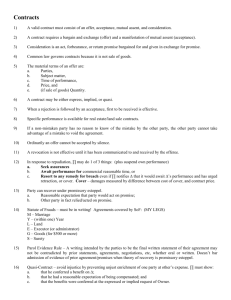

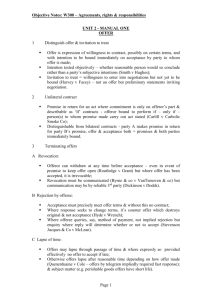

Document

advertisement