C-Lester-Diversification-of-the-Mississippi

advertisement

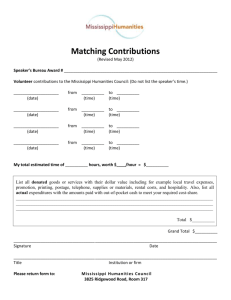

DIVERSIFICATION OF MISSISSIPPI’S ECONOMY MAKING THE TRANSFORMATION TO THE GLOBAL ECONOMY GOALS • To understand the economic repercussions of World War II on Mississippi • To understand the economic consequences of segregation and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 • To understand the effect of globalization on the Mississippi economy • To understand Mississippi’s economy in the 21st Century MISSISSIPPI’S ECONOMY AFTER WWII International Harvester onerow cotton picker Impact of WW II World War II was “a convenient and readily identifiable era, before which there was basic historical continuity for a century, but after which nothing ever again was quite the same.” John Ray Salter STATE AND NATIONAL CHANGES THAT AFFECTED THE POST-WAR ECONOMY • As a result of the war, the Delta lost 19% of its inhabitants who served in the military or worked in defense industries and never returned. • Delta planters who had been incentivized to experiment with technology through AAA payments during the New Deal now embraced highly capitalized machine agriculture and sharecropping disappeared. • The Gulf Coast benefitted from military investment in bases and defense industry (Ingalls Shipyards in particular). In post-war America the South would emerge as a strong advocate of continued military spending. • Returning veterans claimed their GI Benefits to purchase homes, start businesses, buy machinery for farms, and attend college CIVIL RIGHTS AND THE MISSISSIPPI ECONOMY Image from inside a Freedom Ride bus as it entered Jackson THE ECONOMIC COSTS OF SEGREGATION • According to the U.S. Census, Mississippi’s population was 58.5% African American in 1900, 45.3% in 1950, and 36.3% in 2000. • Segregation was inefficient in that it imposed high economic costs by limiting investment and access to human capital. • Educational opportunities were limited for black children • Low wages and sharecropping limited the consumer spending of blacks and poor whites • Focus on agriculture inhibited urban growth which inhibited innovation, the engine of economic growth. ECONOMIC EFFECTS OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1964 • Title VII of the Civil Rights Act opened a wide range of job opportunities for African Americans without negatively impacting white opportunities. • National employers and employers with government contracts led the way in integrating the workplace. President Lyndon Johnson’s 1965 Executive Order 11246 prohibited discrimination in firms with federal contracts. • South’s (and Mississippi’s) largest industry was textiles, and its desegregation was the largest contributor to increases in black incomes between 1965 and 1975. • Rise in black education levels as reflected in high school and college graduation rates. Jobs now available to blacks that called for more education and specialized skills. “THE MOST SOUTHERN PLACE” IN A GLOBAL ECONOMY EFFECT OF AUTO MANUFACTURING, GAMING, AND OIL ON MISSISSIPPI ECONOMY • According to a 2013 Mississippi State University Study, the ten years of production at the Nissan plant in Canton have almost doubled median income, reduced poverty in Madison County to an all-time low of 13%, increased the number of housing unites in Madison County by 27,000, and employed 16,000 workers. • Mississippi had 29 state-licensed casinos in 2014 that produced $2.08 billion in revenues, $247.8 million in tax revenues, employed 22, 277 casino employees, who earned $710.7 million in wages. • A 2011 oil and gas industry report places the number of workers employed at 97,800 or 6.6% of the state’s total employment with a combined income of $4.22 billion. INEQUALITY IN MISSISSIPPI • In 2014, Mississippi had the highest level of child poverty in the nation. Being born into poverty in Mississippi is more likely to result in a lifetime of poverty than in other U.S. state. • Nine counties in Mississippi have a per capita income below $13,000/year (2014). • Five counties in 2014 had unemployment rates above 17%. • Forbes magazine found investors who rated Mississippi last on their lists of potential projects did so because they viewed the state’s educational opportunities and health care as detrimental to worker productivity. NEW ECONOMY OR OLD ECONOMY IN NEW CLOTHES? • The South is home to the fastest growing population in the U.S. The second and third largest states are ex-Confederate states. Mississippi has not yet doubled its population in the 115 years since the 1900 census. • Urbanization has become a hallmark of the southern economy with Miami, Atlanta, Charlotte, Dallas, Houston, and Fort Worth as leading examples. Mississippi remains largely a rural state, with Jackson its largest city, a size that according to a Mississippi State report would make it the fifth largest city in Alabama. • The new southern population is diverse, not simply black and white. In the 2010 census, Mississippi’s Hispanic population was 3.2% and its foreignborn population was 2.2%. • Two of the largest high tech corridors are in the South—in Texas and North Carolina. Two others, the Florida High Tech Corridor and the I-85 Corridor are up and coming tech incubators. Although Mississippi universities boast high tech centers, no synergy for high tech incubators has developed. • Mississippi still experiences a “brain drain” of engineers, computer scientists, mathematicians, and scientists who will build the next generation of innovations that will drive the future economy. CONCLUSION • Mississippi has participated in an economic transformation that shifted the state’s economy from agriculture to industry and from a dependency on low wage industries to high wage manufacturing, tourism/gaming, and resource extraction. • Despite the gains, Mississippi’s economy continues to suffer from high levels of inequality and low levels of innovation.