Digital Representation of Audio Information

EE513

Audio Signals and Systems

Digital Signal Processing (Analysis)

Kevin D. Donohue

Electrical and Computer Engineering

University of Kentucky

Spectra

The spectrum of the impulse response indicates the following filter/system properties:

resonance and frequency sensitivities through the magnitude spectrum

delay and dispersive properties through the phase spectrum.

The discrete Fourier transform (DFT) computes complex samples of the spectrum.

For deterministic signals both the phase and magnitude are important for characterizing the signal or response.

For stationary noise processes the square of the DFT magnitudes can be averaged from independent segments to create a power spectral density.

Discrete Fourier Transform

In order to take a DFT of a signal, a finite window (time interval) must be extracted from the original sampled time signal:

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

-0.2

-0.4

-0.6

-0.8

3.2

3.4

3.6

3.8

4 4.6

4.8

5

1000

800

600

400

200

4.2

Samples

4.4

5.2

x 10

4 0

-0.5

-0.4

-0.3

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.4

0.2

-0.2

-0.1

0 0.1

Hz (Normalized Fs = 1)

4

3

0.2

2

1

0 0

-0.2

-1

DFT Phase

-2

-0.4

-3

-0.6

4.34

4.345

4.35

4.355

4.36

4.365

4.37

4.375

4.38

4.385

4.39

-4

-0.5

-0.4

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0 0.1

0.2

Samples

Hz (Normalized Fs = 1) x 10

4

The process can be repeated with overlapping windows covering entire signal.

0.3

0.4

If the signal is deterministic and changes over time, the DFTs for small consecutive intervals must be displayed to show the changes in spectrum over time (Spectrogram).

If the signal is random with statistics that do not change over time, the DFT magnitudes can be averaged (Power Spectral Density (PSD)).

0.5

DFT and Inverse DFT

DFT points are evaluated at discrete frequency samples

(frequency sampling). The DFT for an N point sequence is defined as:

N n

1

0 x ( n ) exp

jn

2

k

N

for 0

k

N

This inverse DFT is a similar computation to the DFT except the complex conjugate of the kernel is used: x

1

N

1 N k

0

( k ) exp

jk

2

n

N

for 0

n

N

DFT with W notation

Let W

N equal the complex sinusoid with the lowest nonzero frequency ( k = 1):

W

N

exp j

2

N

W

N is effectively a fundamental frequency in a harmonic expansion, since the frequency domain is sampled in equal increments. DFT and its inverse can now be written as:

X

ˆ

N n

1

0 x

(

n

)

W

N kn

for 0

k

N x

1

N

N k

0

1

X

ˆ

(

k

)

W

N

nk

for 0

n

N

Computation Examples

Compute the DFT for the 4 point and 8 point signals given below:

x ( 0 ) , x ( 1 ) , x ( 2 ) , x ( 3 )

0 , 1,1 , 0

x ( 0 ) , x ( 1 ) , x ( 7 ) 0 , 1,1 , 0, 0 , 0, 0, 0

What was the effect of extra zeros padded on the end of the signal in the second example?

150

180

W

2

4

= -1

210

120

Computation Examples

IM

90

W

3

4

= j

60

Compute the DFT for the 4 point

0 , 1,1 , 0

30

W

0

4

= 1

0

RE

330

X

ˆ n

3

0 x ( n ) W

4 kn for 0

k

4

240

W

2

4

= -j

270

300 k

0 , X

ˆ n

3

0 x ( n ) W

4

0

0 W

4

0

1 W

4

0

1 W

4

0

0 W

4

0

2 k

1 , X

ˆ k

2 , k

3 , X

ˆ

3 n

0

3 n

0 x ( n ) W

4

1 n x ( n ) W

4

2 n

0 W

4

0

1 W

4

1

1 W

4

2

0 W

4

3 j

1

0 W

4

0

1 W

4

2

1 W

4

0

0 W

4

2

0

3 n

0 x ( n ) W

4

3 n

0 W

4

0

1 W

4

3

1 W

4

2

0 W

4

1

1

j

2

135

2

135

Computation Examples

W

5

8

=

2

2

150

1

120 j

180

W

4

8

= -1

W

3

8

=

210

2

2

1

j

240

90

W

6

8

= j

270

W

2

8

= -j

60

W

7

8

=

30

2

2

1

j

Compute the DFT for the

8 point

X

ˆ n

7

0 x

0 , 1,1 , 0, 0, 0, 0, 0

( n ) W

4 kn for 0

k

8

W

0

8

= 1

0

330

300

W

1

8

=

2

2

1

j k

1 , X

ˆ k

2 , X

ˆ k

0 ,

n

7

0 x ( n ) W

8

0

0 W

8

0

1 W

8

0

1 W

8

0

0 W

8

0

0

2

n

7

0 x ( n ) W

8

1 n

0 W

8

0

1 W

8

1

1 W

8

2

0 W

8

3

0

.

