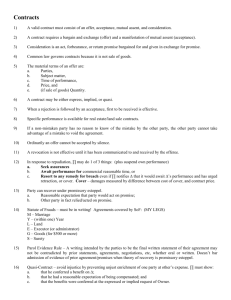

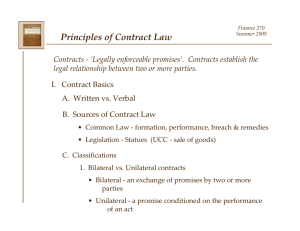

Chapter 2: Damages for Breach of Contract

advertisement