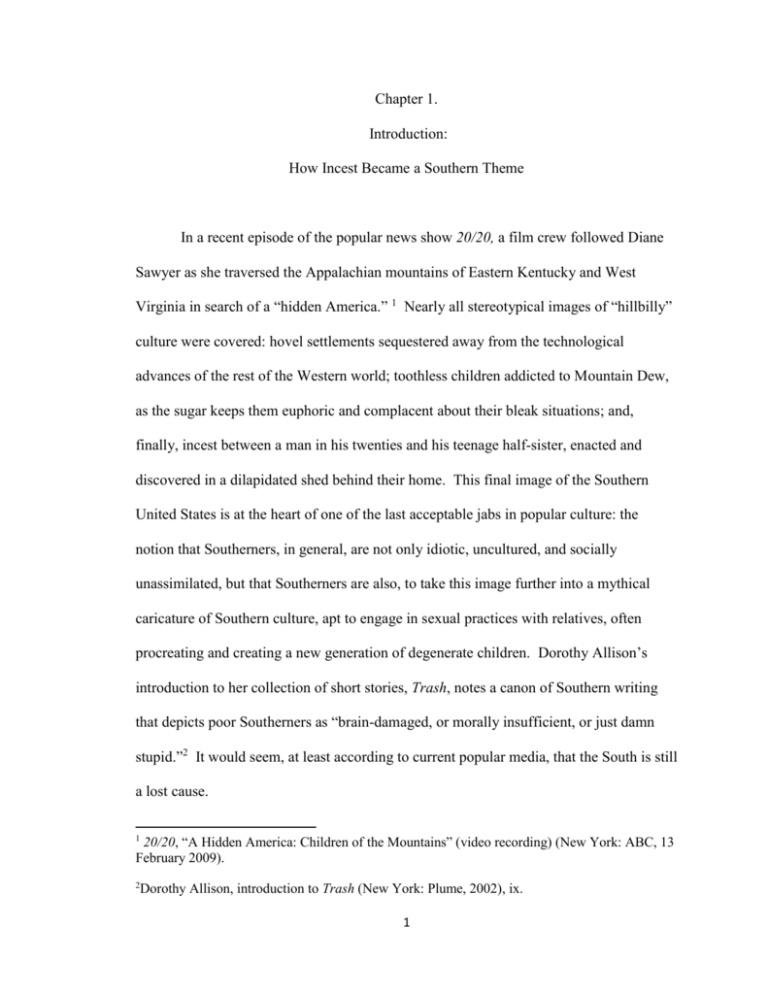

Chapter 1.

Introduction:

How Incest Became a Southern Theme

In a recent episode of the popular news show 20/20, a film crew followed Diane

Sawyer as she traversed the Appalachian mountains of Eastern Kentucky and West

Virginia in search of a “hidden America.” 1 Nearly all stereotypical images of “hillbilly”

culture were covered: hovel settlements sequestered away from the technological

advances of the rest of the Western world; toothless children addicted to Mountain Dew,

as the sugar keeps them euphoric and complacent about their bleak situations; and,

finally, incest between a man in his twenties and his teenage half-sister, enacted and

discovered in a dilapidated shed behind their home. This final image of the Southern

United States is at the heart of one of the last acceptable jabs in popular culture: the

notion that Southerners, in general, are not only idiotic, uncultured, and socially

unassimilated, but that Southerners are also, to take this image further into a mythical

caricature of Southern culture, apt to engage in sexual practices with relatives, often

procreating and creating a new generation of degenerate children. Dorothy Allison’s

introduction to her collection of short stories, Trash, notes a canon of Southern writing

that depicts poor Southerners as “brain-damaged, or morally insufficient, or just damn

stupid.”2 It would seem, at least according to current popular media, that the South is still

a lost cause.

20/20, “A Hidden America: Children of the Mountains” (video recording) (New York: ABC, 13

February 2009).

1

2

Dorothy Allison, introduction to Trash (New York: Plume, 2002), ix.

1

While there are those widely admired figures of the South—for example,

television host, restaurateur, and food celebrity Paula Deen—much of their fame relies on

their ability to keep reinforcing the quaintness of the Southern character. Juxtaposed with

this image is the opposite representation: the pervading notions of a degenerate South

comprise the bulk of visual representations of the region. Even those projects like the

20/20 documentary that work under the guise of “bringing awareness” to the cause do not

fully encompass the immediacy of the issues in that community. To return to the final

image of the man who sexually abuses his half-sister, we do not learn the fact that over

one third of Appalachian region high school sophomores, college students, and young

women studied by the Journal of the Appalachian Studies Association reported

involvement in an incestuous relationship.3 We do not learn that because of the

mountains and the harsh, long workdays, women are often sequestered away from one

another,4 making it all the more difficult to address the real concern of sexual abuse

within this violent and disenfranchised region. This is where the media representations

fail us: their visions of the South as a sort of wild, still self-contained, self-policed,

backwards, and degenerate place have undermined the truths of the victims of the abuse.

For the media, their work represents a half-truth: yes, the South is still many of the things

listed above, yet the victims of sexual abuse become inevitable players in this grotesque

staging of Southern existence. We accept that the South is backwards, so we do not

question that this abuse occurs, nor do we offer, as is the case in the 20/20 documentary,

any strategy for speaking about and quelling this problem. Despite the obvious real-life

Peggy J. Cantrell, “Family Violence and Incest in Appalachia,” Journal of the Appalachian

Studies Association 6 (1994): 39-47.

3

4

Kathy Kahn, Hillbilly Women (New York: Doubleday, 1973), 21.

2

manifestations of these overblown stereotypical representations—many of which posit a

willing incest partner as the norm—the majority of incest victims in the South are not

complicit in the act. Even despite the focus here on the southeastern region, the problem

is of a much larger national concern. According to RAINN—the Rape, Abuse, and Incest

National Networks—one out of every six American women has been the victim of an

attempted or completed rape.5 Though these numbers do not attend to incest specifically,

they do speak to an already overwhelming problem with sexual abuse in this country.

