Contracts I – Maggs

advertisement

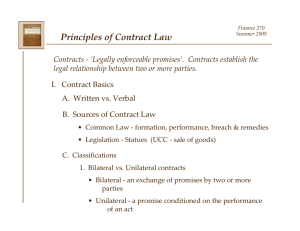

Contracts Final Outline – Professor Maggs I. BASES FOR ENFORCEMENT A. Requirement of a Basis for Enforcement General Principles: 1. When Π sues Δ for breach of contract, Π claims Δ made a promise and didn’t keep it. Π asks court to enforce the promise. Feinberg, Mills 2. Court will not enforce Δ’s promise unless Π can show a basis for enforcement. 3. 3 Modern bases for enforcement: consideration, reliance, and, in a few special cases, “moral obligation.” 4. In defense, Δ may argue Π cannot show one of the three bases for enforcement. B. CONSIDERATION as a Basis for Enforcement 1. General Rule: Consideration for Δ’s promise may be (1) either a promise or a performance that was (2) bargained for in exchange for the Δ’s promise 2. Δ’s Arguments: Δ will argue that there is no consideration b/c these two elements have not been met; a. ARGUMENTS FOR WHY THERE IS NO VALID PROMISE OR PERFORMANCE: i. The promise given in exchange is a promise to settle an invalid claim, and Π did not have a good faith and reasonable belief in the possible validity of the claim. Cf. Fiege v. Boehm- Fiege promised to pay Boehm child support, she agreed not to instigate bastardy proceedings; Held- there was consideration; she had reasonable good faith belief he was father/ that the agreement was valid ii. The promise given in exchange is illusory b/c it does not impose any express or implied commitment and cannot be consideration. Strong v. Sheffield- Strong promised to forbear cashing in on a promissory note for unspecified amt. of time if his niece would endorse it; Held- no consid. b/c promise to forbear was illusory, he could have cashed it in the next day But see Mattei v. Hopper- Mattei, Π, wanted Hopper’s land for a mall but contract said Mattei could back out if no leases, Hopper- no consid.; Held- is consid., implied term Mattei will operate in good faith; Wood v. Lucy, Lady DuffGordon- Wood made “implied promise to use reas. efforts” marketing DG’s s clothing line, she broke contract, entering deal w/Sears; Held- promise to represent interests of a party is suff. consid. even if promisee not specifically mandated to act (terms implied in fact) Express terms- what you specify aloud; Implied terms- implied in fact (terms a reasonable person would infer to exist) and in law (in law- based on state policy, imposing duty of good faith and fair dealing) b. ARGUMENTS FOR WHY THERE IS NO VALID BARGAINED FOR EXCHANGE: i. The promise/performance given by Π had already been received by Δ and thus was not given in exchange for Δ’s promise Feinberg v. Pfeiffer- Pfeiffer Co. promised Feinberg a pension, she then retired, they stopped payments; Held- past service cannot be consideration ii. The promise or performance given by the Π was not given until after the Δ’s promise, and thus was not given in exchange for the Δ’s promise. (Feinberg; Strong v. Sheffield) 1 But see Central Adjustment v. Ingram- Held- the actual employment for 2 yrs. of 3 employees was consideration for employee’s promise not to compete; even tho the actual employment did not occur until after they’d made promise- doesn’t square w/bargain theory iii. The Δ’s promise was a conditional promise to make a gift. Π may have taking actions to satisfy the condition, but Δ did not seek these actions in exchange for Δ’s promise. Kirksey v. Kirksey- Δ wrote sister-in-law, Π, offering her a place to live if she would “come down and see me”; Held- Δ’s promise = just a condition; no consid. iv. The purported bargained for exchange was just a sham. c. INVALID ARGUMENTS FOR WHY THERE IS NO CONSIDERATION: i. The promise/performance given by Π cannot be consideration, even tho it was bargained for, b/c it did not benefit the Δ or impose a detriment on the Π. Hamer v. Sidway- nephew promised not to drink/smoke/gamble in consideration for Uncle’s promise to give him $5k. Held- not necessary the promisor benefit or promise experience detriment- also in Rest. 2d § 79. ii. The promise/performance given by Π cannot be consideration b/c it was less valuable than the Δ’s promise. (Fiege) C. RELIANCE as a Basis for Enforcement 1. Definition: When a court enforces a promise on basis of reliance, the court is said to be enforcing it by means of “promissory estoppel.” 2. General Rule: To enforce a promise based on reliance, Π must show not only reliance but also 4 other elements. Π must show that: (1) the Δ made a promise; (2) the Δ could reasonably expect the Π to take an action; (3) the Π took an action/forbearance; (4) the action was induced by (i.e., taken in reliance on) the promise; and (5) enforcement of the promise is necessary to prevent injustice. Rest. 2nd § 90 (p. 231). 3. Δ’s Arguments: Δ will argue Π cannot show one or more of the elements. Examples: a. The promise did not induce the Π to take any action that the Π would not have taken anyway. (Feinberg- she quit work early b/c of reliance on the pension; Pfeiffer Co. tried to argue she would have retired anyway, but Court disagreed) b. Enforcement of the promise is not necessary to prevent injustice. i. Feinberg (Pfeiffer argued she could get another job; Court rejected); Cohen v. Cowles Media- Cohen gave newspaper info, wanted anonymity, they published his name, he was fired; Held- using his name wasn’t necessary; enforcing their promise was b/c unjust to him for him to get fired 4. Policy reasons for promissory estoppel: (1) underlying theme of justice- certain promises should be enforced; (2) people ought to be able to rely on promises. D. “MORAL OBLIGATION” as a Basis for Enforcement 1. General Rule: Moral obligation is not a general basis for enforcing a promise a. Mills v. Wyman- Levi Wyman fell ill,cared for by Mills for 2 wks, then died; then Levi’s Dad promised to pay Mills, didn’t; Held- unenforc. b/c no consid.; just immoral 2. Recognized Special Cases: Even if Π cannot show consideration or reliance, 3 types of promises are said to be enforceable on the basis of “moral obligation.” A Court will enforce a new promise by Δ to reaffirm an old obligation that was: (1) discharged by a statute of limitations (§ 82); or (2) discharged by bankruptcy proceedings (§ 83); or (3) voidable b/c of Δ’s prior infancy (§§ 14, 85). 