Richtext.rtf

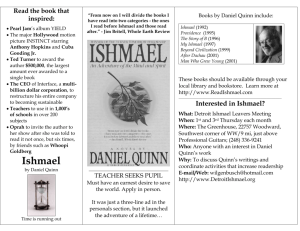

advertisement