RAINN also notes that 15% of sexual assault and rape victims are under the age of

twelve.6 This fact underscores the added concern that many victims are assaulted before

they are even of an age that is psychologically, cognitively, and emotionally familiar with

the basic facts of sexuality. When one considers that juvenile victims of sexual abuse

know their attackers in 93% of these incidents,7 the likelihood of incestuous abuse among

Americans is much higher than what exists within the stereotypical attachment the term

has to the South. These numbers can only account for the known or spoken cases, as

incest is an abuse that often goes unreported due to shame and, in some instances,

allegiance to one’s family unit.

Where incest jokes about Southerners abound, another individual is desensitized

to the reality of the fact that real victims experience traumatic abuse behind these vulgar

representations, and not only in the Southern United States does incest occur. Could it be

RAINN, “Who Are the Victims?,” Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network,

http://www.rainn.org/get-information/statistics/sexual-assault-victims (accessed August 20,

2009).

5

6

Ibid.

7

Ibid.

3

that jokes and popular culture representations of incest have made this often abusive act

seemingly predictable to the point of creating social complacency? Greg Forter attends

to these everyday traumas that do not carry the same “punctuating” effect of the distress

outlined in trauma theory studies. Instead, these traumas have become normalized, he

argues, as we are shocked by major traumatic events, such as the Holocaust or even a

widely reported rape case;8 it is the individual cases rendered impotent by sensational

images that posit the victim as seductress, or, on the opposite end of the spectrum, the

victim becomes complicit in an act perceived to be commonplace in the South.

Rather than to suggest that all stereotypes of incest attached to the South are

unfounded, I argue instead for the perusal of literary representations of the abuse that

create complex portrayals of a real-life crisis. If incest abuse is a problem in the South—

as it is all over the United States and the world—then how will merely dismissing these

real victims as fodder for crude humor ever change this unfortunate cycle? Southern

women’s writing works beyond the popular culture myth that portrays a willing incest

party or a sensationalized, poor, and without-agency victim and gives voice to the

voiceless abused; those, who in real life are shamed away from speaking about their

abuse, now have a platform for speaking. Granted, these are still the voices of literary

characters and not real victims speaking within the text, yet many of the protagonists of

these novels were created by authors—such as Dorothy Allison, Gayl Jones, and Kaye

Gibbons—who were themselves victims of sexual abuse.

While all of these images are familiar to a broader American audience, due in part

to the perpetuation of this representation of the South in popular media, it is the incest

Greg Forter, “Freud, Faulkner, Caruth: Trauma and the Politics of Literary Form,” Narrative 15,

no. 3 (2007): 260.

8

4

stereotype that fully encompasses the degrading nature of what it means to live in the

Southern United States in the twenty-first century. For a region that so hyped its

commitment to honor—despite its incongruous actions against humanity—leading with

this decidedly dishonorable image of the South creates a cultural dissonance within its

people. At its finest, if mythic, representation, the South produces genteel people of a

long and familiar heritage; they are dangerously devoted to their stock and their way of

life. These are the pleasant folk of amiable race relations in films about maternal black

maids raising gentle and precocious white children and each speaking in exaggerated

honey tongues. The converse, however, is a South built on the exploitation of “lesser”

bodies—women, minorities, and animals, to name a few—and somewhere in the middle

of these images, both holding true for ages of Southern history, the image of the

degenerate Southerner—poor, xenophobic, and disenfranchised—became the

overwhelming face of a South, that, at least in popular film and media, still remains

unchanged. It is this latter image that most often is linked with incest, which then

becomes the brunt of crude humor, where all forms of sexual depravity are connected

with an already despondent region.

If the image stops here—as it does in 20/20’s “A Hidden America”—then the

camera pans out from that final blow to Southern culture: the realization that there are

poor pockets in rural America where people have created a unique social code based on a

fear of the outsiders that once capitalized on their land, seduced the poor with promises of

money, took advantage of their lack of educational and social resources, and dug

violently through their land to create the coal mines that offered an opportunity for

capitalist gain but at the cost of the workers’ bodies. These same outsiders—who were

5

often from the North and looking to bypass strict Union laws9—brought discord with

their poor working conditions in the textile factories they set up on the edge of the

mountains. Though “A Hidden America” does reference a sample of this history, it also

reinforces the pitiful reality of Appalachian life—and remember that we are speaking of

the “trashy” and not the genteel South—where, inevitably, one might find the most

backward practice of all: incest. It is from this truth that the film crew backs away, packs

up, and stamps the project complete. Where do we go from here? What are we to do

with this knowledge? To find the positive revisioning amidst sensationalized victim

tropes of abuse in the South, victim ridicule in popular culture humor, and the national

dismissal of a region that is viewed as so far gone there could be no return, I look to the

contemporary Southern women writers who use individual victims’ voices as a means to

counteract the “normalizing” effect of popular culture representations of the Southern

United States. These women writers’ ability not only to represent but also to transmute

the experience of incest abuse without further denigrating the cultural learning of its

people both reinforces and dispels Southern myths; at the same time, they create a space

for women writing about women, as traditional incest discourse has been spoken,

represented, regulated, and circulated by males, despite the fact that most incest crimes

have, traditionally, been committed by men against women.

The “kissing cousins” myth in Southern culture that illustrates consensual incest

exists, in part, due to fact. At one point in Southern pre-Civil War history, as many as

9

Kahn, Hillbilly Women, 9-10.

6

one in eight Southern couples were related,10 and only a little over half of Southern

marriages had no relation at all.11 Consensual incest, which does not involve the abuse of

a child and occurs between two adults of close blood relation, distant blood relation, and,

in some instances, can be denoted by a relationship that is familial in nature—in-laws and

step-siblings engaging in sexual relationships, for example—is the kind of incest upon

which crude, in-bred humor is made. Though interfamilial blood need not be necessary

for the depiction of incest practices in the South—even in-law sex or step-sibling sex

would be taboo—it is often the most feared type of incestuous behavior, as this union can

breed the horrifically familiar yet unpredictable: what has already been bred is now

doubled, and, therefore, reduced. (Think of the declining quality of a copy of a copy of a

copy.) Though there is a law in all fifty states to prevent incestuous marriage and/or

sex,12 there is no hard evidence to suggest that there is a higher incidence of consensual

familial sexual practices in the South. Still, it is certainly not WASP-y East Coast culture

that is typecast as the perpetrator of incest. It is not the elegant crowds of wine country

that intermingle blood so salaciously, nor is it the cultured New Englanders, the earthconscious of the Pacific Northwest, the desert dwellers of the Southwest, or even the

mountain folk of the Rockies that are stereotyped as degenerate violators of natural order.

