1.0ChptSpain

advertisement

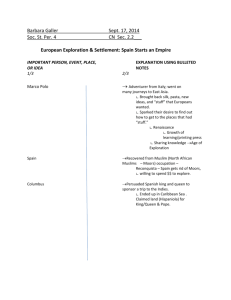

Chapter One España This book “The de Riberas” is a celebration of the sacrifices made by my progenitors, a way to pay homage to the part they played in the founding of the northern areas New Spain. It is also an appreciation of their contributions to this great nation, the United States of America. To be sure, this is not a historical book. I leave that to the real historians. Much of this information is gleaned from the internet and used to explain one family’s descendents in various historical timelines using the history at each stage as a backdrop. Please forgive my writing style, as I’m not a professional writer. This family history is a labor of love and not meant to be anything else. I felt it necessary to discuss Spain and its people before proceeding with the story of the de Riberas. The family was after all a product of their Spanish history and culture. Their view of the world of their time was what shaped them and the New World which they came to settle. I have only just come to understand how little I know about my forbearers. Even the length of four hundred years of New World history tells little about a family or a man’s background. The de Riberas were Spaniards. They left the Old World’s beautiful Iberian Peninsula for the New World, specifically New Spain’s most northern frontier. The families settled in Santa Fe, New Mexico about 1695. The other lines had progenitors that arrived in Santa Fe earlier, in 1599. This began their life in a brave new world. What follows is but the shadow of a rich and complex tapestry of the times and places, and those men and women who once lived them. As I knew little of Spain this work has taken me on quite a journey of discovery about that wonderful nation known as Spain. I spent some time there when a young man and participated in the running of the bulls in Pamplona. Today’s Spain is located on the Iberian Peninsula in southwestern Europe and is officially called the Kingdom of Spain or Reino de España. Spain’s mainland is bordered to the south and east by the Mediterranean Sea except for a small land boundary with Gibraltar. On the north and northeast it’s bordered by France, Andorra, and the Bay of Biscay. In the west and northwest Portugal and the Atlantic Ocean are its borders. Spain, France, and Morocco are the only three countries to have both Atlantic and Mediterranean coastlines. Spain's border with Portugal is the longest uninterrupted border within the European Union. Spanish territory also includes the Balearic Islands in the Mediterranean, the Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean off the African coast, three exclaves in North Africa, Ceuta, Melilla, and Peñón de Vélez de la Gomera that border Morocco, and the islands and Peñónes (rocks) of Alborán, Chafarinas, Alhucemas, and Perejil. With an area of 505,992 km2 (195,365 sq mi), Spain is the second largest country in Western Europe and the European Union, and the fifth largest country in Europe. Modern humans first arrived on the Iberian Peninsula around 35,000 years ago. Many, many things have happened on the Peninsula since then. However, for most little is known or understood about Spain’s past. It would be safe to say that the majority of those queried know nothing on the subject of Spain, its people, its history or its importance to world history. Very, very few are aware that the Peninsula came under Roman rule around 200 BCE, after which the region was named Hispania. More might understand that in the middle Ages the area was conquered by Germanic tribes. A greater number possibly would know that to Iberia’s south it was conquered later by the Moors about 710 AD. Few could understand the impact of the Moors on the Spanish psyche. Some people have a vague idea about Spain’s emergence as a unified country in the 15th Century, following the marriage of the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella and the completion of the centuries-long reconquest, or Reconquista, of the Peninsula from the Moors in 1492. If pressed, a few would have a sprinkling of knowledge that in the early modern period, Spain became one of history's first global colonial empire, leaving a vast cultural and linguistic legacy that includes over 500 million Spanish speakers, making Spanish the world's second most spoken first language. If questioned, some would say that Spaniards look Mediterranean and one cannot be sure if they are Italian or Portuguese. They might also add that most have dark hair and dark eyes but there are those with light hair and light eyes. The person answering might also say that their look is not as diverse as the people in the United States or the United Kingdom. There a person could look like Jackie Chan or Ian Wright and if asked, say “I'm British, but really from X.” The most accepted answer is that Spaniards are white Mediterranean’s, darker than their Northern Europeans EU counterparts would have lighter complexions. Therefore, if a southern Italian or Spaniard has olive skin, it´s normal for them to be confused with another nationality from another part of the world. What the poorly traveled fail to notice is that nationalities such as Italians, Spaniards, Portuguese, etc. physical appearance differs a great deal within their countries. In northern Italy you will find a region called "Alto Adige" and area which belonged to Austria in the past. The population is from Germanic origins and has nothing to do with someone from Calabria (Southern region). Ignorance is understandable. People tend to know less about Spain than the UK, France, Italy, Germany, and Russia. This may be due to Spain’s diminished world role since the Spanish American War and its playing a sideline role in WWII. Thus, its limited involvement in the 20th Century narrative taught in history courses. High school classes in America teach the history of exploration and the colonization of America. In that context there is a mention of Spain. Teachers speak of Spanish conquistadors, the Armada, etc. There is little emphasis on Spanish culture, Spanish life, history or geography. So let us begin again with some facts. But what is Spain? Modern Spain is a democracy organized in the form of a parliamentary government under a constitutional monarchy. It is a developed country with the thirteenth largest economy in the world. It is a member of the United Nations, NATO, OECD, and WTO. Spanish or Español, also called Castilian or Castellano is a Romance language that originated in the Castile region of Spain. Approximately 470 million people speak Spanish as a native language, making it second only to Mandarin in terms of its number of native speakers worldwide. There are an estimated 548 million Spanish speakers as a first or second language, including speakers with limited competence and 20 million students of Spanish as a foreign language. Spanish is one of the six official languages of the United Nations, and it is used as an official language by the European Union, Mercosur, and the Pacific Alliance. Spanish is spoken fluently by 15% of all Europeans, making it the 5th-most spoken language in Europe. Spanish is a part of the Ibero-Romance group of languages, which evolved from several dialects of common Latin in Iberia after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th