fall of the radical democracy 415-404

advertisement

THE FALL OF THE RADICAL

DEMOCRACY: ATHENS 415-404 B.C.

Background Briefing Topics: - Introduction - The Peloponnesian War

- The Effects of the Sicilian Expedition

- The Renewed Persian Threat

- The Rise of the Oligarchy of the Four Hundred

- The Five Thousand

- The Restoration of the Democracy

- The Victory of Sparta

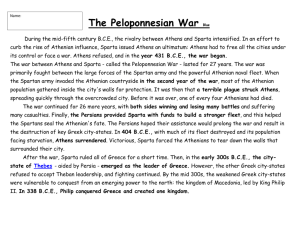

1. Introduction: The Peloponnesian War

Athenian involvement in the war against Sparta would expand until it became a war between

two extended alliances, focused in part on different political systems, but in reality a contest

for hegemony in the Greek and eastern Mediterranean worlds. Before the end of the war, the

theatre of operation would spread well beyond Greece and the Aegean into the middle

Mediterranean, as well as operations in Asia Minor and parts of the Levant. Events began to

run against Athens, first with the continued pressure against her alliance by revolts in subject

states, then with defeats in Thrace and Chalcedon, followed by unsuccessful battles in the

Peloponnese (southern Greece). The events after 415 B.C. are set out in the following table: Table 1: Greek Affairs 415-404 B.C. (Based on Rex Warner's translations of Thucydides and

Xenophon)

Date Events

415 B.C. Launching of the Sicilian Expedition

415 B.C. The Athenian fleet arrives in Sicily

415 B.C. Recall of Alcibiades to face trial in Athens

415 B.C. Athenian victory before Syracuse

415 B.C. Camarina in Sicily remains neutral, though decides to

help Syracuse secretly

415-4 Alcibiades defects to Sparta

415-4 Continued Athenian Successes at Syracuse

414 Spartan commander Gylippus with fleet arrives in Syracuse

414-3 Letter of Athenian general Nicias to Athenians pointing

out difficulties in Sicily

413 Spartans fortify Decelea in Attica, 13 miles from Athens,

controlling the countryside

413 Athenian naval defeat in the Great Harbour of Syracuse

413 Athenian reinforcements arrive at Syracuse

413 Athenian defeat in land battle of Epipolae in Sicily

413 Total Destruction of the Athenian Sicilian Expedition

411 Persian forces in Ionia and revolt of Athenian ally Chios

411 Treaty between Persian and Spartans accepting Persian

control of cities on coast of Asia Minor

411 Rule of the oligarchy of the Four Hundred in Athens

411 Samians and allied fleet uphold democratic constitution

411 Defeat of Athenian home fleet off Euboea and loss of

control of Euboea

411 Four Hundred deposed and the rule of the Five Thousand

established

411 Athenian naval victory at Cynossema (Hellespont)

411-10 Naval successes of Athenians in Hellespont under

Alcibiades

409-8 Further naval victories by Alcibiades

407 Cyrus, crown-prince of Persia, arrives to take control of

Ionian coast and help Spartans

407 Thasos in revolt from Athens

407 Alcibiades returns to Athens, appointed supreme commander

407 Lysander takes control of Peloponnesian fleet and defeats

Athenians at Notium

407 Alcibiades dismissed as Athenian commander

406 Lysander's command given over to Callicratidas, who

blockades Athenians forces at Mytilene

406 Athenians defeat Spartan fleet at Battle of Arginusae

406-5 Recall of Lysander. Athenian fleet defeated at Battle of

Aegospotami

405 Spartans control Hellespont and Aegean

405 Spartan army invades Attica, Spartan fleet attacks Aegina,

Salamis and anchors in Piraeus

404 Athens surrenders, accepts Spartan terms, begins to tear

down the Long Walls

Of all the Athenian defeats it was the disaster of the Sicilian expedition which caused the

greatest depletion of manpower, ships, and financial resources. More than this, it also created

a crisis in confidence within Athens and its alliances. Likewise, the Spartan fortified position

at Decelea (within Athenian territory itself) was beginning to cause them real problems,

presumably in conjunction with a weakened naval domination of the Aegean.