Kathryn Lee Seidel, “Myths of Southern Womanhood in Contemporary Southern Literature,”

in The History of Southern Women’s Literature, ed. Carolyn Perry and Mary Louise Weaks

(Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2002), 436.

10

11

Bertram Wyatt-Brown, Southern Honor: Ethics and Behavior in the Old South (Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 2007), 220.

“Inbred Obscurity: Improving Incest Laws in the Shadow of the ‘Sexual Family’,” Harvard

Law Review 119, no. 8 (2006): 2465.

12

7

With the exception of rural Maine and Alaska,13 and even despite the frequently rural

living conditions of Midwestern America—which is generally referred to as

“wholesome”—it is primarily the Southerner’s lot to carry this burden of backwardness.

Incest cases that are nonconsensual—the abusive incest that involves a minor and

is illegal in all states14—are the tales linked with the poor, and, consequently, depraved

people of the South. That is, although incest occurs within both middle and upper class

families in and outside of the South, the preferred portrayal is that of a poor family’s

sexual deviances, for these are the victims most easily sensationalized and forgotten, if

ever heard at all. It is difficult to gauge the states with the highest incidents of incest, for

there is no way to account for the silence that cloaks this taboo topic. Though the

Southeast is home to more than a third of the nation’s population, it would seem

impossible to associate the bulk of incest cases directly to this region. As there is no

evidence to indicate any correlation between incest cases and their prevalence in the

South, the mythical, backwards, depraved Southern family is instead reiterated as truth

with no supporting statistics. It is manifestations, such as “A Hidden America’s” tired

account of the poor “hillbillies,” that reinforce the notions of a South with hidden sexual

depravities at every twist and turn without attending to the socioeconomic, psychological,

geographical, or personal concerns of the abused and the abuser. The “we told you so”

13

Maine, because it is the most rural and sparsely populated state east of the Mississippi River,

often has an incest stigma attached to its people for the same reasons incest is connected with the

Appalachian region. Alaska, especially after the last presidential election where outlets like

Saturday Night Live created anti-Sarah Palin jabs via derogatory incest skits about the state, is

also predominately rural and, like Maine, sequestered on the edge of the country. These rural

locations coupled with less white collar industry have made the stigma, though not nearly as

prominent as that attached to the South, a relatively common association.

14

Ibid.

8

moment for the producers occurs when incest abuse is revealed as the final component of

Appalachian life. The show exploits one girl’s victimization as a dramatic conclusion to

the grotesque perusal of all things “backwards.” Those victims of incest abuse in the

South barely have an outlet for their voices, save for the sensationalized dramas of

primetime television fame. Then again, linking this abuse to one region—and especially

incest’s association to the South with all of its historical misdeeds—undermines the

reality of the incestuous abuse that occurs in varied family units across this nation.

Unlike the crude kissing cousins jokes, victim incest carries an even darker

stigma. Despite all of the other images of degeneracy that are linked with the South—

slavery, limited educational opportunities, lower standards of living, a self-imposed

refusal to unionize workers, a higher incidence of divorce, obesity, and smoking, little

regard for the environment and the land, and a higher prevalence of animal cruelty—

incest is, quite possibly, the most degrading stigma of all. For this region that has so

often been linked with backwardness and stagnancy, the perpetuation of this image

further mars the area’s cultural legacy. The incest myth underscores the inert nature of

the Southern region, for, as Richard H. King mentions, “to choose incest is to attempt the

primal repetition which culture forbids. It is to stop or reverse time, to undo what has

been done, to unravel the social fabric, and to regress to the pre-social.”15 Certainly the

South has a reputation for isolating and even reversing social advancements in the United

States, but just as recently as 2009, another report of long-term incest abuse emerged with

the discovery of an Australian man accused of raping his daughter for the last thirty years

15

Richard H. King, A Southern Renaissance: The Cultural Awakening of the American South,

1930-1955 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982), 126.

9

and fathering four children with her.16 This horrific tale of incest abuse mimics that of

Austrian Josef Fritzl, who also locked away and raped repeatedly his daughter, fathering

seven children over numerous years of abuse.17 Both stories occurred outside of the

South, which proves that this need to control and stop the progression of natural order—

to own and thwart the sexual health of one’s offspring—can and does occur anywhere.

Yet, as it is in both cases, there are no Australian or Austrian incest myths or stereotypes.

The popular culture representation of the South’s link to incest, however, does not

approach the topic with disdain for the incest that is often practiced against one’s will,

nor does it attempt to understand or delve into the origins for this oft-repeated image.

Instead, the Southern incest stereotype is regurgitated in such outlets as the HBO show

True Blood, which is based on the Southern Vampire Series by Charlaine Harris.

Protagonist Sookie Stackhouse admits to her first lover, Bill, a member of the attemptingto-integrate vampire population in fictional Bon Temps, Louisiana, that she was sexually

molested as a girl by her uncle. 18 Sookie, a working-class waitress in an intolerant

Southern town, has already committed a social taboo by entering into a relationship with

a vampire, which carries the stigmatic weight of an interracial relationship in the South—

which is still somewhat forbidden both in the Southeast and across the United States—

and contemporary culture’s admonishments against gay marriage. The flashback of

Sookie’s abuse is interspersed with Sookie’s naked form as she sits in a bathtub post“Australia Father Faces Rape Trial,” BBC News, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/8260412.stm

(accessed April 12, 2010).

16

Matthew Weaver and Kate Connolly, “Josef Frizl Admits Abduction and Fathering Daughter’s

Children,” Guardian , http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/apr/28/austria.internationalcrime2

(accessed April 12, 2010).

17

18

True Blood, “Burning House of Love” (video recording) (New York: HBO, 19 October 2008).