2 No consideration for these promises, but they are enforceable on the basis of moral obligation. 3. Possible New Special Case: A few courts will enforce a Δ’s promise to pay the Π money in recognition of a material benefit that Π conferred on Δ. § 86(1) But most states disagree. a. Webb v. McGowin- Π, working at mill, saw boss, Δ McG below; Webb fell w/75 lb. block to prevent it from hitting McG, becoming crippled; McG died, payments stopped; Held- Δ morally bound to continue compensating Π b. But see Dementas v. Estate of Tallas- Tallas wrote memo of intention to change his will to give his helpful friend, Dementas, $50k; Held- not enforceable on basis of moral obligation; no consideration and no reliance 4. Δ’s Argument: Δ will argue that the promise is not one of the special kinds of promises that courts will enforce on the basis of moral obligation. E. RESTITUTION as a Substitute for Enforcement 1. General Rule: when the Π cannot prove that the Δ made an enforceable promise, the Π may seek “restitution” from Δ if Δ has been unjustly enriched at Π’s expense. Δ must pay the reasonable value of any benefit receives from Π. a. Cotnam v. Wisdom- Dr. Wisdom, Π, performed emerg. surgery on Harrison after carwreck; Rst. §155- compensat’n for service in implied contract shld = value of services 2. Δ’s Arguments: Δ will argue that there has been no unjust enrichment at the Π’s expense. Examples (these types of Πs usually do not prevail in Restitution cases): a. There has been no enrichment b/c the Π conferred the benefit as a volunteer, manifesting no expectation of compensation. (Drs not volunteers b/c it’s how they make a living.) § 57 b. There has been no enrichment b/c Π conferred the benefit as a officious intermeddler. § 2 c. There has been no unjust enrichment at the Π’s expense b/c Π has other remedies. § 110 i. Callano v. Oakwood Park- Callanos contracted w/Pendergrast (buying a house from Oakwood) to plant shrubs, Pend. died, house sale cancelled, Call’s sue Oakwd; HeldΠ’s remedy is against Pend’s estaste (Oakwd not liable), who can recover from Oakwd II. CONTRACT FORMATION A. Assent 1. General Rule: A court will not enforce the Δ’s promise if the Π actually knew, or a reasonable person would have known that the Δ was not assenting to be bound. a. Lucy v. Zehmer- Zehmers, drinking at bar, promised Lucy to sell him their farm for $50k; Held- a reasonable persona’s interpretation of the outward intention matters, not that they may have been just jesting; Evidence that contract was legit. b. Intent is difficult to judge b/c there may be multiple viewpoints c. General policy that contractual liability should be voluntary. B. Offer and Acceptance 1. General Rule- If the Π alleges Δ made a promise as part of a bargain, a court will not enforce the promise unless Π can prove existence of both an offer and acceptance. 2. Specific Rules: a. An offer is a manifestation of willingness to enter a bargain, conditioned on the offeree’s acceptance. i. Preliminary negotiations vs. offer: inherent ambiguity, reluctantance to find offers b/c contractual liability should be voluntary, objective inquiry in deciding ii. Owen v. Tunison- Owen, Π, wrote he was interested in buying Tunison’s property; Tunison wrote back that he would not sell it for less than $16k, Owen replied, saying he accepted, Tunison declined; Held: Δ’s letter was just preliminary negotiations 3 iii. Harvey v. Facey- Harvey, Π, telegraphed: Telegraph lowest cash price for Bumper Hall Pen, Facey: Lowest price 900 pounds, Harvey: We agree to buy for 900 pounds; Held- No legit. offer, the statement of the price was preliminary negotiations iv. Fairmount Glass v. Crunden-Martin- C-M, Π, wrote: lowest price for order?; Fairmt, Δ, wrote: here is our offer, for immed. acceptance; Π- We accept; Δ- imposs. to book order, sold-out; Held- There was an offer & acceptance, not just a quote of prices b. Advertisements generally are not offers unless they state a limited quantity or have other attributes indicating that the advertiser actually intended to make an offer. i. Lefkowitz v. Great Minn. Surplus Store- advert. for stole for $1; store refused to give to Lef b/c of “house rule”- women only; Held- advert. was an offer b/c clear, definite, didn’t say house rule, advertiser can’t impose new conditions after acceptance c. Did the offeree accept? 