Can we be scientific in the practice of

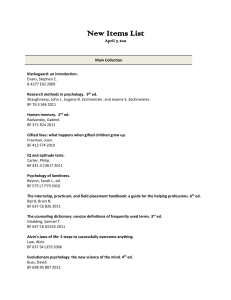

advertisement

Can we be scientific in the practice of occupational health psychology? * An homage to Don Campbell Ted Scharf, Ph.D., Research Psychologist National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Cincinnati, Ohio * Unceremoniously stolen from: Campbell, D.T. (1984). Can we be scientific in applied social science? In: Conner, R.F., Altman, D.G., and Jackson, C. (Eds.). Evaluation studies: Review Annual. v.9, 1984. Beverley Hills, Sage Publications, pp. 26-48. disclaimer – The findings and conclusions in this presentation have not been formally disseminated by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health and should not be construed to represent any agency determination or policy. Any findings and conclusions in this presentation are those of the author. please ask questions as we move along . . . Quasi-experimental methodology: Campbell, D.T., & Stanley, J. (1966). Experimental and quasiexperimental designs for research. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. Cook, T.D., and Campbell, D.T. (1979). Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis issues for field settings. Chicago: Rand McNally. Shadish, W.R., Cook, T.D., and Campbell, D.T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. Categories of validity: • statistical conclusion validity • internal validity • construct validity • external validity Campbell, D.T. (1984). Can we be scientific in applied social science? In: Conner, R.F., Altman, D.G., and Jackson, C. (Eds.). Evaluation studies: Review Annual. v.9, 1984. Beverley Hills, Sage Publications, pp. 26-48. 1. contagious cross-validation 2. competitive replication i.e. replication is the scientific response to methodological shortcomings or other problems with validity. Example: Experimentally trained researchers tend to focus on the requirements of internal validity (e.g. requiring a “true” experiment) to the exclusion of concerns related to external validity. Inappropriate use of a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT): • CDC study regarding the prevention of transmission of HIV from birth mother to baby, in Côte d’Ivoire and Thailand, using: – reduced dosage of AZT, compared to a . . . – placebo control group, rather than to the U.S. standard of care • New England Journal of Medicine, v.337, no.12, September 18, 1997 e.g.: – Angell, M. The ethics of clinical research in the third world. pp. 847-849. – Lurie, P., and Wolfe, S.M. Unethical trials of interventions to reduce perinatal transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus in developing countries. pp.853-856. In Cook and Campbell notation, the CDC research design: O1 O2 X O3 O4 -------------------O1 O2 Y O3 O4 CDC design: X = experimental, reduced AZT protocol Y = placebo participants: HIV positive, pregnant women A “comparison” group instead of a “control” group: O1 O2 X O3 O4 -------------------O1 O2 Y O3 O4 -------------------- O1 O2 Z O3 O4 Comparison groups design: X = experimental, reduced AZT protocol Y = U.S. standard AZT treatment Z = AZT protocol, midway between X & Y Remember: The “Gold Standard” - Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT): • random selection of subjects / participants • random assignment to experimental conditions • a “no treatment” or “placebo” control group • The origins of the RCT are in experimental and clinical medicine where physicians evaluate the efficacy of a particular drug or treatment • Often described interchangeably as “evidence-based” Quasi – experimental methods: • typically used with pre-existing, intact groups measure and evaluate contributing or confounding factors • between groups and within subjects analyses • compare between different treatments • origins of program evaluation methodology are in primary and secondary education • Reminder: – When a new treatment is under test, AND . . . – There is no conclusive evidence that the new treatment is more effective than the current standard, THEN . . . – We test the new treatment on a sample of eligible subjects, AND – Deliver the standard (comparison) treatment to another, different sample – AND • If there is no known effective treatment, a placebo control group may be considered as a comparison group Victora, C.G., Habicht, J-P., and Bryce, J. (2004). Evidence-based public health: Moving beyond randomized trials. American Journal of Public Health, v.94, no.3, pp. 400-405. • clinical efficacy trials • public health regimen efficacy • public health delivery efficacy • public health program efficacy • public health program effectiveness • Victora (2004) – plausibility evaluation to document impact and rule out alternative explanations, e.g. with a comparison group • complex intervention, RCT is artificial • large-scale demonstration required • ethical concerns preclude use of RCT – adequacy evaluation to document time trends • assessment of intermediate steps • evaluates each step in the presumed causal pathway Mohr, L.B. (1995). Impact analysis for program evaluation. 