Century. It was first documented in central-northern Iberia in the 9th Century and gradually spread with the expansion of the Kingdom of Castile into central and southern Iberia. From its beginnings, Spanish vocabulary was influenced by its contact with Basque, as well as by other IberoRomance languages, and later it absorbed many Arabic words during the Muslim presence in the Iberian Peninsula. It also adopted many words from non-Iberian languages, particularly the Romance languages Occitan, French, Italian and Sardinian and increasingly from English in modern times, as well as adding its own new words. Spanish was taken to the colonies of the Spanish Empire in the 16th Century, most notably to the Americas as well as territories in Africa, Oceania and the Philippines. Spanish is the most popular second language learned by native speakers of American English. From the last decades of the 20th Century, the study of Spanish as a foreign language has grown significantly, in part because of the growing populations and economies of many Spanish-speaking countries, and the growing international tourism in these countries. Spanish is the most widely understood language in the Western Hemisphere, with significant populations of native Spanish speakers ranging from the tip of Patagonia to as far north as Canada and since the early 21st Century, it has arguably superseded French as the secondmost-studied language and the second language in international communication, after English. There are a great many language differences between Spain and Mexico. Some variations are regional are by country (The Spanish of Spain Vs Argentina or Cuba). The comparison may not be completely accurate. The difference between the Spanish of Spain and the Spanish of Latin America is much like the language differences between British English and American English. With few exceptions some local accents can be difficult for outsiders. There are differences more so in the spoken language than in writing. The history of Spain begins for most Americans with some knowledge of the Muslim conquest of Iberia in 711. Muslim armies from North Africa crossed the Straits of Gibraltar and entered the southern region of Spain. During the next seven years, the Muslims conquered the weak kingdom of the Visigoths and firmly established themselves on the lower areas of the Iberian Peninsula. They called their territory al-Andalus or "Vandal land". Fortunately for the future Spaniards, the Moors had left this northern part of Spain unconquered, marking what became the first battle in what the Spanish called the “Reconquista,” or Reconquest of Spain for Christendom. Christian resistance to Muslim advances began almost immediately. However, the notion of a Christian holy war designed to exterminate or at least to expel the Muslims, and not simply to reconquer Spanish Christian territories, did not set in until the 11th Century during the reign of Alfonso VI (1085-1109). In this era of crusading reconquest, a need arose for the living presence of religious-national figures, capable of rallying around themselves the Spanish Christian forces. Two figures emerged as emblems of Christian strength and supremacy: El Cid and Santiago. They fulfilled the needs of the Iberian Christians for heroes to emulate, and united them in their struggle for political and religious independence from Muslim rule. As Christian paragons, Santiago and El Cid became increasingly identified with one another. Christians attributed identical symbols to them, and their images merged to the point of being indistinguishable in the artistic depictions of these historical individuals in the eleventh through thirteenth centuries. The unification of the spiritual and the secular, symbolized by the convergence of these figures’ images, marked the birth of the formation of a united Spanish Christian kingdom, and the creation of a unique national-religious identity in Spain. Under the leadership of Alfonso VI a decisive program of crusading reconquest began. The monarch’s objective entailed uniting all of Spain under one crown and one religion. Tolerance and coexistence with the Muslims were no longer options if Alfonso sought to create a truly unified Spanish Christian kingdom. Thus, Santiago and El Cid grew to immense national and religious proportions because both fulfilled an historical need. Santiago represented the spiritual component of Alfonso’s agenda. The Leonese monarch called upon Spaniards to fight against the Muslims and establish the supremacy of the Catholic Church. To ensure the success of the reconquest, Spaniards believed God sent his vassal Santiago to lead them in battle and help them realize their goal. El Cid represented the secular element of the Christian Reconquista. As Alfonso’s vassal, El Cid united the Spaniards in their struggle to oust the infidels and reclaim the peninsula for the Spanish Christian monarch Alfonso and his peoples. The Christian reconquest created faith in Santiago and El Cid as leaders who inspired resistance to the Muslims, and promised ultimate victory over Islam. Despite the similarities these figures acquired in their roles as Spanish crusaders, their origins could not be more diverse. Santiago or St. James was the son of Zebedee, a fisherman in Galilee, and Salome, the sister of the Virgin Mary. He and his brother John the Evangelist were devout disciples of Christ, and such zealous preachers of the good news that Christ named them Boanerges, "the brothers of thunder." In 44 A.D. Santiago became the first of the Twelve Apostles to suffer martyrdom when Herod Agrippa I arrested and beheaded him in Jerusalem. Tradition places Santiago in Spain proselytizing prior to his execution. Why then would his body be buried in Spain if he died in Jerusalem? According to legend, Santiago’s disciples Athanasius and Theodore took his body back to Spain when a ship miraculously appeared, guided by an angel, to transport them. They buried the saint in the area known today as Compostela, "field of stars," where Santiago lay forgotten for nearly eight centuries. The rediscovery of the saint’s long-forgotten tomb in the 9th Century occurred, tellingly enough, in a time of need "when Christian political fortunes in Spain were at their lowest ebb." Christians suffered defeat time and again at the hands of the Muslims, until God unearthed the saint’s remains, and inspired them with the confidence that God was on their side, fighting in the battlefield with them through the figure of Santiago. "God gave us aid and we won the battle." Christians endorsed the veracity of this claim by referring to the battle of Clavijo in 844. The night before the battle, Santiago appeared in a dream to the leader of the Spanish forces, King Ramirez of Castile, and promised him a victory over the Muslims in the fields of Clavijo. The following day, as Christians fought the Muslims, the warrior-saint appeared on the battlefield in full armor riding on a white charger, with a sword in one hand and a banner in the other. Together with Santiago Matamoros, the Moorslayer, the Christians slaughtered the Muslim invaders and won a decisive victory. Undoubtedly, Santiago appeared in the battlefield at Clavijo for he left behind impressions of scallop shells (his symbol as the pilgrim saint) on the rocks in the field