What was the impact of the Sino-Japanese War on the Reform

advertisement

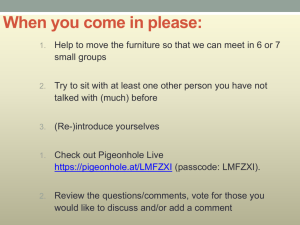

What was the impact of the Sino-Japanese War on the Reform Movement? L/O – To analyse the significance of the Sino-Japanese War and identify the causes & effects of the 100 Days Reform Emperor Guangxu Battle of the Yalu River - 1894 Introduction • The Self-Strengthening Movement had made considerable strides in modernising Qing China but resistance to reforms was still widespread amongst large sections of the population. • With defeat in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95, it became apparent that modernisation needed to be accelerated. • Reform-minded officials and scholars continued to demand reforms, persuading the Emperor Guangxu to back radical reforms to the entire system. Emperor Guangxu Introduction • This resulted in the ‘100 Days Reform’ in 1898. Emperor Guangxu issued a torrent of reform edicts. It was ended by Cixi, who returned from semiretirement and put the Emperor under house arrest. • Led by Cixi, the Qing Court returned to anti-foreign policies, which became heightened as imperial powers began to demand more concessions from China. This in turn sparked the Boxer Uprising of 1899-1900. Empress Dowager Cixi Causes of the Sino-Japanese War • In the 1870s, China was becoming increasingly concerned about growing Japanese influence in Korea, one of its tributary states. • These fears became real in 1876 with the Treaty of Kangwha which gave Japan rich trading concessions throughout Korea. • In the 1882 Imo Incident and 1884 Gapsin Coup, both China and Japan had sent troops to Seoul to put down uprisings against the Korean King. This had nearly led to war. Causes of the Sino-Japanese War • Tensions eased slightly in 1885 when Japanese PM Itō Hirobumi met with Li Hongzhang in Tientsin to discuss relations. • In the Convention of Tientsin, both sides promised to withdraw their troops and inform each other first before sending troops in future. • Despite this, China was determined to reassert its influence, appointing Yuan Shikai as ‘Imperial Resident of Seoul’. He effectively dictated Korean government policy for the next ten years. Li Hongzhang Itō Hirobumi Yuan Shikai Causes of the Sino-Japanese War • Tensions came to a head in 1894. The Tonghak Rebels were advancing on Seoul when King Kojong called on China for aid. • Both Japan and China rushed troops to the region to protect their interests. Japan got their first, seizing the Royal Palace and installing a pro-Japanese government. • China rejected this new government and in-turn, Japan claimed China had not informed it of sending troops. War loomed. Events of the War • It finally broke out on 25th July 1894 when Japanese ships sunk a Chinese troop transport. • By September, the main Chinese force at Pyongyang had been defeated along with the Chinese Beiyang Fleet at the Battle of the Yalu River. • In October Japanese forces crossed into Manchuria, taking Lushan (Port Arthur) in November where they massacred civilians. Sinking of the Kowshing Events of the War • In January 1895, 20,000 Japanese troops marched across the Shandong Peninsula, capturing the defensive forts surrounding Weihaiwei and turned the gun on the remnants of the Chinese Beiyang Fleet, completely destroying it. • By March, Japanese forces had captured the Pescadore Islands on the way to Taiwan. By April, China was defeated and sued for peace. Capture of Weihaiwei 1895 The Treaty of Shimonoseki • Li Hongzhang and Prince Gong were sent to negotiate the peace. They signed the Treaty of Shimonoseki on 17th April 1895. It stipulated: • China had to recognise Korean independence • Ceded the Liaodong Peninsula • Ceded Taiwan & Penghu Island • Gave 200 million Kuping Taels • Japanese allowed to operate on the Yangtze River and other trade concessions Prince Gong Li Hongzhang Effects of the War on the Reform Movement • The war had a profoundly significant effect on China. It had shown that despite reforms, China was no match for the recently modernised Japan. • The humiliating Treaty of Shimonoseki angered many Confucian scholars and officials into demanding further and immediate reforms. In this sense, the spirit of Self-Strengthening lived on. Effects of the War on the Reform Movement • Conservative Scholars like Zhang Zhidong & Weng Tonghe were reawakened to the need for reform and a consensus emerged that reform was necessary. • Zhang developed the idea of ‘TiYong’ which gave many people hope and reassured conservatives – ‘Chinese learning should remain the essence, but Western Learning should be used for practical development.’ Zhang Zhidong Weng Tonghe Causes of the 100 Days Reforms • This clamour for reform boiled over in Spring 1895 when 600 Confucian Scholars, gathered in Beijing for the Jinshi examinations, wrote a long memorial to the emperor – urging continued resistance against the Japanese through modernisation. Kang Youwei Liang Qichao • They were led by the scholars Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao. Kang & Liang were of a new school of reformers, who advocated drastic institutional change. Kang was also friends with the Emperor’s tutor, Weng Tonghe, who saw that the young Emperor would read it. Weng Tonghe Imperial Court Politics • The Imperial Court was dominated by conservative Confucian officials. They all realised that reform was necessary but competed to lead these reforms in order to retain power. • These officials were divided into two main groups: the ‘Northern Party’ led by Hsü T’ung and the ‘Southern Party’ led by Weng Tonghe. Zhang Zhidong • The Northern Party appointed Zhang Zhidong to lead the reform movement within Court. However this was blocked by Weng Tonghe who appointed promising young scholars like Kang Youwei. Kang turned out to be far more radical then expected! Weng Tonghe Causes of the 100 Days Reforms • Emperor Guanxgu was interested in the proposals but had no real power as the Court was still dominated by Cixi and her conservative friends. • But by the 1890s, calls for reform by were becoming widespread and the young emperor was looking to regain power to implement reforms. • In June 1898, the Emperor even had a private audience of over 5 hours with Kang Youwei. Listening to his ideas he become determined to institute a reform programme and made Kang his advisor. Empress Dowager Cixi Emperor Guangxu Kang Youwei Kang: “The four barbarians are all invading us and their attempted partition is gradually being carried out: China will soon perish.” Emperor: “Today it is really imperative that we reform.” Kang: “It is not because in recent years we have not talked about reform, but because it was only a slight reform, not a complete one; we change the first thing and do not change the second, and then we have everything so confused as to incur failure, and eventually there will be no success.” “The prerequisites of reform are that all the laws and the political and social systems be changed and decided anew, before it can be called a reform. Now those who talk about reform only change some specific affairs, and do not reform the institutions.” Emperor: “Your reform program is very detailed.” Kang: “…why not vigorously carry it through?” Emperor: “What can I do with so much hindrance?” Kang: “According to the authority which Your Majesty is now exercising to carry out the reforms, if he works on only the mist important things, it will be sufficient to save China…” Highlights of the five-hour interview by Liang Qichao, in I.C.Y Hsu, Rise of Modern China, p369-370 The 100 Days Reforms • Suddenly in June 1898, the Emperor began issuing an extraordinary series of edicts and decrees in quick succession. • Over 200 edicts were issued between June and September (103 days) and called for changes in four main areas of Qing government and life: Education, Government, the Military and the Economy. Emperor Guangxu Education Reforms A. Replacement of the eight-legged essay in the civil service examination by essays on current affairs B. Establishment of an Imperial University at Peking C. Establishment of modern schools in the provinces devoted to the pursuit of both Chinese and Western studies… D. Establishment of a school for the overseas subjects E. Creation of a medical school under the Imperial University F. Publication of an official newspaper G. Opening of a special examination in political economy Government Administration Reforms A. Abolition of sinecure and unnecessary offices B. Appointment of the progressives in government C. Improvement in administrative efficiency by eliminating delays and by developing a new, simplified administrative procedure D. Encouragement of suggestions from private citizens, to be forwarded by government offices on the day they are received E. Permission for the Manchus to engage in trade Economic Reforms A. Promotion of railway construction B. Promotion of agricultural, industrial, and commercial developments C. Encouragement of invention D. Beautification of the Capital Other Reforms A. Tour of foreign countries by high officials B. Protection of missionaries C. Improvement and simplification of legal codes D. Preparation of a budget How did the Reforms end? • Unfortunately, most of the reforms were boycotted by senior officials in the court and in the provinces. Some officials were willing but had not the ability to carry out reforms. • At first, Cixi and officials supported reforms but soon disliked the radical changes as they challenged their positions. The reforms to education would have destroyed the power of Confucian officials. Empress Dowager Cixi • Many officials begged