THE LAW - La Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri

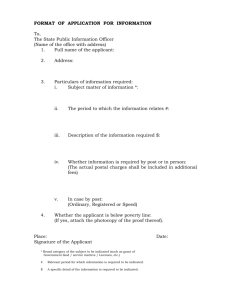

advertisement