The crisis in the war also undermined confidence in Athenian radical democracy, eventually

leading to a temporary return to an oligarchic system. This had been stated in text known as

The Constitution of Athens, whose authorship is normally attributed to Aristotle. Speaking of

the Athenians, it states: Now as long as the fortune in the war was equally balanced, they retained the

democracy. But when, after the disaster in Sicily, the Lacedaemonian side became

stronger through the alliance with the Persian king, they were compelled to abolish

the democracy and establish the constitution of the Four Hundred. The speech

initiating this resolution was made by Melobius, and the resolution itself was drafted

by Pythodorus of the deme Anphlystus. What chiefly won over the masses to support

the resolution was the belief that the king of Persia would be more likely to take part

in the war on their side if they had an oligarchic constitution. (Athenian Constitution

29.1)

This is a startling change of affairs, and it is clear that Athens now felt unable to withstand

her enemies, fearing imminent defeat. But we must go beyond these general statements. To

what extent were the factors of the failure of the Sicilian Expedition and the fear of Persia

directly responsible for the oligarchic revolution of the Four Hundred?

Greece in 421 B.C. (Courtesy PCL Map Library,

http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/historical/history_europ

e.html#G)

2. The Effects of the Sicilian Expedition

Alicbiades was one of the main promoters of this scheme to conquer large sections of Sicily

and thereby bolster the power of the Athenians against the huge forces now mustered by the

Spartan alliance (Lacedaemonian Alliance). It is surprising how quickly Alicibiades emerges

into political prominence after the failure of his political schemes to break up the

Lacedaemonian Alliance. However, he managed to avoid an ostracism (a formal political

exile voted on by the Athenian city body) by arranging some kind of political alignment with

Nicias, and in 417 B.C. both were elected strategoi, generals (Bloedow 1973, p9).

It is easy to say in hindsight that this expedition would likely be a disaster, since it greatly

extended Athens theatre of operations at a dangerous time. Caution was undermined by the

excessive hopes and fears produced by the war, undermining political and military

judgement, a central theme in Thucydides' work as a whole (see MacLeod 1974; Farrar 1988,

p156; Jordan 2000). In the case of the first naval expedition, it seems likely that in spite of

appearances, it was under-funded, undermanned in terms of numbers and quality of its

hoplites and cavalry, and was voted for in the Assembly because of the expectation of 'private

and public' financial gain to be achieved (Jordan 2000). Indeed, these commercial motives

may have begun to undermine the expedition's strategic goals: Almost incidentally we hear that soldiers, sailors, and merchants also take money

along for the purpose of trading overseas . . . the military expedition has virtually

become a commercial venture, and in fact more than that, . . . we see that many noncombatants, not only merchants looking for profit, but also masons, builders, millers,

and so on, voluntarily accompanied the fleet in many cargo ships. The expedition . . .

amounted to a large-scale effort to plant an Athenian colony in Sicily; it was, in effect,

a 'city on the move' (Jordan 2000, p66, following Thucydides VI.31 & VI.44 and Avery

1973)

Moreover, it seems clear that Alcibiades both used this expedition to bolster his own

popularity, and at the same time felt that he could break the dominance of Syracuse over the

eastern area of Sicily, essentially by creating an alliance of smaller Greek cities and the native

Sicels of the interior (Bloedow 1973, pp9-11). This would allow Athens to extend it alliance

and access he resources and manpower of the wealthy island. This scheme however, and even

while Aliciades was in command, was not well accepted by many Sicilian cities; Messana,

Naxos and Catana did not come over onto the Athenian side, perhaps because Athens had

already gained a rather negative reputation as a harsh imperialist (Bloedow 1973, pp11-12)

due to her treatments of cities such as Mytilene and Melos. Alicibiades, moreover, had been

arraigned on charges of impiety just before the fleet was to leave, but had been unable to

secure a trial before he left Athens as one of the expedition's generals. Knowing that his

political enemies would have made advantage of his absence to bolster the charges against

him, he chose not to accept the summons to return for trial, but defected to the Spartan side

(for a time).