Cixi to stop the reforms. Cixi believed the reforms were an attempt to wrestle power from her. How did the Reforms end? • The reformers feared Cixi would try to depose the Emperor. They planned to carry out a palace coup against Cixi and asked Yuan Shikai to support them. • Yuan Shikai betrayed the Emperor and informed Cixi of the plot. She immediately raided the Emperor’s palace and imprisoned the Emperor on 21st September 1898. • She announced publicly that a ‘serious illness’ had overcome the emperor, and she need to rule for him. Yuan Shikai How did the Reforms end? • Orders were quickly issued to arrest Kang. He and Liang fled to Japan, with other reformers being executed. Provincial officials that did support the reforms were stripped of their titles. The ‘six gentlemen’ • Most of the reforms were reversed: newspapers closed, formation of reform societies prohibited and the eight-legged essay reinstated. • However some reforms continued. Peking University and provincial schools remained. Cixi made it clear that reform was not bad but Kang Youwei had carried it out badly. Kang Youwei Reasons for the Failure of the Reform • The historian Hsü (2000) argues that there were three main reasons for the failure of the reform: 1. Inexperience of the Reformers 2. Powerful Conservative Opposition 3. The Power of Cixi 1. Inexperience of the Reformers • Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao had no previous experience in government service and had limited understanding of Western culture and institutions. They were naïve to think the support of the Emperor was enough and ignored the obvious fact that Cixi had real power. • Reforms were too radical and ambitious: education reforms angered students, elimination of traditional gov. offices angered officials, military reforms angered Manchu Officers etc… Kang Youwei Liang Qichao 2. Powerful Conservative Opposition • The reforms were seen by conservative scholars as a war on the whole Confucian state and society and saw Kang’s interpretations of Confucius as blasphemous. • Moderate conservative reformers like Weng Tonghe were alienated by the speed and extent of change. • Manchu officials were worried about their positions as all the reformers were Han Chinese. “Kang’s face is Confucian… but his heart is barbarian… The Modern Text school of today is not the same as that of the Han period; the latter honoured China whereas the former, the barbarians… even if Kang’s words might be accepted, he as a person should never be used… [he has the respect for] …neither the sovereign nor the fathers.” Yeh Te-hui & Wang Hsien-ch’ien 3. The Power of Cixi • Though in retirement since 1889, Cixi commanded huge influence over political and military affairs. • Confidants in the Grand Council reported to her all policy decisions and eunuchs in the palaces spied on the Emperor. • She also had the loyalty of the military surrounding Peking. Kang and the reformers had no power base other then the Emperor himself. Yuan Shikai held the key but he chose Cixi over the Emperor. Effects of the 100 Days Reforms 1. Revolutionary Growth - Progressive reform from the top down now seemed impossible. Only overthrow of the Qing Dynasty and revolution could change this. Led to the growth of Sun Yat-sen’s revolutionary movement. Sun Yat-sen 2. Growth in Anti-foreign Feeling at Court – The re-establishment of conservative influence at Court led to growth of antiforeign feeling as Western Powers opposed Cixi’s coup and helped Kang to escape. Cixi would later support the antiforeign Boxer Uprising in 1900-1901. Effects of the 100 Days Reforms 3. Growth in Chinese Nationalism- Diehard conservative Manchu officials were re-appointed, leading an antiChinese policy to punish reformers. This led to growing anti-Manchu and Qing feeling, indirectly leading to 1911 Revolution. “Reform benefits the Chinese but hurts the Manchus. If I have properties, I would rather give them to my friends than let the slaves share the benefit.” 4. Continued Reforms – Despite ending the 100 Days Reforms, she realised that reform was necessary, paving the way for the late Qing reforms in 1901- Grand Secretary Kang-i 1911. Plenary 1. What effect did the Sino-Japanese War have on the SelfStrengthening Movement? 2. Which officials spearheaded the reform movement after the war? 3. How was Kang Youwei different from the conservative reformers? 4. What types of reforms were announced by Guangxu? 