71

j 1 .

71

1 .

85

67 .

5

n

7

0 x ( n ) W

8

2 n

0 W

8

0

1 W

8

2

1 W

8

4

0 W

8

6

0

.

1

j

2

135

k

3 , k

4 , k

5 , X

ˆ k

6 , X

ˆ

n

7

0 x ( n ) W

8

3 n

n

7

0 x ( n ) W

8

4 n

0 W

8

0

1 W

8

3

1 W

8

6

0 W

8

1

0

.

71

j 0 .

29

0 .

76

157 .

5

0 W

8

0

1 W

8

4

1 W

8

0

0 W

8

4

0

0

n

7

0 x ( n ) W

8

5 n

0 W

8

0

1 W

8

5

1 W

8

2

0 W

8

7

0

.

71

j 0 .

29

0 .

76

157 .

5

n

7

0 x ( n ) W

8

6 n

0 W

8

0

1 W

8

6

1 W

8

4

0 W

8

2

0

1

j

2

135

k

7 , X

ˆ n

7

0 x ( n ) W

8

7 n

0 W

8

0

1 W

8

7

1 W

8

6

0 W

8

5

0

.

71

j 1 .

71

1 .

85

67 .

5

Computation Examples

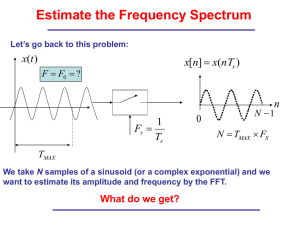

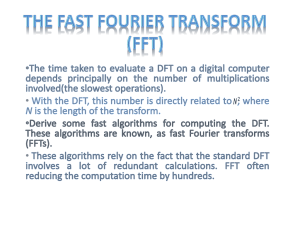

What symmetries exist in the W

N factor in the DFT computation that suggest a more efficient computation than a direct multiply and summation? The implementation that takes advantage of these symmetries is called a Fast Fourier

Transform (FFT).

If the sequence is a power of 2, the FFT is most efficient.

A direct implementation of the DFT requires N 2 complex multiplications. An FFT requires Nlog

2

N complex multiplications.

Compute the ratio between complex multiplications for the

FFT and DFT for a 128 point sequence. Compute the same ratio for a 2048 point sequence.

See http://www.cmlab.csie.ntu.edu.tw/cml/dsp/training/coding/transform/fft.html

For more details on the FFT derivation

Homework(1)

Derive each of the symmetry relationships below for the

W

N

factor:

W

N k

W

N

N

k

for N

1

W

N nk

W

N k

( N

W

N

N

2 n

W

N k

) k

*

for for N any n ,

k

1 , and

and N

N even

1

W

N nk

2 n

1 N

0

W

N nk

N

*

W

N

2 nk for any n , k

, N

N for any k

, N

1 and N even

1

Frequency Sampling, FS to DFT

Time sample the following FS equations to show it equivalence to the DFT.

x ( t )

k

X

ˆ

[ k ] exp( j 2

kf o t ) for x ( t )

x ( t

T ), T

1 f o

[ k ]

1

T

T

x ( t ) exp(

j 2

kf o t ) dt

Sample time axis with T s where NT s

= T

1

0.5

0

-0.5

-1

0

1

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

0

1

DFT Harmonics (N=4)

x(n) with kernel for k= 0 x(n) with kernel for k= 1

1

0.5

0

-0.5

-1

0 1 2

Samples x(n) with kernel for k= 2

3 4 1 2

Samples x(n) with kernel for k= 3

3

1

0.5

0

-0.5

-1

0

2

Samples

3 4

1 2

Samples

3

4

4

1

0.5

0

-0.5

-1

0

1

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

0

1

0.5

0

-0.5

-1

0 2 x(n) with kernel for k= 0

DFT Harmonics (N=8)

