Best Efforts Provisions - Association of Corporate Counsel

advertisement

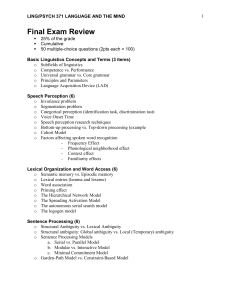

Sixth Annual In-House Counsel Conference Panel 1 Contracts – Is that a Contract, or are You Just Trying to Confuse Me? Presenters Mike Bartyczak, Senior Counsel, Smile Brands Inc. Kresimir Peharda Florence Pinigis, Senior Attorney, Southern California Edison Company Cherie S. Raidy, Partner, Foley & Lardner LLP Moderator – Steven Mashal, IP Attorney 2 Overview Best Efforts Provisions Ambiguity in Contracts Miscellaneous Contract Provisions 3 Best Efforts Provisions: Pitfalls and Practice Pointers Kresimir Peharda 4 Introduction Attorneys believe the meaning of best efforts is clear. Case law says otherwise. Parties who carelessly use "best efforts" provisions run the risk of injecting a significant amount of uncertainty into their contracts. This situation can lead to many problems relating to the performance required of the promisor. 5 Best Efforts Provisions Some iterations of best efforts: good-faith efforts diligent efforts commercially reasonable and diligent efforts reasonable efforts every effort reasonable best efforts good-faith best efforts commercially reasonable efforts commercially reasonable best efforts 6 Best Efforts Provisions Where do best efforts provisions fit within the contract problem universe? Ambiguity Inconsistency Conflict Vagueness Best Efforts Redundancy Imprecision 7 Evaluating Best Efforts Provisions Approaches courts have used to evaluate the term: 1. Let the trier of fact/jury decide (See First National Bank of Lake Park v Gay, 694 So. 2d 784 (Fla. 4th D.C.A. 1997)). 2. Impose a mere good faith standard, or if there is no mutuality of obligation, then decide that there is no legal obligation (adopted by Illinois courts). 3. Impose a greater than good-faith, but less than fiduciary duty standard (See Bloor v. Falstaff Brewing Corp., 601 F.2d 609 (2d Cir. 1979)). 8 Problems Specific problems encountered 1. 2. 3. 4. Unanticipated peer/industry comparisons Heightened trial risks and expenses Conflicts of interest Restrictions on one’s own business opportunities 9 Problems Unanticipated peer/industry comparisons Example: Carlson Dist. Co. v. Salt Lake Brewing Co., L.C., 95 P.3d 1171 (Utah App. 2004) The parties entered into a distribution agreement whereby Carlson was obligated to use its best efforts in the sale, marketing, and distribution of Salt Lake’s beer The Court held that best efforts is primarily a subjective standard, but the actions and capabilities of others may be relevant 10 Problems Conflicts of interest Example: Bloor v. Falstaff Brewing Corp Falstaff (buyer) was required to use its best efforts to promote and maintain a high volume of Ballantine beer sales The Court held that while Falstaff was not required to spend itself into bankruptcy promoting the beer, Falstaff could not focus on profit exclusively without giving fair consideration to the effect on the volume of Ballantine beer sales 11 Practice Pointers Carefully evaluate all contracts using "best efforts" language to determine the potential effects of the inherent vagueness/ambiguity for your client. Define the term once in the agreement and use that definition throughout. If, however, you use two or more standards in an agreement, make sure that it is intentional and that the different standards are defined. 12 Practice Pointers If the promisor’s level of effort is important, consider inserting a benchmark against which the promisor’s effort can be evaluated: Efforts used by the promisor in connection with other contracts imposing an efforts standard How the promisor would have acted if the promisor and promisee were united in the same entity Industry practice Specific industry peers or companies meeting similar financial metrics 13 Practice Pointers If for some reason you choose not to define the efforts term and you need a middle ground, consider using reasonable efforts. Recognize that agreements in the following areas will often raise the effort issue: Securities offerings Distribution and marketing Licensing and franchising Mergers and acquisitions Real estate leases 14 Ambiguity Florence Pinigis Michael A. Bartyczak 15 Overview Part 1: What is ambiguity? Part 2: What are the consequences of a contract provision being considered ambiguous? Part 3: How can you avoid ambiguity? 16 Part 1: What is ambiguity? Not usually the focus of attention---instead, focus of attention is on the effects of ambiguity As a result, contract litigation may center on whether a provision should be viewed as “ambiguous” or “unambiguous” 17 What is ambiguity? A basic definition that may be useful: “ambiguity” is an uncertainty of meaning where an expression is used in a written instrument. Ambiguity may result from language that has two meanings or where the meaning is not clear or definite. 