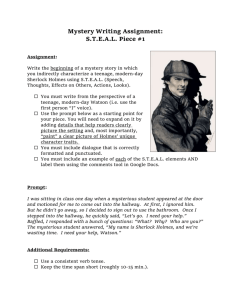

Brewer, Session 8.1.2 (post 07-24-14)

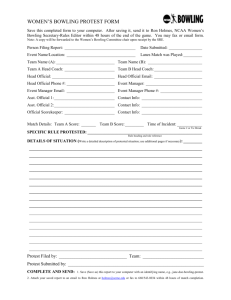

advertisement

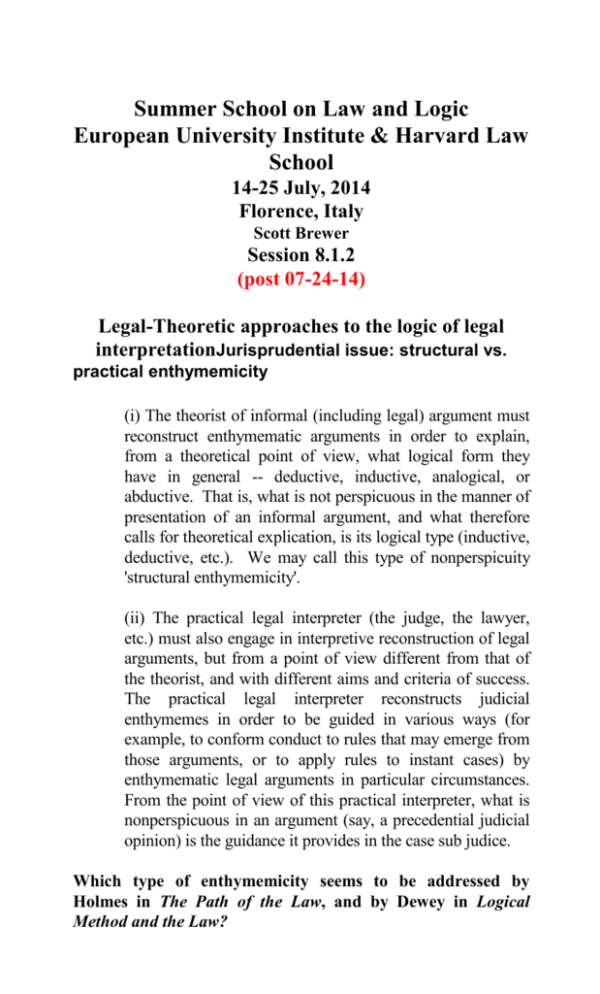

Summer School on Law and Logic

European University Institute & Harvard Law

School

14-25 July, 2014

Florence, Italy

Scott Brewer

Session 8.1.2

(post 07-24-14)

Legal-Theoretic approaches to the logic of legal

interpretationJurisprudential issue: structural vs.

practical enthymemicity

(i) The theorist of informal (including legal) argument must

reconstruct enthymematic arguments in order to explain,

from a theoretical point of view, what logical form they

have in general -- deductive, inductive, analogical, or

abductive. That is, what is not perspicuous in the manner of

presentation of an informal argument, and what therefore

calls for theoretical explication, is its logical type (inductive,

deductive, etc.). We may call this type of nonperspicuity

'structural enthymemicity'.

(ii) The practical legal interpreter (the judge, the lawyer,

etc.) must also engage in interpretive reconstruction of legal

arguments, but from a point of view different from that of

the theorist, and with different aims and criteria of success.

The practical legal interpreter reconstructs judicial

enthymemes in order to be guided in various ways (for

example, to conform conduct to rules that may emerge from

those arguments, or to apply rules to instant cases) by

enthymematic legal arguments in particular circumstances.

From the point of view of this practical interpreter, what is

nonperspicuous in an argument (say, a precedential judicial

opinion) is the guidance it provides in the case sub judice.

Which type of enthymemicity seems to be addressed by

Holmes in The Path of the Law, and by Dewey in Logical

Method and the Law?

2

Structural is the central theme.

Dewey, as we shall see, seems to believe that no

legal argument, no "practical argument," is ever

deductive.

Defeasibility (factual defeasibility – contrast legal rule

defeasibility)

Exercise. Consider this argument:

(P1) Jones confessed to shooting Smith

(P2) Each of five witnesses testified

that he or she saw Jones shoot Smith

(P3) Jones' fingerprints were found on

the gun recovered at the scene of

Smith's shooting.

Therefore, (C) Jones shot Smith

(1) If P1, P2, and P3 were all true, how strong would they be as

"evidence" for the Conclusion C

(2) Now suppose that the whole set of P1 through P7 are true

(including, that is, P1, P2, and P3). In that case, with the larger set

of propositions as a background, how strong would P1, P2, and P3

be as "evidence" for C, under the conception of "evidence"

reflected in the FRE?

P4

Jones was beaten by the police and ordered to

confess.

P5

Each of the five witnesses was bribed by the

prosecutor to testify that he she saw Jones shoot Smith.

P6

Fingerprint evidence is reliable only 40% of the

time.

P7

The technicians in laboratory to which the gun was

sent for fingerprint analysis were both incompetent and

corrupt.

3

Defeasible argument:

Less formal definition: An argument from premises to a

conclusion is defeasible if and only if the argument is one in

which it is possible that the addition of some premises to the

argument's original premises can undermine the degree of

evidential warrant that the original premises provide for the

conclusion.

More formal definition: An argument from premises P1-Pn to

conclusion C is defeasible if and only if the argument is one in

which it is possible that the addition of some premise(s), Pn+1,

to P1-Pn, can undermine the degree of evidential warrant

premises that P1-Pn provide for C.

Queries:

(i) Is it possible that a deductively valid inference is defeasible -i.e., is it possible to add any premise to a deductively valid

inference that undermines the force of the evidential warrant the

original premises provide for the conclusion?

(ii) In the example of Jones and Smith offered above, is the

argument from P1, P2, and P3 as premises to the conclusion h

defeasible or indefeasible?

One question has been central to both general jurisprudence and

the jurisprudence of logical form: Whether and to what extent

legal arguments, especially the legal arguments offered by judges,

can be adequately represented as valid deductive inferences.

Can some such arguments be thus represented? Many? A large

percentage? None? Legal Realists like Holmes and John Dewey,

as well as other major jurisprudential thinkers like H.L.A. Hart,

Ronald Dworkin, and judge-theorists like Antonin Scalia, believe,

and some of them explicitly argue, that something important is at

stake in providing a philosophical explanation of legal argument

that correctly answers this question. Why might they think this

question important, and why might we?

For the philosophers in this group (though this may motivate

others less), one answer is just that, as a matter of increasing the

4

stock of philosophical knowledge, it is valuable to be able to

understand and explain the structure of a type of reasoning, legal

and more specifically, judicial, that seems (at least, seems "pretheoretically") to be a central component of legal decision-making.

