Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864)

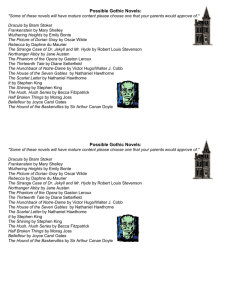

advertisement