6 questions to figure out: i. What was the offer? ii. What type of acceptance did the offer invite? iii. Did the offeree completely perform or promise to perform as invited? Note- sometimes offeree implicitly promises to perform by starting work. iv. If the offeree promised to perform, was the promise made in a manner permitted by the offer? v. What type of acceptance is required (complete performance, promise to perform)? vi. Did offeree provide notice of acceptance? d. IN GENERAL, AN OFFER TERMINATES AND CANNOT BE ACCEPTED AFTER: i. The offer lapses b/c the passage of time § 41 An offer lapses after the time specified or after a reasonable time if no time is specified. ii. The offer has been revoked by the offeror. §§ 42, 43 Revocation of an offer is effective when communicated, directly or indirectly, to the offeree. o Dickinson v. Dodds-; Dick found out informally the property was being sold to another; Held- no obligation to keep offer open b/c no consid.; before complete acceptance by Dick, Dodds could contract w/another An offeror generally can revoke an offer at any time before acceptance (can be indirect), unless the offeror has made an enforceable promise (called an “option contract”) to keep the offer open. (Dickinson- Court held promise to keep offer open until Fri. unenforceable b/c he hadn’t received consideration) A few courts hold that an offeror cannot revoke an offer if the offeree has relied on the offer. o Drennan v. Star Paving- Π, general contractor, relied on Δ Star Paving’s offer in submitting a large bid; Held- enforceable on promissory estoppel; Π’s reliance makes Δ’s offer irrevocable iii. The offer has been rejected by the offeree. § 38 (1) A counteroffer is presumed to be the rejection of an offer. § 39 (1), (2) o Minn. & St. Louis Rwy. v. Columbus Rolling Mill - Π, Rwy., rejected by making new offer; Held- a proposal to accept on terms different from those offered = rejection of offer, ending the negotiation, unless other party accepts 4 Under the MIRROR IMAGE RULE, a purported acceptance of an offer that contains different or additional terms is treated as a rejection and a counteroffer. (Minn. & St. Louis Rwy.) iv. The offeror has died. §48 An offer terminates upon the death of the offeror, even if the offeree does not have notice of the offeror’s death, unless the offeror has entered an option contract to keep the offer open. No req. of notice. o Cf. Earle v. Angell- nephew agreed to come to his Aunt’s funeral; Issue- was it unilateral (requiring performance- not accepted until completely performed, thus not enforceable against estate) or bilateral (-promise- enforceable) e. MAILBOX RULE- unless the offer specifies otherwise, acceptance occurs upon dispatch of the acceptance. f. Complete/ Partial Performance: i. If an offer invites acceptance by the rendering of a complete performance, acceptance does not occur unless and until the offeree completely performs. Cf. Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball- Carbolic Co., Δ, - flu prevention device, advertised if you use, get flu, monetary reward; Carlill followed directions, got flu; Held- here notice of acceptance by Carlill not necess. b/c the Co. did not require it ii. An offeree may accept by making a promise to render complete performance either expressly w/words or implicitly through some sort of conduct. The most common way to make an implicit promise to render complete performance by conduct is to start performing. White v. Corlies & Tift- White, builder, Π, gave estimate for office renovation; Δs made change to estimate, asking for agreement; Π just began working, then Δs countermanded; Held- Π should have given assent before beginning working Ever-tite Roofing v. Green- Greens, Δ, made contract w/E-T, then hired someone else; gave notice when E-T showed up to start roofing; Held- Notice must be given before commencement of performance; commencement began when trucks loaded Allied Steel v. Ford Motor- Allied had begun working but argued the contract had not yet been accepted; Held-acceptance of an offer by part performance in accordance w/the terms of the offer is sufficient to accept the contract iii. If the offer invites acceptance by rendering complete performance, notice of acceptance is not required unless requested. (Carlill) g. Even if an offer describes one manner of making a promise, the offer also may permit other manners. (Allied Steel v. Ford Motor) i. International Filter v. Conroe Gin- Int. Fil. employee gave proposal (prelim. neg.) to Conroe, who agreed sent to Pres. of Int. Fil., who accepted it (nec. for contract); a mngr of Int. notified Conroe it was accepted; Held- notification of exec’s approval didn’t have to be made- it became a contract when the Pres. signed h. The offeree’s silence cannot be an acceptance, except in a few special cases, such as when the parties’ course of dealing makes silence a proper method of acceptance. § 69 i. Hobbs v. Massasoit Whip Co.- Held- Massasoit required to pay, even though they’d silently accepted b/c they had previous dealings where skins sent/accepted same way ii. Exceptions: offeree accepts services by taking the benefit, previous dealings, offeror says silence is acceptance and offeree intends to accept 5 i. If the offer invites acceptance by making a promise, notice of acceptance is required unless it is waived. (White, Ever-Tite Roofing, International Filter) 3. Δ’s Arguments: a. There was no offer (manifestation of a willingness to be bound upon offeree’s acceptance). (Owen, Harvey, Fairmount Glass, Lefkowitz ) b. The offer lapsed before the attempted acceptance. c. The offer was revoked by the offeror before the attempted acceptance, and there was no valid option contract precluding revocation. (Dickinson) d. The offer was expressly rejected by the offeree before the attempted acceptance. e. The offer was implicitly rejected by the offeree b/c the offeree made a counteroffer. (Minn. & St. Louis Rwy.) f. The offer terminated before the attempted acceptance b/c the offeror died. (Earle) g. The offer invited acceptance by the rendering of complete performance, and the offeree did not completely perform. h. The offer invited acceptance by a promise to render complete performance, and the offeree did not make such a promise either expressly w/words or implicitly w/conduct. (White, Ever-Tite) i. The offer invited acceptance by a promise