LAWS13010 Evidence and Proof - Carpe Diem

advertisement

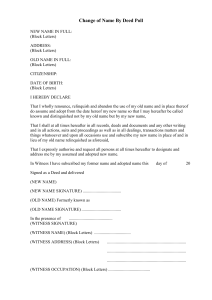

LAWS13010 Evidence and Proof Topic 6 – Documentary and Real Evidence Learning Objectives At the end of this topic, you should be able to: • Describe the major forms of documentary evidence; • Describe the relationship between documentary evidence and hearsay evidence; • Outline the statutory rules for the use of documents in Qld; • Identify the importance of authenticating documents, and how this may be accomplished; • Outline the circumstances in which exhibits may be used; • Discuss the nature of courtroom demonstrations, and whether they are useful or mere drama; and • Outline the process of a view, and the limitations on what may be learned during a view. What is a document? A document, in its modern context, is any medium upon which information may be stored and then later retrieved by someone with the appropriate equipment. Documents are usually important for the information which they may therefore convey to the courts. The range of categories of document are not closed. As new technologies develop, and new means of information storage and retrieval are developed, these means will fall into the definition of “document.” Note there are two relevant statutory definitions in Queensland. Evidence Act 1977, Sch 3 Acts Interpretation Act 1954, s.36 Documents are Hearsay Hearsay is evidence of a representation made outside the courtroom itself. (We will learn more about hearsay in coming weeks) The data contained within a document is, by its very nature, a representation made outside the courtroom. The question may always be asked: Why cannot the maker of the original document come to court to give evidence? Documents: Pros and Cons + Documents can be expressed with much greater precision than oral evidence, providing the court with more considered views; - There is no reason why a person providing documentary evidence should have the advantage of being able to weigh and consider their words; + Document can be made at, or close to the time of an incident, and they do not degrade with time; - Documents are not amenable to cross-examination; you can cross-examine the maker of the documents, but again, why not just have them give oral evidence? Common Law Rules 1. Documents, to be used, had to fall under one of the “hearsay exceptions” 2. The original document was generally required to be tendered. Butera v DPP 3. Even once admitted, the document might not be used for all purposes – its purposes were limited to the extent of the hearsay exception. 4. The document must be authenticated, either by being “adopted” by a person, or by being identifiably traceable to a machine which created the document. Statutory Rules – Civil Cases Section 92(1) Evidence Act 1977 (Qld) Permits the admission into evidence in CIVIL proceedings two types of documentary hearsay: • 92(1)(a): statements that contain “first-hand” hearsay, that is, statements where the maker had personal knowledge of the contents • 92(1)(b): statements that were recorded or compiled “in the course of” an “undertaking”, based on information supplied by a person who had personal knowledge of what was being recorded. Note: • Not mutually exclusive provisions • Must be evidence that would be admissible were it to be given in oral form (eg, not an inadmissible opinion) • Information must be in the personal knowledge of the maker of the statement or supplier of the information • Undertaking is a very wide concept • Eg, Kenny v Nominal Defendant [2007] QCA 185 Statutory Rules – Civil Cases • Section 92(1) contains the requirement that the maker of the statement in the document be called as a witness • Section 92(2) provides really useful exceptions to the need to call the witness in order to have the document that falls within a s 92(1) category admitted into evidence Statutory Rules – Civil Cases • 92(2) contains 6 exceptions to the need to call the witness, while still allowing the document to be admissible: • Witness is dead, or physically or mentally unfit • Witness is out of the state and it is not reasonably practicable to secure their attendance • Witness cannot with reasonable diligence be found/ID’d • Witness unlikely to have a personal recollection • Consent, ie, no party wants to cross examine the witness • Court believes it would involve undue delay or expense Statutory Rules – Criminal cases • s93(1) is narrower than s92 • CRIMINAL cases only • It exists to permit the admission of appropriate trade or business documents only • Applies to “trade or business” documents, narrower than the documents of an “undertaking” • Must be otherwise admissible information • Standard of proof on a voir dire of this kind is on the balance of probabilities Statutory Rules – Criminal cases • 93(1)(b) exceptions: • Witness is dead, or physically or mentally unfit • Witness is out of the state and it is not reasonably practicable to secure their attendance • Witness cannot with reasonable diligence be found/ID’d • Witness unlikely to have a personal recollection Statutory Rules – s93A • Relates to children and witnesses with ‘an impairment of the mind’ • A special regime for admitting, as evidence of the truth of their contents, statements made out of court by persons u/16, 16-17 who are ‘special witnesses’ or persons with an impairment of the mind • It’s a statutory exception to the hearsay rule Statutory Rules – s93A • 4 basic conditions before a statement will be admissible under s 93A: • The maker of the statement was, at the time of making it, a child, or a person with ‘an impairment of the mind’ • The maker of the statement had personal knowledge of its contents • The child or intellectually impaired person is available to give evidence in the proceeding • The statement in question is “in a document” • This is how the video-recorded evidence these witnesses is tendered, works with s21A Statutory Rules – s93A • 93A(3) entitles the person against whom the statement is admitted (usually the defendant) to insist that the Crown call the witness for XXN as well as the person who recorded it • The 93A statement constitutes their EIC • Witness may still get s21A facilities for XXN • 93A(2A): related statement provisions • • Practical necessity: the questions asked by an interviewer in recorded evidence are admissible because the witness’ evidence would be meaningless without it A 93A statement is not an exhibit at trial, but a record of the testimony it contains: Gately v The Queen (2007) 232 CLR 208 Statutory Rules • 93B applies for “dying declaration” situations. If A said something to B but A is now dead or mentally or physically incapable of giving evidence, hearsay evidence of a representation made to B about an asserted fact about which A had personal knowledge is admissible • Only in cases of homicide, suicide, concealment of birth, offences endangering life and health, assaults, rape, sexual assaults • R v Lester (2007) 176 A Crim R 152: a statement made by a person now deceased as to their state of mind at the time they made the statement might, if relevant, be admitted as ‘an asserted fact’. Estranged wife of the accused said she was in fear of her husband, she had been told he had hired someone to kill her. He was on trial for hiring a hit man to kill her. Admissible for her state of mind at the time she said it, not for proof that he actually hired a hit man. Statutory Rules • 93C allows either party to request that the trial judge warn the jury of the potential unreliability of hearsay evidence, where it is admitted under s93B. Judge must comply unless there is good reason not to do so. Statutory Rules • Section 95 deals with the admission into evidence, as proof of the facts contained therein, of what are described as statements “contained in a document produced by a computer” • It is a form of exception to the hearsay rule • Allows the evidence to be admitted provided that someone can vouch for the reliability of the computer and the system under which it was employed • Applies in civil and criminal proceedings • Compare admissibility of “books of account” under s84 Statutory Rules • S95(2) contains the conditions under which computer generated hearsay evidence will be admissible: • The document was produced by the computer during a period in which the computer was used regularly to store and process information in connection with the activities of the person employing it • Information of the kind contained in the statement, or of the kind from which the information was derived, was regularly supplied to the computer over that same period • Throughout the material part of that period the computer was operating properly, or if it was not, any malfunction did not affect the production of the document or the accuracy of its contents • The information contained in the statement reproduces, or is derived from, information supplied to the computer in the ordinary course of its activities Computer generated documents Most computer documents are admissible on the same terms as any other document. A certificate is required in order to authenticate the document. Evidence Act 1977 (Qld) s.95 See, eg, Carloan v Cohen (2011) QDC 103 However, two types of computer evidence are not regarded as hearsay: 1. Where the computer is used as a calculating device, provided the calculation method can be verified; 2. Where the computer records data not generated by a human being. DNA DNA evidence in criminal proceedings operates under different rules from any other form of documentary evidence. The CEO of the Health Department may appoint analysts to be DNA Analysts under EA s.133A. A certificate from such an analyst is evidence of its contents. However if a party seeks to rely on the certificate, the analyst must be made available to give evidence. Evidence Act 1977 (Qld) s.95A Statutory Rules • S94 provides that where a statement is admitted under s 92, 93 or 93A and the person who supplied the information is not called as a witness, any evidence that would have been admissible for either supporting or destroying their credibility as a witness will be admissible, along with any previous inconsistent statements or previous convictions of the witness affecting their credibility • S98 allows the court to reject in its discretion any statement or representation if for any reason it appears to be inexpedient in the interests of justice for it to be admitted • S99 allows to court to direct that a document not be allowed to be taken by the jury into the jury room if it appears that the jury might, if it was taken in, give it undue weight Business Records Most