RWD_Lecture_09

advertisement

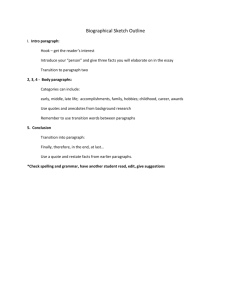

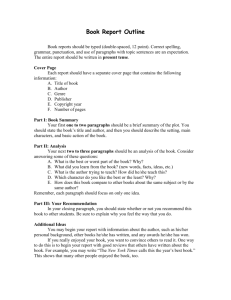

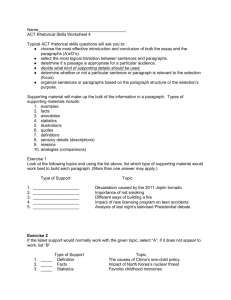

Lecture 9 THE CRAFT OF WRITING Lecture 9 LEARNING OBJECTIVES • to be able to use the macro/micro approach to writing • to appreciate the value of creative thinking • to know how to build strong, clear and well-linked paragraphs • to successfully structure a dissertation • to know how to correctly reference material in a dissertation Lecture 9 LECTURE OUTLINE • recommended reading • how to prepare and validate data • how to put data into an electronic form suitable for analysis Recommended reading: Chapter 10: The Craft of Writing, and Introductions and Conclusions, in the associated book: Horn, R. (2009) Researching and Writing Dissertations. London: CIPD Work-alone experiential activity: CONCLUSIONS Time allowed: 20 minutes’ preparation 3 minutes’ feedback Write three paragraphs that present the likely conclusions of your research. Feedback to the group: ‘I found that exercise easy/difficult because . . .’ Develop good writing habits: WRITING IS JUST LIKE ANY OTHER SKILL Writing is not a magical skill. It is a skill with a standard set of approaches and procedures that can be learned, and learned relatively quickly. So it is the same with writing – it can be learned but it takes some time and practice. Failure to spend time developing a writing style is a real shame because poor writing skills can weaken excellent ideas and research. Develop good writing habits: DEVELOP A WRITING HABIT Writing is a skill and skills must be practised. The best practice for writing is to write. Early in your dissertation there will be very few opportunities for writing large pieces of work. But you should get into the writing habit early. You can create opportunities for writing by reviewing, paraphrasing and critiquing some of the important theory in your subject area. Use feedback to improve your writing We are often very poor judges of our own writing. To enhance your skills in writing you have to overcome any reluctance to show your writing to others. Work-alone experiential activity: PRESENTATION AND FEEDBACK Time allowed: 60 minutes’ writing 30 minutes’ reading Write 500 words critiquing a theory your are likely to use in your research. When this is done, allow three other people in your group to read it and make comments about the writing. Reflect on the comments made. Develop good writing habits: UNDERSTAND THAT WRITING TAKES TIME Writing takes time, so you need to plan and organise carefully to ensure that you have enough time to carry out the writing and the reviewing process. Failing to provide the right amount of time to carry out the writing will lead to poor, rushed work. Typically, you will need about six to eight hours to complete (think, write and review) 1,000 words of academic writing. This assumes that you have done the background planning and research. Develop good writing habits: READ, THINK, DESIGN, WRITE AND REREAD EVERY DAY Writing, thinking, planning, reading, and rereading must become a daily habit when you are completing a dissertation. Unless you have carried out the reading of background material and have been thinking about that material, you will not have anything to write. By ‘thinking’ I mean understanding, critiquing, analysing, synthesising and evaluating. Once you have written a passage of work you must reread it to make sure that it is correct, makes sense and has clarity of thought and a strong argument. Try to set aside time every day for these tasks. Develop good writing habits: DEVELOP ‘STICKABILITY’ You may not have come across the term ‘stickability’ – it means the ability to concentrate on a task over periods of time, especially when the task seems to be getting increasingly difficult to complete. Stickability is a frame of mind. Successful people are often quite stubborn and will not be beaten by anything. This makes them difficult to live with, sometimes, but they do achieve things. Some people are naturally stubborn and stick at things. You may have to develop it! Develop good writing habits: THINK AND PLAN AND MAKE NOTES BEFORE YOU WRITE Macro writing is the planning that is done before you start to write. In a highly structured approach you would plan each chapter, section and paragraph before you started to write. This ensures that when you do write, the process is less daunting in that you simply extend each idea into a paragraph. You will have to develop and personalise your planning style but it is essential that you do plan, think and make notes before you start writing. Develop good writing habits: GET IT ‘WRITE’ FIRST TIME Following on from the idea of careful and extensive planning is the notion of writing structured, well-planned and