to render complete performance and, although the offeree made a promise, the offeree did not make the promise in a manner invited by the offer. (Allied Steel) j. Although the offer invited acceptance by silence and the offeree was silent, the offeror could not insist that silence would be acceptance. (Hobbs) k. The offer required notice of acceptance, and the offeree did not provide notice of acceptance. (White, Ever-Tite, International Filter, Cf. Carlill) C. Indefiniteness § 33 1. General Rule: A promise is too indefinite to enforce if the court cannot determine the existence of a breach or the appropriate remedy for a breach. a. Varney v. Ditmars- Ditmars, Δ, promised Varney “a fair share of his profits,” then fired him; Held- terms weren’t reas. certain, no way to determine “fair share,” so unenforceable b. Courts are generally reluctant to find promises too uncertain/indefinite to enforce c. Toys, Inc. v. F.M. Burlington- F.M., Δ, entered lease w/Toys; lease gave option to renew for add’l 5 yrs. to the prevailing rate, no agrmt about new rate; Held- “prevailing rate” was definite and option to renew is enforceable 2. A court may require less definiteness if the Π seeks to enforce the promise by means of promissory estoppel. a. Ordinarily when preliminary negotiations fail, there is no contractual liability. b. Hoffman v. Red Owl Stores- Lukowittz or Red Owl Stores made assurances, which Hoffman acted/ relied upon, but the negotiations failed; Held- there was contractual liability; same amt. of definiteness not required for promissory estoppel III. STATUTES OF FRAUDS A. Definition: Every state has enacted numerous statutes making many different kinds of promises unenforceable unless the promises are evidenced by a signed writing. These statutes are called “statutes of frauds.” B. Purpose: prevent fraud by keeping Πs from falsely claiming Δs made promises (extraordinary promises require extraordinary proof). 1. Unintended consequence- sometimes prevents enforcement of a legitimate promise that would otherwise be enforceable. 6 C. Types of Promises Typically Covered 1. General Rule: The kinds of promises that statutes of frauds require to be evidenced by a signed writing differ from state to state. Many states have in common statutes of frauds covering the following six kinds of promises (“MY LEGS”): -Marriage: a promise the consideration for which is marriage (unless the promise is one of two mutual promises to marriage each other), such as a promise by A to pay $10k to B if B marries C. -Year: A promise that cannot possibly be performed (as opposed to merely terminated) w/in one year, such as a promise by A to employ B for 5 years. -Land: A promise to buy or sell land, such as a promise by A to sell a house to B. Provisions in statutes of frauds dealing with land contracts usually are subject to two exceptions: a. A promise to buy land is enforceable w/o a writing after the seller has conveyed the property. b. Under the “part performance” doctrine, the seller may not assert the statute of frauds as a defense if the buyer has substantially relied on the promise to sell. Most courts have said that merely paying the purchase price is not enough reliance, and typically have required the buyer also to have taken possession, made improvements, or performed substantial other actions. -Executor: A promise by an executor to pay the debts of the decedent’s estate out of the executor’s own pocket, such as a promise by executor A to pay B a debt owed to B by decedent C’s estate. -Goods: A promise to buy or sell goods for a price of $500 or more (subject to exceptions we will study later) such as a promise by A to sell a used computer to B for $800. -Suretyship: A promise made by a surety to a creditor to pay a debt that a debtor owes the creditor, such as a promise by A to pay C a debt that B owes C. D. Requisites of Writing and Signing 1. General Rule: A statute of frauds typically requires the Δ’s promise to be evidenced by (1) a writing that (2) states the essential terms of the promise w/reasonable certainty, and that (3) is signed by the Δ. E. Pattern of Argumentation 1. Π’s Claim: The Δ made a promise and did not keep it. 2. Δ’s Defenses: The promise is not enforceable b/c it falls w/in the scope of a statute of frauds and the requisites of writing and signing have not been met. For example, there was no writing, or the writing does not state the essential terms, or the Δ did not sign the writing. 3. Π’s Responses: a. This promise actually does not fall w/in the scope of any statute of frauds. i. For example, the promise does meet the definition of a suretyship promise. Langman v. Alumni Ass’n- UVA Alum. Assoc., Δ, acceded to a “gift” (property) from Langman, Π, and other donors & then refused to pay its debts; Held- was not a suretyship agrmt b/c AA received a direct benefit & was not merely a guarantor ii. Or the promise in fact could be completely performed w/in a year. Coan v. Orsinger- ? can’t find in book b. The Δ is equitably estopped from denying the existence of a sufficient signed writing b/c the Δ asserted that a sufficient signed writing had been made, and the Π relied on the Δ’s assertion. 