2ed. Thousand Oaks, CA., Sage. • “outcome line” – (especially ch.2, Fig 2.1, p.16) – preliminary, intermediate and long-term outcomes are modeled – other measured factors may influence the outcomes – figure below, adapted from Mohr (1995, p.16): Measured Activity #1 Measured Subobjective #1 Measured Activity #2 Measured Activity #3 Measured Subobjective #2 Measured Outcome of Interest Measured Activity #4 Measured Ultimate Outcome • Mohr, (1995), when: – series of related outcomes, – interim objectives, or sub-objectives, – formative evaluation required, then: – attempt to measure all relevant influences in a study Disagreements between experimentally trained researchers and researchers trained in quasi-experimental social science methodology are just one example of the ways in which our work can be considered “unscientific.” Within NIOSH: Rosenstock, L. and Thacker, S. B. (May, 2000). Toward a safe workplace: The role of systematic reviews. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. Supplement. v.18, no.4S. Rivara, F.P., and Thompson, D.C. (Eds). , pp.4-5. and the reply: NORA Intervention Effectiveness Research Team, (May, 2001). May 2000 Supplement on preventing occupational injuries. Letter to the Editor. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. v.20, no.4. pp. 308-309. Theoretical perspective (a.k.a. “world views”) can exert a great influence on the conduct of the research. Altman, I., Rogoff, B., (1987). World views in psychology: Trait, interactional, organismic, and transactional perspectives. In: D. Stokols and I. Altman, (Eds.). Handbook of environmental psychology. v.1. New York: John Wiley and Sons. World View Perspective Trait Unit of Analysis over Time person & individual psychological processes; emphasis on stable features; change is reflected in predictable, ordered, usually developmental stages. Interactional person, social, & physical environment are independent entities; interaction of the separate entities, resulting in changes of state in the separate entities. Organismic holistic entities or integrated systems composed of distinct person & environment components in interaction; interactions are predictable and trend toward homeostasis. Transactional holistic entities composed of aspects of the whole, where the aspects are mutually defining; change is continuous, intrinsic, and not pre-determined. Observers & Focus separate, objective, & detached observers; emphasis on traits and universal laws. separate, objective, & detached observers; focus on relations between separate elements. separate, objective, & detached observers; holistic systems in a hierarchy with subsystems. observers are aspects of the phenomena, yielding different observations from different observers; focus on identifying the patterns of the event under examination. Example: The “classic” hierarchy of control. I. Engineering Controls A. eliminate the hazard B. substitution of material, equipment, or process C. isolation of hazard, e.g., barriers and/or removing the worker(s) D. ventilation of airborne contaminants II. Administrative Controls to reduce exposure A. reduced work hours B. employee education and training 1. improved hazard recognition 2. improved work practices III. Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) (Adapted from Raterman, 1996, and Office of Technology Assessment, 1985.) what else do we know about hazardous work environments ?? Common features in hazardous work environments – constant change: Variability in: time space / location motion Characteristics or properties of workplace hazards: force(s) creating or causing the hazard types of efforts to control the hazard traditional hierarchy of control degree worker control likelihood of failure of controls predictability and salience work process hazard severity of risk, following exposure interactions with other hazards Worker-centered approach to hazardous work environments: Contrary