Slides, draft (PowerPoint)

advertisement

1

COLANG2014

Institute on Collaborative Language Research

Orthography Development:

The ‘Midwife’Approach

Mike Cahill

Colleen Fitzgerald

Keren Rice

Gwen Hyslop

Kristine Stenzel

Contents of Power Point

• Introductory discussion (slides 5-9)

• Introduction to ‘Midwife’ approach (slides 10-28)

• Overview of linguistic issues (slide 29)

• Dealing with allophones (slides 30-42)

• Dealing with allomorphs (slides 43-48)

• Suprasegmental problems (slides 49-52)

• “New” sounds: Dene and Kurtöp (slides 53-79)

• Variation and standardization (slides 80-97)

• Review of Methodology (slides 98-101)

• Further issues (102-119)

• A final political example (120-129)

• Summary (slides 130-131)

• References/Contact info (slides 132-133)

2

Some background

• These slides were developed for a course at InField,

taught in 2008 by Keren Rice and Kristine Stenzel, in

2010 by Gwen Hyslop and Keren Rice, in 2012 by

Colleen Fitzgerald and Keren Rice, and now in 2014

by Keren Rice and Mike Cahill.

• All have first-hand experience in orthography

development (detailed at the end of this presentation).

3

Our Goals:

Discuss important questions and parameters

(socio-political, technical-linguistic, psychocognitive) related to orthography development

2. Consider an approach to orthography

development (o.d.) based on community

involvement, writing practice, and analysis

3. Provide opportunities for hands-on analysis

4. Exchange experiences, brainstorm, expand

resources

4

1.

Initial Discussion Questions

• What is an orthography?

• How would you define the role of the linguist in

the process of orthography development?

• What do you think a language community expects

from the linguist and from the orthography

development process in general?

• What are the features of a ‘good’ orthography and

what kinds of things do we need to know in order

to develop one?

5

What is an orthography? Some

thoughts for discussion

• Agreed upon system to represent

sounds/words/concepts of a language

• Practical tool for communication

•…

6

What is the role of the linguist?

• Facilitator

• Mediator

•…

7

What does the community expect

from the linguist?

• Intervention around different spellings and

competing orthographies

• Expertise and connections that are not present

in the community

• Legitimacy of the language

•…

8

What are features of a ‘good’

orthography?

• Easy to learn and to produce

• Minimize number of characters, maximize what

they represent

• Culturally relevant

• Transfer from matrix language

• Visually contrastive

•…

9

The ‘Midwife’ approach

What is it?

10

The ‘midwife’ approach to the

development of an orthography

• overall goal: to approach o.d. as a process

• based on exchange and integration of knowledge and experiences of

linguist and language community (LC)

• with LC as active participant, sharing ‘joint responsibility’ for final

outcome

• methodology: practice of writing and analysis of the language

feed into each other

• linguist’s role:

facilitator/guide in the practice - analysis dialectic

• What kind of practice can help identify and focus the issues so that the

analysis becomes more clear?

• What kinds of appropriate metaphors can be useful tools?

11

Basic principles of the approach

• notion of o.d. as a process whereby members of a

language community (LC) come to analyze aspects of

their own language and develop a new practice: writing

• during the process (which may continue over an extended

period of time), orthographic variation is ok

• continuous and reflective practice (LC writing and

reading) is always the primary input to language-analysis

activities

• LC linguistic knowledge and social interpretations are

also a fundamental input

12

An overview of the ‘midwife’

approach to orthography

development

Getting started 1: Discussion with LC

Getting started 2: Types of writing systems

Getting started 3: Learnability

13

Getting started in developing a

writing system – 1: discussion with the LC

Why do we need to study our own

language in order to think about

writing it?

Discussion:

How are oral language and written

language similar and how are they

different?

14

15

Oral Language

Written Language

•Communication between people in

same place/time (immediate).

Communication between people in

different places/times (extended).

Allows for reductions, use of body

language and abbreviated deictic

references, because misunderstandings /

doubts can be resolved then and there.

Requires more complete forms and

additional symbols to aid understanding –

tools to make sure that the writer’s

message will reach the reader intact.

Is where innovations and change

appear first.

Tends to reflect stable forms, changes more

slowly.

Always includes more types of

variation, which may show different

origins, group affiliations, or contexts

requiring different registers (e.g.

formal/informal).

•May include (or not) variation that

represents differences between groups of

speakers of the same language, especially

during initial phases;

•May be unified (or not) as a result of

process of practice, analysis (discussion of

variations and what they represent), and

political decision-making.

15

Getting started – 2: presentation/discussion

of types of writing systems and the symbols

they use

What do symbols represent in different types of writing

systems?

1. ‘Morphographic’ / ‘Logographic’ representations of

words or morphemes

16

2. ‘Phonographic’ systems: representations

of syllabic combinations

Cree

17

3. ‘Alphabetic’ representations of

individual sounds

The traditional thought in o.d. is that each symbol in an alphabet

should represent a phonological segment, (ideally) corresponding

(as directly as possible) to the phonemes of the language

Consonantal alphabets: symbols represent consonants

Full alphabets: symbols represent consonants and

vowels (e.g. Greek and Latin alphabets)

18

Mayan

make by

friction

he light-fire

Itzamna our God

‘Our God Itzamna made his fire using

friction.’