10

coitus with Bill. Sookie’s uncle’s words, “Her tiny little legs…so flexible and

smooth…,” introduce the stylized molestation montage juxtaposed with Sookie’s bare,

adult body, as the inevitable “come sit on my lap” scene concludes. The camera does not

discern, nor does it allow for the cognitive recognition of what is inappropriate and what

is appropriately erotic. Both versions of Sookie—the violated child and the highly

sexualized woman—have melded into a single image of an individual doomed to relive

her abuse for the remainder of her adult sex life. We, the viewer, passively explore

Sookie’s juvenile abuse and consensual seduction intermittently. Southern stereotypes of

backwards rural folk, jovial race relations, ignorant and masculine redneck men all

accompany this quintessential incest tale that ineffectively attends to the victim’s need for

anonymity. Instead, she is on display, wrapped in a tale delivered by actors overexaggerating their accents. It is a stylized South, and the incest subplot only renders what

could be useful dialogue completely impotent. Sookie has again, as it would seem, been

violated.

Though the eroticization of incest stories abounds in popular culture and Southern

literary heritage, it is the representation of the backwoods Southern degenerate,

procreating less-than-perfect children along with his close kin that is most often repeated.

In a 1998 episode of the comedy series Frasier, the title character’s ex-wife returns to

town and has sex with her ex-brother-in-law, Niles. Afterwards, the horrified, snotty,

bourgeoisie Niles remarks, “These things happen. They happen every day—everyday in

Arkansas!”19 Though the two are not blood relations, and the marriage that made them

in-laws has since dissolved, the implication is that they have done something utterly

19

Frasier, “Room Service” (video recording) (New York: NBC, 3 March 1998).

11

immoral, and only in the South would something so reprehensible and socially

unacceptable be deemed appropriate. This stigma extends beyond the occasional comedy

show critique, as even former Vice President Dick Cheney, while still in office, furthered

this stereotype in June 2008, when he made an off-color remark about incest in the state

of West Virginia.20 Other images of Southern degeneracy come straight from high

culture Southern literary heritage, such as Erskine Caldwell’s God’s Little Acre, where a

Southern patriarch attempts to own and sexualize every female member of his extended

family in a grotesque portrayal of land, ownership, and legacy, and in James Dickey’s

Deliverance, whose book, and the later film that followed, have inspired the shirt,

“Paddle faster—I hear banjos”; these images underscore Southern backwardness (though

not directly a story of incest) in one of the most readily familiar stories of Southern

ineptitude.21

Other representations still complicate these commonly held notions of Southern

corruption. In the first season of Dave Chapelle’s provocative comedy series Chappelle’s

Show, Chapelle plays a fictional black man that is a white supremacist from the South

named Clayton Bigsby. Bigsby is blind and therefore not aware of the fact that he

represents the very thing he abhors.22 Bigsby tells the news reporter following his story

that his friend, Jasper, told the black man that came to the house to date his white sister:

“Cheney Makes Incest Joke about West Virginians,” The Huffington Post, June 2, 2008,

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/search (accessed October 11, 2008).

20

Minrose Gwin, in her article, “Nonfelicitous Space and Survivor Discourse: Reading the Incest

Story in Southern Women’s Fiction,” also remarks on the popular culture perpetuation of

backwardsness in the Appalachian community and other parts of the South where Deliverance

models are frequently connected to the Southern United States as an example of Southern

degeneracy. This is where literary fiction becomes fact for many Americans.

21

Chapelle’s Show, Episode 101 (video recording) (New York: Comedy Central, 22 January

2003).

22

12

“That there’s my girl. Anyone have sex with my sister it’s gonna be me.” Chapelle’s

spot-on analysis of race is often satirized in his clever play on stereotypes, so it is no

surprise that he effectively attacks the Southern disdain for interracial relationships but

also attends to the stereotype of incestuous Southern siblings. Further complicating this

image is the 2008 film Harold and Kumar Escape From Gauntanamo Bay, which works

to dispel several myths, including that of the geeky, hyper-successful Asian man, the

African-American street thug, and the uncouth Southern hick.23 As the lead characters

Harold and Kumar run from the law officials that have wrongly implicated them in a

terrorist plot, they find refuge in the home of a camouflage-clad Southern man. The

home’s façade is the expected trailer surrounded by rusted cars, but the interior is

decorated with tasteful, contemporary designs. The man’s wife is a pleasant and

attractive hostess who enjoys reading and fine cuisine. During dinner, Kumar says, “You

know, this is good guys. I kind of always assumed people from the South were….” His

male host interrupts indignantly with, “… a bunch of dumb rednecks? We do try to keep

our inbred son in the basement when we have company…,” but he and his wife erupt in

laughter, presumably because this image is so preposterous. Later, however, the inbred

toddler appears with one eye in the center of his head, as grotesque evidence of the

Southern myth turned fact. Both of these overtly twisted portrayals of incest, in and of

themselves, take the myth of the Southern inbred to an outlandish and thereby obviously

fictional level, while the surrounding myths that are portrayed and dispelled also render

impotent the notion that any single person, or even any region, can be classified within

the confines of a typecast.

“Dinner Guests,” Harold and Kumar Escape From Guantanamo Bay, DVD, directed by Jon

Hurwitz and Hayden Schlossberg (Burbank, CA: Warner Home Video, 2008).

23

13

Despite all of the contemporary representations, the link between incest and the

South is certainly nothing new. Even before Faulkner’s Quentin Compson, steeped in

melancholy, longed for his own sister and idealized the Southern sisters of those before

him, incest was a reality in the Old South. As Peter Bardaglio discusses, countless court

documents reveal a changing relationship with this seemingly taboo topic, while the term

itself was twisted and compressed to fit the specific case on the docket. The rules

concerning incest—whether the act was forced or consensual—were often determined

based on the rules of the Bible, which amassed all women under the same laws of

ownership applicable to cattle, chattel, and land. Evidence of the power white men held

over women in the Old South is supported by the fact that “over four-fifths of incest cases

that appeared in Southern high courts during the nineteenth century…involved older men

accused of carrying out incestuous relations with subordinate female relatives who were

considerably younger.”24 As one judge deemed the case of incest a “subject of great

delicacy and pervading interest,”25 the court proceedings for this violation became more

like a public showing of the accused and his victim, which rarely came to justice for the

sake of maintaining genteel pretense and because of the South’s pervasive belief that

family affairs should be policed within that unit. Women barely had any agency in these

court proceedings, though they were sometimes held accountable for their own abuse

under the notions that they incited the violence. Jean E. Friedman notes that despite the

fact that men were accused of crimes far more often, they were charged with minor

Peter Bardaglio, “ ‘An Outrage Upon Nature’: Incest and the Law in the Nineteenth-Century

South,” in In Joy and Sorrow: Women, Family, and Marriage in the Victorian South, 1830-1900,

ed. Carol Bleser (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), 39-40.

