Document

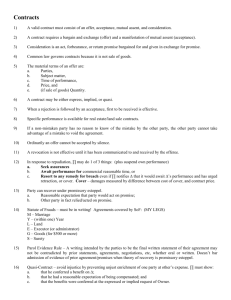

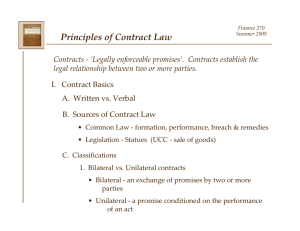

advertisement