1 organization and types of ports

advertisement

РОСЖЕЛДОР

Федеральное государственное бюджетное образовательное учреждение

высшего профессионального образования

«Ростовский государственный университет путей сообщения»

(ФГБОУ ВПО РГУПС)

филиал в г.Туапсе

О.А. Витрук, И.П. Приходько

MERCHANT PORT AND MARINE CARGO TRANSPORTATION

Учебно-методическое пособие

по английскому языку

Ростов-на-Дону

2013

УДК 42(07) + 06

Рецензент – кандидат филологических наук, доцент

Е.А. Белоусова (филиал РГУПС в г. Туапсе)

Витрук, О.А

Merchant Port and Marine Cargo Transportation: учебно-методическое

пособие / О.А. Витрук, И.П. Приходько ; ФГБОУ ВПО РГУПС (филиал в г.

Туапсе). – Ростов н/Д, 2013. – 28 с.

В учебно-методическом пособии описаны основные морские порты, даны

типы грузовых судов, приводится краткая характеристика перевозимых грузов,

условий их погрузки и транспортировки. В пособии даны лексические и

грамматические задания, вопросы для самоконтроля, а также задания для

развития навыков устной речи по теме.

Цель пособия – развитие навыков чтения специальных текстов, их

перевода. Учебно-методическое пособие предназначено для студентов очной и

заочной форм обучения специальности «190600 «Эксплуатация транспортнотехнологических машин и комплексов»». Рекомендовано для подготовки к

практическим занятиям, а также при составлении отчетов о прохождении

учебной практики по английскому языку.

Одобрено к изданию кафедрой «Гуманитарные и экономические

дисциплины» филиала РГУПС в г. Туапсе.

Учебное издание

Витрук Ольга Артемовна

Приходько Инна Павловна

MERCHANT PORT AND MARINE CARGO TRANSPORTATION

Печатается в авторской редакции

Технический редактор М.А. Гончаров

Подписано в печать 17.10.13. Формат 60×84/16.

Бумага газетная. Ризография. Усл. печ. л. 1,63.

Тираж

экз. Изд. № 5089. Заказ

.

Ризография ФГБОУ ВПО РГУПС.

__________________________________________________________________

Адрес университета: 344038, г. Ростов н/Д, пл. им. Ростовского Стрелкового Полка

Народного Ополчения, 2.

© ФГБОУ ВПО РГУПС, 2013

CONTENTS

1 ORGANIZATION AND TYPES OF PORTS ................................................. 4

1.1 Text 1: Types of Ports ................................................................................... 4

1.2 TEXT 2: Organization of Operations in Russian Ports. Functions

of Sea Ports. ................................................................................................................. 8

1.3 Text 3. The Organization of Port in Oslo...................................................... 9

1.4 Text4. Merchant Navy of the United Kingdom of Great Britain

and Northern Ireland.................................................................................................... 10

1.5 ASSIGNMENTS and TASKS .................................................................... 15

2 MERCHANT VESSELS ............................................................................... 17

2.1 Text 1: Name Prefixes of Merchant Vessels ............................................... 17

2.2 Text 2: Merchant ship categories ................................................................ 18

2.3 Text 3. Ship Structure: Exterior .................................................................. 21

2.4 Text 4. Ship Structure: Interior ................................................................... 21

2.5 Text 5: Cargo ships ..................................................................................... 22

2.6 Text 6: The History of Cargo Ships ............................................................ 23

2.7 Text 7:Sizes of cargo ships ......................................................................... 25

2.8 ASSIGNMENTS AND TASKS ................................................................. 26

BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................................................................. 28

1 ORGANIZATION AND TYPES OF PORTS

1.1 Text 1: Types of Ports

A port is a location on a coast or shore containing one or more harbors where

ships can dock and transfer people or cargo to or from land.

Port locations are selected to optimize access to land and navigable water, for

commercial demand, and for shelter from wind and waves. Ports with deeper water

are rarer, but can handle larger, more economical ships. Since ports throughout history handled every kind of traffic, support and storage facilities vary widely, may extend for miles, and dominate the local economy. Some ports have an important military role.

Ports often have cargo-handling equipment, such as cranes (operated by longshoremen) and forklifts for use in loading ships, which may be provided by private

interests or public bodies. Often, canneries or other processing facilities will be located nearby. Some ports feature canals, which allow ships further movement inland.

Access to intermodal transportation, such as trains and trucks, are critical to a port, so

that passengers and cargo can also move further inland beyond the port area. Ports

with international traffic have customs facilities. Harbour pilots and tugboats may

maneuver large ships in tight quarters when near docks.

The terms "port" and "seaport" are used for different types of port facilities

that handle ocean-going vessels, and river port is used for river traffic, such as barges

and other shallow-draft vessels.

An Inland port is a port on a navigable lake, river (fluvial port), or canal with

access to a sea or ocean, which therefore allows a ship to sail from the ocean inland

to the port to load and unload its cargo.

A fishing port is a port or harbour for landing and distributing fish. It may be a

recreational facility, but it is usually commercial. A fishing port is the only port that

depends on an ocean product, and depletion of fish may cause a fishing port to be uneconomical. In recent decades, regulations to save fishing stock may limit the use of a

fishing port, perhaps effectively closing it.

A dry port is an inland intermodal terminal directly connected by road or rail

to a seaport and operating as a centre for the transshipment of sea cargo to inland destinations.

A warm water port is one where the water does not freeze in winter time. Because they are available year-round, warm water ports can be of great geopolitical or

economic interest. Such settlements as Vostochny Port, Murmansk and Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky in Russia, Odessa in Ukraine, Kushiro in Japan and Valdez at the

terminus of the Alaska Pipeline owe their very existence to being ice-free ports.

A seaport is further categorized as a "cruise port" or a "cargo port". Additionally, "cruise ports" are also known as a "home port" or a "port of call". The "cargo

port" is also further categorized into a "bulk" or "break bulk port" or as a "container

port".

A cruise home port is the port where cruise-ship passengers board (or embark)

to start their cruise and disembark the cruise ship at the end of their cruise. It is also

where the cruise ship's supplies are loaded for the cruise, which includes everything

from fresh water and fuel to fruits, vegetable, champagne, and any other supplies

needed for the cruise. "Cruise home ports" are a very busy place during the day the

cruise ship is in port, because off-going passengers debark their baggage and oncoming passengers board the ship in addition to all the supplies being loaded. Currently, the Cruise Capital of the World is the Port of Miami, Florida, closely followed

behind by Port Everglades, Florida and the Port of San Juan, Puerto Rico.