19

All orthographies change over time

Roman Alphabet (2,600+ years old)

20

Getting started – 3: discussion of

‘Learnability’

Who is the writing system for? Will it be

used primarily by native speakers?

Learners of the language?

What kinds of orthographic features might

help increase ‘learnability’ for each of

these target groups?

21

An important assumption

• There is a writing system to begin from. (For

instance, learners are literate in another language

such as English or Spanish.)

• In such cases, familiarity with an existing system

will probably lead the LC to adopt a similar type

of orthographic representation, but will require

analysis so that they can recognize where

adjustments need to be made.

22

A ‘getting started’ exercise

for the LC

This type of exercise works well in workshoptype situations, and will likely provide activities

for many days of work. It is a good way to get a

large variety of members of the LC involved in

the discussions. If activities are organized in

groups, literate and non-literate individuals and

speakers with varying degrees of fluency can

have input.

23

A. LC participants choose a theme (or

themes) and write short texts

(individually or in groups)

B. Participants exchange texts to

read, making lists of doubts they

encounter or alternative ways to

write specific words

24

C. Participants present their

doubts and suggestions to the

entire group – this is the data

that will guide the analysis

and inform decision-making

25

What kinds of information are likely to be

revealed by this initial exercise?

In terms of orthographic symbols, that:

• Various symbols are being used for the same sound

• No symbol is available for a sound in the language

Both cases may result from the effect of literacy in a different

language or from alternate existing orthographies. Recognition

of where the problems lie is a first step in analysis.

26

27

In terms of phonology:

Sets of examples of important phonological elements

and indications as to their ‘functional loads’

Evidence of allophonic variation

Indication of variation between speakers of different

ages or from different regions

In terms of morphology:

questions as to word boundaries and other morphological

issues such as what to do about compound words or

27

complex constructions

28

Continuing the exercise . . .

D. As the participants present the results of these

activities, the linguist should be able to recognize

and group together the different categories of

‘doubts’ and begin to think about how to work on

them with the LC

E. Subsequent activities should focus on individual

issues, analyzing them with the LC so that informed

decisions can be made collectively

28

29

Linguistic issues: what to do

about . . .

• Allophones

• Allomorphs

• Suprasegmentals

• Sounds in the language that are

not represented in a known writing

system

29

Representing allophones

30

31

Allophones in English

pool

spool

[ph]

[p]

Allophones have the same

representation in the orthography.

31

32

An example of allophones and their

representation in the orthography in o.d.:

Kotiria (Eastern Tukanoan) [d] and [r]

In this language, as onset consonants, these

sounds occur in complementary distribution: [d]

word-initially and [r] word-internally

dukuri ‘manioc roots’

duhire ‘you/he/she/they sat’

diero ‘a dog’

What decision was made in this case?

32

33

Analysis with the LC

a) Participants in the language workshop compiled a list

of words containing the two sounds from their own

written texts

b) All occurrences of the sounds were highlighted, so that

participants could visually observe their distribution

c) Participants were asked if they could think of other

words with different sounds in the positions of [d] and

[r] (in other words, to find minimal pairs), leading to

analysis and recognition of /d/ as a ‘basic sound’

(phoneme) and [r] as a ‘variant’ (allophone)

33

34

d) Once speakers had observed and analyzed for

themselves that [r] was a variant of /d/ in a specific

position, it was possible to discuss whether or not to

represent it with a different symbol

e) Collectively, several of the texts were re-written

using only ‘d’ and speakers were asked to evaluate

how they felt, as writers and readers, about the use of

a single symbol

34

35

Coming to conclusions

f)

While recognizing /d/ as underlying sound, use of the symbol ‘d’

in both positions felt uncomfortable to the participants. They

argued that it contradicted a well-established surface distribution

of sounds, making the written and spoken versions of the

language look too different. Additionally, use of ‘d’ in wordinternal position made the written texts look like they represented

the pronunciation of closely-related languages in the family, in

which the d-r distribution does not occur.

g)

Thus, the LC has opted to use different symbols for the ‘d’ and

‘r’ sounds in the orthography, a decision informed by linguistic

analysis but respectful of input from the LC as the end users of

the system.

35

What if…?

• Kɔnni (Gur, northern Ghana) has a similar

distribution of [d] and [r]:

• dàáŋ

• kʊ́rʊ́bâ

‘stick’

‘bowl’

dígí

chʊ̀rʊ́

• These appear to be allophones of /d/.

‘to cook’

‘husband’

But, some complications:

[d] is intervocalic when it’s

• lexeme-initial (in a compound word)

jùò-dìkkíŋ

‘cooking room’ (cf. digi ‘to

cook’)

• in borrowed words and ideophones

‘banana’ (Twi)

‘dung-beetle’

• Discuss: Does this make a difference?

What other questions would you ask?

kòdú

bìn-dúdù

Factors to check:

• Speakers’ preferences

• Other neighboring languages

• Any other linguistic or psycholinguistic evidence?

•…

• Almost totally illiterate group, not informed enough to

express a preference

• All related languages have both <d> and <r>. Sometimes

separate phonemes, sometimes not.

Also, influence of English.

• And…

A test…

• Other voiced stops lenite intervocalically; couldn’t

/d/ also? Stops occur in careful speech, fricatives in

casual.