In this way answering the question derives some of its value from

the value human communities have placed on the practices and

institutions of law for thousands of years. That value, the

millennial value of understanding legal practices and institutions,

is reflected in the robustness of the debate about how best to

explicate the concept of "law."

Another answer, closely related to the first, links two values that

are and have been widely held, indeed are and have been almost

pervasive in many human cultures for thousands of years.

One value is the value to a society of institutions and practices of

law, the other is the value to a society of institutions and practices

of reason and the faculty of reasoning.

These values become linked synergistically: we want to know

whether and to what extent the institutions and practices of law

that seem so important to society are capable of being guided by

reason and, for given legal systems, whether and to what extent

they are in fact guided by reason.

Now, the concept of "reason" itself is obviously highly abstract

and has been the subject of never ending attention and speculation

probably since humans acquired self-reflective cognitive powers.

It certainly has been a core philosophical interest for several

thousand years.

And while it's long been clear there are many types of reason and

many types of reasoning, one type has been regarded by many

philosophers and others in the broader culture as prima inter

pares: deductive reason and deductive reasoning. Perhaps the first

time that philosophers and others saw the power of deductive

reason literally graphically illustrated was with the publication of

Euclid's Elements in ancient Greece.

Geometric reasoning, and its axiomatic deductive method, came to

be a dominant metonym for "reason" itself, or anyway reason at its

5

best. Since that time a great many disciplines, including empirical

science, social science, philosophy, and law,1 have sought to

harness the power of deductive systems to advance their projects

of explanation and social coordination. So while it may seem to be

a relatively technical and narrow concern, what a great many

theorists -- including Legal Realists, Legal Positivists, and Natural

Lawyers -- all regard the question (1) as of vital theoretical and

practical importance. For reasons (!) just noted, question (1) has

in turn been associated with another

What did the legal realists deny?: Conceptualist vs.

Legal Realist claims about deduction in legal argument

John Maxcy Zane was a "conceptualist" legal theorist, as that term

is defined by Hart.2 Zane seemed to believe that legal arguments

could be accurately represented as an a priori deductive system.

Zane's conceptualism is revealed in his succinct (if somewhat

unclearly phrased) declaration that

[I]t must be perfectly apparent to anyone who is willing to

admit the rules governing rational mental action that unless

the rule of the major premise exists as antecedent to the

ascertainment of the fact or facts put into the minor

premise, there is no judicial act in stating the judgment.

(Zane, German Legal Philosophy, 16 Mich. L. Rev. 287

(1918) (emphasis added))

1

See for example the very illuminating discussion in Hoeflich, Law and

Geometry: Legal Science from Leibniz to Langdell 30 Am. J. Legal Hist. 95

(1986).

2

Hart's definition in The Concept of Law, Chapter VII, is:

Different legal systems, or the same system at different times, may

either ignore or acknowledge more or less explicitly . . .[the] need for

further exercise of choice in the application of general rules to

particular cases. The vice known to legal theory as formalism or

conceptualism consists in an attitude to verbally formulated rules

which both seeks to disguise and to minimize the need for such choice,

once the general rule has been laid down." (COL, 2nd ed. @ 129)

6

It seems that the likeliest interpretation of Zane's phrase 'no

judicial act' is that a judge who offers a legal argument to resolve a

case that is not a deductive argument hasn't even succeeded in

making a (judicial) legal argument at all.

The "Zany"

conceptualist view, as we might call it, seems to be that:

(i) Deductive form is a necessary condition of a "judicial

act."

Note that proposition (i) entails:

(ii) No judicial-legal arguments are defeasible.

By sharp contrast to a Zane-like view, many legal theorists,

including many or most or even all Legal Realists, hold the view

that many, perhaps most or even all, judicial legal arguments are

defeasible. We can articulate two possible versions of the claim

that judicial legal arguments are defeasible (the "defeasibility

thesis"), which I'll call the "strong version" and the "moderate

version."

Defeasibility thesis (two versions)

Strong version: (iii) No judge's legal argument can be

accurately represented as a valid deductive inference

note that (iii) entails

(iv) All judicial-legal arguments are defeasible.

Moderate version: (v) In every set of a judge's legal

arguments that are offered to resolve a case, there is at

least one very important argument that cannot be

adequately represented as a valid deductive inference; note

that (v) entails

(vi) In every set of a judge's legal arguments that

are offered to resolve a case, there is at least one

very important argument that is defeasible.

7

Query: to which version of the defeasibility thesis is Holmes, or Dewey,

committed?

To which version does they seem committed when they both

assert that "general propositions do not decide concrete cases"?

What does it even mean to say that a general proposition does not

"decide" a concrete case? (What would it mean to say that a

general proposition does "decide" a concrete case?)

Perhaps it means that general propositions, applied as major

premises in a syllogism (as the general proposition 'All men are

mortal' appears in the syllogism "All men are mortal; Socrates is a

man; therefore, Socrates is mortal") are never decisive in a

"concrete" cases?3

But even on that reading questions remain. Does Holmes mean

that general propositions, applied as major premises in a

syllogism, play no role at all in deciding "concrete" cases (this

would be what I called the strong version of the defeasibility

thesis), or play no significant role in deciding concrete cases, even

though they may play an incidental role (this would be the

moderate version of the defeasibility thesis)?

Dewey who offers the most focused discussion of the type of logic

that is needed to represent adequately judges' legal arguments.

Neil MacCormick correctly notes that Dewey's article Logical

Method and Law "is one of the great foundational texts of

American legal realism." [Rhetoric and the Rule of Law 33.]

In the discussion that follows, my principal concern is Dewey's

view of legal argument and the role of valid deductive inference

therein.

3

Holmes seems to suggest something like this in this famous passage in The

Path of the Law: "You can give any conclusion a logical form, " but "[b]ehind

the logical form lies a judgment as to the relative worth and importance of

competing legislative grounds, often an inarticulate and unconscious judgment,

it is true, and yet the very root and nerve of the whole proceeding."

8

But like other Legal Realists, Dewey is unclear in which version

of the defeasibility thesis he endorses.4 Nevertheless, for reasons

I'll offer below, I believe he may fairly and accurately interpreted

to endorse the strong version of that thesis, labeled (iiia) above.

So now, from a logical point of view, the issue is joined between

the conceptualist and the (Deweyan) Legal Realist about as starkly

as possible. While the Deweyan Legal Realist endorses:

Holmes-Dewey Legal Realist (???): (iv) All judicial-legal

arguments are defeasible

"Zany" conceptualist: (ii) No judicial-legal arguments are

defeasible.

We could not have a (logically) stronger opposition between a

Zaney conceptualist view and a strong Legal Realist view like the

view Dewey appears to hold. Encountering such a stark clash of

claims about the nature of judicial legal arguments engenders for

us this question: What kind of philosophical argument can we

make to "adjudicate" such extremely opposed views?

Both Hart and the "deductive punctuated equilibrium" model of

legal argument provide such arguments, as does Dewey in Logical

Method and Law. I now turn to consider Dewey's argument in

detail. After doing so, and after having argued that there are very

significant problems with his explanation of legal argument, I'll

present two closely related competing views of legal argument

that attempt to avoid the kind of mistake Dewey makes.