A port of call is an intermediate stop for a ship on its sailing itinerary, which

may include up to half a dozen ports. At these ports, a cargo ship may take on supplies or fuel, as well as unloading and loading cargo. But for a cruise ship, it is their

premier stop where the cruise lines take on passengers to enjoy their vacation.

Cargo ports, on the other hand, are quite different from cruise ports, because

each handles very different cargo, which has to be loaded and unloaded by very different mechanical means. The port may handle one particular type of cargo or it may

handle numerous cargoes, such as grains, liquid fuels, liquid chemicals, wood, automobiles, etc. Such ports are known as the "bulk" or "break bulk ports". Those ports

that handle containerized cargo are known as container ports. Most cargo ports handle all sorts of cargo, but some ports are very specific as to what cargo they handle.

Additionally, the individual cargo ports are divided into different operating terminals

which handle the different cargoes, and are operated by different companies, also

known as terminal operators or stevedores.

Ports sometimes fall out of use. Rye, East Sussex, was an important English

port in the Middle Ages, but the coastline changed and it is now 2 miles (3.2 km)

from the sea, while the ports of Ravenspurn and Dunwich have been lost to coastal

erosion. Also in the United Kingdom, London, on the River Thames, was once an

important international port, but changes in shipping methods, such as the use of containers and larger ships, put it at a disadvantage.

Fig.1.This marina in Beachlands, New Zealandhas yachts in rows as well as

ferryboat service to the central business district of Auckland.

Fig. 2.Engl. harbour = Am. harbor

the harbour hospital:

18 the pleasure steamer (excursion

steamer)

the quarantine station

19 the harbour launch

the institute for tropical diseases

20 the barge (lighter)

(for tropical medicine)

the meteorological offices (Am.

21 the tug (steam tug, tug boat, tow

Weather

boat)

bureau), a meteorological station:

5 the signal mast

22 the sea-going barge or lighter

6 the storm signal (storm warning)

23 the bunkering tanker

7 the harbour quarter

24 the harbour ferry (ferry boat)

8-12 the fishing harbor (fishing25 the harbour industry

port)

the net factory

26 the inner harbor

the cannery

27 the harbour canal

10 the packing shed

28 the transit shed

11 the fish auction market

29 the water boat

12 the equipment shed;

30 the lighter

13 the harbour office

31 the warehouse;

14 the water level indicator

32-36 the quay (wharf):

15 the quay road

32 the mole (jetty)

16 the passenger quay

33 the landing stage (pontoon)

34 the harbour customs house

35 the banana shed

the landing pier (landing stage)

Fig.3. (continued)

36.the fruit shed;

37.the dolphins

38.the storage shed

39.the conveyor belt

40.the cold-storage house

41-43 the free port boundary

53 the jib (boom, atm);

54 a timber ship:

55 the deck cargo (deck load);

56 and 57 the timber wharf:

56 the timber storage sheds

57 the timber stock (A.m. lumber

wharf);

41.the customs fence and 43

58 the harbour light

the customs entrance

42.the customs barrier

59-62 the oil wharf (mineral oil

wharf, petroleum wharf):

43.the customs house;

59.the pipe bridge,

44-53 the bulk goods wharf

60 the intermediate tank

44.the silos:

61 the storage tank

45.the silo bin;

62 the safety dam;

46-53 the coal wharf:

63 and 64 the banana elevator:

(Am. harbor railroad)

46.the elevated weighing bun-

63 the conveyor belt

ker

47.theharbour railway

48.the coal depot

49-51 the coaling station:

49.the shunting platform

50.the coal chute

51.the falling track;

64 the conveyor bucket;

65 the banana cluster ('stick' of bananas)

66-68 the coal chute crane:

66 the lift platform (Am. elevator

platform)

67 the boom (jib)

68 the coal distributor (coal trimmer)

52.the loading bridge (gantry)

1.2 TEXT 2: Organization of Operations in Russian Ports. Functions

of Sea Ports.

Russian merchant sea ports are under the authority of the Ministry of Merchant

Marine of Russia and are intended to perform economic and administrative functions.

THE ECONOMIC FUNCTIONS. Sea ports are responsible for loading/unloading operations, servicing of inbound/outbound Russian and foreign ships,

transportation, forwarding and warehousing operations, transshipment of cargo to the

marine transport from other modes of transport (i.e. intermodal cargo handling operations), servicing of deep sea vessels passengers. To perform these functions sea

ports have water areas, land territories, warehouses and open storage facilities, cargo

handling facilities, passenger terminals, approach ways for railway and motor

transport, and an adequate personnel.

THE ADMINISTRATIVE FUNCTIONS. Sea ports are responsible for ensuring safe navigation and proper order within the port, including supervision for adherence to shipping regulation of vessels in the State Register of Shipping, issue and

check up of ship’s papers, diploma and qualification certificates of ship officers,

clearance of vessels inwards and outwards, organization of pilotage and towering

service and other functions of Port Operation Management.

Port operation management is effected by three channels. The higher channel

controls port operations as a whole and includes the operations commerce, shipping,

planning, labour and wages, merchanization, technology personnel, accounts, administrative, harbor master’s and other functional services and departments.

The port is headed by the General Director who controls the entire port operations. Each department or service is managed by the department head. There are also

some deputy general directors. Thus the deputy general director operational is responsible for the operations, commerce and shipping departments.

Safety of shipment and proper order in the port are the responsibility of the

harbor master who is a deputy general director at the same time.

The middle channel of management controls cargo handling complexes and

other production units of the port such as port auxiliary service fleet, depots for motor

and electric lift trucks, railway and motor cars, etc., repair and maintenance shops,

rigging shops and others. The main production units of the port are cargo handling

complexes where all loading/unloading operations are carried out. The complexes

specialize in handling specific types of cargoes (general cargo, timber, ore, containers, liquid cargoes, etc.) and in serving specific cargo traffic routes.

Each cargo handling complex comprises terminals, complex stevedore gangs,

traffic control service, warehouse and open storage personnel, and is headed by the

superintendent. The lower channel of the management is involved in a direct control

of cargo handling operations on berths and in warehouses. This control is effected by

chief stevedores, warehouse superintendents and stevedore gang foremen.

All Russian ports, like any other ports, are provided with information computing centres equipped with most up-to-date sophisticated computers. As a result, lots

of problems are solved by computers, for example, drawing up cargo plans and optimal technological plans-schedules for handling a particular vessel, drawing up shiftday plans-schedules of the port operations and operations of each particular cargo

handling complex.