• bɔ́bɪ́ ~ bɔ́βɪ́

‘to tie’

• hɔ̀gʊ́ ~ hɔ̀ɣʊ́

‘woman’

• However, Kɔnni speakers can tell the difference in [d]

and [r], and corrected my pronunciation when I

attempted *[hààdɪ́ŋ] rather than [hààrɪ́ŋ]’boat’

• Conclusion: /d/ and /r/ have recently become separate

phonemes, and conforming to other languages, are

written with two symbols.

40

Another Allophone Example

• Choctaw, a Native American language in

Mississippi and Oklahoma has had a number of

orthographies.

• The language has three vowel phonemes:

/i o a/,which can be short, long, or nasalized.

• However, the writing systems often use six

symbols, following how the language was

written in the 19th century, associated with

Cyrus Byington.

40

41

Choctaw Vowels

(from Alphabet links at Choctaw Language School online)

• Two of the allophones of phoneme /a/ get represented in

the writing system. Allophone [a] tends to appear in open

syllables, written as a.

• chaha

'tall'

• taloowa

'sing'

• The other allophone, [ə], tends to appear in short closed

syllables and is written using a symbol not used as a vowel

in English, ν.

• anνmpa

'word, language'

• kνllo

'hard'

41

42

Conclusions from the Choctaw

allophones

• This example using allophones shows that sometimes

the choice is made to write allophones.

• Not all Choctaw vowel allophones are represented

with unique orthographic symbols, but some are.

• We will see some parallels in the upcoming allomorph

examples from English, where some of the variation

can be chosen to be written overtly in the writing

system.

42

43

Questions of allomorphy

43

44

Problems of allomorphy

Shallow vs. deep orthographies

Shallow: close to pronunciation

Deep: preserves graphic identity of

meaningful elements

44

45

English allomorphy

A combination of deep:

cats [s]

dogs [z]

And shallow:

intangible [n] impossible [m]

45

46

Allomorphs: Dene voicing

alternations

sa ‘watch’

xa ‘hair’

shá ‘knot’

Shallow orthography?

(“phonetic”)

Deep orthography?

(“phonemic”)

sezá

seghá

sezhá

‘my watch’

‘my hair’

‘my knot’

sa

sezá

sa

sesá

46

47

The process 1

An orthography standardization

committee was established to make

decisions about the orthography.

A few decisions involved symbols;

most involved spelling conventions.

The committee considered basic

principles – audience, goals of

writing, transfer from English, …

47

48

The process, continued

The committee identified areas of

concern with the different choices.

People experimented with the different

ways of writing words with these

alternations.

Decision: shallow orthography

Why? Easier to figure out from the

pronunciation

48

49

Beyond the segment:

suprasegmental problems

49

50

Nasalization in Tukanoan

languages

In Tukanoan languages, nasalization is a

property of the morpheme rather than of

individual segments, thus it functions as a

suprasegment and the question quickly arises

as to how it should be represented in the

orthography of these languages

50

51

Analysis of nasalization with

the LC:

Finding metaphors to help speakers understand how nasalization

works in different kinds of languages . . .

‘umbrella’ nasalization –

‘covers’ the entire morpheme

(Tukanoan languages)

‘raincoat’ nasalization –

‘covers’ individual segments

(e.g. in Portuguese)

51

52

Some nasalization proposals

Over time, after analyzing and understanding how nasalization

operates in Tukanoan languages, a number of different proposals for

how to mark nasalization were ‘tested’ by participants in language

workshops. In each case, writing and reading exercises using the

different possibilities were proposed, practiced, and then evaluated.

Eventually, it was collectively decided that:

•Morphemes with nasal consonants (m, n, ñ) require no further

marking, the nasal C being sufficient to identify the morpheme as

+nasal

•In morphemes with no nasal C̃, the first vowel is marked with a

tilda: ṽ to indicate the morpheme as +nasal

52

53

‘New’ sounds:

sounds not distinctly represented

in a known writing system

53

54

‘New’ sounds 1: Dene mid front

open and closed vowels

• Early orthography used the symbol {e} for

both an open and closed front vowel.

• Both these vowels exist in some dialects.

54

55

The process

• A question: Should these vowels be

differentiated?

• The answer: yes!

• Why?

•Accurate representation of sounds of the

dialect

•Ease of reading

55

56

The process: What symbol to

use?

• A new symbol is needed.

• The open vowel is more common than the closed

vowel.

• Choice: symbol {e} for the open vowel; schwa

(‘upside down e’) for the closed vowel

• This choice was made because the open vowel is more

common, and it meant fewer changes in how people

were already writing.

• This decision was a surprise for some of the linguists

involved, but people liked it because they knew that

schwa was used in linguistics.

56

57

‘New’ sounds 2: The case of

Kurtöp

• Kurtöp is a Tibeto-Burman language of Bhutan

• About 15,000 speakers

• Speakers who are literate are usually familiar

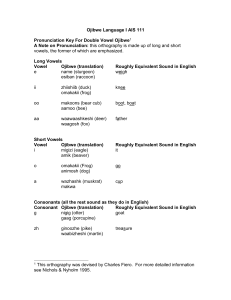

with 1) English and 2) Dzongkha

• Roman orthography was a natural product but

the ’Ucen system was suggested by community

and Dzongkha Development Commission

57

58

Which versions of ‘Ucen?

<tshugs.yig> tshui

<mgyogs.yig> joyi

•We opted to begin with joyi, since it was what children learned

and was purely Bhutanese (as opposed to tshui, which is

shared with Tibetan).

