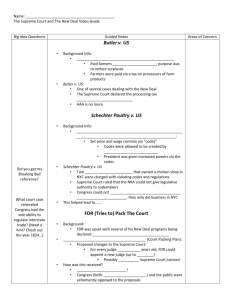

Facts of the Case

advertisement

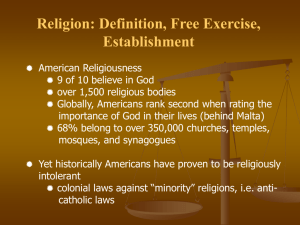

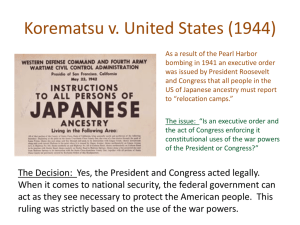

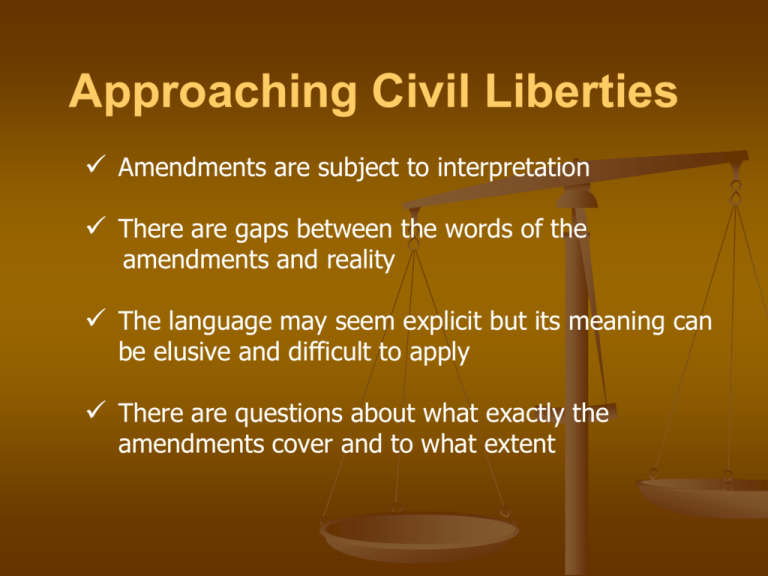

Approaching Civil Liberties Amendments are subject to interpretation There are gaps between the words of the amendments and reality The language may seem explicit but its meaning can be elusive and difficult to apply There are questions about what exactly the amendments cover and to what extent Rise of Civil Liberties cases at the Supreme Court Since the late 1930, the justices have contributed to this United States v. Carolene Products (1938) Palko v. Connecticut (1937) (previously seen) Murdock v. Pennsylvania (1943) Courts presumption that most laws are constitutional Preferred freedoms doctrine signals the Courts willingness to give closer scrutiny to civil liberties and rights disputes Increased use of litigation by Issue Advocates and Interest Groups, leading to a “rights revolution” Growth in number of cases among other nations United States v. Carolene Products Advocates Docket: 640 Citation: 304 U.S. 144 (1938) Appellant: United States Appellee: Carolene Products Abstract Oral Argument: April 6, 1938 Decision: April 25, 1938 Issues: an economic regulation dispute, not civil liberties Categories: “preferred freedoms” Facts of the Case A 1923 act of Congress banned the interstate shipment of "filled milk" (milk with skimmed milk and vegetable oil added). A manufacturer, indicted for shipping filled milk, challenged the law arguing the law was unconstitutional on both Commerce Clause and due process grounds. Question Does the Filled Milk Act of Congress of March 4, 1923, violate the Commerce Power granted to Congress in Article 1 Section 8 and the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment? Conclusion The Court upheld the act. In this case, the Court planted the seeds for a new jurisprudence in a footnote to Stone's opinion for the Court. Here Stone gives a presumption of constitutionality to economic regulation. The Court would no longer substitute its views on economic policy for the views of Congress. Stone went further in footnote four by cautiously asserting that certain types of legislation might not merit deference toward constitutional validity. The most controversial element in the footnote was the suggestion that prejudice directed against discrete and insular minorities may call for "more searching judicial inquiry." Murdock v. Pennsylvania Advocates Docket: Citation: 319 U.S. 105 (1943) Appellant: Murdock, a Jehovah's Witness Appellee: The borough of Jeanette, Commonwealth of PA Abstract Oral Argument: March 10, 11, 1943 Decision: May 3, 1943 Issues: Freedom of Religion: Free Exercise Categories: “preferred freedoms” Facts of the Case The borough of Jeanette, Pennsylvania had an ordinance requiring solicitors to purchase a license from the borough. Murdock, a Jehovah’s Witness, asked for contributions in exchange for books and pamphlets. The city claimed that this meant that they were being sold and a license was required. Question Did the licensing requirement constitute a tax on Murdock’s religious exercise. Conclusion The Court in a 6-3 decision determined that the ordinance was an unconstitutional tax on the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ right to freely exercise their religion. Significance: the neutral imposition of the tax on solicitation performed by a religious group did not make it constitutionally acceptable. Also, the Court distinguished between commercial activity and religious activity that involves the selling of religious literature. The "Jehovah's Witnesses cases" Of the 72 cases brought by the Jehovah's Witnesses before the U.S. Supreme Court, these four are known as the "Jehovah's Witnesses cases" because the decisions for all four were handed down by the US Supreme Court on May 3, 1943: 1. Jones v. Opelika (1942), the Court upheld a statute prohibiting the selling of literature without a license because it only covered individuals engaged in a commercial activity rather than a religious ritual. The freedom of press was not to be restricted only to those who can afford to pay the licensing fee. 2. Murdock v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (319 US 105) 3. Martin v. City of Struthers (319 US 141), the Court invalidated a city ordinance from Struthers, OH forbidding knocking on doors/ringing bells to distribute "handbills, circulars or other advertisements." 