4

Neil MacCormkick notes this unclarity in Dewey's thesis and tentatively

attributes to Dewey the weak thesis (iva), but to Legal Realism, for which

Dewey was such a powerful influence, the strong thesis (ii):

I follow [Dewey] in thinking the certainty we can have in law is, at

best, qualified and defeasible certainty. Perhaps this was the very

thing [Dewey] had in mind. Surely it was at leas part of what he had

in mind. Anyway, it has become a dominant theme in American

jurisprudence right through the twentieth century that logic and

formalism had no place in law. [MacCormick, Rhetoric and the Rule

of Law 33 (emphasis added)]

9

Holmesian anti-logic and the "fallacy of logical form"

theses

It is now a commonplace that Holmes’s declaration, "The life of

the law has not been logic; it has been experience" is what Tom

Grey has aptly called the "central slogan of legal modernism."5

Holmes first offered it in a review of Langdell's book on

contracts,6 and repeated it prominently at the opening of The

Common Law, where it serves as part of an extended admonition

about the limitations of "logic" in the best explanation of common

law doctrines:

"The object of this book is to present a general view of the

Common Law. To accomplish that task, other tools are

needed besides logic. It is something to show that the

consistency of a system requires a particular result, but it is

not all. The life of the law has not been logic: it has been

experience. The felt necessities of the time, the prevalent

moral and political theories, intuitions of public policy,

avowed or unconscious, even the prejudices which judges

share with their fellow men, have had a good deal more to

do than the syllogism in determining the rules by which

men should be governed. The law embodies the story of a

nation's development through many centuries, and it

cannot be dealt with as if it contained only the axioms and

corollaries of a book of mathematics."7

I shall refer to this basic thesis as Holmes’s "anti-logic."

The anti-logic thesis is not a passing fancy on Holmes part.

Rather, he maintained and repeated it (though not always in the

5

Thomas Grey, "Langdell's Orthodoxy," University of Pittsburgh Law Review

45 (1983): 1-3.

6

Oliver W. Holmes, Book Review, American Law Review 14 (1880): 233-234

(reviewing C.C. Langdell, Summary of the Law of Contracts (1880)).

7

Oliver W. Holmes, The Common Law, ed. Mark DeWolfe Howe (Boston:

Little, Brown and Company, 1963), 5. Holmes iterates the assertion, with an

application to contract law, about logic and experience: "The distinctions of the

law are founded on experience, not on logic." Ibid., 244. Again, in slightly

different terms, he repeats it, observing (optimistically) that "the law is

administered by able and experienced men . . . who know too much to sacrifice

good sense to a syllogism." Ibid., 32.

10

same words) for at least twenty-five years, from an 1880 review of

Langdell's contracts book to his 1905 dissent in Lochner, in which

he declared that "[g]eneral propositions do not decide concrete

cases.

The decision will depend on a judgment or intuition more subtle

than any articulate major premise."8

The anti-logical thesis is of course, also a centerpiece of The Path

of the Law (hereinafter Path).9

Holmes’s Anti-Logic Within the Larger Structure of Path of

the Law: Path's Four Jurisprudential Theses

Path's Four Main Jurisprudential Theses

To understand the content of Holmes’s anti-logic thesis in Path, it

will be helpful to locate it among the other major theses that make

up the essay.

Holmes was not a careful systematic jurisprudential thinker,

although he certainly had many flashes of brilliant jurisprudential

insight, both with regard to relatively narrow doctrinal issues and

with regard to more abstract and traditional issues of the sort

addressed by legal positivists and natural lawyers.

Despite Holmes’s lack of systemic attentiveness, Path can

profitably be read and examined for its insights into systemic

jurisprudence.

Path advances at least four major theses, all of which concern one

overarching topic: the best explanation of legal institutions,

doctrines, and reasoning. The four theses are:

8

Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45, 76 (1905). That this is the same theme as

"law is not logic but experience" is revealed by comparing it to Holmes’s

second explicit reference to logic and experience in the chapter on void

contracts in The Common Law. There, he asserts that the "distinctions of law

are founded on experience, not on logic." Holmes, The Common Law, 244.

9

Oliver W. Holmes, "The Path of the Law," in Collected Legal Papers (New

York: Harcourt, Brace and Howe, 1920), 167.

11

(1) Prediction Thesis. Law (at least, the law from the

point of view of a lawyer) is a prediction of the decisions

courts will make, backed by the use public force.

(2) Separation Thesis. Legal norms (rules, doctrines,

principles, etc.) are not identical with moral norms, and

their conflation has caused much confusion in the study of

actual legal systems.

(3) Anti-Logic Thesis. The law of a living legal system,

such as that in the U.S., cannot be adequately explained as

an axiomatic deductive system, in large part because there

is inevitably a significant role played by the "inarticulate"

in a judge's discernment and application of the law.

(Note that Holmes offers the (in)famous "bad man" as a

heuristic device to illustrate and argue for theses 1, 2, and

3.)

(4) Rational Reform Thesis. It is (a) possible and (b)

normatively desirable to effect rational reform in the law –

reform that is both properly attentive to and properly

critical of history and tradition.

"Anti-logic" Thesis and the "Fallacy of Logical Form"

After advancing and illustrating the Separation Thesis, Holmes

turns to the second of his two "principles for the proper

understanding of law," a principle to which he refers as "the

fallacy of logical form."10

According to Holmes, the "fallacy" is "the notion that the only

force at work in the development of the law is logic."

This argument is of central concern and I shall consider it in detail

below.

Five Senses of 'Logic' in Path

There is much wisdom and insight in the four theses Holmes

proffers, but along the Path there are also some crucial missteps.

10

Ibid., 184.

12

Among them, in my view, is Holmes’s analysis of the role of

"logic"11 in legal reasoning, doctrine, and institutions.

That analysis comes in his treatment of the second of what he

refers to as two "first principles for the study of this body of

dogma or systematized prediction which we call the law,"12 which

he also calls "two pitfalls" that "lie perilously close to the narrow

path of legal doctrine"13 and two "fallacies."

The first "first principle" is the Separation Thesis (the associated

"fallacy," apparently, is failure to recognize its truth).

The second is the "fallacy of logical form" -- "the notion that the

only force at work in the development of the law is logic."14

To assess the cogency of Holmes arguments about this "fallacy,"

we must first discern what exactly Holmes meant in speaking of

"logic" and "logical form."

This is no small task, since Holmes used the term 'logic' in the

essay in several rather different senses without being defining and

explaining which sense of the term he had in mind at different

points.15 This lack of systemic care is important. The anti-logical

11

I follow the standard philosophical convention of using single quotation

marks to mention words, and double quotation marks to quote a speaker's (or

group of speakers') use of a term. (Thus, logic is the systematic study of

rational inference patterns; 'logic' is a five letter word; a good deal of talk about

"logic" in American legal academia is misguided.)