1.3 Text 3. The Organization of Port in Oslo

Oslo is Norway’s busiest ferry port with four daily departures to Denmark and

Germany. The ferries carry over 2.6 million passengers a year and 1.2 million tons of

freight. The freight carried by these ferries constitutes a third of the general cargo

handled by the port of Oslo.

Ferry traffic into and out of Oslo is expanding all the time with newer and ever

larger ferries being taken into service.

This expansion makes it imperative for the port to have efficient, up-to-date

terminal buildings and also adequate space for vehicle ferry lines and for customer

facilities for disembarking vehicles. Container transport is an expanding segment of

the port of Oslo.

The port currently has two container terminals, but development is underway to

bring all container handling into one single terminal. When completed, this terminal

will have a total quay length of 700 metres with a minimum water depth of 12 metres.

1.4 Text4. Merchant Navy of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and

Northern Ireland

Fig. 4.Badge of the British Merchant Navy

Merchant Navy

of the United Kingdom

The Merchant Navy is the maritime register of the United Kingdom, and describes the seagoing commercial interests of UK-registered ships and their crews.

Merchant Navy vessels fly the Red Ensign and are regulated by the Maritime and

Coastguard Agency (MCA). King George V bestowed the title of "Merchant Navy"

on the British merchant shipping fleets following their service in the First World

War; a number of other nations have since adopted the title.

History

The Merchant Navy has been in existence for a significant period in British

history, owing much of its growth to British imperial expansion. As an entity in itself

it can be dated back to the 17th century, where an attempt was made to register all

seafarers as a source of labour for the Royal Navy during times of conflict. That registration of merchant seafarers failed, and it was not successfully implemented until

1835. The merchant fleet grew over successive years to become the world's foremost

merchant fleet, benefiting considerably from trade with British possessions in India

and the Far East. The lucrative trade in sugar, spices and tea (carried by ships such as

the CuttySark) helped to solidify this dominance in the 19th century.

During the First and Second World Wars, the Merchant Service suffered heavy

losses from German U-boat attacks. A policy of unrestricted warfare meant that merchant seafarers were also at risk of attack from enemy ships. The tonnage lost to Uboats during the First World War was around 7,759,090 tons,[2] and around 14,661

merchant seafarers lost their lives. In honour of the sacrifice made by merchant seafarers during the First World War, King George V granted the title "Merchant Navy"

to the service. The Prince of Wales was made the Master of the Merchant Navy.

In the Second World War, German U-boats sank nearly 14.7 million tons of allied shipping, which amounts to 2,828 ships (around two thirds of the total allied tonnage lost). The United Kingdom alone suffered the loss of 11.7 million tons, which is

54 % of the total Merchant Navy fleet at the outbreak of the Second World War.

32,000 merchant seafarers were killed aboard convoy vessels during the war, but

along with the Royal Navy, the convoys successfully imported enough supplies to allow an Allied victory.

Fig. 5.The British steamer Andex sinking after being torpedoed by a U-boat.

In honour of the sacrifices made during the two World Wars, the Merchant Navy lays wreaths of remembrance alongside the armed forces during the annualRemembrance Day service on 11 November. Following many years of lobbying to bring

about official recognition of the sacrifices made by merchant seafarers in two world

wars and since, Merchant Navy Day became an official day of remembrance on 3

September 2000.

Despite maintaining its dominant position for considerable time, the decline of

the British Empire in the mid-20th century inevitably led to the decline of the merchant fleet. This is shown in the following table, comparing certain vessel types in

1957 and 2013:

MerchantNavy: 1957 and 2013

ShipType

1957 2013

Passengervessels 322

37 (including ROROs)

Generalcargoships 1,145 55

Tankers

575

88

Total

2042 180

As of 2005, the Merchant Navy consists of 429 ships of 1,000 gross register

tons (GRT) or over; a total of 9,181,284 GRT. This amounts to 9,566,275 metric tons

deadweight (DWT). These vessels can be categorized as follows:

18 bulk carriers

55 general cargo ships

48 chemical tankers

134 container ships,

11 liquefied gas carriers

12 passenger ships

64 combination passenger/cargo ships

40 petroleum tankers

19 refrigerated cargo ships

25 roll-on/roll-off ships

3 vehicle carriers.

In addition, UK interests own 446 ships registered in other countries, and 202

foreign-owned ships are registered in the UK.

Officers past and present

Fig. 6.A recent example of Merchant Navy Officers, graduating at their 'passing out' ceremony from Warsash Maritime Academyin Southampton, with Former

First Sea LordAlan West, Baron West of Spithead, in 2011.

A person hoping to one day become a captain, or master prior to about 1973,

had five choices. To attend one of the three elite naval schools from the age of 12, the

fixed-base HMS Conway and HMS Worcester or Pangbourne Nautical College,

which would automatically lead to an apprenticeship as a seagoing cadet officer; apply to one of several training programmes elsewhere, or go to sea immediately by applying directly to a merchant shipping company at perhaps the age of 17 (with poor

prospects of being accepted without some nautical school or other similar prior education.) Then there would be three years (with prior training or four years without) of

seagoing experience aboard ship, in work-clothes and as mates with the deck crew,

under the direction of the bo'sun cleaning bilges, chipping paint, polishing brass, cement washing freshwater tanks, and holystoning teak decks, and studying navigation

and seamanship on the bridge in uniform, under the direction of an officer, before

taking exams to become a second mate. With luck, one could become an "uncertificated" second mate in the last year.

The modern route to becoming a deck or engineer officer comprises a total of

three years of which at least twelve (six for engineers) months is spent at sea and the

remainder at a sea college. This training still encompasses all of the traditional trades

such as celestial navigation, ship stability, general cargo and seamanship, but now includes training in business, legislation, law, and computerisation for deck officers and

marine engineering principles, workshop technology, steam propulsion, motor (diesel) propulsion, auxiliaries, mechanics, thermodynamics, engineering drawing, ship

construction, marine electrics as well as practical workshop training for engineering

officers. Training is now undertaken at Warsash Maritime Academy, Shetland School

of Nautical Studies, South Tyneside College, Glasgow College of Nautical Studies

and Fleetwood Nautical Campus. As well as earning an OOW (Officer of the Watch)

certificate, they gain valuable training at sea and an HND or degree in their chosen

discipline. The decrease of officer recruiting in the past, combined with the huge expansion of trade via shipping is causing a shortage of officers in the UK, traditionally

a major seafaring nation, and as such a scheme called Maritime UK has been

launched to raise general awareness of the Merchant Navy in the modern day roles.