Thucydides says that a total of 40,000 men were engaged in the siege of Syracuse, and that

these were totally defeated (Thucydides VII.87). The magnitude of such a disaster is

expressed in the speech by one of their generals, Nicias, who suggests that the defeat in Sicily

could lead on to a defeat in Athens as well (Thucydides VII.64). A later source, Diodorus

Siculus, believed that the defeat in Sicily caused the Athenians to voluntarily set up the Four

Hundred: Choosing four hundred men they put in their hands the supreme authority to direct

the conduct of the war; for they assumed that an oligarchy was more suitable than a

democracy in critical circumstances like these. (Diodorus Siculus, XIII.36, p219)

This simplified view, however, ignores the time gap between the defeat in Sicily and the

advent of the Four Hundred, and also underestimates the vigour with which the Athenian

democracy tried to meet this disaster. Thucydides states that: Nevertheless, with their limited resources, they must not give in; they would equip a

fleet, getting the timber from wherever they could; they would raise money, and see

that their allies, particularly Euboea, remained loyal; and in Athens itself they would

take measures of economy and reform. (Thucydides VIII.1)

The defeat at Syracuse, then, was one important factor in setting up the pre-conditions for the

fall of the radical democracy, but did not lead directly to the oligarchic revolution itself.

Rather, in threw doubt on the ability of the democracy to wisely set policy and choose

generals. Nicias, who had been against the expedition, was over-ruled by the Assembly, even

though he too was sent out as one of the commanders to Sicily.

3. The Renewed Persian Threat

Too much weight should not be placed on the statement in The Athenian Constitution that 'the

Lacedaemonian side became stronger through the alliance made with the Persian king.' (29.1)

Certainly treaties were made and funds were supplied (Thucydides VIII.18,37,58), but

Persian aid was both rather indirect and at times tardy. The Persian satraps involved did not at

first pay the Peloponnesian fleet adequately (Thucydides VIII.8,29,46,83), and did not bring

the promised Phoenician fleet into operations in the Aegean (Thucydides VIII.87,146).

Thucydides believes that the intervention of the Phoenician fleet would have swiftly brought

an end to war in Sparta's favour, but that this was not done on the advice of Alcibiades, who

had influence with the Persians and argued that a balance should be kept between Sparta and

Athens to try and wear them both down (Thucydides VIII.87). It is likely that Alcibiades was

playing a 'triple game' in order to avoid the total defeat of his home city, and preparing

conditions for a possible return to political eminence in the city.

The demos of Athens, along with their naval forces stationed at Samos, probably felt that the

king of Persian would be more likely to support them if they had an oligarchic constitution

(Thucydides VIII,49 &53). They were aware, firstly, that Persian-controlled naval forces

could tip the balance against them in the Aegean, but were equally concerned about the

influence of Persian financial resources. The Athenians were strongly aware of the financial

requirements of a long war, and the Persian resources, even those derived from Asia Minor,

greatly exceeded theirs.

3. The Rise of the Oligarchy of the Four Hundred

A third reason, however, needs to be added to this account of the destabilizing of the

Athenian democracy. In Thucydides we find a major theme expressed by the Syracusan

Hermocrates, who says that: We should realize that internal strife is the main reason for the decline of cities.

(Thucydides IV, 61).

