Document 9237543

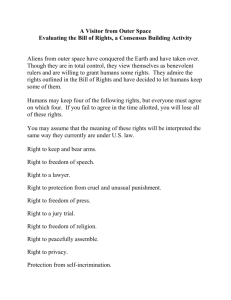

advertisement