Fall 2014 (all except Part II)

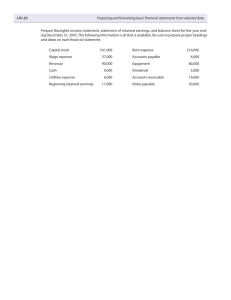

advertisement

1 Accounting for Lawyers Professor Bradford Fall 2014 Exam Answer Outline The following answer outlines are not intended to be model answers, nor are they intended to include every issue students discussed. They merely attempt to identify the major issues in each question and some of the problems or questions arising under each issue. They should provide a pretty good idea of the kinds of things I was looking for. In some cases, the result is unclear; the position taken by the answer outline is not necessarily the only justifiable conclusion. I graded each question separately. Those grades appear on your printed exam. To determine your overall average, each question was then weighted in accordance with the time allocated to that question. The following distribution will give you some idea how you did in comparison to the rest of the class: Part Part Part Part Part I, Question 1: Range 5-9; Average = I, Question 2: Range 3-9; Average = I, Question 3: Range 2-8; Average = I, Question 4: Range 4-8; Average = I, Question 5: Range 4-9; Average = Part II: Range 4-9; Average = 6.75 7.31 6.50 6.19 6.31 6.31 Total Exam Score (70% of grade): Range 5-9; Average = 6.63 Homework (30% of grade): Range 6-9; Average = 8.06 All of these grades are on the usual law school scale, with 9 being an A+ and 0 being an F. If you have any questions about the exam or your performance on the exam, feel free to contact me to talk about it. 2 Part I, Question 1 Present Value of the Settlement Offer The Annuity Component The first component of the settlement offer is an annuity. We can use Table 10-3 (p. 255 of the book) to calculate the value of this annuity. However, the table is based on annuities paid at the end of the year. The first payment of the settlement is paid immediately, at the beginning of the year, but this is equivalent to a payment now, which already is a present value, and a nine-year annuity payable at the end of each of the nine years. The present value factor for the nine-year annuity (using 9 for n and 4% as the discount rate) is 7.435. Multiplying this by the amount of the payment, we get a present value of $7,000 x 7.435 = $52,045. We then add the initial payment of $7,000 to this, $52,045 + $7,000 + $59,045. Thus the total present value of the ten payments is $62,045. The Lump-Sum Payment The second component of the settlement offer is a lump -sum payment to be paid in 15 years. The formula for its present value is PV = FV/(1 + r) n , where r is the discount rate and n is the number of years. = $50,000/(1.04) 15 = $27,763.23 [Alternatively, you could use Table 10-2 (p. 254 of the book). The present value factor for a payment in 15 years with a discount rate of 3 4% is 0.5553. Multiplying this by $50,000, we get $50,000 x .5553 = $27.765.] Adding the two components together, the total present value of the settlement offer is $59,045 + $27,763.23 = $86,808.23. Present Value of Taking the Case to Trial To determine the present value of taking the case to trial, we must calculate the present value of the judgment and subtract the present value of the payments Susan must make for fees and expenses. The judgment is a single, lump-sum payment to be made in three years. The formula for its present value is PV = FV/(1 + r) n , where r is the discount rate and n is the number of years. = $135,000/(1 + .04) 3 = $120,014.51 [Alternatively, you could use Table 10-2 (p. 254 of the book). The present value factor for a payment in 3 years with a discount rate of 4% is 0.8890. Multiplying this by $135,000, we get $135,000 x .8890 = $120,015.] The three payments for costs and attorneys’ fees are an annuity. We can use Table 10-3 (p. 255 of the book) to calculate the value of this annuity. The present value factor for the three-year annuity (using 3 for n and 4% as the discount rate) is 2.775. Multiplying this by the amount of the annuity, the present value of the annuity is -$10,000 x 2.775 = -$27,750. Adding the two annuities, the present value of taking the case to trial is $120,015 - $27,750 = $92,265. 4 Conclusion Taking the case to trial has a higher present value ($92,265) than accepting the settlement ($86,808). 