This internal problem, according to Thucydides, was fuelled by bad public decisions based on

the private ambition and the private policies of the leaders who followed Pericles

(Thucydides II.64), especially Cleon and Alcibiades. Plutarch reports the humorous tale that a

certain misanthrope called Timon, came up to Alcibiades and said, 'You are doing well, my

boy! Go on like this and you will soon be big enough to ruin the lot of them.' (Alcibiades, 16)

Indeed, Alcibiades had been one of the main promoters of the Sicilian expedition, so the jibe

was not entirely untrue. In passing we might also note that once Alcibiades had joined the

Spartan side to avoid political prosecution at Athens, he did give very good advice to the

Spartans. This included the policy of fortifying Decelea in Attica, which cut off the silver

mines at Laurium, and stopped the Athenians using their countryside year round. Likewise,

his advice to the Peloponnesians to support the revolt of Chios and Miletus forced the

Athenians to station a strong force of 100 triremes permanently at Samos (Thucydides

VIII.8,16,20).

However, Alcibiades outstayed his welcome at Sparta, and eventually engineered his

welcome back at Athens. Alcibiades had 'his views <made> known to the best people in the

army and to say that, if there was an oligarchy instead of the corrupt democracy which had

exiled him, he was ready to return to his country and take part with his countrymen and make

Tissaphernes <the Persian satrap> their friend.' (Thucydides VIII.47)

It was such words which would have helped motivate the leaders of the political 'clubs' who

favoured an oligarchic form of government. Thucydides notes that: The idea of an oligarchy was very badly received by the people at first, but when

Pisander had made it perfectly clear that there was no other way out, their fears (and

also the fact that they expected to be able to change the constitution again later)

made them give in. They voted that Pisander and ten others should sail out and make

whatever arrangements seemed best to them with Tissaphernes and Alcibiades.

(Thucydides VIII.54)

After securing control through a change of generals of the Athenian fleet, members of the

oligarchic faction went on to secretly kill Androcles, one of the main speakers for the

democratic faction. This man had also been an opponent of Alcibiades (Thucydides VIII.65).

According to The Constitution of Athens the leaders of this oligarchic coupe included very

able men such as Pisander, Antiphon, and Theramenes ((Athenian Constitution, 32).

Ironically, this group operated independently of Alcibiades, though they used his name and

influence to further their own policies. They later on tried to keep Alcibiades out of power,

but were unable to do so in the end (Alcibiades ended up becoming a general of the

democratic fleet, stationed at Samos, and become one of the main threats to the Four

Hundred.)

The critical situation created by the difficulties of the war gave the oligarchs and their

political clubs the opportunity and pretext to seize power. The selection of the Four Hundred

men to rule occurred in the following way, according to Thucydides: That five men should be selected as presidents; that these should choose 100 men,

and each of the 100 should choose three men; that this body of 400 should enter the

Council chamber with full powers to govern as they thought best. (Thucydides VIII.67)

This view is not supported by the Athenian Constitution, which states: Four hundred men should form the Council according to the ancestral order, 40 from

each of the tribes, elected of bodies of candidates over thirty year old previously

selected by their tribesmen. (Athenian Constitution 31.1)

It is not really possible to reconcile these two varying accounts. Though the Athenian

Constitution's account does seem to confirm more closely to the traditional Council of the

Four Hundred set up under Solon, this does not mean that this account is more likely - it may

be here following what it would have expected to have been the 'valid' structure of such a

council (see Fuks 1953 for the past as a model of current and future reform in the Greek

world).

The real nature of the Four Hundred is clearly shown by their choice of 'an Assembly' area at

Colonus, a ground about a mile from the city (Thucydides VIII.67). Such a meeting place,

outside the walls, with the Spartan army situated at Decelea, would have prevented large

numbers of Athenians from attempting to attend, especially those without horses or armour as

protection. Furthermore, large numbers of adult citizens would have needed to keep on

manning the walls of the city, and the Long Walls which headed down to the coast, and

would not be able to leave their posts long enough to reach the external assembly area

(Thucydides VIII.69).