and even on the stones of neighboring houses. After this battle, Santiago’s name became the Christians’ battle cry, and his appearance in warfare the symbol of Christian victory. According to legend, the saint aided the Spaniards at least forty times in earthly warfare, including the battle of Clavijo. This was a "brave assertion of faith in St. James, in the miracle at Clavijo, and in the patron saint’s heavenly care for Spain." The Spaniards "needed Santiago as the supernatural ally who would sustain their courage and bring certain success to their arms." This strong faith identified Santiago with the religious element of the reconquest and the revival of Spanish fortunes. It follows then, that at the end of the 11th Century when a decisively religious element entered the equation of the Reconquista, an aggressive program of dignifying the apostolate of James and of exalting Compostela as the "second Rome" took place. The image of Compostela as a "second Rome" points to the site’s religious significance, and established its importance as a preeminent place of pilgrimage. Over the next centuries several Christian kingdoms emerged in Spain, notably: Asturias León Castile Kingdom of Asturias The Kingdom of Asturias was, in origin, a Visigoth kingdom of Spain created by Pelayo (Pelagius), a grandson of King Chindaswinth, who had been defeated by the Moors. Pelayo established his capital at Cangas de Onis, securing his independence with a victory at the Battle of Covadonga. The Moors, rather than sending more soldiers into Asturias, headed into France and in 732 were defeated at the Battle of Tours. For the next century the Moors were on the defensive and this allowed Pelayo and his successors to rebuild their strength. Pelayo’s son, Favila, became king on his father’s death in 737 but died two years later in a boar hunt. He had no son so his brother-in-law was proclaimed King Alfonso I. He enlarged the kingdom of Asturias by annexing Galicia in the west and León in the south. This area is coincidently the birthplace of the de Ribera family. He also extended his lands in the east to the borders of Navarre. When Alfonso died, his cruel son Fruela I came to the throne. One of Fruela’s first acts was to kill his own brother, Bimarano, who he thought wanted the throne. After reigning for 11 years, Fruela was murdered on January 14, 768, and was succeeded by his cousin Aurelius (son of Alfonso’s brother Fruela). He was, in turn, succeeded by Silo, a nephew, who had married Alfonso I’s daughter. Aurelius had managed to prevent the Moors from attacking by paying them tribute, and all that is known about Silo is that he moved the kingdom’s capital from Cangas de Onis to Pravia. This period coincided with Charlemagne’s invasion of Spain, and his capture of Barcelona. Silo’s successor, Mauregato, was an illegitimate son of Alfonso I (his mother allegedly being a slave) (r. 783-788) and was alleged to have offered 100 beautiful maidens annually as tribute to the Moors. The next king, Bermudo I, a brother of Aurelius, had been ordained deacon and reluctantly accepted the position as king, abdicating three years later and allowing Alfonso II “The Chaste,” a son of Fruela I, to become king. Initially people were worried that Alfonso might try to avenge the murder of his father—instead he ruled for 51 years. He had been married to Berta, said to have been a daughter of Pepin, king of the Frankish tribe, but they had no children as he had taken a vow of celibacy. During his long reign he stabilized the country’s political system and attacked the Moors, defeating them near the town of Oviedo, which they had recently sacked. Alfonso II was so impressed by the beauty of Oviedo that he moved his court there and proclaimed it his capital. It was to remain capital of the kingdom of Asturias until 910, when León became the new capital. Work began on the construction of the Oviedo Cathedral, where Alfonso II was eventually buried. Alfonso’s main achievement was that he conquered territory from the Moors, moving the reach of his Christian kingdom into the edges of central Spain. The Moorish king Abd arRahman II (r. 822-852) was, however, able to check the advances of Alfonso, drive back the Franks, and stop a rebellion by Christians and Jews in Toledo. The next king of Asturias was Ramiro I, a son of Bermudo I. He began his reign by capturing several other claimants to the throne, blinding them, and then confining them to monasteries. As a warrior he managed to defeat a Norman invasion after the Normans had landed at Corunna, and also fought several battles against the Moors. His son, Ordoño I, became the next king and was the first to be known as king of Asturias and of León. Ordoño extended the kingdom to Salamanca and was succeeded by his son Alfonso III “The Great.” Alfonso III reigned for 44 years (866-910) and during that time consolidated the kingdom by overhauling the bureaucracy and, then fought the Moors. He managed to enlarge his lands to cover the whole of Asturias, Biscay, Galicia, and the northern part of modern-day Portugal. The southern boundary of his kingdom was along the Duero (Douro) River. Kingdom of León Alfonso had three feuding sons who plotted against each other and then against their father. To try to placate them all, Alfonso divided his kingdom into three parts. Garcia became king of León, Ordoño became king of Galicia, and Fruela became king of Oviedo (ruling Asturias). This division was short-lived as wars among the young men resulted in all the lands eventually coming together under one ruler. García only reigned for four years before he died, without any children. Ordoño II ruled in Galicia before dying 14 years later and eventually Fruela II “The Cruel,” Alfonso III’s fourth son, who had outlived the others, reunited the kingdom in 924. However he died of leprosy in the following year, with Ordoño II’s son’s becoming King Alfonso IV. He did not want to rule and abdicated in order to spend the rest of his life as a monk. This allowed Alfonso IV’s brother to become King Ramiro II. Soon after this, Alfonso tried to regain the throne, only to be taken by his brother, blinded, and left at the Monastery of St. Julian, where he died soon afterward. Ramiro II was succeeded by his elder son, Ordoño III, and then by a younger son, Sancho I “The Fat.” There were two years when Ordoño IV “The Wicked,” a son of Alfonso IV, was king, but then Sancho I’s only son became King Ramiro III. He was five when he became king and the Normans decided to attack again, destroying many coastal towns. Eventually he abdicated and allowed his cousin, Bermudo II, son of Ordoño III, to become king. It was during the reign of Bermudo II that the Moors attacked and managed to get as far as León. When Bermudo II died in 999, his son Alfonso V was only five, and Don Melindo González, count of Galicia, became regent. In his 20s Alfonso V led his armies into battle against the Moors, recaptured much of León, but was killed in battle with the Moors at Viseu in Portugal, on May 5, 1028. His only son, Bermudo III, was 13 and during his nine year reign faced more threats from the neighboring Christian kingdom of Castile. In 1037 he was killed at the Battle of the River Carrion fighting King Ferdinand I of Castile, and the kingdom of León, as it was then known, was absorbed into