18 What is ambiguity? Is there any practical way that can help to determine if specific language is likely to be considered ambiguous? Try this two part test: Is the language capable of two or more conflicting interpretations, each of which would be considered a reasonable interpretation of the language? Does the language lack a critical term? 19 Identifying Conflicting Interpretations Conflicting interpretations usually arise in two ways: The contract doesn’t sufficiently define a key term Classic Example: the so-called Peerless case, where the contract provided for the purchase of cotton from the ship Peerless for a set price. But there were two ships named Peerless (that sailed from Bombay with cotton a few months apart) so contract was held to be nonbinding. The contract contains conflicting provisions Words and numbers describing the purchase price are different Legal description and address for property differ 20 Identifying Missing Terms The absence of a critical term can render a contract ambiguous when it creates confusion about a party’s rights under the contract Examples of critical terms: price, time for performance or subject matter of the contract. 21 Classifying Ambiguity Ambiguity is often classified based on how the ambiguity is identified: Does the ambiguity arise from the face of the contract or is it only identified as a result of extrinsic evidence? “Patent” ambiguity---arises on the face of the contract (such as where the words and numbers to establish the contract price differ) “Latent” ambiguity---occurs when language that appears to be unambiguous on its face is shown by extrinsic evidence to be ambiguous 22 Part 2: Effect of ambiguity Ambiguity is usually the basis for disputes between parties to a contract. When the dispute gets into litigation, it is generally first considered to be a question of law for the trial court. But where the contract itself is not well defined, however, a court may hear parol evidence to determine what the parties intended to include as a part of the contract. 23 Treatment of Missing Terms As noted above, if a missing term is considered absolutely essential to the contract, then the absence of such a term can nullify the contract. In other cases, a court will attempt to supply a term that is reasonable under the circumstances. In order to supply a missing term, a court will usually look first at the contract itself (applying Rules of Construction, as necessary). 24 Treatment of Missing Terms (cont.) But if the intent of the parties cannot be determined in this way, then a court may look at parol evidence to supply the missing term. Where there is a clear integration clause, however, parol evidence is usually not allowed to supply the missing term (Restatement Section 204) 25 Treatment of Conflicting Terms The Restatement of Contracts does not provide clear direction when an ambiguity arises from conflicting terms. A court may look at contract construction or at parol evidence, but will not usually look at parol evidence where there is an integration clause 26 Part 3: Ways to avoid ambiguity Patent ambiguity may be avoided by consistency in the use of terms where the same meaning is intended. This can be made easier by the use of definitions and rules of interpretation. Latent ambiguity may be avoided by an integrated agreement with an integration clause. 27 Addressing Patent Ambiguity Consistency is one of the keys to avoiding conflicting language within the contract itself. Defining terms and then using them in the way that they have been defined is important. Also may be useful to set forth rules of interpretation within the contract itself. 28 Definition of Terms May be defined in a single location or when each term is first used in the contract With longer contracts, if terms are defined when they are first used then a list of the term and the sections where the definition can be found is useful. Review the terms to identify which terms are related and attempt to eliminate any overlap between them Consider whether undefined terms (usually technical terms) should be interpreted in accordance with the meaning given to such term in a specified industry or whether the ordinary 29 meaning should be used. Creating Rules of Interpretation Rules of interpretation can be used to supplement definitions by explaining how words are being used in the contract. Rules of interpretation can also establish an order of priority among provisions within the contract and among the contract terms and language that may be included in exhibits, appendices or attachments to the contract that are incorporated by reference into the contract. 30 Supplementing Definitions by Rules Examples Use of the word “includes” means “including without limit” Gender of all words include the masculine, feminine and neuter, and the number of all words include the singular and plural. The terms “hereof,” “herein,” “hereto” and similar words refer to the entire contract and not to any specific subpart of the contract. References to any law, statute, rule, regulation, notification or statutory provision shall be construed as a reference to the same as it may have been, or may from time to time be, amended, modified or re-enacted. 