x(n) with kernel for k= 3 x(n) with kernel for k= 6

1 1

2 4

Samples x(n) with kernel for k= 1

6

0.5

0

-0.5

8

-1

0 2 4

Samples x(n) with kernel for k= 4

6

0.5

0

-0.5

8

-1

0 2 4

Samples x(n) with kernel for k= 7

6

1

0.5

0

-0.5

8

-1

0

1

0.5

0

-0.5

8

-1

0 2 4

Samples x(n) with kernel for k= 2

6 2 4

Samples x(n) with kernel for k= 5

6 2 4

Samples

6

1

0.5

0

-0.5

8

-1

0 4

Samples

6 2 4

Samples

6 8

8

8

FFT Spectral Estimates

Distortion and error result from the truncated and frequency sampled signal because:

Lost energy from truncated time portion will distribute error over the signal.

Truncating signal at the endpoints can introduce a sharp transition that may not be part of the signal.

Sampling signal in frequency produces periodicity in time, which results in circular time-domain convolution from multiplying spectra in frequency domain.

Frequency Sampling Effect

The DFT can be applied to a finite duration signal. If signal support is infinite, part of it must be truncated. The DFT definition is applied to the finite number of points to obtain a frequency sampled spectrum, which results in a periodic extension of the signal in the time window.

Sampled signal for DFT analysis

0.2

0

-0.2

-0.4

-0.6

-0.8

1

0.8

0.6

0.4

-1

0

Truncate Signal 30 Seconds

5 10 15 20 25 30

Time in Seconds

35 40 45 50

Sampled signal for DFT analysis

0

-0.2

-0.4

-0.6

-0.8

-1

0

1

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

Truncate Signal 150 Samples

50 100 150

Time in Sample Index

200 250

Frequency Sampling Effect

The DFT representation implies the time domain signal was periodic (sampling in time produces periodic spectra, likewise sampling in frequency produces periodic time segments) as would be the case for Fourier series.

1

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

-0.2

-0.4

-0.6

-0.8

-1

-150 -100

Periodic Extension from Frequency Sampling

-50 0

Original

150 point signal

50 100 150

Time in Sample Index

200 250 300

Circular Convolution

Multiplication in frequency is convolution in time. For discrete signals, this can be performed with the fft command in Matlab on the filter coefficients h ( n ) and input signal x ( n ), then the ifft command on their frequency domain product:

Time

Domain

Frequency

Domain

X

ˆ y ( n )

x ( n ) * h ( n )

N n

1

0 x ( n ) W

N kn

m

0 x ( m ) h ( n

m )

N n

1

0 h ( n ) W

N kn

Y

ˆ

( k )

X

ˆ

( k ) ( k )

Time

Domain y

1

N

N k

1

0

Y

ˆ

( k ) W

N

nk

Linear Convolution Example

Filter Impulse Response 128 Points

Linear convolution implemented in the time domain.

Note the convolved signal length is greater than either of the originals.

Why?

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

-0.1

2

0

-2

-4

0.5

0

-0.5

-1

-1.5

20

20 40 60 80 100 120

Linear Convolution in Time Domain 148 Points

20

40

40

60 80

Signal 128 Points

100

60 80 100

120

120

140

140

140

Circular Convolution Example

Filter Impulse Response 128 Points

Convolution implemented in the frequency domain.

Note the convolved signal length is the same as the originals.

Why?

Why is there an apparent artifact at the beginning of the signal?

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

-0.1

2

0

-2

20 40 60 80

Signal 128 Points

100 120 140

-0.5

-1

-1.5

-4

20 40 60 80 100 120 140

Circular Convolution Implemented in Frequency Domain 128 Points

0.5

0

20 40 60 80 100 120 140

Circular Convolution Example

Filter Impulse Response 256 Points by Zero Padding

Convolution implemented in the frequency domain with zero padding.

Why is the apparent artifact from the nonzero pad example no longer present?

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

-0.1

2

0

-2

50 100 150

Signal 256 Points by Zero Padding

200 250

-4

50 100 150 200 250

Circular Convolution Implemented in Frequency Domain 256 Points

0.5

0

-0.5

-1

-1.5

50 100 150 200 250

Homework(2)

Use the FFT to filter a 32 point square pulse s [ n ]: s [ n ]

1 for 29

0 elsewhere n

16

(index n starts a 0) where the FIR filter has impulse response h [ n ]: h [ n ]

n for

0 for

12

32

n n

0

12 a) Use the fft command to take signals into frequency domain without padding with zeros. Take inverse fft to obtain time domain signal. Plot the filtered signals and explain what you observe.

b) Use the fft command and pad with zeros to double the signal lengths and repeat part (a)

FFT for Signal Analysis

The FFT can be applied directly to finite duration energy signals to examine the spectral content of the signal.