Castile. In the northern provinces of Castile there lived a large class of minor nobles, the hidalgos. The inhabitants of Guipúzcoa (by the westernmost French border) even claimed that they were all of noble birth. But the south, New Castile (southeast of Madrid), Extremadura (southwest of Madrid), and especially Andalusia—that is, those provinces most recently reconquered from the Muslims—were the domain of the great nobility. There the Enríquez, the Mendoza, and the Guzmán families and others owned vast estates, sometimes covering almost half a province. They had grown rich as a result of the boom in wool exports to Flanders during the 15th Century, when there were more than 2.5 million sheep in Castile, and it was they, with their hordes of vassals and retainers, who had attempted to dominate a constitutionally almost absolute, but politically weak, monarchy. It was in this kingdom that the Catholic Monarchs determined to restore the power of the crown. Once this was achieved, or so it seemed, the liberties of the smaller kingdoms would become relatively minor problems. Like their contemporary Henry VII of England, they had the advantage of their subjects’ yearning for strong and effective government after many years of civil war. Thus, they could count on the support of the cities in restoring law and order. During the civil wars the cities of northern Castile had formed leagues for self-defense against the aggressive magnates. A nationwide league, the hermandad (“brotherhood”), performed a wide range of police, financial, and other administrative functions. Isabella supported the hermandad but kept some control over it by the appointment of royal officials, the corregidores, to the town councils. At the same time, both municipal efficiency and civic pride were enhanced by the obligation imposed on all towns to build a town hall (ayuntamiento). With the great nobles it was necessary to move more cautiously. Castile, too, was a poor country. Much of its soil was arid, and its agriculture was undeveloped. The armed shepherds of the powerful sheep-owners’ guild, the Mesta, drove their flocks over hundreds of miles, from summer to winter pastures and back again, spoiling much cultivated land. Despite the violent hostility of the landowners, the government upheld the Mesta privileges, since the guild paid generously for them and was supported by the merchants who exported the raw wool to the cloth industry of Flanders. The activities of the Mesta were undoubtedly harmful to the peasant economy of large parts of Castile and, by impoverishing the peasants, limited the markets for urban industries and thus the growth of some Castilian towns. Kingdom of Castile and Granada The kingdom of Castile began as a dependency of León and was controlled by counts. However in 1035 Ferdinand I “The Great” was proclaimed king of Castile and two years later after defeating and killing Bermudo III became king of Castile and León, ruling for the next 27 years. These new kings saw themselves as lineal descendants of the heritage of Asturias, even if not by blood. When Ferdinand I died he divided his lands among his children and Sancho received Castile, Alfonso received León and Asturias, García was given Galicia and northern Portugal, his daughter Urraca was given Zamora, and Elvira was given Toro. This was meant to end squabbling by them but only ended up with much fighting. At this time, a nobleman, Rodrigo Díaz de Bibar, emerged as the great Spanish hero El Cid. Interestingly he later tried to set up his own kingdom of Valencia, which ended in his death. Eventually Alfonso ruled all the lands as Alfonso VI “The Brave,” king of Castile. Alfonso VI launched a number of attacks on the Moors but most of these were overshadowed by the efforts of El Cid. In 1085 the Christians were able to capture the city of Toledo, and Alfonso reigned until his death in June 1109 at the age of 70. He had five or six wives. His daughter Urraca succeeded Alfonso VI. She married first Raymond, count of Burgundy, and later Alfonso I, king of Aragon. Her successor was Alfonso VII (r. 1126-1157), titling himself as “Emperor of All Spain.” When he died his lands were divided between his eldest son, Sancho III “the Desired,” who was given Castile; and his second son, Ferdinand II, who was given León. Sancho III only reigned for a year and his only surviving son became Alfonso VIII, r. 1158-1214. In 1212 he defeated the Moors at the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, giving Castile control over central Spain. When he died, Henry I, his youngest but only surviving son, succeeded him. He died and was succeeded as king of Castile by his nephew Ferdinand III. Meanwhile in León, Ferdinand II had reigned for 31 years, and when he died in 1188, his brother, Alfonso IX, succeeded him. Alfonso IX’s first wife Teresa, from whom he was divorced, was later canonized as Saint Teresa in 1705. His eldest surviving son with his second wife was Ferdinand, who had already become king of Castile. When Alfonso IX died in 1230, the kingdoms of Castile and León were reunited. Ferdinand III embarked on a series of wars against the Moors, managing to capture the cities of Córdoba (1236), Jaen (1246), and Seville (1248). With the capture of Seville, the “Reconquista” was almost complete—the Moors held only the city of Granada. The forces of Ferdinand were unable to take that city, although the emir of Granada did acknowledge his overlordship. Ferdinand III also founded the University of Salamanca, died on May 30, 1252, and was buried in Seville Cathedral. In 1671 Pope Clement X canonized him, and he became St. Ferdinand (San Fernando). Ferdinand’s son, Alfonso X, had two titles, “The Wise,” and “The Astrologer.” During his reign he codified the laws, wrote poems, and had a large number of scholars produce a great chronicle of Spanish history. One of his advisers, Jehuda ben Moses Cohen, wrote that the king was someone “in whom God and placed intelligence, and understanding and knowledge above all princes of his time.” He was also elected as King of the Romans in 1257, renouncing the title of Holy Roman Emperor in 1275. However Alfonso X was faced with a dynastic succession crisis. His eldest son, Ferdinand de la Cerda, died in 1275, leaving two young sons; Alfonso X did not want a young boy on the throne so nominated as his successor his second son, Sancho. Ferdinand’s wife championed the cause of her two boys, and Alfonso X’s wife sided with her. The conflict continued when the French—Ferdinand’s wife was a French princess—declared war on Sancho, who had the support of the Spanish parliament, the Cortes. War seemed inevitable, but when news arrived that Sancho was ill, Alfonso died of grief and despair. Sancho IV “The Brave” became the next king, his illness being not as serious as was first thought, and after reigning for 11 years, he was succeeded by his son Ferdinand IV “The Summoned,” who was only nine when he became king—his mother ruled ably as regent. Little of note happened during Ferdinand IV’s reign and he gained his title from sentencing to death two brothers who had been accused of murdering a courtier. They went to their execution protesting their innocence and “summoned” Ferdinand to appear at God’s court of judgment in 30 days. As Ferdinand was only 26 years old at the time he was