12

Holmes, "The Path of the Law," 169.

13

Ibid., 178.

14

Ibid., 180. The analysis of the "fallacy of logical form" takes up about five

pages, about 14% of the total pages of the essay. Ibid., 180-84. This is roughly

equal to the space Holmes devotes to the prediction thesis (pages 168-73) and

to the separation thesis (pages 173-79). Of course discussions of these theses

overlap substantially, so it is hard (and unnecessary) to fashion an accurate

measurement of space Holmes devoted to each. I offer the rough calculation

only because it is worth noting that Holmes devotes nearly 50% of the essay to

arguing the possibility and desirability of rational reform and of sketching a

program therefor.

15

Holmes was, in many ways, a master of language, as witness the terse

and powerful aperus that have earned him that reputation. But on a

broader scale his language is full of pitfalls. The meaning of the most

central concepts in his writings, such as "philosophy," "principles,"

"logic," and "experience" would have to be clearly defined from within

Holmes’s own argument before an attempt to explicate his ideas in a

more coherent and consistent way could possibly succeed.

13

thesis has such a misleading but powerful impact on the thinking

of generations of law students, lawyers, judges, and scholars about

the ways in which it is both possible and normatively desirable to

recognize and promote the life of articulate reason in legal

decision making.16 Obviously Holmes did not explain his

understanding of logic in legal decision making only in Path;

rather, the discussion in Path reflects a view that Holmes

repeatedly articulated, and it will be helpful occasionally to repair

to passages in other works to help discern his various meanings of

'logic'.

In Path, Holmes used the term 'logic' in at least five significantly

different senses. What he said about "logic" is true of only some

of the varied referents for that term. He thus slides quite close to a

logical "fallacy" of his own (namely, equivocation). The five uses

are these:

(i)

'Logic' as one of a set of roughly synonymous terms,

including 'sensible,' 'reasonable,' 'warranted,' 'advisable.’

For example, “this really was giving up the requirement of

a trespass, and it would have been more logical, as well as

truer to the present object of the law, to abandon the

requirement altogether";17 "there are some cases in which a

logical justification can be found for speaking of civil

liabilities as imposing duties in an intelligible sense."18

(ii)

"Logic" as syllogistic inference (or some other type of

deductive inference). For example, "there is a concealed,

half conscious battle on the question of legislative policy,

and if any one thinks that it can be settled only

deductively, or once and for all, I only can say that I think

he is theoretically wrong."19

Mathias Reimann, "The Common Law and German Legal Science," in The

Legacy of Oliver Wendell Holmes, ed. Robert Gordon, (Stanford: Stanford

University Press, 1992), 146.

16

See the discussion below in Section Error! Reference source not

found..Error! Reference source not found..

17

Holmes, "The Path of the Law," 188.

18

Ibid., 175.

19

Ibid., 182-83. Although the interpretive evidence for it is slightly indirect,

Holmes does use 'logic' in Path in sense (ii). At the start of page 180, Holmes

introduces the concept of a "fallacy" in the "notion that the only force at work in

the development of the law is logic." (Later, at page 184, he refers to this

fallacy by the phrase "the fallacy of logical form.") Further down the page, in

14

(iii)

"Logic" as a formal deductive system, with axioms, rules

of inference, and theorems, as in geometry. For example,

"the danger of which I speak is . . . the notion that a given

[legal] system, ours for instance, can be worked out like

mathematics from some general axioms of conduct."20

(iv)

"Logic" as a rationally discernible pattern of cause and

effect. For example, "The condition of our thinking about

the universe is that it is capable of being thought about

rationally, or, in other words, that every part of it is effect

and cause in the same sense in which those parts are with

which we are most familiar. So in the broadest sense it is

true that the law is a logical development, like everything

else."21

(v)

"Logic" as a set of argument types, individually invariant

but distinct from one another. For example, "The training

of lawyers is a training in logic. The processes of analogy,

discrimination, and deduction are those in which they are

most at home. The language of judicial decision is the

language of logic. And the logical method and form flatter

that longing for certainty and for repose which is in every

human mind."22

Query: which Sense of 'Logic' is an appropriate target for a

claim of "fallacy" (the "Fallacy of Logical Form")?

what is clearly an explication of the "fallacious" view of "logic," he refers to the

mistaken view that

a given [legal] system . . . can be worked out like mathematics from

some general axioms of conduct. . . . So judicial dissent often is

blamed, as if it meant simply that one side or the other were not doing

their sums right, and, if they would take more trouble, agreement

inevitably would come.

Ibid., 180 (emphasis added). The salient feature in Holmes simile – legal

reasoning is mistakenly thought to be "like mathematics" – is that mathematics

(and "doing sums") is a deductive process. Thus, I take Holmes’s reference to

deduction at the end of page 180 to be a exegesis of his use of 'logic' at the start

of that page, and in that way he uses 'logic' in sense (i). Ibid.

20

Ibid.

21

Ibid.

22

Ibid., 181.

15

Senses (i) and (ii) – Unproblematic

Use (i) is a common, non-technical use of 'logic' and plays no

troublesome role in Holmes’s anti-logic. Nor does use (ii) present

any real problem. Deduction is of course one type of "logical"

inference (only one among several, as I shall discuss in greater

detail below), and it would surely be a serious jurisprudential

mistake to believe that "the only force at work in the development

of law" is deductive logic. (Pace Holmes, it is difficult to find

theorists who endorse this belief, and Langdell is pretty clearly not

among them – again, more on this later.) What Holmes intends to

label the "fallacy of logical form" is what he takes to be a

particular jurisprudential view about deduction – namely, the view

that an actual legal system can be formalized in a way that allows

deductive inference of results in particular cases.23 Thus,

Holmes’s real target is not deduction per se but some view –

exactly what view we shall have to consider – about the role that

deduction either does actually play in legal argument (a

descriptive claim), or can possibly play in legal argument (a

conceptual claim), or should play in legal argument (a conceptual

and normative claim). The problems come with senses (iii) and

(iv).

Senses (iii) and (iv) – Very Problematic

It might seem that the target of Holmes’s anti-logic is

sense (iii) of 'logic' – more precisely, the view that actual legal

systems are deductively axiomatizable. But here the assertions

that comprise Holmes’s anti-logic become problematically

unclear. Holmes concedes that the proposition "the only force at

work in the development of the law is logic" is true "in the

broadest sense" (broad along what metric, one wonders) for sense

(iv) of 'logic'.24 This proposition is true, Holmes seems to believe,

by virtue of the rather Kantian view that "the postulate on which

we think about the universe is that there is a fixed quantitative

relation between every phenomenon and its antecedents and

consequents."25 As Holmes also seems to recognize, this

23

See text at note ***.

See Holmes, "The Path of the Law," 180.