58

59

The ’Ucen syllable

In the Classical Tibetan Orthography,

an abugida derived from Brahmi, and

devised in 632 AD, syllables are

represented according to this diagram.

The “R” represents a simple onset, or

in the case of an onset-less syllable,

the vowel. C1, C2, and C4 may be

used to add consonants to the onset,

making it complex. The V slots are for

vowels (i, e, o go above; u goes

below). C3 represents a single coda (if

present) and C5 makes a complex

coda (rarely occurs).

59

60

The ’Ucen syllable

<bsgrubs>

For example, this is how the Classical

Tibetan word /bsgrubs/ was written. The

complex onset is represented by <b> in

C1 position, <s> in the C2 position, <g>

in the root position, and <r> in the C4

position. The vowel /u/ is represented

below the C4. <b> in C3 and <s> in C5

indicate the complex coda.

60

61

The ’Ucen syllable

Traditionally, there is a fixed number

of symbols available for each slot. C1

may be one of five symbols.; R may be

one of 30; C2 may be one three (one of

which is modified from its occurrence

elsewhere); C3 draws from ten possible

symbols; C4 draws from a set of five

(mainly) ‘half’ symbols; and C5 may

be one of two. The top V may be one

of three vowel diacritics and the lower

V is reserved for one diacritic.

In Joyi, various combinations of C2

with R, or C4 with R, lead to unique

symbols reserved for the exclusive

representation of the combination,

similar to ‘conjucts’ in devanagari.

61

62

’Ucen and Tibetan

• Classical Tibetan phonology had around 28

consonants (labial, dental, palatal velar).

• And complex onsets

• And five vowels

• No tone

• ’Ucen was designed for this phonology

62

63

’Ucen and Tibetan

• However, after almost 1,400 years of change,

Lhasa Tibetan (the prescribed standard) has:

• A new series of retroflex consonants

• Two new vowels (front high and mid rounded)

• High and low tonal registers; level and falling

tonal contours

• Changes in voicing/aspiration contrasts

• Simplified onsets

• Words are NOT pronounced as written!

63

64

’Ucen and Bhutan

• The modern use of ’Ucen assumes the 1400 years of

change from Classical Tibetan to modern Lhasa Tibetan.

• ’Ucen is used this way in Bhutan; for example, words

with complex onsets in Classical Tibetan are still written

as such in modern Tibetan/Dzongkha, but not

pronounced as such.

• Representing any pronunciation using ’Ucen entails the

reader to infer the sound change.

• There is no way to represent various aspects of the

phonology – such as the complex onsets – in the history

of Bhutanese education.

64

65

’Ucen and Tibetan

<bsgrubs>

•For example, the

spelling <bsgrubs> is

pronounced: ɖùp

65

66

’Ucen and Kurtöp

• Kurtöp is not a descendent of Classical Tibetan.

• The phonology of Kurtöp is different from the

phonology of Classical Tibetan or Dzongkha.

• Kurtöp tone, vowel length, and complex onsets

are particularly difficult to represent.

• The following is an illustration of how we

chose to represent complex onsets.

66

67

Kurtöp phonology

Kurtöp complex onsets

67

68

The problem

<pr-> is pronounced as a voiceless retroflex, but

in Kurtöp /pra/ = ‘monkey’

68

69

Midwife process

• So what do you do with the previously

unwritten Kurtöp?

• We presented ideas to a small group of literate

Kurtöp speakers;

• Consulted local teachers

• Consulted highly educated speakers of related

languages with similar phonologies

69

70

Midwife process

Idea 1:

Use ’Ucen in

a way similar

to Roman.

<pra>

But the following problem developed:

How to represent vowels other than /ɑ/?

70

71

Midwife process

This would be confused

with /lé/ in Dzongkha/Tibetan

conventions

<ble>

<bele>

This leads people to tend to pronounce the

word correctly, but does not follow the

traditional conventions and is unattractive.71

72

Midwife process

• In 2009 we organized a workshop with the

Dzongkha Development Commission, Scott

DeLancey, local leaders and interested

community members to address all the issues

72

73

Proposed solution

•We will add ‘half’ letters to be used directly below the root

consonant.

•Based on existing (but rarely used) conventions established

in Tibetan to represent different languages.

•Should not affect Dzongkha transference issues

•Aesthetically pleasing

73

•Kurtöp speakers find it intuitive and easy to read

74

Proposed solution –

not whole slide

• Existing computer fonts do not allow the

needed combinations

• Chris Fynn, DDC font developer, agreed

to adapt the Bhutan ’Ucen fonts (joyi and

tshui) to accommodate the new

combinations

• In addition to the complex onsets, the

adapted fonts will be able to mark tone

74

75

Proposed solution

•Tshui font is finished but

the Joyi font has been held

up indefinitely for

unknown reasons.

•In addition to handling

the ‘new’ complex onsets,

we also have a way (marks

above the other symbols in

top row) to mark tone,

another ‘new’ sound.

75

76

Moving forward (the midwife

process continues)

•The Kurtöp/English/Dzongkha

dictionary is expected to be

published in 2013.

•Kurtöp entries will use the new

font and proposed combinations,

in Joyi if it is made soon, or else

using Tshui.

•Testing will continue…

76

Complex scripts

• SIL’s “Non-Roman Script Initiative” (NRSI) works to develop

computer solutions for complex scripts.