For Matlab’s FFT:

FFT(X) is the discrete Fourier transform (DFT) of vector X. For matrices, the FFT operation is applied to each column.

FFT(X,N) is the N-point FFT, padded with zeros if X has less than N points and truncated if it has more.

FFT of a Rayleigh Ring

Write a Matlab script to Generate a tone modulated by a Rayleigh envelope. Plot the signal, its spectra, and play the sound.

% Simulate a Rayleigh envelope ring, truncate it, take its FFT and examine

% its spectral content fr = 250; % Frequency of the ring sigma = .05; % effective duration TIMES 2 of ring fs = 8000; % Sampling frequency dur = .25; % signal duration in seconds nfft = 4096; t = [0:round(dur*fs)-1]/fs; % Create time axis ring = (t/sigma).*exp((-t.^2)/(sigma^2)).*sin(2*pi*t*fr); % Generate Ring signal figure(1) plot(t, ring) % Plot ring title('Rayleigh Envelope Ring Signal') xlabel('Seconds') ylabel('Amplitude') soundsc(ring,fs) % Play sound

FFT of a Rayleigh Ring

spec0 = fft(ring); % No Zero pad spec1 = fft(ring,nfft); % Zero pad (or truncate) to NFFT points spec2 = fft(ring,2*nfft); % Zero pad to 2*NFFT

% Create frequency axes for each of the spectra faxis0 = fs*[0:length(spec0)-1]/length(spec0); faxis1 = fs*[0:length(spec1)-1]/length(spec1); faxis2 = fs*[0:length(spec2)-1]/length(spec2);

% Plot spectrum with zero padded version on the same graph and compare figure(2) % Magnitude plot(faxis0, abs(spec0),'k',faxis1, abs(spec1),'r--',faxis2, abs(spec2),'g.') legend([int2str(length(t)) ' point FFT'], [int2str(nfft) ' point FFT'], [int2str(2*nfft) ' point FFT']) title('Magnitude ffts with zero padding') xlabel('Hertz') ylabel('Magnitude') figure(3) % Phase plot(faxis0, 180*phase(spec0)/pi,'k',faxis1, 180*phase(spec1)/pi,'r--',faxis2, 180*phase(spec2)/pi,'g.') legend([int2str(length(t)) ' point FFT'], [int2str(nfft) ' point FFT'], [int2str(2*nfft) ' point FFT']) title('Phase ffts with zero padding') xlabel('Hertz') ylabel('Degrees')

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

-0.1

-0.2

-0.3

-0.4

-0.5

0

FFT of a Rayleigh Ring

ffts with zero padding

(Zero Padding Effects)

Rayleigh Envelope Ring Signal

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

100

90

80

210 220 230 240 250 260 270 280 290

Hertz

Phase ffts with zero padding

2000 point FFT

4096 point FFT

8192 point FFT

50

2000 point FFT

4096 point FFT

8192 point FFT

0

0.05

0.1

Seconds

0.15

0.2

0.25

-50

-100

-150

-200

-250

200 210 220 230 240 250 260 270 280 290 300

Hertz

Homework(3)

Create a signal consisting of 2 sine waves with amplitude 1 and sampled at 4000 Hz. Set one with frequency 250 Hz and the other with 254 Hz. a) Take the DFT using window length of 0.05, 0.25 and

0.5 seconds. Describe what you see and make generalizations about the impact of signal length on frequency resolution.

b) Repeat part (a) using zeros padding so that each signal length is effectively 1 seconds. Describe what you see and make generalization about the impact zero padding on frequency resolution.

FFT of Extended Non-Stationary Signals

When the signal is long with changing dynamics, as would be the case for a speech or music signal, the FFT must be applied to short segments of these signals.

To reduce truncation effects, a tapering is used to bring the ends of the segment close to zero a the points of truncation.

To ensure that information is not lost in the truncation and tapering, an overlap between signal segments is used.

Impact of Windowing

1.5

Hamming Window 1

1 The windowed DFT is the product of the original signal and the windowing function: x w

[ n ; m ]

x [ n ] g [ n

m ]

0.5

0

-0.5

-1

-1.5

0 where x [ n ] is a signal of infinite extend, n is the sample index, g [ n ] is a finite widow.