31 Supplementing Definitions by Rules Examples (cont.) References to any person shall be construed as a reference to such person’s successors and permitted assigns. Any reference to the “reasonable judgment”, “reasonable consent”, or “reasonable approval”, or to any words of similar effect, shall be interpreted to be subject to the requirement that such judgment, approval, or consent (a) not be unreasonably withheld or delayed, and (b) be in accord with any applicable standards associated with the exercise of such judgment, consent or approval, unless specifically stated to the contrary. 32 Establishing Which Provisions Govern by a Rule Examples (cont.) Headings are for convenience only and are not to be used for interpretation. A reference to this contract or to a part of this contract shall include any authorized amendments, modifications, supplements, replacements or restatements thereto. In case of conflict, the order of precedence for interpretation between the parts of this contract shall be: [usually body of contract over appendices, but not always]. And any amendment to the above listed documents shall have priority over the document it amends, and any amended document shall have the same precedence classification as set forth above. 33 Establishing Which Provisions Govern by a Rule Examples (cont.) In the event of a conflict (a) among, or within, any provisions within any one of the levels set forth in the foregoing order of precedence, and/or (b) among laws and standards identified as applicable to this contract, then the party identifying such a conflict shall notify the other party and the parties, within a reasonable time thereafter, will agree on an interpretation. Until such an interpretation is agreed upon, the assumption will be that the more stringent requirement applies. 34 Addressing Latent Ambiguity As discussed, latent ambiguity is identified by reference to extrinsic evidence. As a result, latent ambiguity can be addressed by provisions in the contract that expressly exclude parol evidence. Typically, an integration clause is used for this purpose. A valid integration clause will bar the use of extrinsic oral or written evidence of prior or contemporaneous agreements to add to or modify the contract. (see Materson v. Sine, 68 Cal.2d 222 (1968)) 35 What Is an Integration Clause? An integration clause states the parties intent that the contract itself be treated as the agreement between the parties. Typical parts: Identification of what comprises the “contract” Statement that the parties intend the contract to be treated as final and complete Statement that prior or contemporaneous written or oral statements are not a part of the contract Statement that no reliance is being made on other representations 36 Effect of an Integration Clause In the absence of an allegation of fraud in the inducement, an integration clause is likely to bar the introduction of extrinsic evidence and thereby will prevent a finding of a latent ambiguity under the contract. But claims related to fraud in the inducement may justify use of extrinsic evidence to nullify a contract, even when the contract has an integration clause, unless the allegedly false promise directly contradicts the written language. 37 Effect of an Integration Clause If the contract is silent on an alleged false promise, then the integration clause will not prevent the introduction of extrinsic evidence where fraud is alleged. So, in addition to an integration clause, you also need to address key terms in the contract (or the integration clause may not have its desired effect). 38 Responding to a Draft Integration Clause Many “take-it or leave-it” contracts include an integration clause Where you feel pressure to sign a contract with this language, consider incorporating helpful appendices into the definition of the contract. Where such appendices contain language that differs from the language in the contract itself, consider including an order of priority provision 39 Ways to Exclude Extrinsic Evidence Sometimes a contract will not include an integration clause but excludes certain types of extrinsic evidence, such as past practice or course of dealing. Typically, this is done when there is a long relationship between the parties and the new contract has modified the past relationship in a significant way. A provision excluding past practices or courses of dealing can prevent a party from showing that what was actually done under the contract should govern over the contract 40 language. Miscellaneous Contract Provisions Cherie S. Raidy 41 QUESTIONS? 42 Contact Information Michael A. Bartyczak, Smile Brands Inc. mike.bartyczak@brightnow.com Kresimir Peharda (626) 230-7422, kresimir@adriapacific.com Florence Pinigis, Southern California Edison Company (626) 302-3959, florence.pinigis@sce.com Cherie S. Raidy, Foley & Lardner, LLP (213) 972-4554, craidy@foley.com 43