7 c. Pursuant to the “part performance” exception for land contracts, the Δ may not assert the statute of frauds as a defense b/c the Δ promised to convey land, and the Π substantially relied on the promise. (Johnson Farms) i. Richard v. Richard- oral promise to sell house, couple made improvements, began payments, and continued possession; Held- contract enforced d. The Δ may not assert the statute of frauds as a defense b/c the Π relied on the Δ’s promise, and injustice can be avoided only by enforcement of the promise. Note: Not all courts recognize this defense. Promissory estoppel, § 139 i. Monarco v. Lo Greco- son, Christie, Π, relied on oral promise by rents to devise property, stayed and worked, but father changed mind, leaving property to grandson; Held- unconscionable injury to Christie and Natale unjustly enriched if not enforced ii. § 375- Π can recover if Π has conferred benefit on Δ, which wld allow unjust enrichmt IV. STATUS, INDUCEMENT, AND SUBSTANCE A. Rules Making Certain Promises Unenforceable 1. Infancy- A promise made by a person under the age of majority (in most states, 18 yrs.) is voidable until a reasonable time after the person reaches the age of majority. a. Kiefer v. Fred Howe Motors- Kiefer bought a car when 20, sued to recover the price, wanted court to adopt rule that emancipated minor over 18yrs. is legally responsble for his contracts; Held- propose it to the legislature, they should be the one to make the change 2. Mental Infirmity a. Traditional Test- A promise by a person who, by reason of mental infirmity, cannot understand the nature and consequence of the transaction is voidable. § 15(1)(a) i. Cundick v. Broadbent- Cundick, Π sheep rancher, sold ranch to Broadbent underpriced, Π’s wife, guardian ad litem sued for rescindance based on mental incompetence; Held- Cundick not overreached, wife participated in contract, family never intervened b. Modern Test- In a few states, a promise by a person, who by reason of mental infirmity, cannot act in a reasonable manner in respect to the transaction is voidable, provided that the promisee has notice of the person’s condition. Courts that accept this also accept traditional test. § 15(1)(b) i. Ortelere v.Teachers’ Retirement Board- Ortelere, on leave from school system for mental illness, changed account, leaving husband w/o benefits, then died right after; Held- the system should have been aware of her condition, voidable 3. Public Policy- If enforcement is outweighed by public policy against enforcement, the contract will be held void (§ 178(1)). I.e., a court will not enforce a promise to commit a crime or tort. The public policies of each state may differ. a. Black v. Bush Industries- Black, Π- Bush had not delivered items; Bush- agreemt violates pub. policy b/c Black would be getting excessive profit from U.S. gvmt.; Heldenforceable, court won’t price control, gvmt avoid paying excessive prices by negotiation b. O’Callaghan v. Waller & Beckwith Realty- traditional view (concerned w/3rd parties, not injuries to individual parties); O’C, tenant, Π, injured crossing courtyard, Δ’s defense: exculpatory clause; Held- no violation of public policy; housing shortage temporary, don’t want rule based on temp. condition; freedom to contract, exculpat. contract = cheaper rent c. Henningsen v. Bloomfield Motors- alternative view: Henn., Π, bought new car steering wheel stopped working, Mrs. sev. injured; Held- clause excluding liability from anything but replacement of parts violates pub. policy- grossly unfair; goal- protect consumers 8 4. Duress- a promise induced by an improper threat that leaves the promise w/no reasonable alternative is voidable. Improper threats include threats to commit crimes or torts and threats to break existing contracts in bad faith. § 176 5. Modification w/o Consideration- The “Pre-Existing Duty Rule” says duties under existing contracts cannot serve as consideration for new promises. a. A promise by one party to modify an existing contract by unilaterally assuming additional duties lacks consideration and is not enforceable. i. Alaska Packers’ Ass’n v. Domenico- sailors/fishermen demanded higher pay or quit working, impossible to get substitutes, superint. agreed; Held- new contract w/o consideration; can’t demand add’l compensation for something already obligated to do b. The Pre-Existing Duty Rule does not apply if the parties cancel their existing contract and then form a new contract. i. Schwartzreichv. Bauman-Basch- Sch., Π, clothing designer agreed to work for BB, higher offer from other co., so B-B offered him more to reject the other, he began working for B-B, then fired; Held- rescission followed by new agreement binding contract; tore off sig.s on old contract- clearly cancelled; new agreement is binding c. Some courts will enforce promises to modify contracts w/o consideration if the modification is fair and reasonable in light of changed circumstances. i. Watkins & Sons v. Carrig- Π excavating cellar for stated price, finds solid rock, new agreement of 9x greater payment; Held- Δ Carrig intentionally yielded to higher price w/o protest (relinquished his rights), should be held to the new contract 6. Fraudulent or Material Misrepresentation- A misrepresentation is a statement of fact (as opposed to mere opinion) that is not true. A promise induced by a fraudulent or material misrepresentation, upon which the promise justifiability relied, is voidable. 7. Active Concealment- A promise induced by an action intended to prevent the promisor from learning a fact is voidable to the same extent a promise induced by a misrepresentation of the fact would be voidable. 