24

25

Ibid., 41.

14

infractions—“drinking, dancing, disorderly conduct”—while women were accused of

sexual offenses and got a harsher punishment.26 Even if women did try to fight back in

these hearings, they were often punished further for stepping out of place. Victoria

Bynum remarks that it was the women in the Old South who were neither “wives nor

slaves to white men” that had the hardest time coming to justice.27 With this unprotected

status, under which fell sisters, cousins, nieces, daughters, and basically every woman

that did not carry the legal status of spouse or slave, countless abusive acts likely never

even made it to the court systems.

The South became more influenced by outside industrial and cultural influences

during the Reconstruction period from 1865-1877. This declared the Confederacy an

illegal entity and freed the slaves that were already the ethnic majority in some Southern

states. An already pervading fear of outsiders was reinforced during the Southern

Renascence of the 1920s and 1930s. As part of this tradition, Faulkner’s characters

create a sentimental visioning of a South longing to keep its legacy within family bounds

at all costs. Though Faulkner himself does not romanticize the incestuous bonds that

often occur within his texts, his characters reveal a pervading sense of family loyalty to

the point of xenophobia. In Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom!, first published in 1936,

Quentin Compson is the voyeur gawking at a Southern past that decries many of his own

anxieties about keeping tabs on the chastity of the Southern woman. Quentin’s lesson

from his father—“Years ago we in the South made our women into ladies…Then the war

Jean E. Friedman, “Women’s History and the Revision of Southern History,” in Sex, Race, and

the Role of Women in the South, ed. Joanne V. Hawks and Sheila L. Skemp (Jackson, MS:

University Press of Mississippi, 1983), 7.

26

27

Victoria E. Bynum, Unruly Women: The Politics of Social and Sexual Control in the Old South

(Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1992), 89.

15

came and made the ladies into ghosts”28—underscores the character’s belief that one

must take direct and extreme measures to return those Southern women back to a time

before the ghost-making occurred. In essence, Quentin must recall a pre-war error,

before the insertion of foreign, Northern bodies. He must return to a time before the

freeing of slaves, which also contributes to his Southern white male fear of outsiders. For

those Southern men who swore to protect, under Southern honor codes, their wives,

mothers, and sisters, the infiltration by Northern troops and free black men made them

feel their women could be more easily stolen and defiled. It threatened their stance as

ultimate guardian of their female clan’s chastity. As he listens to Rosa Coldfield detail

the rise and eventual fall of Thomas Sutpen, Quentin relates to siblings, Henry and Judith

Sutpen’s, complicated family dynamic. Like his own tormented relationship with his

sister Caddy, detailed in Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, Quentin learns that Henry

and Judith had a relationship “closer than the traditional loyalty of brother and sister.”29

When both become infatuated with the mysterious Charles Bon, it seems the perfect

union will be sanctioned by Judith’s marriage to Bon, thus making his admirer and best

friend, Henry, his family. Not until the fact that Bon is Thomas Sutpen’s mixed son is

revealed—thus making him Henry and Judith’s half-brother—does the horror of their

situation come to a head. Still, it is the miscegenation and not the incest that so bothers

Henry and eventually moves him to murder Bon for the sake of honor. As the siblings

are so close, their affection for Bon is shared—it mirrors one another—and they are both

victims of his unintentional seduction. The horror of their situation is only compounded

28

William Faulkner, Absalom, Absalom! (New York: Vintage International, 1986), 7.

29

Ibid., 62.

16

further, even beyond this double incest account, as Bon is a stranger for his mixed race

and for the fact that Judith had yet to even see him before she fell in love via their

correspondence: “…that single personality with two bodies both of which had been

seduced almost simultaneously by a man whom at the time Judith had never even seen”30

Faulkner’s Absalom becomes the ultimate tale of incest and fear of foreign bodies.

Though his work is freely associative, Faulkner’s would-be voice of the cultured South

underscores what would become decades of incest tales connected with the Southern

region.

Like Henry Sutpen’s offspring, Quentin’s obsession for his own Southern sister,

Caddy, mirrors Henry and Judith’s complicated bond. It is these hallmark stories of the

South that create a cultural Catch-22: Faulkner carved a place for the South in high

culture, but much of this came at the cost of reproducing the worst of this region within

tales of incest, which is one of the most degrading attributes of all. Still, southerners

embrace these tales. They are proud of this twisted heritage at the same time that they are

tired of being the bastard child of America. In many ways, incest as a Southern theme

begins here, and though we can say modern and popular culture took these texts—and the

historical facts that predate the literature—and ran with them, it is Southern writers

themselves, such as writers clearly exhibiting Faulkner’s influence (e.g., Walker Percy

and Reynolds Price), who have further perpetuated these images in melancholic, romantic

texts of a bittersweet Faulknerian South.

It would be several decades, however, before Southern women’s writing would

take an honest, nonromantic approach to the South that cuts the sentimentality woven

30

Ibid., 73.

17

throughout Faulknerian Southern Literature. The genteel exterior is stripped, and the

plight of the working class victims of incest abuse comes to the forefront. As incest, or

any other sexual indiscretion, for that matter, would not have been good form for early

Southern women writers, it would be decades before the real story of incest was

reproduced in Southern women’s writing. Jacquelyn Dowd Hall comments that Southern

history, at least the tales that do get told, was at a detriment when it came to female

writers and the depiction of Southern women’s history, as “the South has not been

notable for training and supporting female scholars.”31 Further, those who did get

educated often moved away after or during their education.32 Finding and keeping

female scholars interested in and writing about the region was a concern for many years

until the Women’s Rights Movement brought the issue of incest to the forefront. Judith

Herman and Lisa Hirchman’s seminal feminist study on the topic of incest, “FatherDaughter Incest,” which first denounces Sigmund Freud’s own belief that incest could

not exist so often as it was reported and especially not in “respectable families,” 33 was

one of the first texts to deal with incest as a violation, rather than as a cultural

phenomenon or as a reaction to a child’s own seductive qualities. I do not suggest that

Faulkner’s work directly reinforced the patriarchal myth that women who were abused

incited the violence against them; rather, Faulkner’s writing is somewhat complicit in its

overtly sentimental visioning of its tainted women. For example, Caddy in The Sound

Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, “Partial Truths: Writing Southern Women’s History,” in Southern

Women: Histories and Identities, ed. Virgina Bernhard et al. (Columbia, MO: University of

Missouri Press, 1992), 12.

