Slide 1

advertisement

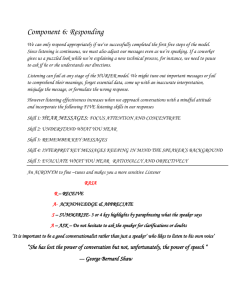

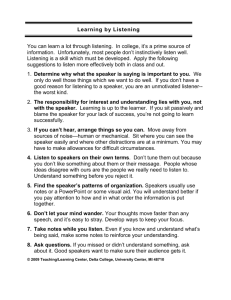

Lecture 41 Listening and Interviewing In this lecture we will learn to • Apply the communication process to oral communication • Summarize the skills involved in being an effective listener • Identify nine common types of business interviews Facing a communication dilemma at Rockport • • • • • • • • • • Calling a meeting isn’t unusual; executives do it every day. Even so, few executives shut down an entire company to bring everyone to a meeting, but that’s exactly what Rockport president John Thorbeck decided to do. Rockport is a footwear subsidiary of Reebok, and except for the handful of people left behind to answer telephones in the company’s headquarters, all 350 managers and employees were asked to gather in a huge room for a two-day meeting. Many of Thorbeck’s top managers questioned the need for halting the daily functions, complaining that a company as large as Rockport could not afford to lose two whole shipping days. But Thorbeck believed this meeting was important enough to involve every employee at every level. His objective was nothing less than to increase the company’s potential. If you were John Thorbeck, how would you use a two-day meeting to elicit input from your employees? What factors of oral communication would you use to get them talking? Would good listening skills be valuable? What would you do to be sure the meeting was productive? Communicating Orally • • • Rockport’s John Thorbeck knows that speaking and listening are the communication skills we use the most. Given a choice, people would rather talk to each other than write to each other. Talking takes less time and needs no composing, typing, rewriting, retyping, duplicating, or distributing. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • More important, oral communicating provides the opportunity for feedback. When people communicate orally, they can ask questions and test their understanding of the message; they can share ideas and work together to solve problems. They can also convey and absorb nonverbal information, which reveals far more than words alone. By communicating with facial expressions, eye contact, tone of voice, gestures and posture, people can send subtle messages that add another dimension to the spoken words. Oral communication satisfies people’s need to be part of the human community and makes them feel good. Talking things over helps people in organizations build morale and establish a group identity. Nonetheless, oral communication also has its dangers. Under most circumstances, oral communication occurs spontaneously, you can’t cross out what you just aid and start over. Your most foolish comments will be etched in the other person’s memory, regardless of how much to try to explain that you really meant something else entirely. Moreover, if you let your attention wander while someone else is speaking, you miss the point. You either have to muddle along without knowing what the other person said or admit you were daydreaming and ask the person to repeat the comment. One other problem is that oral communication is too personal. People tend to confuse your message with you as an individual. They’re likely to judge the content of what you say by your appearance and delivery style. Intercultural barriers can be as much a problem in oral communication as they can be in written communication. As always, it’s best to know your audience, including any cultural differences they may have. Your message should always be communicated in the tone, manner, and situation your audience will feel most comfortable with. Whether you’re using the telephone, engaging in a quick conversation with a colleague, participating in a formal interview, or attending a meeting, oral communication is the vehicle you use to get your message across. • When communicating orally, try to take advantage of the positive characteristics while minimizing the dangers. • To achieve that goal, work on improving two key skills: – – Speaking Listening. Speaking • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Because speaking is such an ingrained activity, we tend to do it without much thought, but that casual approach can be a problem in business. Be more aware of using speech as a tool for accomplishing your objectives in a business context. To do this, break the habit of talking spontaneously, without planning what you’re going to say or how you’re going to say it. Learn to manage the impression you create by consciously tailoring your remarks and delivery style to suit the situation. Become as aware of the consequences of what you say as you are of the consequences of what you write. With a little effort, you can learn to apply the composition process to oral communication. Before you speak, think about your purpose, your main idea, and your audience. Organize your thoughts in a logical way, decide on a style that suits the occasion, and edit your remarks mentally. As you speak, watch the other person, judging from verbal and nonverbal feedback whether your message is making the desired impression. If not, revise and try again. Just as various writing assignments call for different writing styles, various situations call for different speaking styles. Your speaking style depends on the level of intimacy between you and the other person and on the nature of your conversation. When you’re talking with a friend, you naturally speak more frankly than when you’re talking to your boss or a stranger. When you’re talking about a serious subject you use a serious tone. As you think about which speaking style is appropriate, think too about the nonverbal message you want to convey. People derive less meaning from your words than they do from your facial expressions, vocal characteristics, and body language. The nonverbal message should reinforce your words. Perhaps the most important thing you can do to project yourself more effectively is to remember the “you” attitude, earning other people’s attention and goodwill by focusing on them. For example, professionals like Rockport’s John Thorbeck elicit opinions from others not only by asking them pointed questions but also by paying attention to their responses. An important tool of oral communication, the telephone, can extend your reach across town and around the world. However if your telephone skills are lacking, you may waste valuable time and appear rude. You can minimize your time on the telephone