8. Non-Disclosure of Facts in Special Circumstances a. In general, a promise is not voidable merely b/c the promise failed to disclose facts to the promisor. i. Swinton v. Whitinsville Savings Bank - Δ, Bank, sold Swinton, Π, family house infested w/termites, which Δ knew; Held- no misrepresentation (just bare non-discl.), b/c Swinton never asked; no discl. rule- too idealistic to expect; Swinton can’t rescind b. A promise may be voidable if it is induced by a half-truth, where the promise misleads the promisor by disclosing some of the facts but not all the facts. i. Kannavos v. Annino- Annino, Δ, converted house into multi-fam. dwelling w/8 apts., violating city zoning, advertised it as investment property, sold house to Kannavos (unaware of zoning violation); Held- Kannavos can rescind b/c Δs were deceptive c. A promise may also be voidable if it is induced by a non-disclosure of facts where the promisor and promise can expect full disclosure based on their “confidential” relationship (§ 161d) or when it is required by statute (i.e. lawyer might have to make full disclosure to a client). 9. Mutual Mistake a. A mistake is an incorrect belief about what the facts currently are, as opposed to a poor prediction about what the facts later might turn out to be. b. A promise induced by a mutual mistake as to a basic assumption that has a material effect is voidable, unless the promisor for some reason bore the risk of mistake. 9 i. Sherwood v. Walker- Walker, Δ, agreed to sell cow to Sherwood, which they thought was sterile, discovered cow pregnant, Δ refused to deliver cow; Held- contract is voidable; cow not the animal they intended to exchange; barren very diff from preg. ii. Cf. Wood v. Boynton- Π asked jeweler what a stone was worth, he didn’t know, she sold it for $1, later determined to be worth $700; Held- dismissed, no ground for recov.; Wood bears risk of mistake, not voidable iii. Stees v. Leonard- Δs failed to complete bldg on Π’s lot, fell 2x b/c soil was quicksand; Held- gen. principle- if man binds himself by contract, he must perform despite any hindrance; necessary to drain land, so Δs should have 10. Unilateral Mistake- In some states, a promise induced by a unilateral mistake of the promisor is voidable if enforcement would make the contract unconscionable. 11. Unconscionability- A court may refuse to enforce a term of contract, or the complete contract, if the court finds that the term or the contract was unconscionable at the time the contract was made. B. Unenforceability as a Defense or a Basis for Rescission 1. General Rule- A person who has made a promise that is unenforceable under one of the preceding rules may assert the rule as a defense or as a basis for rescission. 2. Basic patterns of argumentation: a. Unenforceability as a Defense: i. Π’s Claim: The Δ made a promise and did not keep it. (E.g., “Walker promised to sell Rose the Cow and then refused to convey her.”) ii. Δ’s Defense: The promise is not enforceable under one of the rules stated above. (E.g. “The promise is not enforceable b/c it was induced by our mutual mistake that Rose the Cow was sterile.”) b. Unenforceability as a Basis for Recission: i. Π’s Claim: The court should rescind the contract and restore the status quo b/c my promise was unenforceable under one of the rules stated above. (E.g., “The court should rescind my promise to pay Fred Howe Motors for a car, ordering Fred Howe Motors to return my money, b/c I was an infant at the time that I made the promise.”) C. Restitution Upon Rescission 1. General Rule: To obtain an equitable remedy like rescission, a Π must do that which is equitable. Accordingly, a Π seeking to rescind a contract often first must make a restitution of any benefit conferred by the Δ. However, a court will not require a Π to make restitution in situations where justice does not require it. 2. Examples: An infant generally must make restitution when rescinding a contract based on infancy. But a court will not require an infant to make restitution if the subject matter of the contract is no longer available. a. One exception is that an emancipated infant must make restitution for necessaries conferred by the Δ even if the subject matter no longer is available. D. Form Contracts 1. Definition: Promises made on pre-printed forms often are called “form contracts.” If the party who prepared the form refuses to agree to any changes in the form’s terms, the form often is called a “contract of adhesion.” 2. General Rule: For the most part, promises made in form contracts are treated like other promises. A party may enforce a promise in a form contract, even if it is a contract of adhesion, provided the party can show offer, acceptance, consideration, and compliance 10 w/any applicable statute of frauds, and the promise is not unenforceable for any of the above reasons. 3. Special Rules: a. Adequate Notice- A person does not assent to terms printed on a form if the person did not have reason to know that the form contained contractual terms. i. Klar v. H & M Parcel- man checked furs worth $1k at H & M, they lost it, Δ- receipt had contractual terms, not liable for any damages over $25; Held- he was not bound by the terms b/c he didn’t see it as a contract, just a way to identify his package b. Strict Construction- In choosing among reasonable meanings for terms in a form contract, courts will select meanings that disfavor the person who drafted the form. i. Galligan v. Arovitch- Galligan, Π, tenant, injured crossing courtyard; exculpatory clause did not specifically mention grass, just sidewalks; Held- court strictly construed the exculpatory clause to not exclude liability for injuries from courtyard c. Public Policy and Unconscionability- Courts are more likely to invalidate terms on grounds of public policy or unconscionability in adhesion contracts than in other types of contracts. (Henningsen v. Bloomfield Motors) i. But see O’Callaghan v. Waller & Beckwith Realty- p. 8 4. Pattern of Argumentation: A Π may sue to enforce a form contract, arguing the Δ breached a promise Δ made in the form. In many cases, the reverse- Δ wishes to rely on form contract for a defense. Our cases had