The real issue is, 'Which body passed the motion to select the Four Hundred?'. If it was the

full Assembly, then the radical democracy voted itself out of existence for reasons of

expediency and national survival. Another possibility is that an assembly of 5,000, probably

including the rich and the better off of the hoplites, might have voted to give the Four

Hundred these powers. Alternatively, it may be that the voting was nothing more than a

fiction designed to cover up some kind of take-over, led by an oligarchic group who could

always open the city to the Spartans if required. It is not easy to settle this question

definitively. However, the venue of the Four Hundred at Colonus suggests that the motions

passed by this body should not be viewed as motions passed by the 5,000. At this time the

Five Thousand was little more than a thin veneer of legality given to what was in effect an

oligarchic revolution.

Thus the Four Hundred, along with the ten men who had been given extra-ordinary powers,

entered the Council house and ruled the city (Athenian Constitution 31.3). The substantially

personal nature of their ambitions is stated by Thucydides. When their position was

threatened they were willing to discuss terms with Sparta on the following basis: What they really wanted in the first place was to preserve the oligarchy and keep

control over the allies as well; if this was impossible their next aim was to hold onto

the fleet and fortifications of Athens and retain independence; but if this also proved

beyond them, they were certainly not going to find themselves in the position of being

the first people to be destroyed by a reconstituted democracy, and preferred instead

to call in the enemy, give up the fleet and fortifications and make any sort of terms at

all for the future of Athens, provided that they themselves at any rate had their lives

guarantied to them. (Thucydides VIII.91-2)

The historian G. Grote has accurately assessed the success of this group: The ulterior success of the conspiracy - when all prospect of Persian gold, or

improved foreign position, was at an end - is due to the combinations alike nefarious

and skilful, of Antiphon, wielding and organizing the united strength of the aristocratic

classes at Athens; strength always exceedingly great, but under ordinary

circumstances working in factions disunited and even reciprocally hostile to each

other - restrained by the ascendant democratic institutions - and reduced to corrupt

what it could not over-throw. (Grote 1967, p69)

The Four Hundred operated not so much through popular acceptance, as through popular

fear. Fear of Sparta and Persia, the fear generated by the assassination of Androcles, the

existence of a band of 'Hellenic' youths armed with daggers who were the strong-arm of the

oligarchs, with the democratic elements in the end frozen by the possibility that the Five

Thousand were not just a myth but a reality by this stage. (Thucydides VIII.92)

4. The Five Thousand

The rule of the Four Hundred lasted for four months and was soon replaced by the rule of the

Five Thousand. According to The Constitution of Athens, the main reason for the removal of

the Four Hundred were their failures in conducting the war: -

When they <the Athenians> were defeated in the naval battle off Eretria, and when

the whole of Euboea with the exception of Oreos revolted, the Athenians were more

embittered by the revolt than by anything that had happened before, for they drew

more support from Euboea than from Attica itself. And, in consequence, they

abolished the rule of the Four Hundred, entrusting the government to the five

thousand capable of doing military service with full equipment, and decreed at the

same time that there was to be no pay for any public office. (Athenian Constitution

33.1)

If this is accurate, then the 5,000 is a rather low number for Athens' available hoplites, but at

this stage of the war, after many losses, and with sizeable numbers of hoplites serving in the

fleet and foreign garrisons, the number is not impossible. It is also possible that 5,000 was a

nominal 'round figure' that fitted in with the classical view of a moderate Athenian

democracy. Thus, these 5,000 might represent a narrower conservative body within the fiscal

class which can support hoplite status.

Thucydides agrees with the importance of the loss of Euboea, but gives a somewhat different

chronology of events. He believes that this revolution was initiated by the Five Thousand and

began with the tearing down of fortifications which gave the Four Hundred the control of the

harbour. This was done in the name of the Five Thousand, the body which the Four Hundred

had promised but which had not been allowed to meet yet (Thucydides VIII,92-4). The prodemocratic forces then decided to march on the city, but were forestalled by messengers from

the Four Hundred with the following political accommodation:

They <the Four Hundred> would publish the names of the Five Thousand and that

the Four Hundred would be chosen from them in rotation, just as the Five Thousand

should decide. (Thucydides VIII.93)

Thus the replacement of the Four Hundred was already underway, and the loss of Euboea was

sufficient to undermine whatever broader support they may have had. The reasons for this

revolution probably included a veiled desire on the part of some for a return to the

democracy, and upon the personal political ambitions of two leaders, Theramenes and

Aristocrates (Thucydides VIII.89). The Constitution of Athens infers that these men

promoted the change due to a genuine desire for moderation (Athenian Constitution 33.2).