3

2

1

100

Hamming Window 2

200

Samples

300 400

0

-1

-2

-3

0 100 200 samples

300 400

500

500

0.3

0.25

0.2

0.15

0.1

0.05

0

Impact of Windowing

4

In the frequency domain this becomes convolution with the window DFT:

2

0

-2

X

ˆ w

[ k ; m ]

l

N

1

0

X

ˆ

[ l ]

ˆ

[ k

l ] exp( j 2

km )

0

-2

-4

0

4

2

-4

0

100

100 200

Hamming window

200 samples

300

Boxcar window

300

400

400

0.02

Boxcar window

Not windowed (very long segment)

Hamming window

0.04

0.06

0.08

0.1

0.35

0.3

0.25

0.2

0.15

0.1

0.05

0

0

Hamming window

Boxcar window

Not windowed (very long segment)

0.1

0.2

Hertz

0.3

0.4

500

500

0.5

Hertz

Spectrogram for Signal Analysis

For a signal that deterministically changes spectral properties over time, the DFT over local time windows must be computed and indexed. This function is referred to as the spectrogram:

N

1

X

ˆ

N

[ k ; m ]

n

0 x [ n

mT ] g [ n ] W nk

N where m is the time index, T is the sample increment to the next window position, which effectively slides the N point analysis window over consecutive (often overlapping) segments of the signal x [ n ]. The

DFTs are plotted along the y-axis, while the x-axis is time (usually corresponding to the short-time window centers. The result is a function that shows how the spectrum changes over time.

The following parameters must be set properly for a usable analysis: window length N, window type, window increment (overlap between consecutive windows), number of FFT points.

Spectrogram for Signal Analysis

The Matlab spectrogram command is appropriate for analyzing long deterministic or non-stationary signals.

For Matlab’s SPECTROGRAM:

>> S = SPECTROGRAM(X,WINDOW,NOVERLAP,NFFT,Fs) calculates the spectrogram for the signal sampled at Fs in vector X .

SPECTROGRAM splits the signal into overlapping segments, windows each with the WINDOW vector and forms the columns of S with their zero-padded, length NFFT discrete Fourier transforms.

Thus each column of S contains an estimate of the short-term, timelocalized frequency content of the signal X (positive frequencies only).

Time increases linearly across the columns of S , from left to right.

Spectrogram for Signal Analysis

If plotting, it is convenient to use the optional output arguments:

[S,F,T] = SPECTROGRAM(A, WINDOW, NOVERLAP, NFFT, Fs) returns a column of frequencies F for each time in T at which the spectrum was computed. F has length equal to the number of rows of

S , and T has length equal to the number of columns. If you leave Fs unspecified, SPECTROGRAM assumes a default of 2 Hz. Optional output parameters F and T are the frequency and time axes useful for plotting the spectrum:

>> imagesc(T, F, abs(S))

Spectrogram of Frequency Sweep

Write a Matlab script to Generate a frequency sweep from

20 Hz to 1.9 kHz, where Fs is 4 kHz. Then plot the magnitude of the spectrogram and play the sound.

% Simulate a frequency sweep signal and take its spectrogram and examine

% its spectral content over time

% Signal Parameters flow = 20; % Starting frequency of sweep in Hertz fend = 1900; % Ending frequency of sweep in Hertz dt = 4; % Time duration of sweep in seconds fs = 4000; % Sampling frequency

% Spectrogram Parameters wlen = 128; % Length of actual point extracted from signal segment nfft = 1024; % number of FFT point (zero padding) olap = floor(wlen/2); % Points of overlap between segments wn = hamming(wlen); % Create tapering window (also try boxcar - square window)

Spectrogram of Frequency Sweep

% Generate signal t = [0:round(dt*fs)-1]/fs; % Create time axis fsw = flow + ((fend-flow)/2)*[0:length(t)-1]/length(t); % Create Frequency ramp - Why divid by 2?

swp = sin(2*pi*t.*fsw); % Generate sweep signal soundsc(swp,fs) % Play sound

% Create Spectrogram

[b,faxis,taxis] = spectrogram(swp,wn,oplap,nfft,fs);