the following patter of argumentation: a. Π’s Claim: The Δ breached a contract or committed a tort. b. Δ’s Defense: I am not liable, or my liability is limited, b/c of an exculpation clause in our form contract. c. Π’s Replies: i. The form contract is not enforceable b/c I did not have adequate notice that the form contained contractual terms. (Klar) ii. The exculpation clause, when strictly construed, should be interpreted to mean X, and it therefore does not apply to this situation. (Galligan) iii. The exculpation clause is unenforceable b/c it violates a strong public policy against X. (Henningsen v. Bloomfield Motors) iv. The exculpation clause is unenforceable on grounds of unconscionability b/c X (term is grossly unfair). V. REMEDIES A. Specific Performance 1. Definition: A court grants the remedy of specific performance by ordering the Δ to carry out the promise that the Δ made. 2. Limitations: A court may deny specific performance for a variety of reasons. For example: a. Damages would be adequate. A court will deny specific performance if damages would be an adequate remedy. i. In determining adequacy, courts consider whether damages can be proved w/reasonable certainty, whether Π might obtain a substitute performance, and whether Π could collect an award of damages. ii. By tradition, courts have held that damages are not an adequate remedy for a breach of a contract to sell land (or if unique goods). b. The bargain was unfair. A court will deny specific performance if, at the time the contract was made, the terms of the contract were unfair or the consideration for the Δ’s promise was grossly inadequate. 11 B. Expectation Damages § 344(a), 347 (formula) Expectation = loss in value [what Δ promised – what Δ delivered] + other loss – costs avoided (costs Π expected – costs Π incurred) – other loss avoided 1. General Rule: The Π has a right to “expectation damages,” which is the amt. of money necessary to put the Π in the position the Π would have been in had the Δ not breached the contract. Expectation damages = Π’s “loss in value” + “other loss” – the Π’s “costs avoided” and – “other loss avoided.” 2. Definitions: a. “Loss in value”- different btw what Δ promised and what Δ delivered i. i.e. In Parker v. 20th Century Fox, the loss in value was $750k b/c Fox promised to pay Parker $750k and actually paid her nothing. b. “Other Loss” includes any consequential or incidental harm caused by Δ’s breach. i. i.e. in Hadley v. Baxendale, the other loss was the profit lost while the factory was shut down b/c of the delay in delivering the mill shaft. c. “Cost Avoided”- the difference btw the cost Π expected in performing and the cost the Π actually incurred. i. i.e. in Sullivan v. O’Connor, the cost avoided was zero b/c Mrs. Sullivan expect to pay Dr. O’Connor’s fee and she paid the fee. Sullivan wanted nose job, 3 unsuccessful operations (when orig. would only be 2), looked worse. She recovered on basis of reliance, damages for pain/suffering in 3rd op., and disfigurement. d. “Other Loss Avoided”- any losses that would have been incurred incident to, or as a consequent of, the Π’s performance but which were not incurred b/c of the breach. i. i.e., in Sullivan v. O’Connor, the other loss avoided was zero, b/c Mrs. Sullivan expected to undergo 2 operations and pay the hospital fees incident to her performance, and she did those things. 3. Limitations: a. Avoidability- Π may not recover damages that could be avoided w/o undue risk, burden, or humiliation. Efficient- every excess damage incurred will be spent in costs. § 350 i. Rockingham County v. Luten Bridge- Rockingham Cty. hired Luten to build a bridge, breached and told Luten to stop working, Luten built it anyway; Held- Luten should have stopped and avoided further costs (inefficient- inflicting damages w/o increasing benefit); Π can’t hold Δ liable for unnecessary damages ii. The Π may have to make substitute arrangement, such as undertaking comparable employment. Cf. Parker v. 20th century Fox- MacLain contracted to make a musical, Fox breached, offering McL a western instead. Held- western not a comparable substitute, she gets paid for constructive service (labor she would have expended) b. Incomplete or Defective Performance- Ordinarily, Π ought to be able to get loss in value to Π. Sometimes loss in value to Π impossible to prove, but Π can always recover the loss in market value. § 348(2) i. As an alternative, the Π may recover the cost to complete or remedy the defect unless that cost is grossly disproportionate to the probable loss in value to the Π. 12 Jacobs & Youngs v. Kent- Kent, Δ, wanted house built w/Reading pipe, got Cohoes instead, refused to pay last installment; Held- J & Y can recover; Kent can’t get cost of remedy- grossly disproportionate, loss in value is negligible (maj. view) Peevyhouse v. Garland Coal- family farm rented for coal retrieval; ground left uneven; Court followed J & Y case, not Groves; Held- loss in market value ($300), not cost to remedy (29k), is the limit of damages Rest.