Another essential seagoing career was that of the radio officer (or R/O, but

usually "sparks"), often, though not exclusively, employed and placed by the Marconi

Company or one of a number of similar radio company employers. After the inquiry

into the sinking of the RMS Titanic, and the nearby SS Californian which did not

render assistance due to their radio being down for the night, it was ordered that

round-the-clock watch had to be maintained on all ships over 1600 GT. Most vessels

only carried one radio officer, and during the hours he was off-duty, an automatic

alarm device monitored the distress frequency. Today, Marconi no longer supplies

radio officers to ships at sea, because they are no longer required, due to the development of satellites. Deck officers are now dual trained as GMDSS officers, thereby

being able to operate all of the ship's onboard communication systems and ETOs

(Electro Technical Officer) are trained to fix and maintain the more complex systems.

COMSAT launched their first commercial satellite in 1976 and by the mid

1980s satellite communication domes had become a familiar sight at sea. The Global

Maritime Distress and Safety System or GMDSS was introduced and by 1 February

1999, all ships had to be fitted, thus bringing to an end the position of radio officer.

This has led to a new career path, the recently introduced electro-technical officer

(ETO), who is a trained engineer with qualifications to assist the mechanical engineer

to maintain vital electronic equipment such as radios and RADARs. ETOs are marine

engineers given extra training. Although ETOs are relatively new, many companies

are beginning to employ them, (although mechanical engineers are still employed).

Sailing on the high seas has a long history, with embedded traditions largely inherited

from the days of sail. Because of the ever-present concerns of safety for crew and

passengers, the layers of authority are rigid, discipline strict, and mutiny almost unknown.

Merchant mariners are held in high esteem as a result of their extraordinary

losses in times of war. The ships were often "sitting ducks" lined up in the sights of

enemy combatants.

Composition of crew

Ship crews work under the eyes of the officers; the deck crew and bo'sun, responsible for general maintenance, sailing "before the mast", (which, due to exaggerated pitching motion in bad weather, is the least comfortable part of the ship). Other

duties aboard ship are performed by the ship's carpenter, the cooks, the stewards, the

quartermaster who steers the ship, and the below-decks crew, often referred to as

"greasers". Ocean-going vessels with more than 12 passengers are required to have a

doctor aboard.

For ships of the British Merchant Navy on foreign service, it used to be that

each of these departments were peopled by different groups. The deck crew would

often be Malay, the quartermasters Filipino, the greasers and stewards Indian, the

cooks Indian but from Goa where, being Christian, they could prepare Western style

food, and the ship's carpenter ("chippy") would often be Chinese. The officers would

be British or Commonwealth, headed by the captain (or master, but more often referred to as "the old man"). The purser was in charge of the ship's stores.

Nowadays, ships have turnaround times of less than twenty-four hours instead

of several days, due to containerisation, requiring a much smaller crew. The passenger liners that once transported people now ply the oceans for pleasure seekers, cargo

ships have switched to containers using efficient shoreside cranes instead of the ship's

derricks, and tankers have become gigantic supertankers.

Notable people

A number of notable Merchant Navy personnel include:

Joseph Conrad: joined the Merchant Navy in 1874, rising through the ranks

of Second Mate and First Mate, to Master in 1886. Left in order to write professionally, becoming one of the twentieth-century's greatest novelists.

Arthur Phillip: joined the Merchant Navy in 1751 and 37 years later founded

the city of Sydney, Australia.

Ken Russell: directed films such as Tommy, Altered States, and The Lair of

the White Worm.

Kevin McClory: an Irishman who spent fourteen days in a lifeboat and later

went on to write the James Bond movies Never Say Never Again and Thunderball.

Alun Owen: later wrote the screenplay for A Hard Day's Night.

Victoria Drummond: MBE, (1894-1978) Britain's first woman ship's engineer.

Frank Laskier: WWII Merchant Navy steward who became a public icon for

recruitment efforts.

Chris Braithwaite (c.1885-1944): seafarers' organiser and Pan-Africanist.

Freddie Lennon: a Merchant Navy steward whose son John would later

found the musical group The Beatles.

Violet Jessop: stewardess who survived Titanic sinking, and author of autobiography about sailing.

John Prescott: a Merchant Navy steward who became Deputy Prime Minister in 1997 under Tony Blair.

Fred Blackburn: England footballer.

Edwin Stratton: founder of Yoshinkan UK.

Air Marshal Sir Peter Horsley: Deputy Commander in Chief (Strike Command) from 1973 - 1975. Started work as a deck boy in 1939 aboard the TSS Cyclops.

Gareth Hunt: actor, notably in The New Avengers, and Upstairs, Downstairs

Members of the British Merchant Navy have won the George Cross and the

Distinguished Service Cross while serving in the Merchant Navy. Canadian Philip

Bent, ex-British Merchant Navy, joined the British Army at the outbreak ofWorld

War I, and won the Victoria Cross.

British shipping companies

The British Merchant Navy consists of various private shipping companies.

Over the years many companies have come and gone, merged, changed their name or

changed owners.

1.5 ASSIGNMENTS and TASKS

I. Read text 1.Translate it into Russian. Answer the following questions:

1. What is a port? Give the definition of a port.

2. What types of ports do you know?

3. What is the difference between inland port and seaport?

II. Read text 2. Translate it into Russian. Prepare excellent reading of the text.

Learn new words and expressions.

III. Using text 2,translate the following word-combinations:

Model: information computing center – информационно-вычислительный

центр

Storage facilities, cargo handling facilities, approach ways, port operations,

port operations management, production unit, stevedore gang, stevedore gang foremen, everyday management problems, warehouse and open storage personnel.

IV. Make up your own sentences using the following word combinations.

То be under authority

То be intended

To be responsible

To insure order

To adhere to regulations

To issue documents

To be involved in

To facilitate

To improve port management

To draw up a plan

To solve a problem

V. Agree with the statement using Passive Voice.

Model: – I think the general director controls the entire port operations.

– Yes, you are right. The entire port operations are controlled by him.

I think the department head manages one particular service.

So far as I understand the deputy director manages several services.

The deputy general director in operations heads the operations, commerce and

shipping

services.

The harbour master controls safety of shipping or order in the port.5. The superintendent heads one cargo handling complex.

