate OSA who prefer them to CPAP therapy, or who do not respond to, are not appropriate candidates for, or who fail treatment attempts with CPAP…Follow-up polysomnography or an attended cardiorespiratory (Type 3) sleep study is needed to verify efficacy…” AASM, SLEEP, 2006. OSA AND COUGH • 108 consecutive referrals for suspected OSA: 33% of OSA pts reported chronic cough (>2 mos.) predominantly females (61% vs. 17%), more nocturnal heartburn (28% vs. 5%) and rhinitis (44% vs. 14%) compared to those without SDB. • 75 chronic cough pts without pulmonary pathology; 35/38 (92%) who underwent sleep study had OSA; 93% given CPAP and had improvement in cough Chan et al., Eur Respir J. 2010 Sundar et al., Cough 2010 OSA AND GERD • 1116 patients with PSG-diagnosed OSA and 1999 participants in a general health survey: - Weekly nocturnal reflux symptoms present in 10.2% OSA pts vs. 5.5% general population (p<0.001) and 13.9% severe versus 5.1% mild OSA - Frequent nocturnal reflux symptoms were associated with severity of OSA (OR 3.0, severe versus mild OSA, P<0.001) after correcting for multiple factors • Nocturnal reflux associated with transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation (TLESR) but not by negative intra-esophageal pressure during OSA Shepherd et al., J Sleep Res 2011 Kuribiyashi et al., Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010 OSA AND GERD • Patient with OSA and GER showed decreased 24-hr acid contact time after treatment with CPAP Tawk et al., Chest 2006