5 Part I, Question 2 The cost of an asset for depreciation purposes includes not only the purchase price, but also the cost of moving it to the location and condition of its intended use. The cost of the packaging machine would therefore include the $17,500 price paid for the machine, the $600 cost to ship it to the cannery, and the $400 cost to modify it for use by Mountain. The regular oil and maintenance costs are repairs that would not be capitalized into the cost of the machine. Thus the total cost for depreciation purposes is $17,500 + $600 + $400 = $18,500. The useful life of the machine for depreciation purposes is its expected life to Mountain, not how long the machine will last. That is 5 years. The salvage value is $4,500. To apply the double-declining balance method, we use twice the straight-line rate of 20% (1/5 a year over the 5-year life) and apply that rate to the net book value of the machine each year. We don’t subtract salvage value from the depreciable cost, but we never depreciate below the salvage value. The depreciation expense for each year would be: Year 1 $18,500 x .4 = $7,400. (Net book value = $18,500 -$7,400 = $11,100) Year 2 $11,100 x .4 = $4,440. (Net book value = $11,100 – 4,440 = $6,660) Year 3 $6,660 x .4 = $2664. 6 (Net book value = $3,996) Since the salvage value is $4,500, we can only have a depreciation expense of $2,160 in Year 3, leaving a net book value of $4,500. We can’t depreciate below the salvage value, so the depreciation expense for Years 4 and 5 would be $0. 7 Part I, Question 3 Consent The firm can respond to this audit inquiry only with the consent of the client, Acme. ABA Statement of Policy Regarding Lawyers ’ Responses to Auditors’ Requests for Information, ¶ 1. The letter from Paul Prez is sufficient consent, unless we are disclosing a client confidence or evaluating a claim. Since, as discussed below, we will be evaluating a claim, we need to get informed consent from Acme. We must explain the consequences of our disclosure to Acme and provide a response only after they agree to that disclosure. The ABA Statement suggests that we share a draft of our response to the auditor, although that isn’t required. What We May Comment On All three of the items you mentioned are loss contingencies. We can discuss only those loss contingencies specified in ¶ 5 of the ABA Statement. The Smith accident falls within ¶ 5(a)—overtly threatened or pending litigation—since the plaintiff ’s lawyer is aware of the claim and the likelihood of litigation or settlement is certainly more than remote (meaning “slight” or “extremely doubtful.”) The guaranty falls within ¶ 5(b). It is a contractually assumed obligation that the client has specifically identified and requested comment on. The possible chemical spill liability falls within ¶ 5(c). It is an unasserted claim. Since the client has not specifically identified it and requested comment, ¶ 5 does not allow us to comment on it. ¶ 5 says that we should not comment in response to a general request of the sort in ¶ 3 of Prez’s letter. However, we should make clear in our response that we are limiting our comments to those matters allowed by the ABA Statement of Policy. 8 General Information We may always provide general information about the Smith and Big Bank matters: “an identification of the proceedings or matter, the stage of proceedings, the claim(s) asserted, and the position taken by the client.” ABA Statement ¶ 5. Thus, as to the Smith claim, we may say that Smith is asserting liability with respect to an auto accident that occurred in March in Bellevue, Nebraska, that he has not yet filed suit, that we deny liability, and that we are negotiating with Smith’s attorney. As to the Big Bank guaranty, we may say that we have entered into a guaranty of the loan to First State Bank and the specifics of the loan and guaranty. The question is whether we may, in either case, provide an opinion as to the probable outcome or offer an estimate of the expected loss or range of loss. The Smith Accident We may not express an opinion as to the probable outcome of the Smith case. The ABA Statement allows us to express such an opinion only when an unfavorable outcome is either probable or remote —in essence, where either Acme’s chances of winning or Smith’s chances of winning are “slight.” ABA Statement ¶ 5. Since it’s not clear who was at fault, we can’t say that either side has only a slight chance of winning. We may offer an estimate of the amount or range of loss only if the probability of an unfavorable outcome is not remote and we believe that “the probability of inaccuracy of the estimate . . . is slight. ” ABA Statement ¶ 5. As just discussed, the probability of an unfavorable outcome is definitely not remote. Pain and suffering is so uncertain that it’s unclear what Smith would get if he wins. However, the amount of the medical bills seems certain, so it would probably be acceptable to say that, if Acme loses, the