Alcibiades also had a hand in this revolution. Having been excluded from power by the

oligarchs at Athens, and having been recalled to the democratic faction in the fleet at Samos,

he once again changed his policy. In reply to the envoys of the Four Hundred he had said: He was not opposed to the government being in the hands of the Five Thousand, but

he did demand that they should get rid of the Four Hundred and that the original

Council of the Five Hundred should be reinstated. (Thucydides VIII.86)

The desire that Athens shouldn't be turned over to the Spartans, and the fact that the oligarchs

could not survive, may have been the main motivations for Theramenes to come to a more

moderate position. Alcibiades control of the fleet at Samos may also have been a convincing

factor. According to Thucydides: The assembly met at the Pynx, where they used to meet before. The Four Hundred

were deposed and it was voted that power should be given over to the Five Thousand

. . . (Thucydides VIII.97)

There are varying modern views on what this actually meant. G.E.M. de Ste. Croix believes

that this revolution was really a return to democracy, except for the absences of jury pay,

'although effect control of affairs was reserved for the upper classes' (Ste Croix 1956, p2).

P.J. Rhodes, however, claims that the hoplite assembly became the sovereign body during

this period and that the ('lower') thete class lost the vote (Rhodes 1972, p122). However, I

would suggest that the upper classes could not have kept direct control with a full assembly

sitting. Nor does the number 5,000 equate with either the current or traditional numbers of

hoplites in Athens.

What does seem clear from the account in the Constitution of Athens is that the rule of the

Five Thousand was regarded as something separate from the full democracy. Furthermore,

there is some evidence for a 'third party' in Athens, who neither supported a narrow oligarchy,

nor a full democracy. According to the trial speech made by Lysias, there was such a third

party led by Theramenes and Aristocrates (Lysias For Polystratus, XX). In Xenophon,

Theramenes makes the following speech: "But I, Critias, am forever at war with the men who do not think there could be a

democracy until the slaves and those who would sell the state for lack of a shilling

should share in the government, and on the other hand I am forever an enemy to

those who do not think that a good oligarchy could be established until they should

bring the state to the point of being ruled absolutely by the few." (Xenophon

Hellenica, II.4.47-50)

Although political leaders such as Theramenes might be very fickle, we should note that both

Thucydides (VIII.89-90) and the Constitution of Athens (33.2) state that this man played a

crucial role of the ending of the rule of the Four Hundred. If so, half of the above statement

was backed up by appropriate action. It seems unlikely that he would have re-introduced a

full democracy. Likewise, the absence of any precise dates in our ancient sources for the

return of the full democracy only suggests that the return was a gradual one (Kurt & Kapp,

1974, pp180-1, note 117).

Another issue of significance is whether the Council of the Five Hundred operated under the

Five Thousand - if it did their 'hoplite Assembly' would have been the sovereign body in the

state, without undue oligarchic influence. Certainly we do hear of a Council in 406 B.C.

recommending motions to the Assembly in the prosecution of 8 generals, but their actions do

not tell us whether they were a properly constituted Council of Five Hundred or not

(Xenophon Hellenica I.7). Summing these issues up, whether the rule of the Five Thousand

involved depriving the thetes of the vote or not, it still involved a type of government

different in fact from a full, direct democracy.