VI. Find English equivalents to the following words and phrases:

отдел / служба

коммерческий отдел

служба / отдел эксплуатации

отдел планирования

отдел труда и заработной платы

отдел кадров

отдел механизации

начальник порта

зам. начальника порта

начальник отдела

начальник склада

производственное подразделение

VII. Agree with the following statements using the model.

Model: – Sea ports are responsible for cargo operations, (for servicing ships)

Yes, and they are responsible for servicing ships as well.

Sea ports have all necessary cargo handling facilities (an adequate personnel).

Sea ports service all inbound / outbound Russia vessels (foreign vessels).

The harbour master ensures safe navigation within the port water area (proper

orderwithin the port).

The cargo handling complex comprises terminals and traffic control service

(stevedoregangs and warehouse personnel).

Cargo handling operations are directly controlled by chief stevedore (gang

foremen).

VIII. Ask questions using the prompts.

Model: functions / merchant sea ports / are intended for?

1.What economic / administrative functions / merchant sea ports?

2.Who / the port / headed by?

3.What functional departments / include?

4.What department / deputy general director / responsible for?

5.What production units / there are / in ports?

6.What cargo handling complex / comprise?

IX. Read and discuss text 3. Find the synonyms of these words in text 3.

Full of people and goods

Managed

Important

Modern

Growing

X. Read text 3 about the port of Oslo and choose the best title for each paragraph.

The trend in ferry traffic,

General description of the port of Oslo.

Future development.

Key issues for the expansion of the port.

XI. Read and complete the text. Choose the following words.

Overseas

Sheds

Handling

Shuttle

Equipped

Fuel

Consumption

Increase

The terminals are 1._____ with two gantry cranes each. Container 2.______ at

the terminal is carried out by straddle carriers and R.T.G. (rubber-tyred gantry)

cranes. Most containers are 3.______ cargo, but the volume of short-sea shipping

containers is increasing. Forty-six thousand new cars are unloaded each year in the

port of Oslo. There are two port 4.________ for storage of new cars and unloading

track for further distribution by rail with departures every day. The port off Oslo

handles a large volume of dry bulk. An 5. _________ in construction work in the

whole of Eastern Norway has resulted in heavy demand for cement and sand. The

port has two quays for oil tankers. As much as forty per cent of Norway’s 6._______

of oil products is unloaded at Oslo and stored in storage units. Air traffic in Eastern

Norway is also dependent on the port of Oslo, which receives all the jet 7.______

used at Oslo’s Gardermoen airport. The fuel is then freighted to the airport by a daily

rail 8.______.

XII. Read and discuss text “Marine Navy of the UK”. Find further information

about Marine Navy of the United Kingdom and some other countries in the Internet.

What is the difference between them?

2 MERCHANT VESSELS

2.1 Text 1: Name Prefixes of Merchant Vessels

A merchant vessel is a ship that transports cargo or passengers. The closely related term commercial vessel is defined by the United States Coast Guard as any vessel (i.e. boat or ship) engaged in commercial trade or that carries passengers for hire.

This would exclude pleasure craft that do not carry passengers for hire or warships.

They come in a myriad of sizes and shapes from twenty-foot inflatable dive

boats in Hawaii, to 5,000 passenger casino vessels on the Mississippi River, to tugboats plying New York Harbor, to 1,000 foot oil tankers and container shipsat major

ports, to a passenger carrying submarine in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Most countries of the world operate fleets of merchant ships. However, due to

the high costs of operations, today these fleets are in many cases sailing under the

flags of nations that specialize in providing manpower and services at favourable

terms. Such flags are known as "flags of convenience". Currently, Liberia and Panama are particularly favoured. Ownership of the vessels can be by any country, however.

The Greek-owned fleet is the largest in the world. Today, the Greek fleet accounts for some 16 per cent of the world’s tonnage; this makes it currently the largest

single international merchant fleet in the world, albeit not the largest in history.

In English, "Merchant Navy" without further clarification is used to refer to the

British Merchant Navy; the United States merchant fleet is known as the United

States Merchant Marine.

During wars, merchant ships may be used as auxiliaries to the navies of their

respective countries, and are called upon to deliver military personnel and material.

Merchant ships names are prefixed by which kind of vessel they are:[

MV = Motor Vessel

SS = Steam Ship

MT = Motor Tanker or Motor Tug Boat

MSV = Motor Stand-by Vessel

MY = Motor Yacht

RMS = Royal Mail Ship

RRS = Royal Research Ship

SV = Sailing Vessel (although these can be sub coded as type of sailing vessel)

LPG = Gas carrier transporting liquefied petroleum gas[citation needed]

LNG = Gas carrier transporting liquefied natural gas[citation needed]

CS = Cable Ship or Cable layer

2.2 Text 2: Merchant ship categories

Merchant ships may be divided into several categories, according to their purpose and/or size.

Fig.7. Sabrina I carries bulk cargo inside her holds

A cargo ship or freighter is any sort of ship or vessel that carries cargo, goods,

and materials from one port to another. Thousands of cargo carriers ply the world's

seas and oceans each year; they handle the bulk of international trade. Cargo ships are

usually specially designed for the task, often being equipped with cranes and other

mechanisms to load and unload, and come in all sizes.

Dry cargo ships today are mainly bulk carriers and container ships. Bulk carriers or bulkers are used for the transportation of homogeneous cargo such as coal,

rubber, copra, tin, and wheat. Container ships are used for the carriage of miscellaneous goods.

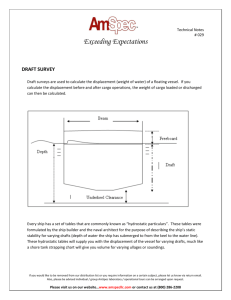

A bulk carrier is an ocean-going vessel used to transport bulk cargo items such

as iron ore, bauxite, coal, cement, grain and similar cargo. Bulk carriers can be recognized by large box-like hatches on deck, designed to slide outboard or fold foreand-aft to enable access for loading or discharging cargo. The dimensions of bulk

carriers are often determined by the ports and sea routes that they need to serve, and

by the maximum width of the Panama Canal. Most lakes are too small to accommodate bulk carriers, but a large fleet of lake freighters has been plying the Great Lakes

and St. Lawrence Seaway of North America for over a century.

Fig. 8.The Colombo Express, one of the largest container ships in the world, owned

and operated by Hapag-Lloyd of Germany

Container ships are cargo ships that carry all of their load in truck-size containers, in a technique called containerization. They form a common means of commercial intermodal freight transport.

Fig. 9.Commercial crude oil supertanker AbQaiq.