(http://scripts.sil.org/cms/scripts/page.php?item_id=Welcome)

Also see scriptsource.org for a participative site.

78

What have we seen – and not

• Linguistically, we looked at orthography choices with

respect to the implications of representing:

• allomorphs, allophones, suprasegmentals, and sounds in the

language that are not represented in a known writing system

• With sounds that are not represented in a known

writing system, different choices might be made, with

different pros and cons to each choice.

• Let's consider Choctaw, which has a voiceless lateral,

IPA symbol /ɬ/.

78

79

Considering implications of symbol

choice and the language's phonology

• Using IPA:

• Pro: linguistic representation, new representation for unfamiliar sound

• Con: font, no transference

• Adapt English symbols:

• Pro: familiar symbols

• Con: symbols used in unfamiliar ways

• We could imagine lh and hl. Choctaw uses both, in different

environments.

• lh (pνlhki 'fast') before a consonant and hl before a vowel (hlampko 'strong')

• Pro: uses familiar symbols, no font challenges

• Con: Confusion with phonemes [h] and [l] with words like (mahli 'wind',

asil.hah 'to request')

79

80

The realities of language:

variation, and standardization

80

81

Orthographic Variation

Discussion questions:

•

Is orthographic variation a problem

and if so, why?

• What kinds of variation are we likely

to encounter?

• What kinds of things can variation

represent?

81

82

Standardization

• What are some of the advantages and

disadvantages of ‘standardization’ or

‘unification’ of an orthography?

82

83

Kinds of variation

Variation at a regional level

Variation at a local level

How can these be dealt with?

83

84

Between community variation: an

example from Dene dialects

South Slavey

-tthí

tth’ih

tha

-dhe

Mountain

-pí

p’ih

fa

-ve

Déline

-kwí

kw’ih

wha

-we

Hare

-fí ‘head’

w’i ‘mosquito’

wa ‘sand’

-we ‘belt’

Should there be a common spelling for the different dialects?

84

85

The process

- Discussion of dialects: systematic

differences

- Discussion of spelling possibilities

- one spelling for all dialects?

- different spellings for each dialect?

85

86

The decision

Write each dialect with its own

symbols (e.g., tth’ih in South Slavey

and w’i in Hare)

Reasons

- transferability from English

- dialect identity

86

87

Within community variation: an

example from Dene

zha

zhú

-zhíi

ya

yú

-yíi

‘snow’

‘clothing’

‘inside’

• Some questions to ask

What might underlie this variation?

Is the variation really free?

87

88

The first decision

We began with a discussion of variation

and the different ways of dealing with it.

The first decision: standardization

-Write zh if it is ever used in that

word.

-If only y is used, write y.

88

89

And the development over time

This did not work in practice

-variation among individuals

-no resource materials

Consequence: Both zh and y are used.

Lesson: Early decisions might have to be

changed based on practice.

89

90

From related dialects to related

languages

• The Dene example shows how different sounds

are treated in closely related varieties.

• What choices might be made in representing

similar sounds in closely related languages?

• One possibility would be to choose the same

symbol.

• Another would be to represent the same sound

in different ways. This is what has happened

in Muskogean languages.

90

91

How to represent similar sounds in

closely related languages?

• The Muskogean languages include Muscogee (Creek),

Seminole Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Alabama and

Coushatta/Koasati.

• All have a phoneme /ɬ/, a voiceless lateral, but the languages

make different orthographic choices.

• Choctaw uses lh (pνlhki 'fast') before a vowel and hl before a

•

•

•

•

•

consonant (hlampko 'strong')

Chickasaw uses lh consistently (hilha 'dance')

Muscogee (Creek) uses r (rvrŏ fish)

Alabama uses ɬ (ɬaɬo 'fish')

Coushatta uses th (thatho 'fish')

Linguists vary in documentation, mostly lh or ɬ

91

92

Writing and Variation in

O'odham

• The O'odham varieties include Tohono O'odham (formerly

Papago), 'Akimel O'odham (formerly Pima), and the Mexican

variety, Sonoran O'otam.

• Multiple writing systems in use, which were developed in a

variety of contexts.

• Tohono O'odham Nation and the Salt River community use the Alvarez

and Hale orthography, which was developed as a linguist-native speaker

collaboration.

• The Saxton orthography is a practical orthography and was tested out with

native speakers, and is used in the Gila River Indian Community.

• The influence of Spanish as a transfer is leading the Sonoran O'otam to

consider another option.

• Linguist Madeleine Mathiot uses yet another system in linguistic

documentation.

92

93

Some differences in the four writing

systems for shared sounds

A&H

Saxton

Mathiot

Sonoran proposal

Long vowels

a:

ah

aa

aa

Palatals

ñ

ni

ñ

ñ

Retroflexes

ḍṣ

d sh

ḍx

sh th

Voiceless vowels ĭ

n/a

ï

n/a

Palatal affricate

c

ch

c

ch

Glottal stop

'

'

ˀ

'

Lateral flap

l

l

l

r

93

94

Sounds which vary across

dialects

• [w] vs. [v]/[ʋ] –

• Alvarez and Hale goes with w

• Saxton goes with w

• Mathiot goes with v

• Sonoran proposal goes with v

• Dialect variation within Tohono O'odham dialects for

certain vowel sequences, like io or eo hiosig vs. heosig

'flower'

• These are acknowledged and both end up being used.