unconcerned, but on the 30th day after the execution his servants found him dead in bed. His one-year-old son, Alfonso XI “The Just,” became the next king and in 1337, when he was 13 years old, attacked the Moors of Granada. At the Battle of Río Salado on October 30, 1340, the Spanish, supported by the Portuguese, defeated a Moorish army. It was said to have been the first European battle where cannons were used. Alfonso XI reigned until 1350 when he was 39. Alfonso was married to Maria of Portugal but spent most of his reign with Leonor de Guzmán, a noble woman who had recently been widowed. Alfonso and Leonor had a large family but when Alfonso died, Leonor was arrested on orders of the queen and taken to Talavera, where she was strangled. The next king was the son of Alfonso and Maria, Pedro I “The Cruel,” who reigned from 1350 until 1366. During the reign of Pedro I he also married Blanche of Bourbon, cousin of the king of France, but fell in love with Maria de Padilla Daughter of Juan García de Padilla, 1st Lord of Villgera and María Fernández de Henestrosa. Initially Pedro appointed Maria’s friends and family to positions of influence, but some nobles forced the dismissal of supporters and relatives of Maria. In 1355, he had four of these noblemen stabbed to death, and apparently blood splattered over the dress of his wife, earning Pedro his title “The Cruel.” In 1366 he was deposed by his half brother Henry II of Trastamara, “The Bastard,” but managed to oust Henry and returned as king in the following year, spending the next two years in battles with his half brothers, and assisted by the English led by Edward the “Black Prince.” These events formed the backdrop of the French novel Agenor de Mauleon (1846) by Alexander Dumas. Eventually Pedro was murdered and Henry II was restored to the throne. Over the next 10 years, until Henry died, attempts were made, ultimately successful, to prevent John of Gaunt from invading Spain. Henry II’s only legitimate son was John I, 21 years old, and he became king when his father died. Some 11 years later, while watching a military exercise, John I fell from his horse and was killed. His 11-year-old son, Henry III “The Infirm,” became the next king. When he died in December 1406, his one-year-old son was proclaimed John II. When he was 13 years old, the Cortes declared the teenager to be “of age,” and John II ruled in his own right. The king had many favorites, one of whom was Don Alvaro de Luna, who later writers suggested was a boyfriend of the young king. John II reigned until his death in 1454, was succeeded by his son, Henry IV, who reigned until 1474. He had a daughter and before Henry IV died, the heiress, Isabella, married Ferdinand of Aragon, uniting Christian Spain. Kingdoms of Aragon and Navarre The Royal House of Aragon, in northeastern Spain, traces its origins back to Ramiro I (r. 10351063). His father, Sancho III, king of Navarre, had left him Aragon, as Ramiro was illegitimate. Ramiro was a warrior prince and quickly extended his lands, even briefly taking part in forays into the land of his half brother Garcia III, who had inherited the rest of Navarre. In a war with the Moorish emir of Saragossa over tribute, Ramiro was killed in battle on May 8, 1063. Ramiro’s successor was his eldest son, Sancho I, who managed to recapture lands from the Moors, pushing the boundaries of Aragon to the north bank of the river Ebro. In 1076, when his cousin, the king of Navarre, died, Sancho succeeded to the throne of Navarre. In June 1094, Sancho was killed during the siege of Huesca. His son and successor, Pedro I, then became king of Aragon and Navarre, carrying on the siege of Huesca for another two years. In 1096 he defeated a large Moorish army and its Castilian allies, at the Battle of Alcoraz, with help, legends state, from St. George. Pedro’s two children died young, and in grief both he and his wife died soon afterward. Pedro was succeeded by his brother Alfonso I “The Warrior.” Having no children he was succeeded by his younger brother, Ramiro II “The Monk.” Ramiro was only king for three years, abdicating to spend the remaining 10 years of his life in a monastery. His only child, Petronilla, became queen, when she was one year old. When she turned 15 in 1151, she married Ramon Berenguer IV, count of Barcelona. Twelve years later she abdicated the throne in favor of her son Alfonso II (r. 1163-96). His eldest son and successor was Pedro II, who was alleged to have kept scandalous company with many women. With the outbreak of the Albigensian Crusade in France, and the persecution of the Cathars in southern France, Pedro II led his army into the region to demonstrate the historical ties of Aragon to the region. He tried to stop the carnage that was taking place around Carcassone and urged the pope to recognize the area as a part of Aragon, not France, which would have ended the crusade. He failed and on September 13, 1213, at the Battle of Muset, was killed in battle with the crusaders led by Simon de Montfort. Pedro’s son James I “The Conqueror” was only five when he succeeded his father. After a terrible regency, James took control and led his armies in taking the Balearic Islands (1229-35), conquering Valencia from the Moors in 1233-45, and also in the campaign against Murcia in 1266. When James died his son, Pedro III, succeeded him, leading his armies against the Moors. He had a claim to the kingdom of Sicily through his wife and invaded the island in 1282, earning the title “The Great.” He was badly injured in the eye during fighting with the French and died soon afterward to be succeeded by his son Alfonso III “The Do-Gooder.” This interesting title came from the fact that he granted his subjects the right to bear arms. His brother and successor James II “The Just” conquered more land from the Moors and was in frequent disputes with the papacy. In 1310, he conquered Gibraltar, and possibly to placate Pope Clement V, two years later he suppressed the Order of the Knights Templar. James II was succeeded by his son Alfonso IV “The Debonair” or “The Good.” Most of his reign was spent in disputes over the islands of Corsica and Sardinia, which were captured by the Genoese. His son and successor, Pedro IV, held a huge coronation, apparently with as many as 10,000 guests, and earned the title “The Ceremonious.” He managed to lead his army into Sicily, which he recaptured, and when he died in 1387, his feeble son John I succeeded to the throne. His wife, Iolande de Bar, was actually in control of the kingdom. John died after being gored by a boar during a hunt, and his younger brother Martin “The Humane” became king. It was during his reign that the famous Santo cáliz was transferred to Valencia Cathedral, where it is still revered by many as the Holy Grail. It was said that St. Peter took it from the Holy Land to Rome, and it was taken to Valencia. Martin lost the throne of Sicily and when he died in 1410, there was a brief interregnum until Ferdinand I “The Just” was proclaimed king. Ferdinand I was the son of John I and was elected king by the nobles. When Ferdinand I died in 1416, after reigning for just four years, his eldest son, Alfonso V “The Magnanimous,” became king. There was a plot to overthrow him, and he refused to hear the names of the conspirators, allowing them to go unpunished. He