while raising your phone productivity by delivering one-way information by fax. • Other ways of increasing your phone productivity by – – – – – jotting down an agenda before making a call saving social chitchat for the end of a call saving up all the short calls you need to make to one person during a given day and simply making one longer call sending your message by fax, if you cant reach someone by the phone making sure you’re your assistant has a list of people whose calls you’ll accept even if you’re in a meeting. Listening • • If you’re typical, you spend over half your communication time listening. Listening supports effective relationships within the organization, enhances the organization’s delivery of products, alerts the organization to the innovations growing from both internal and external forces, and allows the organization to manage the growing diversity both in the workface and in the customers it serves. • An individual with good listening ability is more likely to succeed; good listening enhances performance, leading to raises, promotions, status, and power. • However, no one is born with the ability to listen; the skill is learned and employed through practice. • Most of us like to think of ourselves as being good listeners, but the average person remembers only about half of what’s said during a 10 minute conversation and forgets the other half within 48 hours. What happens when you listen • Sensing – – – • Interpreting – Interpreting is decoding and absorbing what you hear. – As you listen, you assign meaning to the words according to your own values, beliefs, ideas, expectations, roles, needs and personal history. The speaker’s frame of reference may be quite different, so the listener may need to determine what the speaker really means. Increase the accuracy of your interpretation by paying attention to nonverbal cues. – – • Sensing is physically hearing the message and taking note of it. This reception can be blocked by interfering noises, impaired hearing, or inattention. Tune out distractions by focusing on the message. Evaluating – – – Evaluating is forming an opinion about the message. Sorting through the speaker’s remarks, separating fact from opinion, and evaluating the quality of the evidence require a good deal of effort, particularly if the subject is complex or emotionally charged. Avoid the temptations to dismiss ideas offered by people who are unattractive or abrasive and to embrace ideas offered by people who are charismatic speakers. • Remembering – – • Responding – – – – • Remembering is storing a message for future reference. As you listen, retain what you hear by taking notes or making a mental outline of the speaker’s key points. Responding is acknowledging the message by reacting to the speaker in some fashion. If you’re communicating one on one or in a small group, the initial response generally takes the form of verbal feedback. If you’re one of many in an audience, you ay act on what you have heard. Actively provide feedback to help the speaker refine the message. Listening requires a mix of physical and mental activities and is subject to a mix of physical and mental barriers. The three types of listening • • • • • Various situations call for different listening skills. The three types of listening differ not only in purpose but also in the amount of feedback or interaction that occurs. The goal of content listening is to understand and retain information imparted by a speaker. You may ask questions, but basically information flows form the speaker to you. Your job is to identify the key points for the message, so be sure to listen for clues to its structure: – – – – • • • • Previews Transitions Summaries Enumerated points In your mind create an outline of the speaker’s remarks; afterward, silently review that you’ve learned. You may take notes, but you do this sparingly so that you can concentrate on the key points. It doesn’t matter whether you agree or disagree, approve or disapprove – only that you understand. The goal of critical listening The three types of listening is to evaluate the message at several levels: – – – – – – The logic of the argument Strength of the evidence Validity of the conclusions The implications of the message for you or your organization The speaker’s intentions and motives The omission of any important or relevant points • • • • • • • • • Because absorbing information and evaluating it at the same time is hard, reserve judgment until the speaker has finished. Critical listening generally involves interaction as you try to uncover the speaker’s point of view. You are bound to evaluate the speaker’s credibility as well. The goal of active or emphatic listening is to understand the speaker’s feelings, needs, and wants so that you can appreciate his or her point of view, regardless of whether you share that perspective. By listening in an active or emphatic way, you help the individual vent the emotions that prevent a dispassionate approach to the subject. Avoid the temptation to give advice. Try not to judge the individual’s feelings. Just let the other person talk. All three types of listening can be useful in work-related situations, so it pays to learn how to apply them. How to be a better listener • • Regardless of whether the situation calls for content, critical, or active listening, you can improve your listening ability by becoming more aware of the habits that distinguish good listeners from bad. In addition, put nonverbal skills to work as you listen: – Maintain eye contact – React responsively with head nods or spoken signals – Pay attention to the speaker’s body language • You might even test yourself from time to time: when someone is talking, ask yourself whether you’re actually listening to the speaker or mentally rehearsing how you’ll respond. • Above all, try to be open to the information that will lead to higher-quality decisions, and try to accept the feeling that will build understanding and mutual respect. • If you do, you’ll be well on the way to becoming a good listener – an important quality when conducting business interviews. Good and bad listening To listen effectively The Bad Listener The Good Listener 1. Find areas of interest Tunes out dry subjects Opportunizes; ask “What’s in it for me” 2. Judge content, not delivery Tunes out if delivery is poor Judges content; skips over delivery error 3. Hold your fire Tends to enter into argument Doesn’t judge until comprehension is complete; interrupts only to clarify 4. Listen