business records will be treated the same as any other forms of documentary evidence; i.e. they will be admitted or excluded under EA s.92 or 93. Different rules exist for “Books of Account,” i.e. accounting records. Sections 83 and 84 EA deal with these. Applies in civil and criminal matters. Books of account are regarded as evidence automatically, without any need to call the maker of the documents to give evidence. (Evidence Act 1977 (Qld) Pt 5, Div 6.) Photographs Photographs, whether taken by a machine or by a person, can be admitted into evidence on the same terms as any other document. Authentication by the photographer (where one exists) will normally be necessary (if veracity is contested). Case law exists to suggest that the “negatives” should not have been “retouched”. Is photography less reliable in the Photoshop era? Photography and shock value Graphic injuries Child pornography Audio recordings The playing of an audio recording in court is evidence of the content of the recordings. Butera v DPP If the audio is available, a transcript is not sufficient. Note, however, that in the Uniform Evidence Act jurisdictions, a transcript may be used. Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) s.48(1)(c) What about covert taping? Consider that evidence may not be admissible if it was collected illegally or if its use would be unfair to the defendant (in a criminal matter). Real Evidence The defining characteristic of real evidence is that it is seen or experienced by the court directly, as opposed to documents or testimony which tell the court about things that happened outside the court. Real evidence does not, however, speak for itself. Real evidence must be authenticated by testimony. If that is the case, of what use is real evidence? Can real evidence offer perspective and context which cannot be offered by testimony? Or is its true value that it may be more exciting, particularly to jurors? The Witness in the Courtroom Judges and juries will inevitably obtain three types of information from witnesses: 1. Information directly from testimony; 2. Information as to credibility: Was the witness evasive? Was the witness lying? Was the witness unreasonably uncomfortable? 3. Information arising from human experience: Did the witness have strong command of English? Did the witness have a physical diability? Is the witness of normal intelligence? Recall GIO v Bailey When is a document real evidence? Sometimes the line between an item of real evidence and a document are indistinct. If a computer, or a USB memory stick, or an audio CD are stolen and then later produced in court, are they an exhibit or are they a document? Or a heavy book or hard drive that was used to assault someone with a blow to the head? How about a T-shirt with an offensive slogan? The key question is whether the item is relevant in itself (real evidence), or whether the item is relevant because of the information that can be retrieved from it (document). Courtroom demonstrations Courtroom demonstrations are almost inherently unreliable except as ancillary demonstrations to support oral testimony. For instance, normal body language might constitute a demonstration, or a witness might be asked to demonstrate a gesture or an action which they say they conducted. An attempt at a re-enactment is unreliable due to the difficulty of faithfully reproducing the circumstances of the alleged offence. R v Alexander – Robbery at a newsagent – surrounding lighting etc may have changed. Li Shu-Ling v The Queen – Murder re-enacted on video – no way of being sure the re-enactment was faithful. What if both sides produced reenactments? Would they be different? Views A “view” occurs when the court travels outside the courtroom, in order to see something which cannot be brought into court. Views must be handled with great care: … a view is for the purpose of enabling the tribunal to understand the questions that are being raised, to follow the evidence and to apply it, but not to put the result of the view in place of evidence. Unstead v Unstead, quoted in Scott v Numurkah Note, however, that under the Uniform Evidence Acts, a view may be used as evidence in the same manner as an exhibit. Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) ss. 53-54. Views Plaintiff asked for the court to inspect a similar crane and its load as the one the subject of the dispute. Also asked for a demonstration of its capabilities when used in a similar manner to that alleged by plaintiff. Court allowed the view but not the demonstration. Because the way that the crane was operated was central to the dispute, it would have the unreliability of a reconstruction. Matton Developments Pty Ltd v CGU Insurance Ltd [2014] QSC 256 Review In this topic, you have learned: • The various types of formats regarded, for evidence purposes, as “documents”; • The fact that documents are inherently hearsay, and the general rules surrounding their use; • Specific rules for photographs, audio recordings, computer documents, business records, and DNA reports; • The three types of real evidence: the witness in court, exhibits, and courtroom demonstrations; and • The concept of a “view”, which is almost (but not quite) evidence. Congratulations! You are now half way through this course! See you for our tutorial next week.