to the traditional Hierarchy of Control: 1) except where a hazard has been completely eliminated from the environment, worker control and participation in managing the hazard are essential; and 2) when the work process is extremely time-limited - or is an actual emergency - workers are most likely to neglect their own safety to complete the emergent task. thus, especially in hazardous work environments, there appears to be an incompatible and conflicting set of demands that impinge on front-line workers (in particular): dual-attention demand: safety vs. productivity HOWEVER, from the point-of-view of OHP, our perspective on this problem must be: dual-attention demand: safety AND productivity How can we approach this problem? How can we train workers to adopt this perspective and attitude? brief digression: Aren’t we compromising safety when we permit considerations of productivity to enter into discussions of safety? brief digression: Aren’t we compromising safety when we permit considerations of productivity to enter into discussions of safety? Traditional workplace safety and health viewpoint: - economics and productivity never mentioned with respect to safety - to include economics is to balance a worker’s life in the same equation with the costs of production - fundamental principle: safety may not be compromised for any reason brief digression: Aren’t we compromising safety when we permit considerations of productivity to enter into discussions of safety? The real world: - safety is compromised every day on the job, especially in hazardous work environments - employees will take risks with their own lives to maintain production, (including in situations where they will not directly benefit) - especially when fatigued, attention to the production task becomes rote, and attention to changing hazards in the surrounding environment ceases brief digression: Aren’t we compromising safety when we permit considerations of productivity to enter into discussions of safety? NIOSH and others have come to realize that if we are truly interested in worker safety, we must develop realistic safety training that incorporates day-to-day productivity pressures into the training. By addressing safety in its real-world context, we: - enhance safety as a practical, usable, workplace skill - strive to incorporate safety into the production process, such that, “the safest way is also the easiest and most productive way.” (Susan Baker, Johns Hopkins) “what gets measured, gets managed” Professor Peter Chen Colorado State University University of South Australia Orlando, FL., May 18, 2011 Stokols, D. (1987). Conceptual strategies of environmental psychology. In: D. Stokols and I. Altman, (Eds.). Handbook of environmental psychology. v.1. New York: John Wiley and Sons. and Stokols, D. (1992). Establishing and maintaining healthy environments: Toward a social ecology of health promotion. American Psychologist. v.47, no.1, pp.6-22. and Stokols, D. (2006). Toward a science of transdisciplinary action research. American Journal of Community Psychology, v.38, pp.63-77. Establishing a contextual perspective; the core assumptions (Stokols, 1987, pp.42-43): 1. psychological phenomena should be viewed in the spatial, temporal, and sociocultural milieu in which they occur; 2. a focus on individuals’ responses to discrete stimuli and events in the short run should be supplemented by more molar and longitudinal analyses of people’s everyday activities and settings; 3. the search for lawful and generalizable relationships between environment and behavior should be balanced by a sensitivity to, and an analysis of, the situation specificity of psychological phenomena; 4. the criteria of ecological and external validity should be explicitly considered (along with the internal validity of the research) not only when: - designing behavioral studies, but also when: - judging the applicability of research findings to the development of public policies and community interventions. This is the search for and identification of the target phenomenon and the relevant contextual variables. The contextual variables may be identified through: - an exploratory and atheoretical process, or - a fully developed contextual theory Example: Florida Department of Health responses to the 2004 hurricane season Structural equation (two) models: 1. Both work organization and hurricane exposure measures. Purpose: to establish that the work organization measures contribute to a model in which the hurricane exposure measures are included as predictors. 