for ideas Listens for facts Listens for central themes 5. Be flexible Takes extensive notes using only one system Takes fewer notes; uses four to five different systems, depending on the speaker. To listen effectively The Bad Listener The Good Listener 6. Work at listening Shows no energy output; fakes attention Works hard; exhibits active body state 7. Resist distractions Is distracted easily Fights or avoids distractions; tolerates bad habits; knows how to concentrate 8. Exercise your mind Resists difficult expository material; seeks light, recreational material Uses heavier material as exercise for the mind 9. Keep your mind open Reacts to emotional words Interprets emotional words; does not get hung up on them 10. Capitalize on the fact that thought is faster than speech Tends to daydream with slow speakers Challenges, anticipates, mentally summarizes Conducting interviews on the job • • • Your speaking and listening skills will serve you throughout your career. For example, from the day you apply for your first job until the day you retire, you’ll be involved in a wide variety of business interviews. These interviews are actually planned conversations with a predetermined purpose that involve asking and answering questions. • In a typical interview the action is controlled by the interviewer, the person who schedule the session. • This individual poses a series of questions, designed to elicit information from the interviewee. • Interviews sometimes involve several sometimes involve several interviewers or several interviewees, but more often only two people participate. • The conversation bounces back and forth from interviewer to interviewee. Although the interviewer guides the conversation, the interviewee may also seek to accomplish a purpose, perhaps to : • – – – – obtain or provide information, solve a problem to create goodwill persuade the other person to take action. • • If the participants establish rapport and stick to the subject at hand, both parties have a chance of achieving their objective. To help you understand interviews on the job, we will discuss how interviews are categorized, how you can plan for them, what sorts of questions you can use, and how you can structure them. Categorizing interviews • • • The interviewer establishes the style and structure of the session, depending on the purpose of the interview and relationship between the parties, much as a writer varies the style and structure of a written message to suit the situation. Each situation calls for a slightly different approach, as you can imagine when you try to picture yourself conducting some of these common business interviews. Job interviews – – – • Information interviews – – • The interviewer seeks facts that bear on a decision or contribute to basic understanding. Information flows mainly in one direction: one person asks a list of questions that must be covered and listens to the answers supplied by the other person. Persuasive interviews – – – – • The job candidate wants to learn about the position and the organization; the employer wants to learn about the applicant’s abilities and experience. Both hope to make a good impression and to establish rapport. Initial job interviews are usually fairly formal and structured, but later interviews may be relatively spontaneously as the interviewer explores the candidates responses. One person tells another about a new idea, product, or service and explains why the other should act on the recommendation. Persuasive interviews are often associated with, but are certainly not limited to, selling. The persuader asks about the other person’s needs and shows how the product or concept is able to meet those needs. Persuasive interviews require skill in drawing out and listening to others as well as the ability to impart information. Exit interview – – – – The interviewer tries to understand why the interviewee is leaving the organization or transferring to another department or division. A department employee can often provide insight into whether the business is being handled efficiently or whether things could be improved. The interviewer tends to ask all the questions while the interviewee provides answers. Encouraging the employee to focus on events and processes rather than on personal grips will elicit more useful information for the organization. • Evaluation interview – – – • A supervisor periodically gives an employee feedback on his or her performance. The supervisor and the employee discuss progress toward predetermined standards or goals and evaluate areas that require improvement. They may also discuss goals for the coming year, as well as the employee’s long-term aspirations and general concerns. Counseling interviews – – – – • A supervisor talks with an employee about personal problems that are interfering with work performance. The interviewer is concerned with the welfare of both the employee and the organization. The goal is to establish the facts, convey the company’s concern, and steer the person toward a source of help. Only a trained professional should offer advice on such problems as substance abuse, marital tension, and financial trouble. Conflict-resolution interviews – – – • Two competing people or groups of people explore their problems and attitudes. For example Smith versus Jones, day shift versus night shift, General Motors versus the United Auto Workers. The goal is to bring the two parties closer together, cause adjustments in perceptions and attitudes and create a more productive climate. Disciplinary interviews – – – – • A supervisor tries to correct the behavior of an employee who has ignored the organization’s rules and regulations. The interviewer tries to get the employee to see the reason for the rules and to agree to comply. The interviewer also reviews the facts and explores the person’s attitude. Because of the emotional reaction that is likely, neutral observations are more effective than critical comments. Termination interviews – – – A supervisor inform an employee of the reason for the termination The interviewer tries to avoid involving the company in legal action and tries to maintain as positive a relationship as possible with the interviewee. To accomplish these goals, the interviewer gives reasons that are specific, accurate, and verifiable. In this lecture we learnt to • • • Apply the communication process to oral communication Summarize the skills involved in being an effective listener Identify nine common types of business interviews