5. Restoration of Democracy

The final restoration to a full democracy was probably not a revolution as such, but a more

peaceful return to a still rather moderate democracy. It included the return of pay for political

offices, and a vote in the assembly for the thetes, many of whom, we must remember, were

rowers in the war fleets. Full rights may have only been restored in the face of a massive

Spartan victory in 405 B.C., but that this was done would indicate that democratic institutions

and ways of thinking were deeply ingrained in Athenian thought. The Spartan victory and the

tyranny by The Thirty would be only short breaks in the continuation of an effective

Athenian democracy that operated down till the late fourth century.

It is certainly true that Athenian democracy was quite radical once again by 399 B.C., and

was willing to hunt down the enemies of the democracy, or those associated with antidemocratic persons, including thinkers such as Socrates. However, once the impacts of the

defeat in the Peloponnesian War and the tyranny of The Thirty had been absorbed, Athenian

democracy set itself on a more moderate path. In particular, it dampened the use of trials as a

political weapon, and a calmer adjustment was made between elite leadership and democratic

participation. Recent history had taught the Athenians that powerful cities decline more due

to internal division, not just due to external threats.

6. The Victory of Sparta

The victory of Sparta was based on her gaining naval superiority in the Aegean and

Hellespont. If she could close the Hellespont leading onto the Black Sea, then she could

choke Athens' external grain supply, crucial now that her garrison at Decelea excluded any

use of Attican harvests. Normally, the Athenians kept a small group of nine ships in the

Hellespont to guard their merchantmen (Xenophon Hellenica I.1), but after 411 B.C. they

sent more ships there to counter Spartan efforts in the region.

Spartan war aims were completed with the effective support of the Persian Cyrus, who

provided 500 talents and considerable land forces to the war effort. It was largely these funds

which allowed the Spartans to maintain such a large and effective navy. Good leadership was

also shown by the Spartan commanders Lysander and Calicratidas in 407 and 406 B.C. We

can see how stretched Athenian naval forces were after the blockading of their fleet,

commanded by Conon at Mytilene: When the Athenians heard what had happened and of how Conon was under

blockade they voted in favour of sending 110 ships to his relief, and put aboard these

ships all men of military age, slave or free. . . . there were even many men who were

entitled to serve in the cavalry who took part in this expedition. (Xenophon Hellenica

I.6)

It is clear then that Athens was not only short of hoplites, she was also very short of rowers.

This may help account for the rather vicious behaviour of the Athenian Assembly in 406

B.C., when, even though they had been victorious at the Battle of Arginusae, six generals

were put to death on charges of not picking up survivors who had been lost at sea (Xenophon

Hellenica I.7). Theramenes, who helped bring the charges, was also saving his own skin,

while removing some political competition.

This reprieve, however, was a temporary one. In 405-4 B.C. Lysander led the Spartans to a

decisive victory in the Hellespont - at the Battle of Aegospotami he effectively destroyed

most of the Athenians fleet. The Spartans now controlled the Hellespont, Byzantium and

Calchedon (Xenophon Hellenica II.1): Athenians main food supply had been cut. Lysander

then sailed out of the Hellespont with 200 ships and settled affairs in the Aegean as he

wished. Only Samos held out, with the people slaughtering their aristocratic party and taking

control of the government. After Athens' decisive naval defeat 'every state in Greece except

Samos had abandoned the Athenian cause' (Xenophon Hellenica II.2). The Peloponnesian

army once again invested Attica, but now a large fleet worked along side them. The fleet

restored the independence of Aegina and Melos, devastated Salamis, and anchored at Piraeus

with 150 ships. Athens was now completely cut off. A city with such a large population,

whose reserves had already been worn down by years of fighting, would soon find itself at

the point of starvation.