4. Douglas v. City of Jeannette, PA the Court upheld the jurisdiction of the District Court to proceed with criminal prosecutions of 21 Jehovah's Witnesses arrested in Jeannette for selling books during a Witness "Watch Tower Campaign" in 1939. License Requirement for Literature Distribution / Parade & Park Permit 1. Lovell v. City of Griffin (1938), the Supreme Court ruled it was not constitutional for a city to require written permission from the City Manager to distribute religious material. 2. Schneider v. New Jersey (1939), the Supreme Court invalidated an ordinance that provided: "No person ... shall canvass, solicit, distribute circulars, or other matter, or call from house to house ... without first having reported to and received a written permit from the Chief of Police." 3. Cantwell v. Connecticut (1940), the Court ruled that the statute requiring a license to solicit for religious purposes was a restraint that vested the state with excessive power in determining which groups must obtain a license. License Requirement for Literature Distribution / Parade & Park Permit 4. Cox v. New Hampshire (1941), the Court unanimously upheld the convictions of Jehovah's Witnesses for engaging in a public parade without a license. The Court ruled that, although the government cannot regulate the contents of speech, it can place reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions on speech for the public safety. 5. 6. 7. 8. Jones v. Opelika II (1942) Jones v. Opelika II (1943) Douglas v. City of Jeannette (1943) Murdock v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (1943) 9. Follett v. Town of McCormick (1944), the Court held that people who earn their living by selling or distributing religious materials should not be required to pay the same licensing fees and taxes as are expected of those who sell or distribute non-religious materials. 10. Watchtower Society v. Village of Stratton (2002), Civil Liberties Amendment I Freedom of Expressions (previously covered) Amendment II A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed. Amendment I, III, IV, V, IX Right to Privacy Amendments that imply Right to Privacy: I - Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances. III - No Soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law. IV - The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized. Amendments that imply Right to Privacy: V - No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation. IX - The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people. Religion: Definition, Free Exercise, Establishment American Religiousness 9 of 10 believe in God over 1,500 religious bodies Globally, Americans rank second when rating the importance of God in their lives (behind Malta) 68% belong to over 350,000 churches, temples, mosques, and synagogues Yet historically Americans have proven to be religiously intolerant colonial laws against “minority” religions, i.e. anticatholic laws Religion: Definition, Free Exercise, Establishment Yet historically Americans have proven to be religiously intolerant (continued) 11 of 13 states had some restrictive laws (only Maryland and Rhode Island provided full religious freedom) 6 states had established religions some states imposed religious oaths on public officials Anti-federalists objected the lack of any guarantees of religious liberty Religion: Definition, Free Exercise, Establishment Breaks with past trends Constitutional Convention delegates opposed Ben Franklin’s proposal for prayer before debates Article VI provides for oaths by government officials to defend the constitution but no religious tests requirements for public office Defining Religion – Three Supreme Court cases 1. Reynolds v. United States (1879) 2. United States v. Ballard (1944) 3. United States v. Seeger (1965) Reynolds v. United States Advocates Docket: Citation: 98 U.S. 145 (1879) Appellant: George Reynolds Appellee: United States Abstract Oral Argument: November 14-15, 1878 Decision: May 5, 1879 Issues: Categories: Facts of the Case George Reynolds was a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, charged with bigamy after marrying Amelia Jane Schofield while still married to Mary Ann Tuddenham in the Utah Territory. Question Does the? Conclusion The Supreme Court upheld the conviction finding Reynolds guilty. The constitution does not define religion, so to reach a ruling Court investigated the history of religious freedom in the United States. The court quoted a letter from Thomas Jefferson in which he stated that there was a distinction between religious belief and action that flowed from religious belief. Belief "lies solely between man and his God," therefore "the legislative powers of the government reach actions only, and not opinions." The