evidenced paragraphs. This structured approach means that you are likely to write a paragraph that is ‘write’ first time. If you type first and think afterwards, you are likely to have to make extensive and time-consuming revisions. The quickest and most effective way to write is to think, plan, structure and organise – and only then write. Develop good writing habits: UNDERSTAND THE NECESSITY TO REVISE YOUR WRITING An idea forms in your head and is then transferred to type. While the idea may be well thought through and well evidenced, the writing process will always need review and improvement. You must plan a strategy for reviewing and revising your work. Once the words are typed, review each sentence in each paragraph before you go on, then review the whole paragraph. When you have read it several times and made corrections to: • English usage • the clarity of idea • the form of words, move on to write the next paragraph. Leave the writing for at least a week and then review whole sections and make revisions and adaptations. If you are able to enlist the help of someone else – friends, family, study group – let them read it and comment. MACRO WRITING Planning your macro writing can be done in various ways: • Make mental models in which each chapter and each subpoint is in a box, with paragraphs leading off the edge. Ordering the chapters and sections is carried out by numbering the boxes. • Use pen and paper to set out headings, subheadings and paragraph headings. Ordering the chapters is carried out by numbering and renumbering the headings and sections. • Use Word in outline mode. This allows for structured headings, subheadings and several levels below this. Ordering is done by position in the list, and reordering and reorganising is easy. Word in outline mode: HEADINGS This is a main heading – Heading 1 This is one heading lower – Heading 2 This is one heading lower – Heading 3 This is one heading lower – Heading 4 Word in outline mode: PLANNING • Chapter 2 – Introduction • Point 1 – Main point 1 • Introduction – paragraph • Main claim 1 – paragraph – Evidence for claim 1 • Main claim 2 – paragraph – Evidence for claim 2 • Point 2 • Point 3 • Conclusion of main point 1 Work-alone activity: ORDERING IDEAS Time allowed: 20 minutes’ preparation 2 minutes’ feedback Imagine that you have a literature review section that contains five significant theories. You have already decided that you will keep all five theories in the section but arrange them separately. Yet you cannot decide in which order to present them. It is a problem! The essence of the problem is to know what would be a logical way to organise these five theories. Ways you might organise them include: • historically – the earliest theory first • by complexity – the most easily understood first, leading finally to the most complex • by instrumentality – the most frequently-used theory in the literature comes first • by evaluation – moving from the least useful to the most useful. Feedback to the group: ‘My ordering would be . . .’ Work-alone activity: ORDERING A LITERARY REVIEW SECTION Time allowed: 20 minutes’ preparation 2 minutes’ feedback You are now ordering the ideas for each theory. You have the following points that you want to make, but you are not sure of the order in which to write them: • critique of the theory: three main critical elements • evaluation of the theory • research studies that have used the theory as the main research guidance • description of the theory • advantages of the use of the theory to understand business research • limitations of the theory in understanding business research • practical uses of the theory in management • description of a related theory developed from the first theory. Create a logical order for these points so that they build into a strong argument. Feedback to the group: ‘My ordering would be . . .’ CREATIVE THINKING Creative thinking might be thought of as the ability to generate something new. In your dissertation there will be endless opportunities to create and use new ideas. This is a vital part of the dissertation process, but one that is often forgotten or ignored, leading to rather dull and onedimensional writing. The ideas that we are looking for in a dissertation are not brilliant, astonishing ideas – they are good, sound ideas for solving problems, creating new theory, using an existing idea in a new way, adapting an existing method to work better in your research. Creative thinking: CREATIVE EVOLUTION Creative evolution uses an existing idea to develop a better one. Small refinements in methods and theory can generate useful new ideas. Solutions to existing organisational problems can often be refined and improved and used in your dissertation. Research methods are a useful area to consider creative evolution. Published research methods were designed for a different context from that of your research – don’t be afraid to engage in creative improvement of a method so that it works better with your context and research questions. Creative thinking: CREATIVE SYNTHESIS Synthesis is the combining of things to create something new. This can be very useful in developing theory, methods, data analysis, and solutions. Try bringing ideas from other subject areas and applying them in business. Creative thinking: CREATIVE REVOLUTION Creative revolution throws away old ideas and asks ‘What about the impossible?’ When you are looking for a creative revolution, you do not need to think about what has been used before – only about whether something will work. If your data presents a research problem, finding a creative revolution would require asking many ‘What if . . . ?’ questions. ‘What if we . . . ? Or what if we . . . ?’ In this way you should try out lots of improbable ideas or solutions until you have a eureka moment. This would be the equivalent of ‘brainstorming’ ideas. Creative thinking: CREATIVE REAPPLICATION Creative reapplication involves looking at something old in a new way. Clear your expectations of how old ideas can be applied, and opportunities open up. Try to look at your dissertation outcomes in new ways and look for new solutions based on existing solutions. Reapplication in dissertations works well with theory, methods, and solutions. Creative solutions and breakthroughs occur when we stop trying to implement a solution and start trying to find a solution. Paragraphs: UNDERSTANDING THE STRUCTURE A paragraph tends to develop a single idea, statement, finding or line of argument. A series of paragraphs forms a section or a chapter. Try to adopt some of the following ideas related to paragraph use: • Vary the lengths of paragraphs to maintain the reader’s interest. • Try to avoid very short, one-sentence paragraphs. • Avoid long paragraphs – there should be a minimum of four or five per page of single-spaced text. Any longer than this and the reader will get lost and you will lose their attention. • Paragraphs should have a natural ‘flow’. Paragraphs: UNDERSTANDING THE STRUCTURE In a paragraph: • The first sentence introduces the paragraph. • The main points follow on. • The last-but-one sentence summarises the paragraph. • The final sentence links to the next paragraph, and or the overall theme of the section or chapter. • Use link words and phrases such as ‘although’, ‘in contrast’, ‘however’, ‘but’, etc. • Vary your use of common words to avoid monotony. Try to aim never to use the same word twice in any one sentence, and no more than three to five times in any one paragraph. Paragraphs: STATEMENT, ANALYSIS AND FINDINGS PARAGRAPHS In dissertations many paragraphs will be introducing and evidencing statements, analyses and findings. These paragraphs will need a particular structure: • Paragraph statement (introduction) • The main claim or statement of the paragraph • FIRST EVIDENCE to support the claim or statement • Warrant – how the evidence supports the claim or statement • Qualification of the evidence (exceptions and anomalies) • SECOND EVIDENCE SOURCE • THIRD EVIDENCE SOURCE, and maybe up to five or six more sources of evidence • Summary sentence • Link sentence to a new paragraph. Work-alone activity: PARAGRAPH DESIGN Time allowed: 30 minutes’ preparation 2 minutes’ feedback Carry out the ‘Practice in analysing’ paragraph exercise to be found on page 231 of the recommended reading text. Feedback to the group: ‘My paragraph is . . . And my reflections on this writing are . . .’ LINKING AND SIGNPOSTING To improve the clarity of your writing it is important to provide links and signposts. Sentences, paragraphs, sections and chapters can all be linked. Aim to provide extensive links between sentences and paragraphs, and to a lesser extent sections and chapters. Paragraph links are often provided in the first and/or last line of a paragraph. Linking and signposting: FORWARD-LINKING Paragraph links are often provided in the first and/or last line of a paragraph. The last line of a paragraph can link forward – for example (the unwritten meaning is in brackets): 1 ‘However, this was not the only issue related to gender’ (there is another coming up in the next paragraph). 2 ‘Some issues remain to be resolved in this data’ (and are explored in the next paragraph). 3 ‘This evidence brings up some striking points that as yet we have not discussed’ (but we will be doing so soon). 4 ‘However, although these points make a compelling argument in favour, there are counterpoints that ought to be explored’ (the counter-argument is in the next paragraph). Linking and signposting: BACKWARD-LINKING The first line of a paragraph can conversely link backwards – for example: 1 ‘Although we have seen the evidence of a gender-based pattern of behaviour, there is evidence and data that does not support this position’ (and is in this paragraph). 