Rationale and Question Response

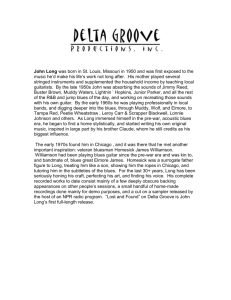

advertisement

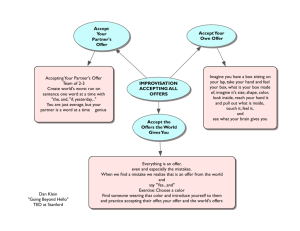

Keith Richardson Dr. Jones June 22, 2015 Project items located at: http://www.ldsd.org/Page/10962 What are some of the strictly musical aspects of the blues that make the study of the genre so compelling? The blues provide a compelling area of study because of the creative spaces delineated by the rules of the form. The AAB blues structure provides room for similar material to contrast with other melodic (or harmonic) ideas. When musicians start to work on building improvisatory skills, the learning curve is relatively slow. As musicians progress, the ideas can get more complex with the addition of more technical melodic material, longer solos, or a greater awareness of the contributions of other band members to the improvisational process. The theoretical background of the blues allows for conversations about how rules can be broken under the right circumstances. Concepts like retrogression, major-minor modal mixture, and constructed scales are all topics that are worthy of examination by those that have the background to dive into the questions that arise out of the standard blues format. Finally, the harmonic underpinnings of the form can be altered or augmented depending on the level of the performer. This can serve as a great bridge to other forms of jazz and a doorway to a greater understanding of theoretical concepts like secondary dominants, chord substitutions, and chord/scale relationships. To what other field(s) can blues study contribute? The blues, as a cultural tradition, have influenced much of the music of the twentieth century. Just as the study of the blues can enhance our understanding of current musical trends, study of the blues and its roots can also expand our understanding of other academic areas, like geography and history. The spread of blues, and jazz, to northern areas of the country like Kansas City, Chicago, and New York, help to place the music in a context that provides a broader understanding (Strait 202, 2012) of both the culture that helped define the blues (postcivil war Afro-American) and the culture to which it greatly contributed (American music history and popular music). The study of the improvisational facet of blues performance helps students to understand cultural ideals outside of their own existence. Higgins and Mantie state that “improvisation is an ability, a culture, and an experience” (40, 2013). Improvisation is a creative ability that allows musicians to contribute culturally as “musically educated people”. Higgins and Mantie further state “we all improvise on something" implying that life itself is an improvisation and being able to handle musical improvisation has the ability to make a person better able to handle improvisatory moments in life. Curricular context This unit on the Blues: History and Practice, was developed for the Jazz Improvisation class at Lower Dauphin High School. The class is offered every other year due to scheduling conflicts. Lower Dauphin HS is a suburban school district between Harrisburg and Hershey, PA with a population of about 1100 students in grades 9-12. Although we have a variety of course offerings, many of the available courses are performance based (band, chorus, and orchestra) and imply that previous membership is needed in order to participate at the HS level. The jazz class seems to be exempt from this perspective, but the improvisation portion of the curriculum appears to intimidate some students. The learning process for improvisation, in addition to some jazz history and basic music theory, is an important facet of the class. Learning about improvisation, and a good method to practice the skill, are two concepts that are of concern to high school students. The process in my class is similar to the process outlined in Tomassetti’s article “Beginning Blues Improvisation Pedagogy for the Non-Jazz Specialist Music Educator” (2003). Basically, improvisers are presented with small pieces of music (4-8 bars) and a few basic rules to guide their thoughts as they begin to create melodies within the given framework. Tomassetti uses the blues because the AAB structure allows room for only two ideas: a question phrase, twice, and an answer phrase. In the class performance assignments, there are two requirements: 1) Improv over the blues chorus provided by the tune being studied and 2) be able to play and embellish the lead sheet for the blues. This framework provides students with the opportunity to improve their ear skills using improvisation and their ability to "fill the space", a defining blues concept, using the head as a starting point. By using the head as a starting point, students can start with a known, visible musical idea and expand the idea melodically before moving into pure improvisation. Aural examples of appropriate material to use for melodic improvisation can come from me, other students, recordings, or the backing tracks. The goal of the backing track and lead sheet are to work the student's abilities to the point where they can focus more on what they are playing (aesthetic decisions) rather than on the creative process that got them there (how do I play anything). This methodology is referenced in Watson's article on improvisation pedagogy, "educators should strongly consider the incorporation of aural imitation tasks and exposure to exemplary models into their improvisation teaching methodologies" (2010, 250). Performances are graded using a rubric that is designed to address improvisation without getting involved in decisions regarding quality of creativity. The class is designed to allow opportunities to discuss performances and the process behind those performances to begin to delineate a procedure for students work through a solo. Questions for self reflection include: what melodic ideas did I aim for? how did I maintain unity and variety throughout the solo? what goal note was I aiming for at the cadence? did I stay within the key? did I mean to? what notes 'didn't fit'? Why? In the end, the rubric is used to help students gauge their progress in learning how improvise and expand their improv vocabulary. Research has shown that critiquing improvisation in this way is valid, "The relatively consistent finding of high correlations among individual dimensions of jazz improvisation achievement may suggest that the designation of a single score to assess achievement is as effective as assessing individual dimensions" (Watson 390, 2010b). The second portion of the unit helps to pull all of the musical elements together into a unified presentation based on an artist or composer of the idiom we are currently studying. The rubric for this portion included elements that require the inclusion historical and cultural references that impacted the artists. These elements could be associated with their childhood or historical era the artist was raised in. The impact of the historical surroundings of the artists should not be overlooked, so I include this type of presentation in each era of jazz we study. Students can begin to see how artists are differently enriched and inspired by their contemporary surroundings. Students also need to complete a performance of the head of one of the artists tunes. They may learn this by ear or by sight, if they can find the music. Part of this performance is a basic analysis of how the tune works: form, common chord structures, progressions, etc. As the students get more advanced, we move into transcription at some level to help reinforce how these musical elements work together. All elements of the unit are designed to lead students to a greater understanding of the blues' role in the larger context of jazz history, an introduction to improvisation, and a introduction to looking a music analytically and critically. Bibliography This listing encompasses ALL areas of the project, not just sources listed in the paper. Hart, David, E. 2011. "Beginning Jazz Improvisation Instruction at the Collegiate Level." DMA diss., University of Rochester. PA Department of Education. 2015. "Pennsylvania Academic Standards 9-12 Band, Music." Accessed June 17. http://www.pdesas.org/Standard/Views#114,115,116,117|795|0|0 Strait, John. 2012. "Experiencing Blues at the Crossroads: A Place-Based Method for Teaching the Geography of Blues Culture." Journal of Geography 111:5, 194-209 DOI: 10.1080/00221341.2011.637228. Tomassetti, Benjamin. 2003. "Beginning Blues Improvisation Pedagogy for the non-Jazz Specialist Music Educator." Music Educators Journal 89:17-21. DOI: 10.2307/3399853 Watson, Kevin. 2010. "Charting Future Directions for Research in Jazz Pedagogy: Implications of the Literature." Music Education Research 12: 383-393. DOI: 10.1080/14613808.2010.519382 Watson, Kevin. 2010. "The Effects of Aural Versus Notated Instructional materials on Achievement and Self-Efficacy in Jazz Improvisation." Journal of Research in Music Education 58:240-259. DOI: 10.1177/0022429410377115