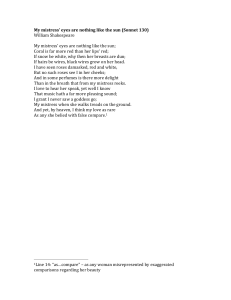

Sonnet CXXX

advertisement

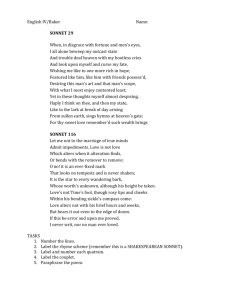

Sonnet by William Shakespeare Presentation by Adriana Pequeno April 30, 2012 The word sonnet comes from the Italian word sonneto, meaning “little song”. Petrarch, an Italian Poet, used a Problem-Solution format in his sonnets (octave presents the problem and the sestet solves it.) 14 lines Divisions – 3 quatrains and 1 couplet Distinguished rhyme scheme – abab cdcd efef gg Meter or rhythm - iambic pentameter Often concerned with a romantic theme (love of a man for a woman) Quatrain 1 – introduces the subject Quatrains 2 – 3 further develop the subject or introduce a conflict Concluding Couplet – Offers a solution/ comment/ summary Defining Unfamiliar Terms in Sonnet CXXX Coral – reddish yellow; skeletons forming reefs (very colorful) Dun – dark and gloomy Damask’d - a common name for R. damascena, a large, hardy rose that grows up to 8 feet, with fragrant double pink to red flowers. My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun; Coral is far more red than her lips' red; If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun; If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head. I have seen roses damask'd, red and white, But no such roses see I in her cheeks; And in some perfumes is there more delight Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks. I love to hear her speak, yet well I know That music hath a far more pleasing sound; I grant I never saw a goddess go; My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground: And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare As any she belied with false compare. Subject – woman or female lover Seems the speaker is complaining about his mistress’s physical features. Does so by comparing her to nature’s beauty She’s nothing like the “sun,” (1) that’s for sure. In Romeo and Juliet, Juliet is compared to the sun. Seems like the red of the woman’s lips are much, much duller than “coral” (2). Woman’s “breasts” (3) are dark and gloomy. Speaker uses unflattering diction, e.g., “black wires,” (4) to describe the woman’s hair. The speaker’s mistress’s cheeks seem dull compared to the fine beauty he has witnessed in “roses damask’d” (5-6). It seems that the speaker takes greater pleasure in the “perfumes” offered by nature than in the foul scent his lady exudes (7-8). The speaker’s unflattering diction, e.g., “reeks,” when describing his mistress’s breath can easily make the reader turn away with disgust. It seems the speaker doesn’t think highly of his mistress’s physical characteristics. The speaker seems really conflicted about his mistress in this quatrain. First, he does state how he loves “to hear her [his mistress] speak” (9). Then he offers how “music” itself is more pleasing to the ear than his mistress’s voice (10). Speaker seems rather ambivalent about his mistress. Speaker’s mistress is certainly not a “goddess” since she “treads” rather heavily it seems on the “ground” (9-10). A goddess would gracefully float from one place to another while an earth bound woman would “walk” rather heavily and awkwardly. Using the word “tread” to describe the way his mistress walks again suggests that his mistress is quite unattractive/ungraceful. The conjunction “yet” that begins the closing couplet suggests a sort of turn in the speaker’s perspective of his mistress. He realizes why he loves her; she is “rare” (11). The reader, however, is left to wonder what rarities the mistress does possess. There’s the mystery. Regardless, the reader knows that the speaker loves not his mistress’s physical qualities, but something else that is often overlooked and usually considered to be unimportant. The speaker also calls his mistress, “my love,” which also may indicate that he is in love with her (13). Interestingly, the speaker sets his mistress against all of the other rare females who are so often falsely described as possessing rich beauty beyond compare (13-14). Seems like the poem is a bit of a joke. Metaphor – “If hairs be wires” (4). Speaker is comparing the mistress’s hairs to very unappealing wires. Diction – “dun,” “wires,” “reeks,” “treads,” and “ground” (3-4, 8, 12). Speaker uses such unflattering language to emphasize how very unattractive his mistress is. Hyperbole – “black wires grow on her head” (4). Speaker seems to really exaggerate the poor quality of his mistress’s hair Parody – by writing this sonnet, the speaker seems to be mocking the sonnet’s true intention – instead of glorifying his mistress with highly stylistic or ornate language, the speaker uses plain language to describe his mistress and, in the end, he ironically still loves her. This sonnet, in many ways, mocks what the sonnet is supposed to represent: a serious piece of writing. 5 Beauty Within is Greater than Beauty Without Physically, the speaker does not describe his mistress in the most favorable light, but he is nevertheless in love with her. Her inner worth, one can infer, somehow trumps her physical appearance. This is how she continues to win the speaker’s heart. 5 Inner Mystery 10 Description : Mysterious How the Picture Connects with the Poem: Well, the picture here is quite unclear.. It’s hard to identify its subject and, therefore, it remains a mystery. Regarding the sonnet, the reader realizes that the speaker is not in love with his mistress’s physical qualities, but her inner qualities, qualities that still remain a mystery at the conclusion of the poem. Highly recommended Departure from the typical sonnet’s true intention Language is humorous. Easy to read – though still very powerful. Great message to the reader is provided. 7 Defined the Petrarchan sonnet Defined the Shakespearean sonnet Provided a Definitions List Provided an analysis of each quatrain and the final couplet that make up Sonnet CXXX Covered literary elements Discussed a major theme Provided an image Provided a recommendation Recited the poem 11 My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun; Coral is far more red than her lips' red; If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun; If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head. I have seen roses damask'd, red and white, But no such roses see I in her cheeks; And in some perfumes is there more delight Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks. I love to hear her speak, yet well I know That music hath a far more pleasing sound; I grant I never saw a goddess go; My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground: And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare As any she belied with false compare.