2 ‘Although most of the data relates to quantitative measures, we also investigated some qualitative elements (which are coming up in the current paragraph). 3 ‘There are weaknesses in the argument above that need further exploration’ (which is forthcoming in this paragraph). Linking and signposting: SIGNPOSTS ‘Signposts’ are a mark of good writing and help the reader to understand the argument more easily. They also provide a sense of where the reader is in the text. The signpost is created with words and phrases such as: for example, . . . however, . . . similarly, . . . some problems with . . . in contrast, . . . this programme . . . despite this counterevidence, . . . this suggests . . . however, in future research . . . in the following section . . . the next chapter will look at . . . in the last chapter we looked at . . . whereas this was covered there, that will be covered here . . . a recent study reported ... the seminal work in this area was . . . In each phrase there is a link to something already mentioned or that will be mentioned. Signposts can work at various levels, from sentences and paragraphs to sections and chapters. DISSERTATION STRUCTURE The general structure of a dissertation is like this: Title page Title, your name, course name, date, name of supervisor Abstract One paragraph summarising the whole dissertation Acknowledgements Thanks to those who have assisted you Table of contents Chapters and/or sections and subsections with page numbers Table of figures and illustrations DISSERTATION STRUCTURE Introduction A presentation of your question/problem/thesis, the context in which the research was undertaken, and a brief outline of the structure of your work Main chapters: Literature review Methodology Data collection Analysis of data – how Findings from the data – what Conclusion/findings Here you bring it all together, restating clearly your main findings, making recommendations, suggestions, and revisiting and evaluating how well you met the research objectives DISSERTATION STRUCTURE Bibliography A complete list of your sources, in alphabetical order and correctly formatted Appendices Any relevant information not central to your main text – for example, complete questionnaires, copies of letters, maps, etc Other sections you could be asked to include might comprise: • terms of reference • reflective accounts • executive summary • skills development matrix DISSERTATION FORMATTING Formatting your dissertation submission, the following list of recommendations should be followed: Use A4 paper (or whatever is the standard size in your part of the world). Provide a front cover for your dissertation with the title centred about one-third of the way down the page, your own name centred about six lines below, your supervisor’s name six lines below that, and with the university name about six lines below that. Leave a margin of at least 3 centimetres at the sides and top and about 5 centimetres at the bottom for the marker’s comments. Use a font size of 11pt or 12pt. Use either Times New Roman or Arial. The requirement for dissertations is that they are printed in double-spacing. But because of environmental concerns, many universities will accept single-spacing. Align the page on the left only – do not fully justify the text. Separate paragraphs with a blank line between them. After a full-stop leave (only) one space before the capital letter of the next sentence. Do not accidentally leave extra spaces between any of the words. Ensure that your pages are numbered using Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, etc). Do not number your points or paragraphs – this is report form and is not suitable for a dissertation. Work-alone activity: CASE STUDIES: Alison and Tonna Time allowed: 180 minutes’ preparation 5 minutes’ feedback Read both case studies ‘Alison’ and ‘Tonna’, and provide structures for a literature review and a findings chapter, as requested at the end. Feedback as two separate structures. Work-alone activity: REFLECTION Preparation for the next learning session Prepare two PowerPoint presentation slides setting out: • your experience of reflection to date • who you intend to get help from in completing your dissertation REFLECTION on the learning points of this lecture • Try to develop effective writing habits • Spend time designing and planning your writing – macro writing • Try to bring creativity to your writing • Develop sound ways of constructing paragraphs • Make extensive use of linking and signposting • Ensure that you use an appropriate structure and format your dissertation appropriately