% Plot over time and frequency figure(1); imagesc(taxis, faxis, abs(b)) % Plot spectrogram axis('xy') % Flip y axis to put zero Hz on bottom colorbar % Include colorbar to determine color coded magnitudes on graph title(['Frequency Sweep from ' num2str(flow) ' Hz to ' num2str(fend) ' Hz']); xlabel('Seconds'); ylabel('Hz')

% Just plot at a single time instant figure(2); tindex = find(taxis >= dt/2); %Find index of halfway point over the time axis tindex = tindex(1); plot(faxis,abs(b(:,tindex))) title(['Single column from Spectrogram at ' num2str(taxis(tindex)) ' seconds']); xlabel('Hz'); ylabel('Magnitude')

Spectrogram of Frequency Sweep

Frequency Sweep from 20 Hz to 1900 Hz

2000

1800

1600

1400

1200

1000

800

600

400

200

0

0 0.5

1 1.5

2

Seconds

2.5

3 3.5

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

Single column from Spectrogram at 2 seconds

25

20

35

30

15

10

5

0

0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200 1400 1600 1800 2000

Hz

Homework(4)

Use the scale program created in a previous homework problem to generate a scale for 2 octaves starting at 256 Hz with tones of amplitude 1 and duration 0.25 seconds. Use a sampling rate of 4kHz.

A) Compute and plot the spectrogram magnitude in dB , labeling all axes correctly. Use the parameters you think best for estimating the spectrogram for this signal. Comment on the frequencies of the tones generated with your program and those identified through the spectrogram.

B) Quadruple the number of FFT points from that used in (A). Compute and plot the spectrogram, and explain difference observe from part

(A).

C) Increase the window length by a factor of 4 and set the number of FFT points to twice the amount of the window length. Compute and plot the spectrogram, and explain the observed changes.

Random Signal Analysis

If a process is changing over time, while the statistics of the process do not change over time, the process is referred to as a stationary process. In this case averaging and moment computations result in useful characterization.

If the signal’s (or process’) probability density function never changes over time, then it is referred to as strictsense stationary (SSS), if the first and second moments remain constant over time, the process is referred to as wide-sense stationary (WSS).

Power Spectral Density

The Power Spectral Density (PSD) is the average power in a signal as a function of frequency. This can be estimated by averaging DFT magnitudes squared over segments of signals from the same noise process.

P ( f )

E

S ( f )

2

1

N n

N

1

S

ˆ i

( f )

2 where E[] is the expected value, S ( f ) is the data spectrum plus noise (i.e. modeled as a random variable) and is the DFT or short-time FT estimated from independent

PSD Example Colored Noise

A popular approach to spectral estimation is to is to window a long segment of data into a sequences of shorter windows (similar to the spectrogram) and average all the

FFT magnitudes together. This is referred to as Welch's or the hopping window method. The Matlab command pwelch() implements this method.

Example: Filter white noise through a band-pass filter and compute the PSD. Compare PSD to the transfer function magnitude of the filter. Assume a sampling rate of 8kHz and a 6 th order Butterworth filter with passband from 500 to 1500 kHz.

PSD Example Colored Noise

fs = 8000; % Sampling Frequency dur = 20; % Sound duration in seconds ord = 6; plen = 32; % PSD segment length

% Bandlimit on the filter f1 = [500]; % lower bandlimit f2 = [1500]; % corresponding upper bandlimit

% colors for the plots col = ['g', 'r', 'b', 'k', 'c', 'b']; no = randn(1,round(fs*dur)); % Generate noise signal

[b,a] = butter(ord,2*[f1 f2]/fs); % Generate filter

% perform filter operation to get colored noise cno = filter(b,a,no);

% Compute PSD of noise

[p, fax] = pwelch(cno,hamming(plen),fix(plen/2),2*plen, fs); figure(1); lh = plot(fax,abs(fs*p/2),col(1)) % Plot PSD set(lh,'LineWidth',2) % Make line thicker hold on

% Find filter transfer function

[h,fq] = freqz(b,a,2*plen,fs); plot(fq,abs(h).^2,col(2)) hold off

% Label figure xlabel('Hertz', 'Fontsize', 14); ylabel('PSD', 'Fontsize', 14)

1.4

1.2

1

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

0

1.4

1.2

1

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

0

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

0

1.4

1.2

1

0.8

Window Length = 32

Spectral Estimate

Filter Magnitude Response

500 1000 1500 2000

Hertz

2500

Window Length = 128

3000 3500 4000

Spectral Estimate

Filter Magnitude Response

500 1000 1500 2000

Hertz

2500

Window Length 512

3000 3500 4000

Spectral Estimate

Filter Magnitude Response

500 1000 1500 2000

Hertz

2500 3000 3500 4000

Autocorrelation Function

As a measure of how quickly a signal changes on average, or for the detection of periodicities, the autocorrelation can be used. It directly measures the correlation between samples separate in time by a particular interval or lag .