A tanker is a ship designed to transport liquids in bulk.

Oil tankers for the transport of fluids, such as crude oil, petroleum products,

liquefied petroleum gas, liquefied natural gas and chemicals, also vegetable oils, wine

and other food - the tanker sector comprises one third of the world tonnage.

Tankers can range in size from several hundred tons, designed for servicing

small harbours and coastal settlements, to several hundred thousand tons, with these

being designed for long-range haulage. A wide range of products are carried by tankers, including:

– hydrocarbon products such as oil, LPG, and LNG$;

– Chemicals, such as ammonia, chlorine, and styrene monomer;

– fresh water;

– wine.

Different products require different handling and transport, thus special types

of tankers have been built, such as "chemical tankers" and "oil tankers". Gas Carriers

such as ""LNG carriers" as they are typically known, are a relatively rare tanker designed to carry liquefied natural gas.

Among oil tankers, supertankers were designed for carrying oil around the

Horn of Africa from the Middle East; the FSO Knock Nevis being the largest vessel

in the world, a ULCC supertanker formerly known as Jahre Viking (Seawise Giant).

It has a deadweight of 565 thousand metric tons and length of about 500 meters. The

use of such large ships is in fact very unprofitable, due to the inability to operate them

at full cargo capacity; hence, the production of supertankers has currently ceased.

Today's largest oil tankers in comparison by gross tonnage are TI Europe, TI Asia, TI

Oceania, which are the largest sailing vessels today. But even with their deadweight

of 441,585 metric tons, sailing as VLCC most of the time, they do not use more than

70% of their total capacity.

Apart from pipeline transport, supertankers are the only method for transporting large quantities of oil, although such tankers have caused large environmental

disasters when sinking close to coastal regions, causing oil spills. See Braer, Erika,

Exxon Valdez, Prestige and Torrey Canyon for examples of tankers that have been

involved in oil spills.

Specialized ships, e.g. for heavy lift goods or refrigerated cargo (Reefer ships),

roll-on/roll-off cargo (RoRo) ships for vehicles and wheeled machinery. These ships

are not very well developed, except those used as car carriers. Only this sector of

Maritime Industry is well developed. The currently largest roll-on/roll-off cargo (RoRo) ships are Sunbelt Spirit, Liberty (ex-Faust), Phoenix Leader and Aquamarine

ACE, each capable of carrying between six and nine thousand units. Another type of

specialised ship is the Cable Ship or Cable layer. These are deep-sea vessels designed

and used to lay underwater cables for telecommunications, electric power transmission, or other purposes. In addition to cable layer ships, there are cable repairing ships

which are tasked with finding and repairing under sea cables that break or for whatever reason became inoperable.

Coasters, smaller ships for any category of cargo which are normally not on

ocean-crossing routes, but in coastwise trades. Coasters are shallow-hulled ships used

for trade between locations on the same island or continent. Their shallow hulls mean

that they can get through reefs where seagoing ships usually cannot (seagoing ships

have a very deep hull for supplies and trade etc.).

A passenger ship is a ship whose primary function is to carry passengers. The

category does not include cargo vessels which have accommodations for limited

numbers of passengers, such as the formerly ubiquitous twelve-passenger freighters

in which the transport of passengers is secondary to the carriage of freight. The type

does however include many classes of ships which are designed to transport substantial numbers of passengers as well as freight. Indeed, until recently virtually all ocean

liners were able to transport mail, package freight and express, and other cargo in addition to passenger luggage, and were equipped with cargo holds and derricks, kingposts, or other cargo-handling gear for that purpose. Modern cruiseferries have car

decks for lorries as well as the passenger's cars. Only in more recent ocean liners and

in virtually all cruise ships has this cargo capacity been removed.

A cruise ship or a cruise liner is a passenger ship used for pleasure voyages,

where the voyage itself and the ship's amenities are considered an essential part of the

experience. Cruising has become a major part of the tourismindustry, with millions of

passengers each year as of 2008. The industry's rapid growth has seen nine or more

newly built ships catering to a North American clientele added every year since 1978,

as well as others servicing Europeanclientele. Smaller markets such as the AsiaPacific region are generally serviced by older tonnage displaced by new ships introduced into the high growth areas.Cruise ships operate on a mostly set roundabout

course or round trips (i.e., they tend to return to their originating port) whereas ocean

liners are defined by actually doing ocean-crossing voyages, which may not lead back

to the same port for years.

Fig. 10.The ferryboat at Kei Mouth with the former Transkei opposite on the

eastern bank, ca.2006.

A ferry is a form of transportation, usually a boat or ship, but also other forms,

carrying (or ferrying) passengers and sometimes their vehicles. Ferries are also used

to transport freight (in lorriesand sometimes unpowered freight containers) and even

railroad cars (in the case of a train ferry). Most ferries operate on regular, frequent,

return services. A foot-passenger ferry with many stops, such as in Venice, is sometimes called a waterbus or water taxi.

Ferries form public transport systems of many waterside cities, allowing direct

transit between points at a capital cost much lower than bridges or tunnels.

2.3 Text 3. Ship Structure: Exterior

A ship must be durable and balanced to handle long periods at sea. The hull

needs strong shell plating. Areas below the waterline up to the freeboard must resist constant water pressure. Higher up, solid bulwarks are needed to protect the

weather deck.

A ship’s superstructures must withstand powerful wind and sea spray. A

well-maintained mast is especially important to keep safety lights working. underneath the ship, the propeller powers the ship. Proper maintenance of these screws

prevents serious failures at sea.

Staying upright is a vital function of a ship’s design. The weight of the keel

centers the ship. The stem extends from the keel to the forecastle, keeping balance at

the ship’s front. The sternpost extends from the keel to the fantail, keeping balance

at the rear.

2.4 Text 4. Ship Structure: Interior

The ship that takes on too much water is doomed to sink. But the interiors of

ships are designed to prevent such a disaster.

A ship is separated into small compartments. Partitions separate passageways from each compartment. Special partitions called bulkheads have watertight

doors. They keep water from reaching other compartments.

The floors of each deck and level are also separated from each other. Closed

hatches seal off each deck’s overhead to prevent the spread of water. When open,

hatches allow sailors to move between decks on ladders. The ship's command centre

sits on the highest platform. Here, captain and crew can survey conditions in all directions.

Seawater is allowed into certain areas, such as the head, to wash out waste. Of

course, this incoming water is carefully controlled with valves and pumps.