25

Ibid. We know that Holmes admired Kant, at least in part, for at the end of

Path Kant is a central part of his epideictic tribute to the power of the intellect:

"To an imagination of any scope the most far-reaching form of power is not

money, it is the command of ideas. . . . Read the works of the great German

24

16

concession is a significant threat to the coherence of his antilogical and prediction theses. To see why, note that the prediction

thesis relies, at least implicitly, on the idea that judicial behavior,

like other motions and behaviors of the universe (whether

products of the intentional mind or not – Holmes does not appear

to distinguish the intentional from the purely physical), has a

rationally discernible causal structure.26 The whole idea of

"prophesying" the law seems to rely on the assumption that, in

discerning the causal structure of judicial behavior, the lawyer or

judge must examine examples of judicial behavior encountered in

experience and recorded in case reports, generalize inductively,

and predict, "prophesy," on the basis of deduction ('logic' in sense

(ii)). Thus if 'logic' is used in sense (iv), Holmes’s own prediction

thesis would be an instance of the "fallacy of logical form" unless

he can distinguish this use from a different use of 'logic' by other

theorists who, in Holmes’s view, really did commit the "fallacy."

Does he distinguish his thesis successfully?

I think not. He does tell us that the "danger of which I

speak is not the admission that principles governing other

phenomena also govern the law, but the notion that a given [legal]

system, ours for instance, can be worked out like mathematics

from some general axioms of conduct."27 That is, those who

commit the fallacy of logical form, unlike Holmesian predictors,

think that the law is or could be deductively axiomatized – sense

(iii) of 'logic'. But this brings up a tricky issue for the anti-logic

thesis. As many scholars have observed, Langdell was a chief

target for Holmes’s anti-logic.28 It is also well remarked that

jurists, and see how much more the world is governed to-day by Kant than by

Bonaparte." Ibid., 201-02. Reimann argues that Kant, in the very influence he

exercised over the "great German jurists," was at least the superficial target of

Holmes anti-logical thesis in The Common Law. His real target, suggests

Reimann, was Langdell, but Holmes the mere HLS lecturer could not, for

political reasons, directly attack the dean of Harvard Law School, where

Holmes might like a permanent job. Reimann also points out that Langdell's

view of the role of logic in law was quite different from that of many of the

"great German jurists," and that the views of at least one of them, von Savigny,

were very consonant with Holmes’s own views, though Holmes never conceded

the point. See Reimann, "German Legal Science," 146.

26

See text at note ***.

27

Holmes, "The Path of the Law," 180.

28

See Grey, "Holmes and Legal Pragmatism," 818. In correspondence with

Pollock, Holmes said of Langdell's book on contracts:

17

Langdell, in the brief passages in which he discusses the matter

(probably too brief to get a clear picture of his view), seemed to

think of the system of legal concepts as one that was generated by

means of inductive generalization from decided cases, rather than

from some a priori axiomatic structure, and only later applied

deductively.29 Langdell, like Holmes, saw a crucial role for logic

in sense (iv) in the "legal scientist's" discernment of legal rules

and principles. Langdell also saw a crucial role for the subsequent

use of deductive inference (logic in sense (ii)), when the

inductively discovered30 rules and principles were later applied to

individual cases; surely Holmes’s prediction thesis sees an

important role for deductive inference working on the rules and

principles discovered from experience. In this way, Langdell's

conception of the role of "logic" was much closer to Holmes’s

than Holmes acknowledged.

Despite these similarities, real differences of opinion about

the role of logic in legal argument seemed to remain between

Holmes and Langdell. Langdell was far more sanguine than

Holmes about the possibility of organizing the inductivelygenerated rules and principles into a coherent conceptual order

that could later be applied to individual cases apodictically. In the

helpful terms Tom Grey brought to the analysis of "Langdell's

orthodoxy," Langdell may have believed, along with other "legal

scientists" of his day, that empirically (and inductively) generated

A more misspent piece of marvelous ingenuity I never read, yet it is

most suggestive and instructive. I have referred to Langdell several

times in dealing with contracts because to my mind he represents the

powers of darkness. He is all for logic and hates any reference to

anything outside of it, and his explanations and reconciliations of the

cases would have astonished the judges who decided them. But he is a

noble old swell whose knowledge, ability and idealist devotion to his

work I revere and love.

Oliver W. Holmes to Frederick Pollock, Boston, 10 April 1881, HolmesPollock Letters: The Correspondence of Mr. Justice Holmes and Sir Frederick

Pollock, 1874-1932, ed. Mark DeWolfe Howe (Cambridge: Belknap Press,

1961), 16-17.

29

See M. H. Hoeflich, "Law and Geometry: Legal Science from Leibniz to

Langdell," American Journal of Legal History 30 (1986): 95. See Reimann,

"German Legal Science," 108-110; Grey, "Langdell's Orthodoxy," 29-30;

Anthony J. Sebok, "Misunderstanding Positivism," Michigan Law Review 93

(1995): 2054.

30

Actually, the inductions that both Holmes and Langdell contemplated relied

on an initial abductive inference as well, as do all inductive inferences.

18

legal rules and principles could in fact be organized into a system

that was "complete" (i.e., such as to provide one right answer to

every case), "conceptually ordered" (i.e., consisting of lower level

rules that could be derived from a smaller set of higher order

principles that were themselves coherent), and "formal" (i.e., such

as to provide apodictic certainty for individual legal decisions).31

Although Holmes himself aspired in much of his work to render

areas of law into conceptually ordered systems, he was also quite

skeptical of the ability of any "legal scientist," himself included,

actually to organize legal rules and principles so as to allow for

one right and certain resolution – such as deduction could in

theory provide – of every case.32 For Holmes, blind, "inarticulate"

and irrational forces were too powerfully present in legal

decisionmaking for Langdell's conceptualistic goals to be

realizable:

[T]he logical method and form flatter that longing for

certainty and for repose which is in every human mind.

But certainty generally is an illusion, and repose is not the

destiny of man. Behind the logical form lies a judgment as

to the relative worth and importance of competing

legislative grounds, often an inarticulate and unconscious

judgment, it is true, and yet the very root and nerve of the

whole proceeding.33

This is a real disagreement, but if it is this view that Holmes was

targeting as the "fallacy of logical form," then the fit between the

Langdellian ontology and epistemology of law (inductive

discovery, conceptual ordering, deductive application) and the

fallacy of logical form Holmes is tenuous at best. Again, in

Holmes’s terms, the "fallacy" is "the notion that the only force at

work in the development of law is logic."34 If 'logic' in this

proposition is being used in either sense (ii) (deductive inference)

or sense (iii) (a deductive system), then that proposition seems not

to describe Langdell's view at all; as noted above, Langdell

accorded a vital role to both inductive inference (close kin to

'logic' in Holmes’s sense (iv) – rationally discernible causal) and

31

32

33

34

See Grey, "Langdell's Orthodoxy," 6-11.

See text at note ***.

Holmes, "The Path of the Law," 181.

Ibid., 180 (emphasis added).

19

to deductive inference ('logic' in sense (ii)), operating in a system

conceptually ordered by the "legal scientist" ('logic' in sense (iii)).