2. Work organization measures alone. Purpose: to identify an upper-bound estimate for the effects of the work organization measures (i.e. without competing with hurricane exposure measures). prior hurricane training before 2004 W O R K O R G A N I Z A T I O N amount of sleep 2004 number of hurricanes worked 2004 USUHS hurricane exposure scale - 2004 prior hurricane experience before 2004 ill health 6/2005 difficulty balancing work & family 2004 return to normal 20042005 distress during hurricanes 2004 T O P I C S bad mental health days 6/2005 job dissatisfaction 2004-2005 2004 hours worked 2004 emotional experiences of hurricanes 2004 presenteeism 6/2005 p<0.001 p<0.01 p<0.05 hypothesized direction (sign of the coefficient) opposite the hypothesized direction (opposite sign of the coefficient) measured variable latent variable (construct) Structural equation (two) models: 1. Both work organization and hurricane exposure measures. Purpose: to establish that the work organization measures contribute to a model in which the hurricane exposure measures are included as predictors. 2. Work organization measures alone. Purpose: to identify an upper-bound estimate for the effects of the work organization measures (i.e. without competing with hurricane exposure measures). role conflict/ compatibility 2004 workload 2004 return to normal 2004-2005 social support 2004 safety conflict 2004 control 2004 ill - health 6/2005 difficulty balancing work & family 2004 distress during hurricanes 2004 bad mental health days 6/2005 job dissatisfaction 2004-2005 communication & work organization prob. 2004 presenteeism 6/2005 The social ecology of health promotion core assumptions (Stokols, 1992, pp.7-8): 1. efforts to promote human well-being should be based on an understanding of the dynamic interplay among diverse environmental and personal factors; 2. analyses of health and health promotion should address the multidimensional and complex nature of human environments, including: - physical and social components - objective and subjective qualities - scale or immediacy (proximal vs. distal) to individuals and groups - independent environmental attributes or composite relationships among several environmental features; The social ecology of health promotion core assumptions (Stokols, 1992, pp.7-8), continued: 3. environmental scale and complexity: - individuals - small groups - organizations - populations i.e. multiple levels of analysis using diverse methodologies; 4. dynamic interrelations (or transactions) between people and environments: - physical and social features of settings influence participants’ health - participants modify their surroundings - interdependencies between immediate & distant environments, e.g. local, state, and national-level regulations for safety & health Scope of transdisciplinary research, (Stokols, 2006, p.66): What are the disciplinary boundaries of OHP ? Put another way, what are the most important disciplines with which OHP must interact ? Some candidate disciplines that are essential to OHP: health, industrial/organizational, community, and environmental psychology, plus epidemiology, public health, occupational medicine, industrial hygiene, safety engineering, and anthropology, sociology, economics. Stokols, D. (2006). Toward a science of transdisciplinary action research. American Journal of Community Psychology, v.38, pp.63-77. and Rosenfield, P.L., (1992). The potential of transdisciplinary research for sustaining and extending linkages between the health and social sciences. Social Science and Medicine. v.35, no.11, pp.1343-1357. Continuum of collaboration disciplinary Characteristics of the degree of collaboration and subsequent approach to investigation and research the study of a scientific phenomenon from one perspective, typically reflecting 1) distinctive substantive concerns, 2) analytic levels, and 3) concepts, measures and methods; boundaries between disciplines may be overlapping, and may spawn a new focused discipline multidisciplinary different disciplines working independently or sequentially on a common problem interdisciplinary different disciplines sharing information, but the component disciplinary models and methods remain unchanged transdisciplinary researchers from different disciplines create a shared conceptual framework that integrates and extends discipline-based concepts, theories, and methods to address a common research topic. something to ask your