court argued that if polygamy was allowed, how long before someone argued that human sacrifice was a necessary part of their religion, and "to permit this would be to make the professed doctrines of religious belief superior to the law of the land, and in effect to permit every citizen to become a law unto himself." The Court believed the true spirit of the First Amendment was that Congress could not legislate against opinion but could legislate against action. Advocates United States v. Ballard Docket: Citation: U.S. (1944) Appellant: United States Appellee: Guy Ballard Abstract Oral Argument: Decision: Issues: Categories: Facts of the Case Guy Ballard was convicted of using and conspiring to use mails to defraud. He was a follower of the 'I Am' movement and believed that the words of St. Germain, the divine messenger, were transmitted through him. Ballard also claimed to possess the power to heal people and claimed to have had success in doing so in the past. He solicited contributions via mail in exchange for offering his healing abilities. The government asserted that he 'well knew' that these claims were false and he used them to defraud others of their money. In the initial trial, the jury was told not to consider Ballard's religious beliefs, instead they were merely to determine whether the defendant believed that he possessed the ability to heal others. Question Does the Fifth Amendment? Conclusion The Court ruled that it was proper for the jury to base its decision on the sincerity of Ballard's beliefs. Justice Douglas, authoring the majority opinion, wrote: “The content of the teachings of the 'I Am' movement were immaterial. These beliefs could not be an issue in any case because the content of religious convictions could not be judged as either correct or incorrect. Because of the First Amendment, heresy is an unknown offense in the United States. All that mattered was whether Ballard believed in good faith that he possessed the powers he claimed to have. If this was so, then he must be acquitted.” United States v. Seeger Advocates Docket: Citation: 380 U.S. 163 (1965) Appellant: United States Appellee: Daniel A. Seeger Abstract Oral Argument: Decision: Issues: Categories: Facts of the Case This case involved the application of the Universal Military Training and Service Act which exempted people from military service if their religious training or belief makes them opposed to such service. It defined appropriate training or belief as an individual's belief in a relation to a Supreme Being involving duties superior to those arising from any human relation, but [not including] essentially political, sociological, or philosophical views or a merely personal moral code." One person involved in the suit believed in a “supreme reality” while another believed in a “universal reality.” Neither of these were included in the class of beliefs covered by the Act. They claimed that the law unfairly did not exempt nonreligious conscientious objectors and that it discriminated between different forms of religious beliefs. Question Conclusion In a unanimous opinion, the Court allowed those people with general theistic belief systems to be declared conscientious objectors. Advocates City of Boerne v. Flores Docket: 95-2074 Citation: 521 U.S. 507 (1997) Appellant: p Appellee: o Abstract Walter E. Dellinger, III (Argued the cause for the Federal respondent) Marci A. Hamilton (Argued the cause for the petitioner) Douglas Laycock (Argued the cause for the respondent Flores) Jeffrey S. Sutton (Argued the cause on behalf of Ohio et al., as amici curiae, support the petitioner) Oral Argument: Wednesday, February 19, 1997 Decision: Wednesday, June 25, 1997 Issues: First Amendment, Free Exercise of Religion Categories: Facts of the Case The Archbishop of San Antonio sued local zoning authorities for violating his rights under the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), by denying him a permit to expand his church in Boerne, Texas. Boerne's zoning authorities argued that the Archbishop's church was located in a historic preservation district governed by an ordinance forbidding new construction, and that the RFRA was unconstitutional insofar as it sought to override this local preservation ordinance. On appeal from the Fifth Circuit's reversal of a District Court's finding against Archbishop Flores, the Court granted Boerne's request for certiorari. Question Did Congress exceed its Fourteenth Amendment enforcement powers by enacting the RFRA which, in part, subjected local ordinances to federal regulation? Conclusion Yes. Under the RFRA, the government is prohibited