loss could be at least $130,000, as long as we make it clear that greater liability is possible. The Guaranty 9 It is probable that we will have to pay the on the guaranty. It is “fairly certain” that Beta will be unable to repay any of the principal and, i f it doesn’t, we are “clearly liable.” Therefore, Acme’s prospects of success are slight and it is extremely doubtful that the Bank will lose. We therefore can comment on the outcome, to say that it is probable Acme will have to pay the claim. We may also comment on the expected amount of the liability. Beta is unlikely to be able to pay much, if any, of the loan’s principal, so it is almost certain we will have to pay the full amount of the guaranty, $150,000. We may say that in the letter. 10 Part I, Question 4 The lender’s concern is whether the borrower will be able to repay the loan. A number of the ratios we discussed might be relevant to that concern, although some clearly are not. I graded your answer based on the relative importance of the ratios you chose and your justification of those rati os. The answer below represents one plausible set of choices. Big Bank’s primary concern is whether Acme will have the cash flow to be able to repay the principal and interest on the loan as it becomes due. The three most important ratios for making this evaluation are probably the interest coverage ratio, the cash inter est coverage ratio, and free cash flow. Interest Coverage Ratio The interest coverage ratio is calculated by dividing EBIT (earnings before interest and taxes) by the company’s interest expense. In effect, this measures interest expense as a proportion of the company’s earnings—how easily its pre-tax earnings can cover the interest it has to pay. The higher the ratio, the better. Cash Interest Coverage Ratio A similar measure is the cash interest coverage ratio, whic h is calculated by dividing cash flow from operating activities by interest expense. This compares interest expense to the company’s cash flow from operating activities. In essence, it’s a measure of how easily the company’s regular operating cash flow can cover the interest obligation. Again, the higher the ratio, the better. This is a better measure than the interest coverage ratio because interest is paid in cash; non-cash earnings don’t necessarily provide funds to repay Big Bank. Debt-Equity Ratio The third measure I would suggest is the debt-equity ratio. This is calculated by dividing the company’s total debt by its total equity. 11 Since Equity = Assets –Liabilities, the amount of equity represents, at least in theory, the net free assets after paying liabilities. (Of course, this is true only in theory, since balance sheet values are not based on actual fair value.) In this case, a lower number is better. The lower the debt-equity ratio, the greater the proportion of net assets in excess of over the company’s liabilities and, everything else being equal, the more secure the loan. 12 Part I, Question 5 Cash accounting is relatively simple. The business only has to keep track of when cash comes in and goes out. The allocation of revenue and expenses to particular periods is easy. But accrual accounting provides a much more accurate picture of the period-to-period progress of the business. Under the cash method, a huge outlay that is going to benefit the company for a number of periods, such as the purchase of a machine, is treated as an immediate expense in the period of purchase, making the business ’s earnings look incredibly bad for that period. Correspondingly, earnings look better than they should in future periods because they don’t take into account the cost of the machine tha t is being used to generate those earnings. Similarly, if a customer prepays for work, the cash method would recognize that revenue upon payment, even though the company has not yet done anything to earn the money. Accrual accounting more accurately allocates revenues and expenses from period to period. But it achieves this accuracy at the expense of complexity. Businesses must decide how to allocate costs over multiple periods and when revenues and expenses should be recognized. Those judgments are not always easy to make and are subject to manipulation. However, cash accounting is also subject to manipulation —timing collection of accounts, for example, to increase revenues when times are bad or delaying capital purchases to avoid the associated cash expense. It’s not clear which is worse in this respect. 13 Part II of the Exam The answers to the question on Part II of the exam are contained in a separate Excel file.