spent much of his time and energy in his possessions in Italy: Naples and Sicily. When he died, his lands in Spain went to his brother John, who had been king of Navarre, and he became king of Aragon and Navarre. His Italian lands went to his illegitimate son Ferdinand. John II reigned from 1458 until 1479. His greatest achievement was arranging the marriage of his son, Ferdinand, to Isabella, heir to the throne of Castile. They were married in 1469 at Valladolid. When John died on January 19, 1479, the Christian kingdoms of Spain were united with Ferdinand and Isabella as joint rulers. In 1492, the armies of Ferdinand and Isabella finally took Granada, the last Moorish part of the Iberian Peninsula, ending the “Reconquista.” The Catholic Monarchs revoked usurpations of land and revenues by the nobility if these had occurred since 1464, but most of the great noble estates had been built up before that date and were effectively left intact. From a contemporary chronicler, Hernán Pérez del Pulgar, historians know how they proceeded piecemeal but systematically against the magnates, sometimes using a nobleman’s defiance of the law, sometimes a breach of the peace or of a pledge, to take over or destroy his castles and thus his independent military power. Even more effective in dealing with the nobility was the enormous increase in royal patronage. Isabella was stage manager to Ferdinand’s election as grand master of one after another of the three great orders of knighthood: Santiago, Calatrava, and Alcántara. This position allowed the king to distribute several hundred commanderships with their attached income from the huge estates of the orders. Equally important was royal control over all important ecclesiastical appointments, which the Catholic Monarchs insisted upon with ruthless disregard of all papal claims to the contrary. In the Spanish dependencies in Italy, Ferdinand claimed the right of exequatur, according to which all papal bulls and breves (authorizing letters) could be published only with his permission. A letter from Ferdinand to his viceroy in Naples, written in 1510, upbraids the viceroy for permitting the pope to publish a brief in Naples, threatens that he will renounce his own and his kingdoms’ allegiance to the Holy See, and orders the viceroy to arrest the papal messenger, force him to declare he never published the brief, and then hang him. In Spain the Catholic Monarchs had no formal right of exequatur, but they and their Habsburg successors behaved very much as if they did. From that time onward the Spanish clergy had to look to the crown and not to Rome for advancement, and so did the great nobles who traditionally claimed the richest ecclesiastical benefices for their younger sons. Perhaps most effective of all in reducing the political power of the high nobility was their virtual exclusion from the royal administration. The old royal council, a council of great nobles advising the king, was transformed into a bureaucratic body for the execution of royal policy, staffed by a prelate, three nobles, and eight or nine lawyers. These lawyers, mostly drawn from the poor hidalgo class, were entirely dependent on the royal will and became willing instruments of a more efficient and powerful central government. The Catholic Monarchs established the Council of Finance (1480, but not fully developed until much later), the Council of the Hermandad (1476-98), the Council of the Inquisition (1483), and the Council of the Orders of Knighthood (for the administration of the property and patronage of the orders of Santiago, Calatrava, and Alcántara), and they reorganized the Council of Aragon. After Isabella’s death in 1504, the nobles appeared to be tamed and politically innocuous. In fact, their social position and its economic basis, their estates, had not been touched. The Laws of Toro (1505), which extended the right to entail family estates on the eldest child, further safeguarded the stability of noble property. In 1520 Charles I agreed to the nobles’ demand for a fixed hierarchy of rank, from the 25 grandees of Spain through the rest of the titled nobility, down to some 60,000 hidalgos, or caballeros, and a similar number of urban nobility, all of them distinguished from the rest of the population, the pecheros, by far-reaching legal privileges and exemption from direct taxation. Thus, the Catholic Monarchs’ antinoble policy was far from consistent. Having won the civil war, they needed the nobility for their campaigns against the kingdom of Granada and, later, the kingdoms in North Africa and Italy. They now favored the nobles against the towns, allowing them to encroach on the territory around the cities and discouraging the corregidores and the royal courts from protecting the cities’ interests. Thus, the seeds were sown for the development of the comunero movement of 1520. Aragon Navarre These gradually expanded and eventually managed to defeat the Moors using their alliances. They ejected them from the Iberian Peninsula in 1492, when Isabella, heir to the throne of Castile, and Ferdinand II, king of Aragon, captured Granada, the last Muslim possession on the peninsula. After the final conquest of the last Moorish stronghold at Granada in 1492, Spain started financing voyages of exploration. Those of Christopher Columbus brought a New World to Europe's attention, and were followed by the Conquistadores who brought the native empires of Mesoamerica and the Inca under Spanish Control. At the same time, the Jews of Spain were ordered on March 30, 1492 to convert to Christianity or be exiled from the country. Through a policy of alliances with other European nobility and the conquest of most of South America and the West Indies, Spain began to establish itself as an empire. The Treaty of Tordesillas, negotiated by Pope Alexander VI between Portugal and Spain, effectively divided up the non-European world between these two budding empires. Massive amounts of gold and silver were imported from the New World into Spain's coffers. However, in the long run this hurt the Spanish economy much more than it helped it. The bullion caused high inflation rates, which undermined the value of Spain's currency. Additionally, Spain became dependent on her colonies for income, and when Queen Elizabeth I of England began to capture Spanish vessels on the way to and from the New World, Spain suffered massive economic losses. These effects, combined with the expulsion of Spain's most economically vital classes in the late 15th Century (the Jews and the Moors), caused Spain's economy to collapse several times in the 16th Century, bringing the Golden Age of Spain to a close. During the 1500s and 1600s, Europeans were much the same in the sense that these countries were looking to expand their economies and increase their prestige. It was this pride and thinking that motivated many of the superpowers of the world’s past. Two such monarchies in the European continent included England and Spain, which had at the time, the best fleets the world has ever seen. Because both were often striving to be the best, they remained in conflict with one another. Although England and Spain had their differences, they both had a hunger for exploration and it was this hunger that led them both to discovering different parts of the “New World” and thus, colonizing