Habits of Mind

Habits of Mind …

Another perspective on curriculum design

Habits of Mind…

knowing how to behave intelligently when you

DON'T know the answer.

having a disposition toward behaving intelligently when confronted with problems, the answers to which are not immediately known: dichotomies, dilemmas, enigmas and uncertainties.

Arthur Costa and Bena Kallick, Habits of Mind, A Developmental Series

Habits of Mind…

Performative Literacy – knowledge that enables readers to activate and use all the other forms of knowledge required for the exercise of anything like a critical or disciplined literacy

Sheridan Blau, Performative Literacy: The Habits of Highly Literate Readers

Habits of Mind…

… ways of thinking that one acquires so well, makes so natural, and incorporates so fully into one’s repertoire, that they become mental habits – not only can one draw upon them easily, one is likely to do so.

E. Paul Goldenberg, “ Habits of Mind” as an Organizer for the Curriculum

Another perspective

New term for old concepts

Intelligence can be taught (Whimbey, 1975)

Multiple Intelligences (Gardner, 1983)

Learnable Intelligence (Perkins, 1995)

Emotional Intelligence (Goleman, 1995)

Moral Intelligence (Coles, 1997)

(Costa and Kallick)

So why teach habits …?

People know how to think better about something, but are not disposed to do so …

“Without inclination, a person will not feel drawn toward X behavior. Without sensitivity, a person will not detect an X occasion.”

Perkins, Jay, and Tishman, Beyond Abilities: A Dispositional Theory of Thinking

So why teach habits …?

Habits of mind …

emphasize attitudes, habits, and character traits in addition to cognitive skills; accommodate roles that emotions play in good learning; encourage intellectual “sensitivity” – recognizing opportunities to engage in intellectual behavior; support thought across and beyond disciplines.

(Costa and Kallick)

So why teach habits …?

A curriculum organized around habits of mind …

builds a background for advanced study in the discipline gives a strong sense of how practice in the discipline is actually done serves the needs of students preparing for advanced study as well as students who have not developed skills or interest in the discipline

(Goldenberg)

So why teach habits …?

Finally, talking about habits of mind …

provides a common talking point for instructors across disciplines and grade levels allows course designers to choose those habits of mind that best serve most students general education purposes.

(Goldenberg)

Costa & Bennick’s habits

4.

5.

6.

1.

2.

3.

7.

8.

9.

Persisting

Managing impulsivity

Listening to others

Thinking Flexibly

Thinking about thinking

Striving for accuracy and precision

Questioning

Applying past knowledge to new situations

Thinking and communicating with accuracy and precision

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

Gathering data through all senses

Creating, imagining, and innovating

Responding with wonder and awe

Taking responsible risks

Finding humor

Thinking interdependently

Learning Continuously

Thinking dispositions

5.

6.

7.

3.

4.

1.

2.

To be broad and adventurous

Toward sustained intellectual curiosity

To clarify and seek understanding

To be planful and strategic

To be intellectually careful

To seek and evaluate reasons

To be metacognitive

(Perkins, Jay, and Tishman)

Habits of critical thinkers

3.

4.

5.

6.

1.

2.

Respect for reasons and truth

Respect for highquality products and performances

Inquiring attitude

Open-mindedness

Fair-mindedness

Independentmindedness

7.

8.

9.

Respect for others in group inquiry and deliberation

Respect for legitimate intellectual authority

Intellectual work ethic

Bailins, Case, Coombs, and Daniels, Conceptualizing Critical Thinking

Blau’s performative literacy

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

1.

2.

Sustained focused attention

Willingness to suspend closure – to entertain problems rather than avoid them

Willingness to take risks

Tolerance for failure – willingness to re-read and re-read again

Tolerance for ambiguity, paradox, and uncertainty

Intellectual generosity and fallibility

Capacity to monitor and direct one’s own reading process – metacognitive awareness

From the CES

Ted Sizer proposes:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

Perspective

Analysis

Imagination

Empathy

Communication

Commitment

Humility

Joy

CPESS habits of mind:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Evidence – how do we know what we know?

Perspective – who says?

Connection – what causes what?

Supposition – what if?

Relevance – who cares?

Habits of Mind . CESNationalweb. http://www.essentialschools.org

From BYU – 1

st

Year Exp.