31

32

Ibid., 12-13.

33

Judith Herman and Lisa Hirschman, “Father-Daughter Incest,” Signs 2, no. 4 (1977): 737.

18

and the Fury was never literally abused, but her sexual deviance tarnished her family

after her brother, Quentin, failed to “save” her. Just like those early Southern courts that

further victimized the victim, no one fully attended to the need for a book about the face

behind the sensationalized images of the “damaged” girl.

Those Southern writers, and in particular, contemporary, Southern women

writers, who have worked to create a genre for nonvictimizing, frank discussion of incest

abuse have been criticized for jumping on the latest literary trend of realist texts about

childhood sexual abuse.34 In her article for Harper’s, Katie Roiphe asserts that the

“current trend” of incest writing “blew north from the hot porches of Southern

literature.”35 For a region that has maintained niceties for the sake of “honor,” how is it

that a topic like incest could become a tenet of the genre? At one point, Faulkner’s lofty

exploration of incest was one of the only Southern texts exploring the theme. It was not

until the 1970s Women’s Rights Movement cultivated feminists who left the South and

sought education in other places outside their region that the reality of sexual abuse in the

South came crashing out of the wings; these tales blew the lid off the incest secret that

creates a double victimization: the initial abuse and the shame that follows, often forcing

victims to self-censor their trauma. This only goes double for the Southern region, where

gentility and honor still linger around church corners in small towns, forcing “unsavory”

topics back into the closet.

34

Katie Roiphe, “Making the Incest Scene,” Harper’s, November 1995, 65.

35

Ibid., 68.

19

Roiphe comments on several texts where, as she claims, incest was used as a

crude marketing ploy meant to scintillate and entice.36 Writing under a tradition of texts

based around incest abuse, such as Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, Dorothy Allison’s

Bastard out of Carolina, Gayl Jones’s Corregidora, and Alice Walker’s The Color

Purple, Roiphe mocks the scenes where the abusive act is recounted in what she

describes as “pornographic precision.”37 If Roiphe’s sensibilities are so insulted by these

private acts of incest portrayal—meaning that these depictions of incest abuse are kept

quiet within the confines of the text—how might she respond to the theatrical productions

that also produce dialogue about incest but now move to the public domain? Plays such

as Carson McCullers’s The Member of the Wedding, Naomi Wallace’s In the Fields of

Aceldama, Marsha Norman’s Getting Out, Paula Vogel’s How I Learned to Drive, and

Lydia Diamond’s stage adaptation of Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye all must confront

the daunting task of creating a dialogue about incest without, themselves, becoming the

violators.

Connected beyond mere thematic similarities is the fact that the aforementioned

texts are all works of Southern writing. Some of the authors were born and raised in the

South, while others merely move fluidly in their writing throughout the boundaries of the

Southern United States, but each connects the turmoil of this region with the much more

private tragedy of incest within the Southern family unit. Where earlier texts by male

Southern writers romanticized the forbidden desire between parent and child or

siblings—think again of Quentin Compson who broods not only over his own taboo lust

36

Ibid., 65.

37

Ibid., 67.

20

for his sister Caddy in Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury but also valorizes the love

triangle between siblings Henry, Judith, and Charles Bon in Absalom, Absalom!—later

Southern women’s writing portrays the traumatic effects of a practice that nearly became

second nature for a doomed region. I wish to illustrate the reasons why incest—in

practice, in history, in literature, and even in crude humor—is oft-linked with the South.

Further, I argue that despite writers like Roiphe, who incorrectly assumes these female

narratives on incest abuse are mere selling tactics, there is still a place in both the private

and public sphere for the portrayal of incest abuse.

Southern history supports the notion that both literal incest, which is defined by a

sexual violation of blood relation, and figurative incest, marked by the abuse at the hand

of a father figure or through a suggested but never physically enacted relationship

between blood relatives, was not an uncommon practice. Therefore, incest became an

accepted norm in an environment where plantation owners sexually exploited generations

of their own offspring, and, as Bertram Wyatt-Brown’s study of the Southern “code of

honor” argues, that dominant Old South ethics, which were based on a rigid adherence to

family hierarchies, undying duty to that same unit, and an obsessive need to maintain

tradition to the detriment of the South’s own people, was more prevalent in Southern

society than any other group of the time; yet this “honor” often backfired as it bred the

very things it sought to eliminate: “unjustified violence, unpredictability, and anarchy.”38

The aftermath of this antebellum code of ethics has affected the work of its cultural

offspring. It cannot be erased over time; so, too, do the Southern writers, even years after

38

Wyatt-Brown, Southern Honor, 61.

21

the abolition of slavery and the breaking down of formal honor codes, work under a

heavily signified tradition.

Southern writers cannot write within a vacuum, nor can they ignore the historical

significance of this tormented region if they wish to be grounded firmly within the

Southern genre. But what makes something a Southern theme? Around 1860, as the

South’s secession began with South Carolina—when the chasm between the North and

the South became indelible—the South’s proclivity towards cultural xenophobia was

further compounded. Now an entire region was sequestered away from the United States

based, at least in part, on the moral premise that using bodies for the purpose of unpaid

labor, to perpetuate one’s clan, and to gain personal capital was not a human atrocity.

This already wavering moral code further blurred the boundaries between appropriate and

inappropriate sexual acts, such as incest, which was admonished by the book of Leviticus

in the Bible but now became a necessary practice due to rural limitations on socializing,

fear of foreign takeover—including that of “Yankee” bodies—and a steady adherence to

patriarchal norms. This practice within the Southern family structure placed female

bodies, like black bodies, under the category of ownership. Patricia Yaeger’s Dirt and

Desire connects the genre of Southern literature directly to the theory that it is a

collection based on ownership—who owns what and whom.39 Nowhere is this ownership

more apparent, and, perhaps, more dire, than in the incestuous violation of one’s own

relatives. This fact coupled with Charles P. Roland’s “The Ever-Vanishing South,” in

which he argues that Southern Literature as a genre can never be severed from its history,

stresses the importance of ancestry and roots for the Southern writer:

Patricia Yaeger, Dirt and Desire: Reconstructing Southern Women’s Writing, 1930-1990

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 13.