students: “which comes first . . . the question or the answer ?” and: “where do research hypotheses come from ?” brief review: quantitative methods – - test existing hypotheses (e.g., consider or rule-out) assess concepts we have measured (quantitatively) reduce observed results to manageable findings enable systematic, replicable, and verifiable measurement, i.e. fundamental science quantitative methods do not – - generate novel explanations about things or events, e.g. propose new causal pathways - suggest explanations not previously measured qualitative methods – - describe and/or explain phenomena or events - interpret and/or “model” processes or events - may replicate and verify . . . or suggest unknown processes or relationships, at same time they provide empirical data to generate hypotheses or verify a quantifiably testable hypothesis qualitative methods provide data specific to a sample and target population from which it was derived series of qualitative interviews or focus groups produces an iterative and progressive investigation of the selected topic qualitative methods usually are not designed to – - generalize beyond the actual sample, unless data collected for this purpose, and replicated with subsequent, independent groups - test hypotheses empirically, unless the sample size is appropriate, i.e., group characteristics sufficiently known to determine heterogeneous or homogeneous, and every participant responds to each question or hypothesis Example using qualitative methods: • topic of investigation: risks for injury among family farmers, e.g. Kidd, et al., 1996 • method of investigation: series of focus groups • farm family members are judges regarding the farm environment – look for agreement between the participants both within groups and across the series of groups • sample the maximum variability in farm environments • different regions • different enterprises (crops, livestock, etc.) • different sizes of operations • each group should be relatively cohesive / homogenous Example of a qualitative method generating a model to be tested quantitatively: (+) - Physical PERCEPTION/ - Psychosocial ASSESSMENT/ - Non-Hazardous JUDGMENT (+) - Hazardous (-) PSYCHOLOGICAL Environm ental Conditions (+/-) Environm ental Conditions as Stressors (+/-) (-) SAFETY DEMAND (-) (-) MAKING (+/-) (+/-) Individual Factors (+/-) SAFETY PERFORMANCE (+) (+/-) (+) (-) Kidd, et al., 1996 (-) DECISION - Tasks, (-) CHRONIC STRAIN (+) (-) (-) Conditions (+/-) ACUTE STRESS REACTION (-) (+) Equipm ent, (+) PHYSIOLOGICAL ACUTE STRESS REACTION (-) (+) (+) (-) WORK ENVIRONMENT SAFETY MARGIN (+) (-) INCIDENT/ INJURY (-) Building a Research Team • Organizational representation (local) clinic professionals & staff business owners/managers labor union(s) representatives social service agencies • Community representation • Professional / technical expertise academia/research manufacturer(s) non-governmental organizations (NGO’s) public health & other government orgs. Also: • • • • Research subjects / patients Patient advocates Family members of clients, patients, or workers Other workers & community members • Typically NOT part of research team – why? – why not? • Traditional experimental science measures subjects’ behavior, attitudes, etc., but does not involve the “objects” of the research in the planning. • However, qualitative methods show us the way to systematically elicit research hypotheses from our subjects. • Therefore, asking members of the subject class or group to help plan the implementation of the research is just an extension of our focus group example. • Result: ordinary research / evaluation study with the insight and participation of representatives of your subjects as research team members. Example: • Simple Solutions – nursery tool development process – multi-disciplinary team from University of California, Davis – three large nursery companies • OSHA 200 logs • ergonomic checklist completed by workers and supervisors • interviews with workers and supervisors Janowitz, et al., 1998; and Prof. John Miles, personal communication, 2004. • Simple Solutions – nursery tool development process – high risk job tasks selected (high risk for workrelated musculo-skeletal disorders) – tool design involved nursery workers and university team • workers and team – together – designed the tools • imperfect or incorrect designs were manufactured because workers made the suggestion • then the workers helped design improvements Janowitz, et al., 1998; and Prof. John