2.5 Text 5: Cargo ships

Fig. 11.The Colombo Express, one of the largest container ships in the world

(when she was built in 2005), owned and operated by Hapag-Lloyd of Germany

Fig. 12. Cargo fleet in 2013.

A cargo ship or freighter is any sort of ship or vessel that carries cargo, goods,

and materials from one port to another.

Thousands of cargo carriers ply the world's seas and oceans each year; they

handle the bulk of international trade. Cargo ships are usually specially designed for

the task, often being equipped with cranes and other mechanisms to load and unload,

and come in all sizes. Today, they are almost always built of welded steel, and with

some exceptions generally have a life expectancy of 25 to 30 years before being

scrapped.

Fig. 13.Loading of a general cargo vessel 1959

Cargo ships/freighters can be divided into five groups, according to the type of

cargo they carry. These groups are:

General Cargo Vessels

Tankers

Dry-bulk Carriers

Multipurpose Vessels

Reefer Ships

General Cargo Vessels carry packaged items like chemicals, foods, furniture,

machinery, motor- and military vehicles, footwear, garments, etc.

Tankers carry petroleum products or other liquid cargo.

Dry Bulk Carriers carry coal, grain, ore and other similar products in loose

form.

Multi-purpose Vessels, as the name suggests, carry different classes of cargo

– e.g. liquid and general cargo – at the same time. A Reefer (or Refrigerated) ship is

specifically designed[1] and used for shipping perishable commodities which require

temperature-controlled, mostly fruits, meat, fish, vegetables, dairy products and other

foodstuffs.

Specialized types of cargo vessels include container ships and bulk carriers

(technically tankers of all sizes are cargo ships, although they are routinely thought of

as a separate category). Cargo ships fall into two further categories that reflect the

services they offer to industry: liner and tramp services. Those on a fixed published

schedule and fixed tariff rates are cargo liners. Tramp ships do not have fixed schedules. Users charter them to haul loads. Generally, the smaller shipping companies and

private individuals operate tramp ships. Cargo liners run on fixed schedules published

by the shipping companies. Each trip a liner takes is called a voyage. Liners mostly

carry general cargo. However, some cargo liners may carry passengers also. A cargo

liner that carries 12 or more passengers is called a combination or passenger-cumcargo line.

2.6 Text 6: The History of Cargo Ships

The earliest records of waterborne activity mention the carriage of items for

trade; the evidence of history and archaeology shows the practice to be widespread by

the beginning of the 1st millennium BC, and as early as the 14th and 15th centuries

BC small Mediterranean cargo ships like those of the 50 foot long (15 – 16 meter)

Uluburun ship were carrying 20 tons of exotic cargo; 11 tons of raw copper, jars,

glass, ivory, gold, spices, and treasures from Canaan, Greece, Egypt, and Africa. The

desire to operate trade routes over longer distances, and throughout more seasons of

the year, motivated improvements in ship design during the Middle Ages.

Before the middle of the 19th century, the incidence of piracy resulted in most

cargo ships being armed, sometimes quite heavily, as in the case of the Manila galleons and East Indiamen. They were also sometimes escorted by warships.

Piracy is still quite common in some waters, particularly in the Malacca Straits,

a narrow channel between Indonesia and Singapore / Malaysia, and cargo ships are

still commonly targeted. In 2004, the governments of those three nations agreed to

provide better protection for the ships passing through the Straits. The waters off Somalia and Nigeria are also prone to piracy, while smaller vessels are also in danger

along parts of the South American, Southeast Asian coasts and near the Caribbean

Sea.

Fig. 14. A Delmas container ship unloading at the Zanzibar port in Tanzania

The words cargo and freight have become interchangeable in casual usage.

Technically, "cargo" refers to the goods carried aboard the ship for hire, while

"freight" refers to the compensation the ship or charterer receives for carrying the

cargo.

Generally, the modern ocean shipping business is divided into two classes:

Liner business: typically (but not exclusively) container vessels (wherein "general cargo" is carried in 20 or 40-foot containers), operating as "common carriers",

calling a regularly published schedule of ports. A common carrier refers to a regulated service where any member of the public may book cargo for shipment, according

to long-established and internationally agreed rules.

Tramp-tanker business: generally this is private business arranged between the

shipper and receiver and facilitated by the vessel owners or operators, who offer their

vessels for hire to carry bulk (dry or liquid) or break bulk (cargoes with individually

handled pieces) to any suitable port(s) in the world, according to a specifically drawn

contract, called a charter party.

Larger cargo ships are generally operated by shipping lines: companies that

specialize in the handling of cargo in general. Smaller vessels, such as coasters, are

often owned by their operators.

Vessel prefixes

A category designation appears before the vessel's name. A few examples of

prefixes for naval ships are "USS" (United States Ship), "HMS" (Her/His Majesty's

Ship), "HMCS" (Her/His majesty's Canadian Ship) and "HTMS" (His Thai Majesty's

Ship), while a few examples for prefixes for merchant ships are "RMS" (Royal Mail

Ship, usually a passenger liner), "MV" (Motor Vessel, powered by Diesel), "MT"

(Motor Tanker, powered vessel carrying liquids only) "FV" Fishing Vessel and "SS"

(Steam Ship, now seldom seen, powered by steam). "TS", sometimes found in first

position before a merchant ship's prefix, denotes that it is a Turbine Steamer. (For

further discussion, see Ship prefixes.)

Famous cargo ships

Famous cargo ships include the Liberty ships of World War II, partly based on

a British design. Liberty ship sections were prefabricated in locations across the USA

and then assembled by shipbuilders in an average of six weeks, with the record being

just over four days. These ships allowed the Allies to replace sunken cargo vessels at

a rate greater than the Kriegsmarine's U-boats could sink them, and contributed significantly to the war effort, the delivery of supplies, and eventual victory over the Axis powers.

Lake freighters built for the Great Lakes in North America differ in design

from "salties" because of the difference in wave size and frequency in the lakes. A

number of these boats are so large that they cannot leave the lakes because they do

not fit into the locks on the Saint Lawrence Seaway.