But Holmes conceded that in sense (iv) of 'logic', which Langdell

thought a vital part of legal analysis, logic was a vital force in the

development of law (indeed, he even suggested, "the only force,"

albeit only "in the broadest sense"35). In sum, though there was

genuine disagreement between Holmes and Langdell about the

role of deductive logic in legal reasoning, the disagreement was

not nearly as great as Holmes made it out, in part because Holmes

mischaracterized the complexity of Langdell's own views about

the role of different modes of logical inference in legal argument.

(I discuss those different modes in some detail in the next section.)

**Sense (v) – Most Promising

This brings me to a final point. Holmes seems unclear about what

he himself understood to be within the scope of the kind of "logic"

involved in the "fallacy of logical form." The "fallacy of logical

form" seems to be the view that law can be organized into an

axiomatic system in such a way as to allow for apodictic

resolution of individual cases. But at a crucial point in the antilogic section of the paper, Holmes speaks as if it is neither solely

deduction ('logic' in sense (ii)) nor solely a deductive system (logic

in sense (iii)) that he has targeted, but rather something much

more inclusive, namely, 'logic' in sense (v):

[J]udicial dissent is often blamed, as if it meant simply that

one side or the other were not doing their sums right, and,

if they would take more trouble, agreement inevitably

would come.

This mode of thinking is entirely natural. The training of

lawyers is a training in logic. The processes of analogy,

discrimination, and deduction are those in which they are

most at home. The language of judicial decision is mainly

the language of logic. And the logical method and form

flatter that longing for certainty and repose which is in

every human mind.36

35

36

Ibid.

Ibid., 181.

20

Now, it seems, the fallacious view about the possible role of

"logic" in legal argument that Holmes is challenging embraces not

only "deduction" but also "the processes of analogy and

discrimination" – i.e., disanalogical argument! A critique of the

role of "logic" in legal reasoning that is this inclusive is surely a

far cry from the narrower and much more plausible view that law

cannot be organized into an axiomatic system that is deductively

applicable in every case. One has to be not just skeptical, but

skeptical to an implausible extreme, to deny that logic in the broad

sense of a patterned form of inference (including deduction and

analogy) plays a vital role "in the development of law." And if the

response on behalf of Holmes is that he is not critiquing the view

that "logic" plays a vital role in the development of law, but is

instead critiquing the literal belief that "the only force at work in

the development of law is logic," well, we must ask who ever

believed that logic, in any sense, was the only force at work in the

development of law? If the proposition Holmes uses to describe

the "fallacy of logical form"37 is taken literally, it seems no one,

including the most "formalist" and deductivist of the legal

scientists – German, British, or American – could have believed or

endorsed that. The ball is in Holmes’s court: if he really means it

literally, he must show us that he is not attacking a straw theory.

Ironically, perhaps, it is this last of the five conceptions of logic

that is the most promising for a deep and cogent explanation of the

role of different modes of logical inference in legal argument. As

so often, even when Holmes is misguided and somewhat

confused, his suggestions are fertile. In Part II of this paper I take

up that "suggestion" and explore the role, not just of "logic" in the

narrow sense of deduction, but in the broad sense of patterned

inference. Marking the different patterns of logical inference that

can be used in legal argument, that are used in legal argument,

and that should be used in legal argument comprises the work of

an ongoing intellectual enterprise. I call that enterprise the

jurisprudence of logical form.

Dewey's defense of Holmes' general anti-deductivism

The most challenging claim, and the most suggestive about his

view of the role of defeasibility and deduction in judicial legal

37

I have quoted that proposition several times. See, for example, the text at

note 14.

21

argument, comes in this following passage in the Dewey article,

Logical Method and Law:

Take the case of Socrates being tried before the Athenian

citizens, and the thinking which had to be done to reach a

decision. Certainly the issue was not whether Socrates

was mortal; the point was whether this mortality would or

should occur at a specified date and in a specified way.

Now that is just what does not and cannot follow from

a general principle or a major premise. Again to quote

Justice Holmes, "General propositions do not decide

concrete cases." No concrete proposition, that is to say

one with material dated in time and placed in space,

follows from any general statements or from any

connection between them. [Logical Method and Law, p.

22.5 (emphasis added)]

Does this assertion have direct implications for structural enthymemicity,

practical enthymemicity, or both? (See definitions above.)

The Scope of Dewey's claim

Dewey's assertion raises at least two questions of interpretation.

First, what is the scope of Dewey's claim? Does he intend to limit

the scope of his claim to the domain of legal reasoning (including

legal reasoning in 5th century Athens and in early 20th century

America – or maybe including legal reasoning everywhere and

everywhen?) but not extend the claim to reasoning in other

domains, such as the domain of moral reasoning, instrumental

("prudential") reasoning, or reasoning in the empirical sciences?

Second, what exactly is the meaning of the claim, or, more

precisely, what does Dewey intend to be the referent of 'them' in

his assertion that "No concrete proposition, that is to say one with

material dated in time and placed in space, follows from any

general statements or from any connection between them"? Does

'them' refer to any connection between general propositions, or

does it refer to any connection between general and concrete

propositions?

Did Dewey intend his claim to be limited to legal reasoning? To legal and

moral reasoning? To all types of practical reasoning?

22

It seems likely that Dewey does not intend to limit his claim to

legal reasoning, nor even to the more general category of practical

reasoning (practical reasoning is reasoning about what one ought

to do -- this includes as "sub domains," as species within its genus,

moral reasoning, legal reasoning, and instrumental-prudential

reasoning

See for example Dewey's characterization of "'practical'

reasonings" as "reasonings leading up to decision as to

what is to be done," Logical Method and Law, 10 Cornell

L. Q. at 18.9

Also compare Joseph Raz' related distinction of "practical"

and "theoretical" authorities, Raz, Authority, Law, and

Morality, at 195.9). But the views Dewey advances in this

article are striking in that he seems committed to absorbing

all theoretical reasoning (reasoning about what one ought

to believe) into the domain of practical reasoning.

Some evidence for this comes in his assertion, quoted above,

quoting Holmes and referring to Socrates. Dewey's reference to

Socrates' execution surely is intended to evoke the syllogism so

familiar (in Dewey's day too, one speculates) to students of

traditional syllogistic logic:

All men are mortal

Socrates is a man

Therefore, Socrates is mortal

And his deliberate invocation of that non-legal deductive

syllogism when explaining his claim about general and concrete

propositions suggests that he believes that his thesis is not limited

to legal argument.

Additional evidence is found later in the article, where he

explicitly considers the scope of his inquiry into “logical method,”

and defines ‘logical theory’ as

an account of the procedures followed in reaching

decisions . . . in which subsequent experience shows that

they were the best [procedures] which could have been

23

used under the conditions. [Logical Method and Law, 10

Cornell L. Q. at 17-18.]