39

22

One could never say of a novel by Faulkner what C. Vann Woodward has said of

the work of a famed twentieth-century nonsouthern writer, Ernest Hemingway:

that is, ‘A Hemingway hero with a grandfather is inconceivable’… Southern

fiction swarms with grandfathers, grandmothers, great-grandfathers, and greatgrandmothers, and so on ad infinitum.40

With regard to this statement, starting with Southern history only seems natural.

Locating the real stories before looking at the fictional depictions is key for finding the

nonromanticized and non-idealized versions of incest. The issue here is to discern

wherein incest ceased to be a behind-closed-doors act within a family unit and

transformed into romanticized chivalry.

Incest has also become a common tenet of the Southern literary field for several

“incestuous” practices that are commonly connected with the Southern United States.

This includes the Southern practice of nepotism, an institutional incest of sorts, which

approves and hires professors from the pool of individuals that were educated within that

same institution. Southerners are also less apt to move away from home and the family

that binds them. Unlike other regions of the country, Southerners foster an indelible

connection to those of blood relation far more than other areas of the country. The

largest and most prevalent religious denomination in the South, the Southern Baptists,

continues to advocate a patriarchal order and even went so far as to amend their rules at

the 2000 convention to include specific guidelines banning women from leadership—

basically, vocal and influential positions—in the church.41 This denomination that is so

Charles P. Roland, “The Ever-Vanishing South,” Journal of Southern History 48, no. 1(1982):

12.

40

“Southern Baptist Convention Passes Resolution Banning Women as Pastors,” New York

Times, June 15, 2000, sec. A, 22.

41

23

influential on Southern social and political practices works to undermine more equal

status for women within the Southern family while also counteracting the move for frank

and open discussion about sexual impropriety. As stated above, Southern courts in the

Old South were distrusting of victims’ accounts of incest,42and this culture of victimizing

the victim continues to prevail in many Southern regions. Even a group like the Ku Klux

Klan, which was founded in Pulaski, Tennessee, in May 1866, points to a pervasive fear

in the South of anything that does not seem homegrown or local, for the group’s mission

to exterminate what they perceived as outside threats—a fear of black bodies violating

white female bodies was the primary rationale behind lynching—is indicative of a dark,

Southern need to maintain purity within its women, create ethnic order, and uphold

patriarchal structures. Despite the advances in the cosmopolitan South—Atlanta,

Georgia, being the flagship of this new vision of the region—this desire to separate and

regress, to defend and protect, and to self-police without federal government interference

still manifests within the South’s most current rulings: the recent amendments to ban gay

marriage; a law that would allow gun-permit holders to bring their weapons into all

establishments where gun carrying is currently banned, including restaurants that serve

alcohol and state parks; and a push for English-only laws in several large cities across the

region. All of these things coupled with a society that was slow to educate women or to

offer contemporary feminist perspectives within its institutions meant that the abuse that

did occur in the South was never formally challenged with a useful feminist discussion of

the fact for decades.

42

Bardaglio, “‘An Outrage Upon Nature,’” 50.

24

Whether stated explicitly or subtly, incest in various manifestations is inextricably

bound with the work of Southern writers, and, in particular, it abounds in Southern

women’s writing throughout the twentieth century. Though the incest myth is based in

fact, it is my task to find the origins of this location. As the various popular cultural,

mythical Souths that are most often reproduced continue to appear in contemporary

media, simultaneously, there is a literary heritage in the South that frequently includes the

reality of incest abuse, and, at its core, is a tradition of contemporary Southern women

novelists and playwrights dedicated to making certain that these stories are told and

retold. Despite admonitions against this so-called “literary vogue,” I argue that it is not

only possible to reproduce the incest tales of the South without further underscoring that

image of the morally inept South of modern media scrutiny, but also it is necessary. My

primary criticism is of Roiphe’s article, mentioned earlier, as I refute the notion that all

texts concerning incest are ploys to create sensationalized and thus, profitable, literature.

Roiphe’s “Making the Incest Scene” argues that human nature’s proclivity towards

viewing gruesome acts inevitably undermines the incest convention. She asks, “Is the

subject of incest inherently cheap? Not necessarily. But the situation itself is so extreme

that it grabs our interest with very little skill on the part of the writer—like a murder or a

car crash, it jolts us into the story. As the father reaches under his daughter’s nightgown,

we can’t help but be fascinated.”43 Her belief that this “pornographic” material has no

capability for feminist transformativity is false. Roiphe’s assumption that all writers that

create depictions of incestuous sexual abuse are simply catering to the human desire for

what is depraved and, thus, pleasurably disturbing, is just as problematic as telling

43

Roiphe, “Making the Incest Scene,” 67.

25

victims of incest that they should remain silent for fear of disrupting society’s

sensibilities. I, instead, argue that numerous female depictions of incest within Southern

literature effectively point to decades of hidden secrets in Southern culture that were, and

still are, put into place by strict adherence to patriarchal family norms. These Southern

women writers feel attention must be paid; we can no longer ignore the crime, nor keep

the act close like a secret, or even induce shame in the victims by having them believe

that something like incest abuse could never be spoken.

In response to Roiphe’s claims, Naomi Klein imagines Roiphe’s own sensational

writing for the purpose of profit, as her controversial article was released, strategically, to

“shock the virtually unshockable modern reader.”44 Her position that Roiphe’s

antifeminist strategies make Roiphe even more astounding than the works against which

she rails precisely underscores the admonishments I have personally received since the

inception of this topic. Against those admonishments, I assert the following: Incest

should be written; it should be spoken; and it should not be limited to the private confines

of the novel, but, rather, it should be liberated as far as to even create depictions for the

stage for the purpose of public discussion and, possibly, if writers achieve the intended

goal, work to bring about strategies for change. Further, incest depictions should not be

limited to degrading or satirical jabs at the Southern region, for they do not fully

encompass the wide-reaching concern of incest abuse across the nation and across the

world. Despite the more likely tendency for Southern writers to take up the topic of

incest, it should not be limited to these writers alone to carry the burden of incest

portrayal.

Naomi Klein, “Humiliation of the Shock Jocks,” Toronto Star, November 18, 1995, second

edition, H5.