the Americas. The Spaniards arrived at the Americas prior to the English. The Spanish exploration was due to many factors the Black Death, population increase, and commerce. New strong monarchs sponsored the journeys for wealth and religion. In 1492, Spain’s Christopher Columbus attempted to go west to Asia, landing in today’s Cuba. The Spanish soon found the Americas a rich source of resources. A generation later, in 1518, Hernán Cortes arrived in Mexico with his conquistadors or conquerors. They sought gold. By using their military skills they took South America and made it a vast Spanish empire. Unfortunately, the Spanish unknowingly carried smallpox which decimated the indigenous populations. When they saw the sacrificial religious ceremonies of the Aztecs that produced many skulls, they thought of these people as savages and not entirely human. This of course may seem hypocritical because the Spanish had killed before and during the Inquisition for their faith, Christianity. Perhaps, it was the Aztec’s use of sacrificial religious ceremonies that led the Spaniards to believe it acceptable to decimate the natives. Spanish colonies were established when conquistadors obtained a license to finance the expedition from the crown and use encomiendas. Encomiendas were basically Indian villages that became a source of labor. The Spanish dreamed of becoming wealthier from South America, but they also wanted a profitable agricultural economy and to spread their Catholic religion. The Spanish empire came to consist of the Caribbean, Coastal South America, and Southern and North America. As the Spaniards moved northward in New Spain into New Mexico, the Pueblo Indians began converting to Christianity, which became very important by the 1540s. This meant expansion into the northern most areas of New Spain. New Mexico became a successful colony in 1599. However, as the Spanish demanded tribute from the local Indians. The Pueblos revolted in 1680 and drove the Spaniards out. The Spanish returned in 1696 and crushed the revolt. The colonial system of Spain was independent and more about financial ventures via contracts. However, later the monarchy of Spain made a hierarchical system in which the authority extended into the government of local communities and so colonists were not to establish any political institutions without the Crown’s consent. On the other hand, the British would be much less restrained. The English developed a system where the English queen played an unimportant role. There were also economic differences of what was to come with the English. The Spaniards were more about obtaining “treasure” from American colonies and therefore, they spent less time and energy on trade and agriculture which would prove to be less effective in the long run because the gold would eventually run out. Since the Spanish were very protective against piracy and only allowed only one colony ship to go through the Spanish ports and only two fleets to go to the colonies, economic development was hindered. Yet the English produced a larger amount of commercial products that would sustain their economy long after the gold and silver were reduced. Also in comparison, the British of North America concentrated heavily on permanent settling, family life, and also outnumbered the natives by far. Despite the diseases the Spanish inadvertently passed onto the native populations, the ratio of the Natives to Spaniards was much larger. The line between the Natives and the Spanish were less clear compared to that of the English because over time, men craved family and female companions and married natives, whereas in the English colonies, intermarriage was rare. England had other reasons to those of the Spanish to colonize. It was mainly average citizen and less explorer’s reasons for leaving Tudor England as it had gone through many costly wars and religious persecution (Queen Mary executed protestants and Queen Elizabeth then took that faith back) which left the people confused and doubting in their faith. Above all, it was the enclose movement (enclosing farm land together to boost economy) that took away farms from people leaving many without pay and or food. Another reason for leaving was so England could have a wider variety of commerce. Several merchant companies had already formed in monopolies, such as the East India Company of 1600. Investors made money from exchanging exotic products. By then, England followed mercantilism, which supported colonialism because the motto was to export a little and to gain a lot. Acquiring colonies was seen as getting necessities they would otherwise have to buy. Other people of England also supported colonies being established in the New world because they saw it as a simple yet, ingenious way to get rid of the superfluous, and at times, the poverty stricken population. Before the English settled in North America, they settled in Ireland. On the other hand, Spain primarily colonized the Americas. The English suppressed the Irish natives and because they did not understand their “primitive” ways, the English chose to stay separate from them. This concept was taken to the New World. Unlike Spain, the English tried to build their own society instead of ruling a foreign one. Under the leadership of Queen Elizabeth I and England’s nationalism that promoted expansion, Jamestown became the first permanent settlement in North America. Like the Spaniards, the colony was not achieved on the first visit to the New World. Sir Walter Raleigh, with the queen’s approval, established the state of Virginia (the virgin queen) and sent settlers to make a colony, which came to be named Roanoke. However, when a few of the men which had left for England returned in a few years, no one was found in the colony. It is still a mystery to this day what happened with the Roanoke colonists. It is theorized that the Indians murdered them because the English, like the Spanish, had also been cruel to the natives for the land. It is obvious to see that much of history would have been changed if it were not for the Age of Exploration. The seemingly economy driven expeditions of the English and the Spanish actually altered the face of the world because colonies were developed in which not only would be beneficial for money, but would also be called home for the next centuries to come for Europeans. The colonization of both Spain in South America and England in North America were alike in that both were done to secure a better productive commercial future but also because of the way they viewed the natives. They saw the “Indians” as inhuman beings and treated them unfairly. However, England and Spain hold many differences in terms of the New World as well. In the beginning, the Spanish conquistadores went strictly for gold and the fame of exploration. The Catholic Church was interested in the saving of souls. Later, Spaniards colonized and expanded their settlements. The latter were simply settling lands that were available and attractive for farming and ranching. The English civilians thought they would benefit if they left to go to a “Utopia”, as they heard of it. The English lived separately from the natives. Although there are many differences between the Spanish encomiendas and the English colonies, the basic idea of much cultural exchange is the same, for as