Athens did try to resist for a time. In an order to avoid internal stasis and to mobilize as many

people as possible, rights were given back 'to all who had been disfranchised and, though

numbers of people in the city were dying of starvation, there was no talk of peace' (Xenophon

Hellenica II.2). At this time then, if not before, the rule of the Five Thousand certainly

reverted back to a full democracy. Eventually, however, Athens had no choice but to ask for

peace terms from their enemies. The Thebans and Corinthians wanted Athens completely

destroyed. The Spartans terms were comparatively mild: They offered to make peace on the following terms: the Long Walls and the

fortifications of Piraeus must be destroyed; all ships except twelve surrendered; the

exiles to be recalled; Athens to have the same enemies and the same friends as

Sparta and to follow Spartan leadership in any expedition Sparta might make either

by land or sea. (Xenophon Hellenica II.2)

I suspect that Sparta knew that the complete destruction of Athens would make Sparta feared

by the smaller Greek cities: but more importantly, the removal of this important power might

shift the balance too far in the favour of Corinth and Thebes (Thebes, in fact, would seriously

defeat the Spartans in the next century.)

For the time being, however, Greece was at peace. It was probably for this reason that the

walls of Athens 'were pulled down among scenes of great enthusiasm and to the music of

flute girls. It was thought that this day was the beginning of freedom for Greece. (Xenophon

Hellenica II.2) This was only partially true, and only for a relatively short time.

7. Bibliography and Further Reading

Ancient

ARISTOTLE (trans. K von Fritz & E. Kapp) The Constitution of

Athens, N.Y., Hafner Press, 1974

DIODORUS SICULUS Histories, (trans. C.Oldfather) Vol 5,

Cambridge MA, Harvard University Press, 1962

LYSIAS, (trans. W.Lamb) For Polystratus, Cambridge MA, Harvard

University Press, 1967

PLUTARCH Plutarch's Lives, trans. by Bernadotta Perrin, 7

vols., London, Heinemann, 1914

PLUTARCH The Rise and Fall of Athens: Nine Greek Lives, trans.

by Ian Scott-Kilvert, Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1960

THUCYDIDES, (trans. R.Warner) History of the Peloponnesian War,

Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1988

XENOPHON, (trans. C.Brownson) Hellenica, Cambridge MA, Harvard

University Press, 1968

XENOPHON, (trans. R.Warner) A History of My Times (Hellenica),

Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1966

Modern

AVERY, H.C. "Themes in Thucydides' Account of the Sicilian

Expedition", Hermes, 101, 1973, pp1-13

BLOEDOW, Edmund F. Alcibiades Reexamined, Wiesbaden, Franz

Steiner Verlag Gmbh, 1973

CARY, M. "Notes on the Revolution of the Four Hundred at

Athens", Journal of Hellenic Studies, 72, 1952, pp56-61

FARRAR, Cynthia The Origins of Democratic Thinking, Cambridge,

CUP, 1988

FUKS, Alexander The Ancestral Constitution, London, Routledge &

Kegan Paul, 1953, pp1-25

GOMME, A.W. "The Working of Athenian Democracy", in More Essays

in Greek Literature, Oxford, 1962

GROTE, G. "The Threat of the Oligarchs" in J. Claster, Athenian

Democracy: Triumph of Travesty?, New York, Holt, Rinehart and

Winston, 1967

HARDING, P. "The Theramenes' Myth", Phoenix, 28, 1974, pp101111

JORDAN, B. "The Sicilian Expedition Was a Potemkin Fleet", The

Classical Quarterly, Vol. 50, No. 1., 2000, pp63-79

MACLEOD, C.W. "Thucydides' Plataean Debate", GRBS, 18, 1977,

pp227-246

OBER, Josiah Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens: Rhetoric,

Ideology, and the Power of the People, Princeton, Princeton

University Press, 1989

RHODES, P.J. "Athenian Democracy after 404 BC", Classical

Journal, 74, 1979-80

RHODES, P.J. "The Five Thousand in the Athenian Revolution of

411 B.C.", Journal of Hellenic Studies, 92, 1972, pp115-127

STE CROIX, G.E.M. de "The Constitution of the Five Thousand",

Historia, 5, 1956, pp1-23

Essays in History, Politics and Culture Copyright R.

James Ferguson © 2001