In like vein, he asserts:

It will be said that [the foregoing] definition [of ‘logical

theory’] . . . , in confining logical procedure to practical

matters, fails to take even a glance at those cases in which

true logical method is best exemplified: namely, scientific,

especially mathematical, subjects.” [Logical Method and

Law, 10 Cornell L. Q. at 18 (emphases added)]

Note the dialectic here: Dewey He considers one possible

challenge to this conception of "logic":

Challenge: The scope of his analysis of "logic" is "logical

method in legal reasoning and legal decision," and in those

cases the legal reasoner is engaged in practical reasoning,

the type of reasoning that confronts "the necessity of

settling upon a course of action to be pursued." [Logical

Method and Law, 10 Cornell L. Q. at 18.3]

So perhaps not all "logic" is assimilable to practical

reasoning, and Dewey is claiming to offer a philosophical

explanation only of the species of practical logical

reasoning and not of the genus of all logical reasoning,

including theoretical reasoning?

Dialectic: Dewey's reply: No.

Having offered that suggestion, Dewey chooses not to rest

his analysis of "logic" on that answer, which he

characterizes as "partial" and "ad hoc." [Logical Method

and Law, 10 Cornell L. Q. at 18.3.]

Having acknowledged that others might regard his

definition of logical theory as ill-suited to explain

reasoning in "scientific and mathematical subjects," he still

suggests that even the mathematician’s “logical

procedures” can be assimilated to practical reasoning,

since “every thinker, as an investigator, mathematician or

24

physicist as well as ‘practical man,’ think in order to

determine his decisions and conduct—his conduct as a

specialized agent working in a carefully delimited field.”

[Logical Method and Law, 10 Cornell L. Q. at 18-19]

After offering these preliminary remarks, Dewey considers

what he clearly understood was then – and is still today –

the far more dominant explication of the concept of logic ,

namely, "an affair of propositions which constitute . . .

with a view to the utmost generality and consistency of

propositions.” [Logical Method and Law, 10 Cornell L. Q.

at 19].

But again, while acknowledging some utility for this

conception of “logic,” he seems to suggest that logic so

conceived is always only a means, not an end in itself, a

“means of improving, facilitating, clarifying the inquiry

that leads up to concrete decisions.” [Logical Method and

Law, 10 Cornell L. Q. at 19].

Dewey also invokes the case of legal reasoning to

advance an argument whose conclusion seems to be

that logic is always “ultimately an empirical and

concrete discipline” (Logical Method and Law, 10

Cornell L. Q. at 19), and that “logic must be . . . a logic

relative to consequences rather than antecedents, a

logic of prediction of possibilities rather than a

deduction of certainties.” (Logical Method and Law, 10

Cornell L. Q. at 26).

Later in his argument, he asserts the more general proposition that

and “logic is really a theory about empirical phenomena, subject

to growth and improvement like any other empirical discipline.”

[Logical Method and Law, 10 Cornell L. Q. at 27 (emphasis

added)].

In this striking claim Dewey seems aligned with the extreme

empiricist view advanced, for example, by John Stuart Mill:

[T]he foundation of all sciences, even deductive or

demonstrative sciences, is Induction; . . . every step in the

25

ratiocinations even of geometry is an act of induction; . . .a

train of reasoning is but bring many inductions to bear

upon the same subject of inquiry, and drawing a case

within one induction by means of another. [J. S. Mill, A

System of Logic 147 (8th ed. 1959).38]

Is this view of deductive logic -- assimilating it either to practical

reasoning (as Dewey suggests at several points) or to empirical

reasoning (as he suggests at other points) convincing?

Here are some reasons to doubt his claim. Dewey seems to trade

on the vagueness of the idea of the kind of "concrete decision" that

is a mathematician or logician must make when attempting to

offer a formal mathematical or logical proof.

If Dewey means to include within the scope of “concrete

decisions" Andrew Wiles’ “decision” to offer the proof he offered

of Fermat’s last theorem, then maybe Dewey is right in some

sense. But something seems off here, for that kind of “decision”

does not seem to support Dewey's contention that “logic is

ultimately an empirical and concrete discipline.”

38

Compare also the striking and intriguiging assertion by Chalres Sanders

Peirce, one of America's greatest formal logicians, also, like Holmes and Felix

Cohen, a theorist in the "pragmatist" tradition:

It may seem strange that I should put forward three sentiments,

namely, interest in an indefinite community, recognition of the

possibility of this interest being made supreme, and hope in the

unlimited continuance of intellectual activity, as indispensable

requirements of logic. Yet, when we consider that logic depends on a

mere struggle to escape doubt, which, as it terminates in action, must

begin in emotion, and that, furthermore, the only cause of our planting

ourselves on reason is that other methods of escaping doubt fail on

account of the social impulse, why should we wonder to find social

sentiment presupposed in reasoning? As for the other two sentiments

which I find necessary, they are so only as supports and accessories of

that. It interests me to notice that these three sentiments seem to be

pretty much the same as that famous trio of Charity, Faith, and Hope,

which in the estimation of St. Paul, are the finest and greatest of

spiritual gifts. Neither Old nor New Testament is a textbook of the

logic of science, but the latter is certainly the highest existing authority

in regard to the dispositions of heart which a man ought to have.

[Charles S. Peirce, Three Logical Sentiments [CP 2.655]

26

What Dewey’s (and Mill's) hyper-empiricism fails to account for

is the distinction between an a priori and a posteriori discipline.

Empirical support is need for empirical disciples but empirical

support does not seem needed for a priori disciplines. Indeed it's

hard to imagine what kind of empirical support one could get for

such logical inference rules such as modus ponens and universal

instantiation.

However convincingly (or not) Dewey does seem to endorse the

thesis that all "logical" reasoning, even reasoning in mathematics,

is a species of practical reasoning and a species of empirical

reasoning.

This leads us to our next interpretive challenge in understanding

Dewey's explanation of legal argument: when he says that "[n]o

concrete proposition, that is to say one with material dated in time

and placed in space, follows from any general statements or from

any connection between them," what is the referent of 'them'?

Does he intend "them" to refer to general and concrete

propositions, or instead only to concrete propositions?

Is Dewey's claim coherent? Immediate and fairly straightforward

counter-example?

Premise:

Everything is identical to itself at all times

and in all places.

Conclusion: Socrates was identical to himself in Athens

in 399 B.C.

This argument has the logical form of what logicians refer to as

the inference rule of “universal instantiation”

(x) Fx

Fa

If so, is Dewey committed to denying that the conclusion of this

argument follows deductively from its premise?

It's hard to imagine a more general proposition than the

proposition asserted in the premise of this argument. And the

27

conclusion also seems to be a paradigm instance of a "concrete

proposition" in Dewey's sense.

Rule skepticism and induction: Holmes, Dewey, Cohen

The basic patterns of inductive inference:

generalization and inductive specification

inductive

Recall that in an inductive argument, the truth of the premises

cannot guarantee the truth of the conclusion, but when they are

well chosen, their truth can warrant belief in the truth of the

conclusion to some degree of probability. There are two main

varieties of inductive inference: inductive generalization and

inductive specification.