4.

5.

6.

1.

2.

3.

Curiosity

Questioning

Observation (through paying attention)

Analysis (understanding the parts)

Integration (understanding the whole)

Persistence

Habits of Mind. Office of First-year Experience, Brigham Young University

Science habits of mind

1.

2.

3.

4.

Curiosity

Openness

Skepticism

* Balance between the two a central tension in all science. Too skeptical results in no new ideas tested.

Too open results in no commitment to existing ideas.

Communication

Willingness to discuss and debate, share, cooperate and collaborate.

Mark Volkmann and David Eichinger, Habits of Mind: Integrating the Social and Personal Characteristics of Doing Science into the Science

Classroom.

Mathematics habits of mind

Students should be …

Cuocco, Goldenberg, and Mark.

Habits of Mind: an Organizing Principle for Mathematics Curricula

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

Pattern sniffers

Experimenters

Describers

Tinkerers

Inventors

Visualizers

Conjecturers

Guessers

Social Studies habits of mind

3.

4.

5.

1.

2.

6.

Open mindedness

Fair-mindedness

Independent-mindedness

Inquiring or “critical” attitude

Respect for high quality products and performances

Intellectual work ethic

Roland Case and Ian Wright, Taking Seriously the Teaching of Critical Thinking

Habits in the curriculum …

What we are proposing is something a bit different. It is not an act of faith that taking mathematics seriously gives one the mathematics directly and

(also) improves one’s thinking, but almost the reverse: taking particular ways of thinking seriously and giving them top priority among the various principles one needs for organizing mathematics (or other) curricula, gives one the thinking skills directly and also improves one’s mathematics.

(Goldenberg)

Habits in the curriculum …

Habits in the curriculum …

In considering habits, Goldenberg proposes …

1)

What “habits of mind” do people need to be safe, healthy, employable, socially connected ...? What

“habits” will they need to be adaptive to unforeseen obstacles and new problems

2) a.

b.

What special contributions to that thinking can my discipline make?

What knowledge and skills from my discipline best help to deliver the message about thinking?

What might best convey the flavor of my discipline?

c.

What might be the most broadly useful to students?

Habits in the curriculum …

Habit is a cable; we weave a thread of it each day, and at last we cannot break it.

Horace Mann

Habits in the curriculum …

Habit:

A recurrent, often unconscious pattern of behavior that is acquired through frequent repetition.

An established disposition of the mind or character.

Habituate:

To accustom by frequent repetition or prolonged exposure

The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language

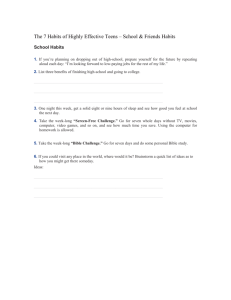

Habits in the curriculum …

A habits of mind approach requires:

Multiple opportunities for practice, becoming increasingly varied and complex and in different contexts over time.

“Thinking Occasions”

(Barry Beyer, Improving Student Learning )

Providing Scaffolds

Modeling

Opportunity for reflection and “self-talk”

Thinking Occasions

Beyer, quoting Vygotsky, notes that –

Thinking occasions are not “time to think” add-ons.

Rather, they are occasions that demand thinking.

These occasions actually provoke thinking, by triggering it and calling it into play.

Scaffolds …

A Support for thinking

Strategies/Mental Models

Worksheets/ graphic organizers

Modeling open-ended nature of research

Modeling …

At some point in our lives, each part of the intellectual process demanded our full concentration. But once learned

(or, more precisely, once mastered), our mental habits became so automatic that they faded from view.

It is that very point that spells trouble in the classroom. For the same aspects of cognition that ease our job as thinkers pose the greatest threat to our effectiveness as teachers.

Our familiar mental habits, often overlooked or omitted when we describe our thinking processes to others, can create a gulf between us and our students.

Sam Wineburg, Teaching the Mind Good Habits

Professors may assume that their students are stupid or suffer from a learning disability. Often the truth is much simpler: No one has ever bothered to teach them some basic but powerful skills of interpretation.

As teachers, we need to remember what the world looked like before we learned our discipline's ways of seeing it. We need to show our students the patient and painstaking processes by which we achieved expertise. Only by making our footsteps visible can we expect students to follow in them.

Wineburg