- giving the person the money it would cost to complete remedy would put them in a better position than they would have been in; they won’t use it for repair But see Groves v. John Wunder- (minority view) Groves leases land and use of gravel/sand to Wunder, Δ; Δ promised rent and leave property at uniform grade, which it didn’t; Held- Π not limited to loss in market value, even tho cost to remedy (60k) vs. market value (12k) disprop.; different b/c willful breach; incentive arg. c. Unforeseeability- Π may not recover damages for losses that were not foreseeable at the time the contract was made. § 351 i. Losses are foreseeable if they arise in the ordinary course of events (general/ direct and incidental damages) or if the Δ has notice of the special circumstances giving rise to them (special/ consequential damages). Hadley v. Baxendale- Hadleys, Π, ran flour mill, shaft broke, asked Δs to ship part in 1 day to be used as a model; took 6 days, loss of profits b/c mill shut down 5 add’l days; Held- Δs, no way of knowing; can’t recover unforeseeable damages d. Uncertainty- Π cannot recover damages that the Π cannot prove w/reasonable certainty. i. Kinds of uncertainty: fact of loss (did breach harm Π?): Collatz; Extent of loss (difficult to determine extent): Fera, Hadley; Value of loss (difficult to put $ figure on it); Altern. Remedies (nominal, reliance, specific per., liquidated). ii. Collatz v. Fox Wisconsin Amusements- Collatz, Π, one of 2 contestants left, both got question wrong, Coll. 1st to get it wrong- arbitrarily eliminated; Held- can’t prove w/reas. certainty he suffered loss b/c he may not have won iii. Fera v. Village Plaza- Fera bros. opening wine/liquor store, V-P went bankrupt, taken over by bank, lease misplaced and loc. leased to someone else; Held- no history, tho proof of damages difficult issue, jury could have reas. found damages legit. C. Reliance Damages § 344(b), 349 1. General Rule- as an alternative to expectation damages, the Π may recover reliance damages which is the amount of money necessary to put the Π in the same position the Π would have been in if the contract had not been made. D. Nominal Damages § 346(2) 1. General Rule- If the Π proves the Δ breached the contract, but cannot prove the damages, a court may award the Π nominal damages (traditionally, $1 or 6 cents) E. Liquidated Damages § 356 1. General Rule- the court may award the Π liquidated damages, which are damages that the parties stipulated in the contract 2. Limitations: a. Penalties- A court will not enforce a stipulated measure of damages that is unreasonably large in comparison to actual or anticipated loss i. Cf. Dave Gustafson v. State- Gustafson hired to pave a road for the state, contract had stipulated damages of $210/day for late completion, Dave was late by 67 days, and the state w/held payment of $14,070; Held- enforceable, reasonable amount 13 b. Unconscionability- A court will not enforce a stipulated remedy that is unconscionably small. (Cf. Henningsen v. Bloomfield Motors - i.e. remedy where all Mrs. Henningsen got was a new steering wheel) F. Pattern of Argumentation 1. Π’s Claim: The Δ made a promise and did not keep it. 2. 1st Possible Remedy: Liquidated Damages- if the promise is enforceable, the court should order the Δ to pay the amount of damages stipulated in the contract 3. Δ’s Reply: Penalty- the liquidated damage measure is unreasonably large in relation to both actual and anticipated damages and therefore cannot be enforced as a penalty. 4. 2nd Possible Remedy: Specific Performance- If liquidated damages are not available, the court should order specific performance of the Δ’s promise. 5. Δ’s Replies: a. Damages are adequate. Π is not entitled to specific performance b/c damages would be an adequate remedy. b. Bargain was unfair. Π is not entitled to specific performance b/c the bargain was unfair at the time it was made. i. McKinnon v. Benedict- McKinnon, Π, loaned Benedicts $ to buy campground prop. adjacent to him, business help; Δs promised not to build on campground in Πs direction; Held- unfair transaction, denied spec. perf. b/c denial of equitable remedies ii. Tuckwiller v. Tuckwiller- Morrison made contract w/niece to care for her in exchange for house/property, she died very soon after; Held- specific perf. enforceable; unfair? look at exchange time transaction was made, didn’t know how long she’d live 6. 3rd Possible Remedy: Expectation Damages- If specific performance is unavailable, the Δ should pay expectation damages. a. Δ’s breach has made me worse off b/c [describe “loss in value” plus “other loss”], although I admit that I am better off b/c [describe “costs avoided” plus “other loss avoided”]. b. Expectation damages equal the difference btw these two figures. 7. Δ’s Replies: a. Avoidability- the court should reduce the expectation damages claimed based on avoidability. i. The Π has overstated the “other loss” b/c some of that loss could have been avoided. ii. The Π also has understated the “costs avoided” b/c the Π could have avoided some additional costs. (Rockingham County; Parker) b. Incomplete or Defective Performance- the court should reduce the expectation damages claimed for an incomplete or defective performance i. For “loss in value,” the Π has attempted to use the cost to complete or remedy, but this amount is grossly disproportionate to the probable loss in value to the Π. (Jacob & Youngs; Peeveyhouse; But see Groves v. John Wunder ) c. Unforseeability- the court should reduce the expectation damages claimed b/c the “loss in value” was not foreseeable at the time the contract was made b/c the damages did not arise in the ordinary course of events and I had no notice of the special circumstances giving rise to the damages (Hadley) d. Uncertainty- the court should reduce the expectation damages claimed b/c the Π cannot prove the “loss in value” or “other loss” w/reasonable certainty.(Collatz v. Fox Wisconsin Amusements ; Cf. Fera v. Village Plaza) 14 8. 4th Possible Remedy: Reliance Damages- if expectation damages are not available, the Δ should pay reliance damages. I am worse off than if the contract had never been made b/c [state reasons]. 9. 5th Possible Remedy: Nominal Damages- If no other remedy is available, the Δ at least should pay nominal damages. 15