94

Two types of standardization

• “Unilectal” – the most prestigious speech variety is

chosen. The rest adapt to this.

• “Multilectal” – some elements are chosen from several

dialects. No dialect is favored.

• What are some advantages and challenges of each?

95

Pros and cons

• Unilectal

• Advantage – simplicity. Once the dialect is chosen, don’t

have to focus on the others.

• Challenge – picking the dialect! What counts for “most

prestigious?”

• Appropriate when everyone can agree on “the dialect”

• Multilectal

• Advantage – doesn’t favor one group over another.

• Challenge – doesn’t represent anyone’s actual speech

• Appropriate when no clear “prestige dialect”

96

97

Standardization

Standardization often emerges as the

writing system is used; it may not be

the best starting point.

What do potential users want from

writing?

97

98

A review of the method

98

99

Methodology: a review

The ‘midwife’ approach views input from LC as

fundamental, this input consisting of:

• practice (written material produced by the LC

that concretely reveals issues for analysis,

discussion, and decision-making)

• LC insights (about the language itself,

socio-political issues, and their experiences)

• Do members of the LC regularly write/read in any

language? Are writing/reading themselves new

experiences for them? How can these new practices

be expanded and reinforced?

99

100

• The approach also relies on interwoven activities of

analysis leading to periods of experimentation of

whatever ‘decisions’ have been agreed upon, with

ongoing evaluation by the LC in both the roles of

writers and readers.

• The LC may be viewed more broadly, as in Bhutan, in

which the government is necessarily involved.

• Throughout the O.D. process, the linguist should build

ongoing written record with explanations and

examples of the analysis and discussion that went into

each decision.

100

101

The role of the Linguist

interpret LC

feedback,

looking for

clues as to:

• the functional

loads of phonol.

features

•other important

cognitive issues

• interference

issues

•socio-political

issues

monitor and interpret

written input

practice

analysis

evaluation

LC

analysis

choices

organize analysis

and discuss

options

practice

suggest further practice

and record decisions

101

102

Some further issues

functional load

cognitive needs

socio-political issues

technological issues

who is the audience?

102

103

Evaluating the ‘functional load’ of suprasegmental features: examples from Kotiria

In Kotiria, three suprasegmentals are associated to root

morphemes : nasalization, glottalization, and tone

• Minimal pairs are found for all three:

wãhã

do’a

kóró

kórò

‘drag/row’

‘kill’

doa

hu

hũ

maa

ma’a

khòá

khóá

sa’a

sã’ã

waa

wa’a

sóà

sóá

kha

khã

wama

wa’ma

báa

baá

waha

‘smoke’

‘dig’

‘hawk’

‘worm’

‘electric eel’

‘chop’

‘envy’

‘stream’

‘give’

‘name’

‘cook’

‘be small’

‘go’

‘rain’

‘leave’

‘grind’

‘young/new’ ‘decompose’

‘umbrella’

‘part/half’

‘rest’

‘swim’

103

104

However, despite shared phonemic status, each

suprasegmental feature has a different functional load.

This variation is manifested in spontaneous writing and has been

discussed throughout the o.d. process.

nasalization

•

•

•

•

glottalization

***

++ salient

(Roots / Suffixes)

++Min.Pairs

value unaffected by

morphological

processes

• always marked in

spontaneous writing

**

•

•

•

•

+ salient

(Roots only)

++M.Ps

reductions occur in

morphological

processes

• marked most, but not

all, of the time in

spontaneous writing

tone

*

• + salient

• (Roots, few

Suffixes)

• +M.Ps

• melody variable

in morphological

processes

• not marked in

spontaneous

104

writing

105

Recognizing cognitive issues:

In Kotiria root morphemes, internal voiceless Cs are

always pre-aspirated, a regular allophonic variation.

From the purely linguistic perspective, this aspiration

would not need to be represented in the orthography.

Thus, the words

could be written as:

[dahpo] ‘head’

[mahsa] ‘people/beings’

[tuhti] ‘to bark’

[puhka] ‘blowgun’

[dahʧo] ‘day’

dapo

masa

tuti

puka

dacho

105

106

However, given the salience of this aspiration

and the fact that when written, it helps readers

identify the root morpheme in a word, the decision was

made to represent this pre-aspiration in the orthography.

+ articulatory

salience

+ root recognition in reading

Thus, the words

[dahpo]

‘head’

[mahsa] ‘people/beings’

[tuhti] ‘to bark’

[puhka] ‘blowgun’

[dahʧo] ‘day’

are written as:

dahpo

mahsa

tuhti

puhka

dahcho

106

107

Examples of symbolic-political choices

in o.d. in Kotiria

Use of the symbol ‘k’ over ‘c/q(ui/e) – a macro-level choice, to

distinguish the writing system of the indigenous language from

those of the national languages (Spanish/Portuguese)

Use of the symbol ‘ʉ’ over ‘ɨ’ – a regional-level choice, to

differentiate the orthography of a minority indigenous language

from that of the locally dominant indigenous language (Tukano

proper)

Variation between use of the symbols ‘w/v’ among the Kotiria

from different regions – a group-internal choice distinguishing

sub-groups within the Kotiria population

107

An attempt to standardize

• In the 1980’s, the Ghana Alphabet Standardization Committee

was formed to standardize the set of symbols that could be used

in Ghanaian language alphabets.