2.7 Text 7:Sizes of cargo ships

Cargo ships are categorized partly by capacity, partly by weight, and partly by

dimensions (often with reference to the various canals and canal locks they fit

through). Common categories include:

Dry Cargo

Small Handy size, carriers of 20,000 long tons deadweight (DWT)-28,000

DWT

Handy size, carriers of 28,000–40,000 DWT

Seawaymax, the largest size that can traverse the St Lawrence Seaway

Handymax, carriers of 40,000–50,000 DWT

Panamax, the largest size that can traverse the Panama Canal (generally: vessels with a width smaller than 32.2 m)

Capesize, vessels larger than Panamax and Post-Panamax, and must traverse

the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn to travel between oceans

Chinamax, carriers of 380,000-400,000 DWT with main dimensions limited by

port infrastructure in China

Wet Cargo

Aframax, oil tankers between 75,000 and 115,000 DWT. This is the largest

size defined by the average freight rate assessment (AFRA) scheme.

Suezmax, the largest size that can traverse the Suez Canal

VLCC (Very Large Crude Carrier), supertankers between 150,000 and 320,000

DWT.

Malaccamax, the largest size that can traverse the Strait of Malacca

ULCC (Ultra Large Crude Carrier), enormous supertankers between 320,000

and 550,000 DWT

Due to its low cost, most large cargo vessels are powered by bunker fuel which

contains higher sulphur levels than diesel.[4] This level of pollution is accelerating:

with bunker fuel consumption at 278 million tonnes per year in 2001, it is projected

to be at 500 million tonnes per year in 2020.[5] International standards to dramatically

reduce sulphur content in marine fuels and nitrogen oxide emissions have been put in

place.The overall impact of ship emissions depends on the balance of cooling and

warming effects. • NOx emissions lead to increased ozone in the lower atmosphere

(warming) and oxidation of methane (cooling). • Sulphate and organic carbon aerosols (nuclei mode hydrocarbon particulates) scatter solar radiation (cooling). • Sulphates also increase cloud reflectivity (albedo) (cooling). • Black carbon absorbs radiation (warming). • Black carbon on snow is important (warming) and needs further

assessment. [6]If enforced, the International Maritime Organization's marine fuel requirement will mean a 90% reduction in sulphur oxide emissions;[7] whilst the European Union is planning stricter controls on emissions.

2.8 ASSIGNMENTS AND TASKS

I. Read text 3. Prepare excellent reading of this text.

II. Match the definitions to the correct items.

1. hull

2. stern

3. fantail

4. sternpost

5. waterline

6. freeboard

7. shell plating

a. the part between the water and the weather deck.

b. where the side of a ship meets the water

c. the front of a ship extending from the keel.

d. A metal piece covering a ship’s frame

e. the rear of a ship extending from the keel.

f. the sides, bottom and deck of a ship.

g. a curved overhang on a ship’s rear.

II. Place each of the terms below under the correct heading.

Forecastle

Propeller

Keel

Superstructure

Screw

Bulwark

Weather deck

Mast

LOWER SHIP

MIDDLE SHIP

UPPER SHIP

III. Read text 4 and translate it. Retell it.

IV. Complete the sentences with the terms below.

Deck

Hatch

Head

Ladder

Watertight door

Platform

1.Climb up the ______to the main deck.

2. We repaired the ______ in the floor of the third level.

3. The________ is closed because a valve is broken and waste cannot be removed.

4. Damage to the hull caused a lower _______ to flood.

5. Navigators work from the _______because it is higher than most of the ship.

6. A ______ seals a bulkhead.

III. Read text 4 again. What is the difference between a hatch and a door?

IV. Read and translate text 5. Write down new words and expressions from the

text and learn them.

V. Answer the following questions:

1. What types are all cargo ships divided into?

2. What are advantages/disadvantages of specialized vessels?

3. Do you believe that specialized ships will increase in number in future?

Why do you think so?

4. What are special purpose ships?

VI. Read and translate text 6. Speak about the history of cargo ships.

VII. Give the definition of a merchant vessel.

VIII. Name some of the prefixes used to describe a cargo ship.

IX. Learn the following dialogue by heart. Act it out.

There’s a huge ship coming in. She must be a mile long. I think she’s a supertanker.

Yes, she’s one of the big Shell supertankers.

She’s very low in the water.

You’d float low in the water if you had two hundred thousand tons of crude

oil in you.

But I wouldn’t swim at sixteen knots, would I? The tanker is being pulled

along by two tugs, and there are two others at the stern.

I don’t suppose the tugs are actually pulling her through the water just yet.

Out there in the fairway their main job is to help the ship round the bends, and to act

as brakes if the tanker has to stop in a hurry. They’ll start actually pushing and pulling her once she gets close to her berth at the oil terminal.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Китаевич, Б.Е. Морские грузовые операции. Пособие по английскому

языку./ Б.Е. Китаевич, А.И. Кроленко, М.Я. Калиновская, – М.: Высш. шк.,

1991. – 160с.

2. Bardi, E., Coyle, J., Novack R. Management of Transportation. London:

Thomson South-Western. –2006. p.106.

3. Chopra, S., Meindl, P. Supply Chain Management. London: Pearson. –

2007. – p. 300.

4. Christopher, P. Cooper; Shepherd, R. Tourism: Principles and Practice. Financial Times Prent. Int.– 1998. – p.67.

5. D’Acunto, E. Flash on English for Transport and Logistics.—Recanati:

ESP,, 2012. – p.48.

6. Hill, A. Holiday Explorer 1. – Andover: Heinle Cengage Learning, 2012. –

p.63.

7. Hill, A. Holiday Explorer 2. – Andover: Heinle Cengage Learning, 2012. –

p.64.

8. Lay, Maxwell, G.Ways of the World: A History of the World's Roads and of

the Vehicles that Used Them. Rutgers University Press. – 1998. – p. 56.

9. Stopford, M. Maritime Economics. London: Routledge. – 2012. – p.87.

10. Taylor, J., Goodwell, J. Navy. Newsbury: Express Publishing, 2013. –

p.367.

11. Taylor J., Zeter J. Business English. Books 1-3. /J. Taylor, J. Zeter - Newbury: Express Publishing, 2011. – 117p.

12. Taylor J., Zeter J. Business English. Teacher’s Book. /J. Tailor, J. Zeter -Newbury: Express Publishing, 2011. – 38p.

13. Waring R., Editor S. National Geographics Footprint Reading Library Set.

1000 Headwords. Pre-Intermediate Level. / R. Waring, S. Editor. – London: Heinle,

2010.

14. Waring R., Editor S. National Geographics Footprint Reading Library Set.

1300 Headwords. Pre-Intermediate Level. / R. Waring, S. Editor. – London: Heinle,

2010.

15. Waring R., Editor S. National Geographics Footprint Reading Library Set.

2200 Headwords. Pre-Intermediate Level. / R. Waring, S. Editor. – London: Heinle,

2010.