Miles, personal communication, 2004. Summary: Participatory Action Research (PAR) in hazardous work environments. Project Partners Partners’ role Researchers’ role Kentucky Kentucky Describing, explaining, Creating a model based on Farm Family farmers and interpreting the key the farmers’ interpretations Health and issues and how these Hazard topics are linked. Surveillance Program Cross-cutting KY livestock Iteratively developing and Recording and organizing the Research and farmers/ testing checklist items; results; seeking input from Interventions ranchers prioritizing checklist items; independent subject matter in Hazardous Small suggesting modifications experts; editing the final lists; Work and additional items in developing formal evaluation construction Environments company subsequent iterations studies with new groups of workers. owners in KY Hazard Journeymen Participate in exploratory Developing and revising recognition: ironworkers; and confirmatory focus focus group interview guide; preventing primarily groups; confirmatory probing new areas of inquiry falls and apprentice groups proposed the identified by focus group close calls trainers project: “Unreported participants; identifying new Incidents...” (below). questions based on the focus group statements. Proposed project: Unreported Incidents, Injuries, & Illnesses with Ironworkers. Core team composed of journeymen ironworkers who train apprentices in union locals. Create, direct, and implement an investigation of the actual number of incidents, injuries, and illnesses among Ironworkers, starting with apprentices. Technical support to the project: assembling Core Team decisions into the components of a research project; HSRB protocol and review; developing analytic templates for reporting the findings. p – 2 – r results Model: “Linking stress and injury in the farming environment:...” Checklist: Safe Cattle Handling Critical Action Factors. Checklists: Guidelines for Extension Ladder Safety Summary of the focus group findings Goal: on-going electronic surveillance tool for use by the Ironworkers and other union locals. What does all this mean for OHP, NIOSH and all of CDC? National Institute FOR Occupational Safety and Health National Center FOR Injury Prevention and Control National Center FOR Environmental Health National Center FOR HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention National Center FOR Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion All in the: Centers FOR Disease Control and Prevention Conclusion: like NIOSH, Occupational Health Psychology promotes safety and health at work. Perspective on evaluation methodology: • Health care interventions, changes to improve workplace safety and health, and even pre-placement exams are (essentially) components of natural experiments • Identifying and developing systematic measurements of interventions and workplace programs are tasks of research • Once systematic measurements are collected, the interventions and workplace programs will then include a study of intervention effectiveness • Results from the evaluation of effectiveness may be used to: – improve current effectiveness – identify additional program needs – promote diffusion of the intervention to additional communities, occupations, other participants Interventions for injury prevention and health promotion, or a few specifics that illustrate the preceding discussion: Training style: • • • • • • • learner centered training active participation problem solving discussions among / between co-workers crew-based solutions to problems encourage creative approaches to problems transfer of skills from experienced to less experienced job / task performers • • site-specific focus, especially with intact work crews: discuss prior workplace hazards, problems, and the solutions developed • promote crew approaches to specific problems on-site Training principles: • front-line worker control is essential where hazards are present • promote good communication, cooperation, and preplanning between workers and front-line supervisors • safety is a skill • integrate safety with production as the performance standard, i.e. safety and productivity are interdependent in the work organization and processes • subject-matter experts (including veteran workers) identify hazards and develop plans to reduce risk Training principles - 2: • hazard recognition: • is not simply identifying existing problems in the work environment • includes anticipating incipient problems