• Case: [tʃ] sound was written as:

<tʃ> , <ts> ,

<c> , <ch> , <ky> , <tsch>

• Which one to choose? The answer was obvious, both to me (just

observing) and to others on the Committee…

• I thought “of course, <ch>. Why?

• Committee member said “The choice is obvious:

<ky> !”

• That was used in his language, Akan, the biggest language in

Ghana. “Obviousness”: depends on your background.

109

Cognitive/social issues: Phonemic-based

systems might prove unpopular

Choosing English-based writing systems over

phonemic systems

Navajo code talkers

wol-la-chee

shush

moa-si

klizzie

‘ant’

‘bear’

‘cat’

‘goat’

Young and Morgan

dictionary

wóláchíí’

shash

mósí

tliízí

109

110

Familiarity with English-based

systems

Eastern Pomo

phonemic

orthography

káli

do:l

lé:ma

local English

-based orthography

caw lee

‘one’

dole

‘four’

leh ma

‘five’

110

111

One more factor

• What is the writing system for? What does a

writer/reader want from it?

primacy or written text?

valuable information about the speaker?

symbolic system?

something else?

111

112

Writing Systems for Endangered Language

Communities

• Issues when literacy is used for second language

teaching because of transfer effects.

• O'odham has a high central vowel, IPA /ɨ/. All the writing

systems in the U.S. use the symbol e to represent this.

The language uses l to represent a flap (IPA /ɺ /), another

possible point of confusion.

• Muscogee (Creek) uses r for the voiceless lateral

(IPA /ɬ/).

• Can hinder learner awareness of the unique sounds of

the endangered language because of literacy in the

majority language.

112

113

Parameters: Socio-political

• need for community involvement in o.d. process

• acceptability of orthography (locally and in larger

context)

• relationship with dominant language – use of

conventions

• symbolic issues (±differentiation)

• literacy transference issues (±learnability)

• standardization / variation

113

114

Parameters: Techno-linguistic

Representation: what to represent, how to represent it,

where to represent it

• choice of script, symbols, conventions

• identification of phonemes/allophonic

processes/other phonological processes/

morphological processes

• evaluation of functional loads

• evaluation of resources where information can be

registered, if not in the orthography itself (practical

grammar, dictionary, etc.)

114

115

Parameters: Psycho-cognitive

‘Learnability’ (Orthographic depth)

• shallow O: (close to pronunciation)

•

+ learnability for beginners and non-(fluent) speakers

•

- readability (may obscure morpheme identities)

• harder to standardize dialect variation

• deep O: (preserves graphic ID of meaningful elements)

• - learnability for beginners and non-(fluent) speakers

• + readability

• easier to standardize dialect variation

115

More on reading and writing

• Underrepresentation – using fewer symbols

than phonemes that exist in the language

• Can you think of an example?

• Example: Akan (Ghana) has contrastive nasalization

on vowels, contrastive tone, and 9 phonemic vowels.

Tone and nasalization are not marked, and 7 vowels

are represented in the orthography (developed over a

hundred years ago).

• Underrepresentation

• What are the general implications for reading?

• Since you can’t distinguish phonemic contrasts,

reading is more difficult

• For writing?

• Writing could be easier, since you don’t have as many

choices to make

• What can complicate this picture?

• Reading can be more difficult, but context often can

disambiguate, and fluent readers may be able to cope

with this.

• Overrepresentation – using more symbols than

phonemes that exist in the language

• Can you think of an example?

• Koteria <d>, <r> for /d/.

• Choctaw <a>, <v> for /a/.

• All cases where different allophones are represented

• Overrepresentation

• What are the general implications for reading?

• Need to be taught two symbols for a phoneme, but

the shallow orthography can be easier to read

• For writing?

• Writing could be harder, since you have to deliberately

think about which symbol to use.

• What can complicate this picture?

• The salience of different allophones can make a big

difference. If speakers are aware of the allophones, then

fewer problems.

More on Politics: SE Asia

(condensed from Adams, Larin. 2014. Case studies of orthography decision making in

Mainland Southeast Asia. In Cahill & Rice (eds.), Developing Orthography for Unwritten Languages. )

• Scripts are not neutral. Commonly:

• i) use a variation of the national script, sometimes by

governmental decree

• ii) use a romanized script

• Complications

• But languages can cross borders, complicating matters.

Which national script?

• Competing religious identities: Buddhist, Christian, Muslim,

Animist.

Buddhist and Christian (Protestant and/or Catholic) often

have local associations.

Case study: E and H

• A man, “J” was sent to the capital to find help in

developing an orthography, starting a literacy program

(train teachers, provide production workshops, pay for

publishing) and translating the Bible into H. Contacted

SIL, as a known organization.

• At first, no way to verify J as legitimate rep of H. (He

was.)

• J said the project should include H and E (he said E

was a very close dialect of H)

• H had formed a literacy committee

• 3 people from H were invited to a literacy workshop

E and H: money

• After the workshop, participants given funds to

promote literacy in their villages: teaching nonreaders, publication of ‘literate’ by-products such as

calendars or brochures for special events.

• Difficult to monitor how these funds are actually used.

• One effect of participants returning from the workshop

in the capital with money was to create interest.

However, in this case the interest now appears to have

been more about money and less about literacy.