from "substantially burden[ing]" religion's free exercise unless it must do so to further a compelling government interest, and, even then, it may only impose the least restrictive burden. The Court held that while Congress may enact such legislation as the RFRA, in an attempt to prevent the abuse of religious freedoms, it may not determine the manner in which states enforce the substance of its legislative restrictions. This, the Court added, is precisely what the RFRA does by overly restricting the states' freedom to enforce its spirit in a manner which they deem most appropriate. With respect to this case, specifically, there was no evidence to suggest that Boerne's historic preservation ordinance favored one religion over another, or that it was based on animus or hostility for free religious exercise. The “establishment clause” a.prohibits the establishment of a state religion. b.provides a wall of separation between church and state. c. was furthered by the Lemon v. Kurtzman decision. d. all of the above. Free Exercise Clause Does a literal interpretation suggest a group may practice any religion it chooses? Is such an interpretation reasonable? What if the religious member engages in dangerous practices, i.e taking hallucinogenic drugs? Should government prohibit religious activities that are dangerous or offensive? The Belief – Action Distinction Based on the Thomas Jefferson letter in 1803 to the Danbury Baptist Association Jefferson believed that free exercise is not absolute and government may regulate religious actions The Supreme Court supported this position in 1940 in Cantwell v. Connecticut, upholding the constitutionality of laws affecting religious practices as long as the legislation serves the nonreligious goal of safeguarding the peace, order, and comfort of the community and is not directed at any particular religion. The Belief – Action Distinction The Court sustained laws prohibiting religiously sanctioned polygamy (the practice of taking multiple wives) in Reynolds v. United States in 1879. The Court sustained laws prohibiting use of peyote during religious services in Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith in 1990. The Belief – Action Distinction By contrast, the Court invalidated a law that forced a Seventh Day Adventist to work on Saturday – her faith’s Sabbath – in order to receive unemployment benefits in Sherbert v. Verner in 1963. The Court also upheld the right of the Amish to withdraw their children from public school before the age of sixteen in Wisconsin v. Yoder in 1972. Congress and Religious Freedom Congress does not always agree with the way the Court interprets the Free Exercise Clause. Recently, Congress has shown greater support for freedom of religious expression than the Supreme Court. Goldman v. Weinberger in 1986 City of Boerne v. Flores in 1997 Congress and Religious Freedom After Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith in 1990, where the Court outlawed the use of peyote in religious ceremonies, Congress expressed renewed concern over the Court’s reasoning in free exercise cases. In 1993, Senators Ted Kennedy and Orrin Hatch led passage of the Religious Freedom and Restoration Act (RFRA). The Court ruled RFRA unconstitutional in City of Boerne v. Flores in 1997 The Supreme Court has limited recitation of prayers in public schools primarily on the basis of. a. the establishment clause. b. the free exercise clause. c. freedom of speech. d. the right to privacy. The Supreme Court maintains that the establishment clause prevents all of the following evils EXCEPT. a. sponsorship b. financial support c. active involvement of the government in religious activity d. accommodating to religious needs The relationship between the state and religion is addressed in a. the clear and present danger clause. b. the establishment clause. c. the free exercise clause. d. both b and c. The “free exercise” clause precludes all of the following EXCEPT. a. a requirement of a religious oath as a condition of public service. b. denying persons certain rights because of their beliefs or lack of them. c. discrimination based on religious belief systems rather than adherence to a formal creed. d. a requirement of a religious oath for public school teachers. The free exercise clause has been interpreted by American courts to mean that a. no conduct motivated by religion is subject to state authority. b. people must keep their opinions about religion to themselves. c. Amish may take their children out of public schools after the eighth grade. d. although religious beliefs cannot be regulated, religious conduct may be.