that may be likely to develop • once identified, hazards can be prioritized for elimination or mitigation, with an emphasis on reducing risk • crew-based solutions promote: • improved safe-work practices • reduction in variability on critical tasks • improved safety climate References: Altman, I., Rogoff, B., (1987). World views in psychology: Trait, interactional, organismic, and transactional perspectives. In: D. Stokols and I. Altman, (Eds.). Handbook of environmental psychology. v.1. New York: John Wiley and Sons. Angell, M. (1997). The ethics of clinical research in the third world. New England Journal of Medicine. v.337, no.12. (September 18, 1997.) pp.847-849. Baron, S., Estill, C.F., Steege, A., and Lalich, N., (Eds.) (2001). Simple solutions: Ergonomics for farm workers. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Cincinnati, Ohio. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2001-111. Campbell, D.T. (1984). Can we be scientific in applied social science? In: Conner, R.F., Altman, D.G., and Jackson, C. (Eds.). Evaluation studies: Review Annual. v.9, 1984. Beverley Hills, Sage Publications, pp. 26-48.) Campbell, D.T., & Stanley, J. (1966). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. Cole, H.P. (1997). Stories to live by: A narrative approach to health behavior research and injury prevention. In: Gochman, D.S., ed. Handbook of health behavior research IV: Relevance for professionals and issues for the future. New York, NY: Plenum Press., pp. 325-349. Cole, H.P., Lehtola, C.J., Thomas, S.R., and Hadley, M. (2005). No way to meet a neighbor, 2ed. Simulation exercise. Available at: http://nasdonline.org/document/1014/9/d000997/thekentucky-community-partners-for-healthy-farming-rops-project.html. References - 2 Cole, H.P., Lehtola, C.J., Thomas, S.R., and Hadley, M. (2000). Facts about tractor/motor vehicle collisions. Available at: http://nasdonline.org/static_content/documents/1014/TMVC%20doc.pdf. Cook, T.D., and Campbell, D.T. (1979). Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis issues for field settings. Chicago: Rand McNally. Glascock, L.A., Bean, T.L., Wood, R.K., Carpenter, T.G., and Holmes, R.G. (1995). A summary of roadway accidents involving agricultural machinery. Journal of Agricultural Safety and Health. v.1, no.2, pp.93-104. Janowitz, I., Meyers, J.M., Tejeda, D.G., Miles, J.A., Duraj, V., Faucett, J., and Kabashima, J. (1998). Reducing risk factors for the development of work-related musculoskeletal problems in nursery work. Applied Occupational & Environmental Hygiene. v.13, no.1, pp 9-14. (Now published as the Journal of Applied Occupational & Environmental Hygiene.) Kidd, P.S., Scharf, T., and Veazie, M.A. (1996). Linking stress and injury in the farming environment: A secondary analysis of qualitative data. In: C.A. Heaney and L.M. Goldenhar, (Eds.). Health Education Quarterly. Theme: Worksite health programs. v.23, no.2, pp. 224-237. Kowalski, K.M., Fotta, B., and Barrett, E.A. (1995, August). Modifying Behavior to Improve Miners' Hazard Recognition Skills Through Training. Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth annual Institute on Mining Health, Safety and Research. Blacksburg, VA, pp.95-104. References - 3 Lurie, P., and Wolfe, S.M. (1997). Unethical trials of interventions to reduce perinatal transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus in developing countries. New England Journal of Medicine. v.337, no.12. (September 18, 1997). pp.853-856. Mohr, L.B. (1995). Impact analysis for program evaluation. 2ed. Thousand Oaks, CA., Sage. National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (2011, April). Early estimate of motor vehicle traffic fatalities in 2010. Traffic Safety Facts: Crash Stats. DOT HS 811 451. Available at: http://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/Pubs/811451.pdf National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (2011, July). Seat belt use in 2010 – Use rates in the states and territories. Traffic Safety Facts: Crash Stats. DOT HS 811 493. Available at: http://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/Pubs/811493.pdf National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (2008). 2006 motor vehicle occupant protection facts. DOT HS 810 654. Available at: http://www.nhtsa.gov/DOT/NHTSA/Traffic%20Injury%20Control/Articles/Associated%20Files/810 654.pdf. NORA Intervention Effectiveness Research Team, (May, 2001). May 2000 Supplement on preventing occupational injuries. Letter to the Editor. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. v.20, no.4. pp. 308-309. References - 4 Office of Technology Assessment, U.S. Congress. 1985. Preventing Illness and Injury in the Workplace. ch.9, pp.173-185. OTA-H-256 Washington, D.C. Perdue, C., Kowalski, K.M., and Barrett, E.A. (1994). Hazard Recognition in Mining: A Psychological Perspective. US Bureau of Mines, Department of the Interior, Circular IC #9422. Raterman, S.M. 1996. Methods of control. In: Plog, B.A., Niland, J., and Quinlan, P.J., (eds). Fundamentals of Industrial Hygiene. 4th ed, ch.18, pp.531-552. National Safety Council, Itasca, IL. Revised from: Olishifski, J.B. 1988. Methods of control. In: Plog, B.A., Benjamin, G.S., and Kerwin, M.A. (eds). Fundamentals of Industrial Hygiene. 3rd ed, ch.20, pp.457-474. National Safety Council, Chicago, IL. Rethi, L., Flick, J., Kowalski, K., and Calhoun, R. (1999). Hazard recognition training program for Construction, maintenance and repair activities. Pittsburgh, PA., DHHS (NIOSH): 99-158. Robson, L.S., Shannon, H.S., Goldenhar, L.M., and Hale, A.R. (2001). Guide to evaluating the effectiveness of strategies for preventing work injuries: How to show whether a safety intervention really works. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Cincinnati, Ohio. Institute for Work and Health, Toronto, Canada. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2001-119. Rosenfield, P.L., (1992). The potential of transdisciplinary research for sustaining and extending linkages between the health and social sciences. Social Science and Medicine. v.35, no.11, pp.1343-1357. References - 5 Rosenstock, L. and Thacker, S. B. (May, 2000). Toward a safe workplace: The role of systematic reviews. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. Supplement. v.18, no.4S. Rivara, F.P., and Thompson, D.C. (Eds). , pp.4-5. Scharf, T., Hunt, J., III, McCann, M., Pierson, K., Repmann, R., Migliaccio, F., Limanowski, J., Creegan, J., Bowers, D., Happe, J., and Jones, A. (2011). Hazard Recognition for Ironworkers: Preventing Falls and Close Calls – Updated Findings. In, Hsaio, H., Keane, P. (Eds.). “Research and Practice for Fall Injury Control in the Workplace: Proceedings of International Conference on Fall Prevention and Protection.” Morgantown, WV., NIOSH. May 18-20, 2010. Scharf, T., Vaught, C., Kidd, P., Steiner, L., Kowalski, K., Wiehagen, B., Rethi, L., and Cole, H. (2001). Toward a typology of dynamic and hazardous work environments. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment. v.7,no.7, pp.1827-1841. Shadish, W.R., Cook, T.D., and Campbell, D.T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. Stokols, D. (1987). Conceptual strategies of environmental psychology. In: D. Stokols and I. Altman, (Eds.). Handbook of environmental psychology. v.1. New York: John Wiley and Sons. Stokols, D. (1992). Establishing and maintaining healthy environments: Toward a social ecology of health promotion. American Psychologist. v.47, no.1, pp.6-22. References - 6 Stokols, D. (2006). Toward a science of transdisciplinary action research. American Journal of Community Psychology, v.38, pp.63-77. Victora, C.G., Habicht, J-P., and Bryce, J. (2004). Evidence-based public health: Moving beyond randomized trials. American Journal of Public Health, v.94, no.3, pp. 400-405. Villarejo, D., Lighthall, D., Williams, D., Souter, A., Mines, R., Bade, B., and Samuels, S., (2000). Suffering in silence: A report on the health of California’s agricultural workers. California Institute for Rural Studies, Davis, CA. Available at: http://www.cirsinc.org/news.html#SiS Wiehagen, B., Conrad, D., Friend, T., and Rethi, L. (2002). Considerations in training on-the-job trainers. pp.27-34. In: Peters, R.H., (Ed.). Strategies for improving miners’ training. Information Circular 9463. Pittsburgh, PA., DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2002-156. Wiehagen, W.J., Conrad, D.W., and Baugher, J.M. (2006). Job training analysis: A process for quickly developing a roadmap for teaching and evaluating job skills. Information Circular (IC) 9490. Pittsburgh, PA: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Pittsburgh Research Laboratory, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2006-139. August, 2006. Wiehagen, W.J., Lineberry, G.T., and Rethi, L.L., (1996). The Work Crew Performance Model: A Method for Defining and Building Upon the Expertise Within an Experienced Work Force, SME Transactions, Vol. 298, pp. 1925-1931. Thank you . . . .