it is seen, it is rare to see Native-Americans in North America and to see nonSpanish speaking people in South America. A change occurred in the 16th Century. Just as in the rest of Europe, the population of Spain grew, rising in Castile from about 4.25 million in 1528 to about 6.5 million after 1580. To meet the increasing demands for agricultural products, the peasants expanded the cultivation of grain and other foodstuffs, and the Mesta and its migratory flocks gradually lost their dominant position in the Castilian economy. Their contributions to government finances declined as a proportion of total government revenue. The growing market also stimulated urban industries. Segovia, Toledo, Córdoba, and other towns expanded their manufactures of textile and metal. The apex of this expansion was reached in the third quarter of the 16th Century, but it never matched that of Flemish and northern Italian cities. Overall, Spain remained a country that exported raw materials and imported manufactures. Charles I (Holy Roman emperor as Charles V) and Philip II were later to continue this work and to add further councils, notably those of the Indies (1524) and of Italy (1558). Spain's powerful world empire of the 16th and 17th centuries reached its height and declined under the Hapsburgs. The Spanish empire reached its maximum extent under Charles I, who was also (as Charles V) emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. Under his successor Philip II, rising inflation, the expulsion of the Jews and Moors from Spain, and the dependency of Spain on New World gold and silver combined to cause multiple bankruptcies and economic crashes in Spain. The riches of America were directed to pay the loans of European bankers like the Fugger that funded the costly wars in defense of Catholicism and the dynastic interests. Under Phillip II Spain also suffered the inglorious defeat of its Armada. As the Spanish Hapsburgs declined they ultimately yielded command of the seas to England. The Habsburg dynasty became extinct in Spain and the War of the Spanish Succession ensued in which the other European powers tried to assume control of the Spanish monarchy. King Louis XIV of France eventually "won" the War of Spanish Succession, and control of Spain passed to the Bourbon dynasty. Philip V, the first Bourbon king, of French origin, signed the Decreto de Nueva Planta in 1715, a new law that revoked most of the historical rights and privileges of the different kingdoms that conformed the Spanish Crown, unifying them under the laws of Castile, where the Cortes had been more receptive to the royal wish. Spain became culturally and politically a follower of France. The rule of the Spanish Bourbons continued under Ferdinand VI and Charles III. His son Charles IV was truly incompetent (some say mentally handicapped), and under his reign Spain fell to the armies of Napoleon. Under the Bonaparte’s, Spain failed to embrace the mercantile and industrial revolutions of the 18th Century, and also failed to absorb the ideals that of the Enlightenment that were revolutionizing European thought. These missed opportunities, combined with the economic failures of the 17th Century, caused the country to fall desperately behind Britain, France, and Germany in economic and political power. The war of Spanish Independence (1808-1812) was fought because of a Napoleonic invasion. This gave the opportunity to the American colonies to claim their independence, as England was otherwise engaged. In 1812 the Cortes took refuge at Cadiz and created the first modern Spanish constitution, informally named as La Pepa. This constitution was revoked by the returning king Ferdinand VII. 1820-1823 [Trienio Liberal] - After the pronunciamento (coup d'etat) by Riego, the king was forced to accept the liberal Constitution. 1823-1833 [Decada ominosa] - Another coup d'etat revoked the Constitution, executed Riego, and restored Ferdinand VII as an absolute monarch. By 1898, Spain had lost most of its colonial possessions. Then Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines and Guam were lost to the United States. (See also: Spanish-American War) Spain's colonial possessions were reduced to Spanish Morocco, Western Sahara and Equatorial Guinea. Mistreatment of the Moorish population in Morocco led to an uprising and the loss of all North African possessions except for the enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla in 1921. Abd el-krim, Annual. In order to avoid accountability, the king Alfonso XIII decided to support the dictatorship of general Miguel Primo de Rivera. The dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera collapsed in 1930. Disgusted with the king's involvement in it, urban population voted for republican parties in the municipal elections of April 1931. The king was forced to resign and a republic was established. Second Spanish Republic (1931-1939) was he first time women were allowed to vote in general elections. In this period, autonomy devolved to the Basque country and to Catalonia. Spanish Civil War 1936-1939 was caused by a right wing coup d'etat by Francisco Franco and other generals which started the Spanish Civil War against the Republic. The dictatorship of Franco 1936-1975 in Spain left her neutral in World Wars I and II. However, she suffered through a devastating Civil War (1936-39). During Franco's rule, Spain remained largely economically and culturally isolated from the outside world, but slowly began to catch up economically with its European neighbors. Under Franco, Spain actively sought the return of Gibraltar by the UK, and gained some support for its cause at the United Nations. During the 1960s, Spain began imposing restrictions on Gibraltar, culminating in the closure of the border in 1969. It was not fully reopened until 1985. Spain also relinquished its colonies in Africa, with Spanish rule in Morocco ending in 1956. Spanish Guinea was granted independence as Equatorial Guinea in 1968, while the Moroccan enclave of Ifni had been ceded to Morocco in 1969. The latter years of Franco's rule saw some economic and political liberalization, the so called Spanish Miracle, including the birth of a tourism industry. Francisco Franco ruled until his death on November 20th 1975 when control was given to King Juan Carlos. In the last few months before Franco's death, the Spanish state went into a paralysis. This was capitalized upon by King Hassan of Morocco, who ordered the 'Green March' into Western Sahara, Spain's last colonial possession. The transition to democracy 1975-1978 At present, Spain is a constitutional monarchy, and is comprised of 17 autonomous communities (Andalucia, Aragon, Asturias, Illes Balears, Islas Canarias, Cantabria, Castilla y Leon, Castilla-La Mancha, Catalunya, Extremadura, Galicia, La Rioja, Madrid, Murcia, Paes Vasco, Comunitat Valènciana, Navarra, Ceuta and Melilla). One of the most important problems facing Spain today is ETA's terrorism - this illegal organization defends Basque independence through violent means, which is condemned by both Central and Basque government, although there is tension between these governments since PNV (the party presently governing Basque Country) longs for greater autonomy from Spain, including the possibility of independence, something Spanish government doesn't accept.