E and H: contact by E

• The next literacy workshop a few months later

included a new delegation of E speakers. They

claimed to represent the E group mentioned by J.

• E had no organizational equivalent of H that could

have deputized this delegation of E speakers.

However, this was not known and they were treated as

co-owners to the language project, in the workshop.

E and H: conflict

• During the workshop, differences developed between H

and E. The E deputation demanded their own project (and

funding). Attempts to mediate failed.

• In retrospect, the E deputation probably cared more about

money than literacy. However, an outside organization like

SIL could not know that and instead opted to fund both legitimizing the E deputation.

• While SIL accepted the E, conflicting information led SIL

to seek more objective evidence by surveying the “E” and

“H” villages.

E and H: survey

• In a survey, one needs willing involvement of the groups. The contact

for the E group eventually agreed to the survey but said that the E

villages should be done last. The survey (a wordlist collection,

collecting some sociolinguistic data, comprehension testing)

proceeded in the H area.

• Surprise: some H villages had a substantial S minority, with only 30%

lexical similarity with H and E. H speakers understood S only if they

had been raised around S speakers. S was clearly another language.

• During survey some S speakers said that they were really H people

and the H were just a splinter of the E people. Soon it was apparent

that some E people were trying to influence the survey outcome by

running ahead and planting information in H villages with S people.

E and H: the rise of S

• The national government has a finite number of categories for

minority groups. H and E both had an official government identity,

but S did not. If S took over H’s identity then it would now be

identifiable to the government and to NGOs like SIL. So the S went

along with the attempt of some E people to skew the survey results.

• Survey found no pure E villages; they are always part of a village

whose majority is another ethnic group – M. Further, E children

primarily speak M.

• There are a number of H-only villages, and a long-standing cultural

committee which has representatives of the major religious groups.

The E group has nothing like this. Further, the S are actually a group

whose language is like the M language.

E and H: Decline into conflict

• For some time both H and E came to literacy workshops—

eventually accompanied by an S group demanding their own

language development project separate from the M language.

• What once looked like a viable single language development

project had now devolved into 4 different groups, at least 2 of

which were probably not represented by legitimate community

members.

• High level of conflict between the groups. This conflict was

either started or accelerated by beginning a language

development project—and the resulting fragmentation actually

is creating disunity, delaying literacy for all the groups.

E and H: End of involvement

• Given this situation and a growing number of legal and

physical threats against SIL personnel if they did not

meet demands of one or more of the groups, SIL

decided to cease working with any of the groups.

• Thus, language development that was stimulated by

external involvement resulted in accentuating division

in a group that needs to work together if it is to survive

in the face of a growing national culture.

E and H: Observations

1. Unity matters

2. Know who you’re working with

3. An orthography cannot extend group identity

beyond any pre-existing political or social

organization.

4. Literacy and orthographic decisions are often a

proxy forum for other social, religious or political

issues.

5. Most of the time money creates more problems than

it solves.

130

Summary: the goals

130

131

End goals of the ‘midwife’

approach

For the LC:

• a practical orthography that is a comfortable tool for both

writers and readers

• a new means of expression developed collectively, with

their own input

• empowerment, incorporating skills and resources for

future decision-making

For the Linguist:

• an experience where some of the ‘heat’ is taken off, but

where creativity is crucial

• a richer analysis, the result of L’s technical knowledge +

LC input

131

132

Some references

Good starting places:

Cahill, Michael, and Keren Rice (eds.) 2014. Developing Orthographies for Unwritten

Languages. Dallas: SIL International.

Grenoble, Lenore and Lindsay Whaley. 2006. Orthography. Chapter 6 in Saving

languages. An introduction to language revitalization. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press. 137-159.

Hinton, Leanne. 2001. New writing systems. In Leanne Hinton and Ken Hale (editors).

The Green Book of language revitalization in practice. San Diego. Academic Press.

239-250.

Lüpke, Frederike. 2011. Orthography development. In Peter K. Austin and Julia

Sallabank (editors). The Cambridge handbook of endangered languages. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press. 312-336.

Sebba, Mark. 2007. Spelling and society: The culture and politics of orthography

around the world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Seifart, Frank. 2006. Orthography development. In Jost Gippert, Nikolaus P.

Himmelmann, and Ulrike Mosel. Essentials of language documentation. Berlin:

Mouton de Gruyter. 275-299.

132

A more exhaustive list can be obtained from the CoLang course website.

133

About us

• Mike Cahill (mike_cahill@sil.org) worked on the Kɔnni orthography in

•

•

•

•

•

Ghana in the 1980’s, and has advised on several African languages since,

especially in the Gur family.

Keren Rice (rice@chass.utoronto.ca) has been working on Dene languages

in northern Canada since the 1970’s, and served on an orthography

standardization committee in the 1980’s.

Colleen Fitzgerald (cmfitz@uta.edu) has been working on Tohono O'odham

for nearly 2 decades, and on Native languages of Oklahoma since 2009.

Gwen Hyslop (gwendolyn.hyslop@anu.edu.au) has been working on

languages in Bhutan since 2006, including development of ’Ucen

orthographies for Bhutan’s endangered languages.

Kris Stenzel (kris.stenzel@gmail.com) has been working on Kotiria and

Wa’ikhana, two Eastern Tukanoan languages spoken in northwestern

Amazonia since 2000.

We welcome your feedback/comments/questions!

133