5. Why did the Reforms fail? 6. What were the effects of the 100 Days Reform on China? Did we meet our learning objective? L/O – To analyse the significance of the Sino-Japanese War and identify the causes & effects of the 100 Days Reform Paper 3 - Exam Question 1 (2013) • Discuss the reasons for, and the consequences of, the Hundred Days Reform (1898) in China. (20 marks) Guangxu (Kuang-hsu) became emperor in his own right in 1889, though initially he was still heavily influenced by the Empress Dowager, Cixi (Tz’u-hsi). The humiliating defeats of the 1884–1885 Sino–French War and the 1894–1895 Sino–Japanese War and the subsequent scramble for concessions by the European powers indicated that the limited modernization of the Self-Strengthening Movement had failed. Various scholars and intellectuals advocated more progressive reform. The radical reformers, who believed in constitutional monarchy and institutional reform from the top, similar to the Meiji reforms in Japan, gained support from the Emperor. The main proponents of these changes were Kang Youwei (K’ang Yu-wei) and Liang Qichao (Liang Ch’i-ch’ao). By 1898 the Empress Dowager had removed herself from active participation in government and the Emperor was thus able to introduce the reforms by decree over a period of 103 days. The reforms covered the modernization of education, including the abolition of the traditional examination; political administration; industry; improvement and simplification of the legal codes; the preparation of a budget; and other matters. The conservatives opposed the changes in administration, education and the examination system, which would have weakened their influence. The Empress Dowager became alarmed at the extent of the reform programme and brought it to an end. Candidates may use Hsu’s analysis for the reasons why the Hundred Days Reform Movement failed: the reformers’ inexperience and naivety; the power of Cixi (Tz’u-hsi); the strength of the conservative opposition. The immediate consequences were the placing of Guangxu (Kuang-hsu) under house arrest and Cixi (Tz’u-hsi) taking over the regency again; the reversal of most of the reform measures; the execution of key reformers and persecution of others. The long term consequences included: progressive reform from the top was no longer a viable option for China; the return of Cixi (Tz’u-hsi) and the conservatives to power and hence a rigidity in approach to government; anti-foreign sentiments grew and influenced the 1900–01 Boxer Rebellion; the punishment of the reformers widened the division between Manchu and Han; repercussions with regard to the loyalties of some Han provincial leaders; disillusionment amongst the middle class in the treaty ports; many Chinese intellectuals fled into exile; reformist and revolutionary groups flourished in exile; a growth in the belief that the violent overthrow of the Qing (Ch’ing) dynasty was the only option; support for the ideas of Sun Yixian (Sun Yat-sen) and his Revive China Society and later the 1905 Tongmenghui (T’ung-meng hui) or Revolutionary Alliance. Paper 3 - Exam Question 2 (2005) • Why, and with what consequences for China, did the 100 Days Reform of 1898 fail? (20 marks) The question focuses on the reforms initiated by Kang Yuwei (K’ang Yu-wei) and Emperor Guangxi (Kuang-hsu) between 11 June and 20 September 1898, when some forty to fifty decrees were issued to reform education, government administration and the legal system, to promote railways, industry and commerce and to improve agriculture. The main reasons for failure were the inexperience of the reformers, their misguided strategy for introducing reform, the opposition of powerful conservative groups, and the reluctance of the Empress Dowager to surrender power. The effects of failure were far-reaching. It made clear that the court was in need of new leadership and that reform could not be imposed from the top against the opposition of the Empress Dowager and the conservative elite. The inability of the Emperor to order the regional authorities was demonstrated. Anti-foreigner sentiment increased, leading to the Boxer Rebellion and its consequences. Reformers wishing to retain the Manchus were discredited and the movement to overthrow the Manchus and to impose more radical reform grew in strength. Both parts of the question need to be addressed. Paper 3 - Exam Question 3 (2006) • “The Hundred Days Reforms (1898) had no chance of success.” How far do you agree with this statement? (20 marks) The reforms were introduced by the Emperor Guangxu (Kuang H’su), advised by the reformer Kang Youwei (K’ang Yu-wei), after the humiliation of defeat in the Sino-Japanese War (1894–5) and the consequent Scramble for Concessions. The Empress Dowager had removed herself from active participation in government and the Emperor was thus able to introduce the reforms by decree. The reforms covered education, political administration, industry, the preparation of a budget and other matters. However, conservatives opposed the changes in administration, education and the exam system, which would have weakened their influence. The Empress Dowager became alarmed at the extent of the reform programme and brought it to an end.