44

26

Karen Jacobsen McLennan’s book, Nature’s Ban: Women’s Incest Literature,

spans nine centuries of women’s writing about incest. She argues that the collection and

redistribution of these particular works is necessary to show how the authors “interweave

their perilous knowledge of incest into the culture’s literary tradition, thus creating the

possibility for witnesses to banned knowledge. Readers find language in place of

secrecy, knowledge in place of denial, and feminism in place of submission.”45 In

essence, McLennan’s anthology not only allows an avenue for these voices, creating her

own terms and rules for distribution and organization, but also accomplishes the act of

setting up a community of women’s writing about the abuse that otherwise double

victimizes in its initial act and again in its forcing of the victim into near-debilitating

shame after the fact.

Because I have chosen to stay within the framework of incest portrayals within

Southern Literature texts, I am interested in why this particular topic has become a

common theme within the genre. For example, why, as stated earlier, does the inclusion

of incest within a piece automatically make an ambiguously rural text decidedly

Southern? Is this merely a stereotype perpetuated by the Faulknerian model of Southern

literature, or is it, instead, founded in the fact that numerous incidences of incest within

Southern families were common, documented practices? Could it also be due to the fact

that institutional slavery and the South’s slow-to-industrialize society slowly assimilated

to changing trends in patriarchal family structures? Necessary to this study will be a

close examination of incest in the text and on the stage and how the two are dissimilar in

their private/public depictions.

Karen Jacobsen McLennan, ed., “Introduction,” in Nature’s Ban: Women’s Incest Literature,

ed., Karen Jacobsen McLennan (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1996), 7.

45

27

Incest as a Southern theme has become both a literary and dramatic convention,

but to understand why this theme must be revisited, I turn to the therapeutic components

of trauma theory. Southern female writers examine the deep-rooted effects of a region

dealing with the aftermath of sexual abuse that manifested and became part of the culture

in a time when all but white males had no agency in the society. Further, the patriarchal

practices of plantation life firmly cemented the power of the Southern white male’s will

over all that he owned. This practice still manifests in many ways in the South; the

South’s upholding of the patriarchal order can be located within even the seemingly most

innocent contemporary practices, such as father-daughter purity balls, which are

Evangelical Christian-based events that are enacted as a formal ceremony—often like a

wedding, as the daughter wears a white gown and takes vows—where fathers escort their

daughters and receive a ring as a symbol of her virginity. The father gains ownership

over her chastity, while the daughter can “collect” her ring only after her wedding night.

In essence, she never owns her sexuality. It is passed from father to husband in much the

same way antebellum Southern daughters were passed from their father’s homes to their

husbands. Though many would argue that this ceremony in no way relates to the

traumatic effects of incest, it does illustrate the unabashed display of patriarchal agency

over the female sex that still exists within contemporary Southern society, where the bulk

of purity balls take place. Even in an era of post-second-wave and third-wave feminism,

these events are gaining ground, and new purity balls happen every year, though there is,

as of yet, no equivalent event to contain and control the son’s chastity. It is in this

society’s climate where judgments about victims of sexual abuse are double-victimizing.

Further, if victims of sexual abuse do speak out to the point of making their abuse a legal

28

case, thereby making the act public, they often must testify to the fact that they did

nothing to provoke the abuse, that they did not actually want the abuse, and that they

conducted themselves and wore the appropriate clothing so as not to entice their abuser.

If the sexual abuse is incest, then the victim is even further traumatized because the

sexual act becomes more of a social taboo, often inciting uncomfortable feelings within

many of its witnesses. How can we empathize, then, if we cannot stand to listen?

In this way, incest becomes more than a localized problem for one individual or

even one family unit; instead, it is a shared trauma that has plagued the Southern region

for decades of silence or has been reinterpreted in miscommunicated accounts that depict

incest as a necessary and chivalrous practice. This is one of the key components that

separates incest in Southern texts from other literary genres: Southern men could justify

their actions based on social honor codes and Bible-sanctioned rights. Incest victims’

traumas cannot fully be comprehended without the process of revisiting the abuse, which,

in turn, effectively elicits empathy within its witnesses. In her introduction to Trauma:

Explorations of Memory, Cathy Caruth views trauma as a “repeated suffering of the

event, but it is also a continual leaving of its site.”46 In this manner, the writing and

performance of incest becomes a necessary and holistic act. Laub, in his study of trauma

in Holocaust survivors, mentions the need for survivors to speak the truths of their

history. Without the unencumbering effect of releasing oneself from these traumatic

truths, one cannot know the “buried truth in order to be able to live one’s life.” 47 For

Cathy Caruth. “Trauma and Experience: Introduction,” in Trauma: Explorations in Memory,

ed. Cathy Caruth (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 5.

46

Dori Laub. “Truth and Testimony: The Process and the Sruggle,” in Trauma: Explorations in

Memory, ed. Cathy Caruth (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 63.

47

29

Laub, the speaking and witnessing of one’s trauma—for him, it was the Holocaust, and

here it is the survivor of incest abuse—must occur lest the act still live and grow every

day within its host. Laub further argues that the Holocaust had no witnesses, as the very

people who encountered these acts were continually exterminated to the point of creating

non-entities even within the surviving victims.48 I would argue that this claim extends to

victims of incest abuse, as they are “exterminated” by the shame that keeps them from

speaking out about their abuse, their lack of access to a sympathetic ear, and by the

images of a degenerate South—the toothless, dirty children of news documentaries, the

degenerate kissing cousins, and the hyper-sexualized Southern girl—all erase the real

faces of incest abuse. Imagine if we all took Roiphe’s claims of incest text

sensationalization. If not in Southern women’s writing, then where do we locate the

“appropriate” space for these victim accounts?

In all of these depictions that link incest to the Southern region—television

shows, crude humor, documentaries, movies, books, plays, and everything in between—it

is the women writers in this genre who have most effectively carved out a new Southern

region where none of these truths are inevitable, where Southern history can be written

and explored without shame, where personal experience becomes of public concern, and

where the South actually can rise again but as a region that is working to reverse the

wrongs that garnered our stigmatization in the first place. As we reap what we sow, so,

too, will we sow what we wish to reap for future representations of the changing South.

48

Ibid., 65-66.

30