Define the autocorrelation of a sequence as: r ( k )

N n

1

0 x ( n

k ) x ( n ) where x ( n )

0 for n

0 and n and

N

k

N

N1

Autocorrelation Example

Repeat previous example for signal generation and compute the autocorrelation function. Show autocorrelation for white noise (filter input) and colored noise (filter output).

% Compute auto correlation of input sequence mxlag = fs*.02; % Only compute lags up to .1 seconds

[acwno, lagwno] = xcorr(no, mxlag, 'coef');

% Plot lags figure(2); plot(1000*lagwno/(fs),acwno) xlabel('milliseconds','Fontsize', 14); ylabel('Correlation coefficient','Fontsize', 14)

% Compute auto correlation of output sequence mxlag = fs*.02; % Only compute lags up to .1 seconds

[accno, lagcno] = xcorr(cno, mxlag, 'coef');

% Plot lags figure(3); plot(1000*lagcno/(fs),accno) xlabel('milliseconds','Fontsize', 14); ylabel('Correlation coefficient','Fontsize', 14)

Autocorrelation Example

Repeat previous example for signal generation and compute the autocorrelation function. Show autocorrelation for white noise (filter input) and colored noise (filter output).

White noise AC

1.2

1

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

-0.2

-20 -15 -10 -5 0 milliseconds

5 10 15 20

Colored noise AC

1

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

-0.2

-0.4

-0.6

-0.8

-20 -15 -10 -5 0 milliseconds

5 10 15 20

Autocorrelation and PSD

The AC and PSD are DFT pairs. The DFT of the AC is shown below:

Colored noise AC

1

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

-0.2

-0.4

-0.6

-0.8

-20 -15 -10 -5 0 milliseconds

5 10 15 20

DFT of AC

3

2.5

2

1.5

1

0.5

0

0

4.5

4

3.5

500 1000 1500 2000

Hertz

2500 3000 3500 4000

Homework(5)

Generate 3 seconds of white noise at a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz. Use the following coefficients in an IIR filter to filter the white noise and generate pink noise ( bnum are numerator and aden are denominator coefficients).

bnum = [ 0.04957526213389, -0.06305581334498, 0.01483220320740 ] aden = [ 1.00000000000000, -1.80116083982126, 0.80257737639225]

Coefficients from http://music.columbia.edu/pipermail/music-dsp/2001-November/046099.html

A) Estimate the AC and PSD of the Pink noise and present their plots.

Comment on the observed differences from white noise.

B) Add a sinusoid of frequency 220 Hz to the pink noise signal with power equal to that of the pink noise (i.e. p = std(pink noise signal) and sig = sqrt(2)*p*sin()) repeat part (A). Show the plots and explain the differences observed with the plots from part (A). Does this make sense since the sine function is not random?

Homework (6)

a) Create a tone at 450 Hz with sampling rate 8000, amplitude

0.707, and duration 3 seconds. Add white noise (use the randn function) with a signal-to-noise ratio of 12 dB. Use the fir1 command to design a 30 and 120 th order band-pass filter from 400 Hz to 506 Hz. Plot the magnitude response of the filters. Use filter to filter the signal and listen to the sound before and after filtering. Plot the signal spectral magnitudes before and after filtering (use the fft function).

Describe the differences you hear between the signals for before and after filtering and compare the before and after filtering spectra.

b) Repeat part (a) comparing a 5 th order elliptical filter with passband ripple of .5 dB and stopband ripple of 30 dB and a

5 th order Butterworth filter.

Homework(7)

Use Sinc function interpolation to upsample by a factor of

50 the band-limited signal is given in terms of its samples below. Assume signal is bandlimited to 0.5 Hz. The sampling rate ( B ) is 1 Hz.

F = [0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0]

Note: a) Matlab has a sinc function (see help sinc) b) A step edge is not bandlimited so the interpolated bandlimited function will have overshoot and undershoot between the given samples (i.e. it will not look like a sharper step).

![Y = fft(X,[],dim)](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005622160_1-94f855ed1d4c2b37a06b2fec2180cc58-300x300.png)