Inductive generalization

Inductive generalization involves generalizing from particular

instances. The premises of this type of argument report features of

the particulars, and its conclusion states a probabilistic

generalization that is inferred from those particulars. In the notes

below we'll use two examples to illustrate the form of inductive

generalization. One is the Knapp judge's analysis of logical

relevance in the case he was deciding, the other is a simplified

example from empirical science (induction is one of the

foundations of all empirical scientific reasoning).

Where

'1 . . . n'

instances

stands for a set of individual

' '

stands for one property that

the individuals 1 . . . n

have been noted to possess

''

stands for another property

the individuals 1 . . . n

have been noted to possess,

the pattern of inductive

generalization is:

28

(1 )

1 is both and (i.e., has both characteristics,

and )

[e.g., Person A made a factual assertion and

Person A spoke truly.]

[e.g., Bird A was a raven and Bird A was

black.]

(2 )

2 is both and

[e.g., Person B made a factual assertion and

Person B spoke truly.]

[e.g., Bird B was a raven and Bird B was

black.]

(3 )

3 is both and

[e.g., Person C made a factual assertion and

Person C spoke truly.]

[e.g., Bird C was a raven and Bird C was

black.]

.

.

.

(n)

n is both and

[e.g., Person N made a factual assertion and

Person N spoke truly.]

[e.g., Bird N was a raven and Bird N was

black.]

(n+1) There were [few or no] observed instances of an

that was and also was not-

[e.g., There were few persons who made a

factual assertion and did not speak truly -Knapp: "even in the greatest liars, . . .

where they lie once they speak truth 100

times."]

29

[e.g. No ravens were observed to be nonblack]

h: [Probably] [All or Most] 's are

[e.g., Knapp: Probably, most persons who

make factual assertions are persons who

speak truly.]

[e.g. Probably, all ravens are black.]

Note that inductive arguments are arguments about evidence and

the hypotheses the evidence is said to support. Thus, the premises

of an inductive argument are evidentiary propositions (the " " in

our - h schema) and the conclusion is a hypothesis that the

evidence is offered to support the "h" in our - h schema.

Inductive specification

The other type of inductive inference is inductive specification.

Instead of reaching a conclusion about a class of individuals, an

inductive specification offers a conclusion about one individual,

based on a generalization about the classes to which that

individual belongs. Again, we illustrate the form of this argument

by reference to the two examples offered above:

In the Knapp example, the inductive specification is the

argument that a great many persons (Knapp endorses the

claim that the ratio is 100 to 1!) who made factual

assertions spoke truly, therefore, some individual person D

who made a factual assertion (or perhaps the next

individual person who will makes a factual assertion -- see

the note in the following paragraph) is also likely to have

spoken truly (or likely will speak truly).

In the raven example, the inductive specification is the

argument that a great many (actually, in this example, all)

ravens were black, therefore, some individual raven was

black (or perhaps the next observed individual raven will

be black -- again, see the note in the following paragraph).

30

Note that inductive analogies are a basic form of

argument for making predictions based on

empirical evidence -- predictions, for example,

about the next person we encounter who will make

a factual assertion, or the next raven we will see.

The abstract form of the argument is this:

(1 through n ) 1 through n have all been both and

(i.e., has both characteristics, and ).

[e.g., Person A through Person N all made a

factual assertion and spoke truly.]

[e.g., Bird A through Bird N all were ravens

and black.]

(n+1) There were few observed instances of an that was

and also was not-

[e.g., There were few Persons who made a

factual assertion and did not speak truly.]

[e.g. No ravens were observed to be nonblack.]

Therefore, h: Some individual n+1 probably has both

and .

Some Person (perhaps some person we

encounter in the future) who makes a

factual assertion probably spoke (or

probably will speak) truly.

Some Bird (perhaps some bird we

encounter in the future) who is a raven

probably is black.

31

Characteristic common to

specification

inductive generalization and

inductive

In order for to assess how convincing an inductive inference is,

one must assess the premises or conclusion according to several

criteria (cf. Steven Barker, Elements of Logic (5th ed. p. 187)):

the number of observed instances

the degree of shared characteristics among the

identified characteristics

the degree of unshared characteristics among the

identified characteristics

the logical strength of the conclusion ("all," "some,"

"probably," "very likely" etc.)

the explanatory relations among the identified

characteristics

Note that probabilistic judgments ("probably," "almost certainly,"

"more likely than not," etc.) are always relative to some evidence.

See Barker, op. cit. p. 184: "[P]robability when understood as

rational credibility is a relative matter . . . . The very same

conjecture takes on different degrees of probability relative to

different amounts of evidence."

Note also that there is (or should be) a close relation between our

judgment regarding how probable we think a conclusion is relative

to the evidence offered in the inductive argument and the logical

strength of the conclusion (e.g., the conclusion "All individuals

that have property have property " is logically stronger than

the conclusion "Some individuals that have property have

property "; in the examples above, the conclusion in raven

induction was logically stronger than the conclusion in the Knapp

induction).

Although it may be counter-intuitive, note that the greater the

logical strength of the conclusion of an inductive argument, the

lower is the probability of that conclusion relative to the evidence

stated in the argument's premises. (Logician Stephen Barker

makes this point as follows: "The more sweeping the

generalization that we seek to establish, the less is its probability

relative to our evidence." (see Barker op. cit. p. 187)). Do you see

why this is true?

32

Some uses of inductive inference in legal argument

Using induction to find the law (the lawyer) -- Holmes' bad

man

"Take the fundamental question, What constitutes the law?

You will find some text writers telling you that it is

something different from what is decided by the courts of

Massachusetts or England, that it is a system of reason,

that it is a deduction from principles of ethics or admitted

axioms or what not, which may or may not coincide with

the decisions. But if we take the view of our friend the bad

man we shall find that he does not care two straws for the

axioms or deductions, but that he does want to know what

the Massachusetts or English courts are likely to do in fact.

I am much of his mind. The prophecies of what the courts

will do in fact, and nothing more pretentious, are what I

mean by the law." [The Path of the Law]

Using induction to make the law (the lawyer, the judge, the

legislator, the administrative agent, the constitutional

adopter): Dewey on the practical, experiential, inductive

nature of "logical" method -- in law and elsewhere

"If we recur then to our introductory conception that logic

is really a theory about empirical phenomena, subject

to growth and improvement like any other empirical

discipline, we recur to it with, an added conviction:

namely, that the issue is not a purely speculative one, but

implies consequences vastly significant for practice. I

should indeed not hesitate to assert that the

sanctification of ready-made antecedent universal

principles as methods of thinking is the chief obstacle

to the kind of thinking which is the indispensable

prerequisite of steady, secure and intelligent social

reforms in general and social advance by means of law

in particular. If this be so infiltration into law of a

more experimental and flexible logic is a social as well

as an intellectual need." [Logical Method and the Law 26]

"If we trust to an experimental logic, we find that

general principles emerge as statements of generic

33

ways in which it has been found helpful to treat

concrete cases. The real force of the proposition that all

men are mortal is found in the expectancy tables of

insurance companies, which with their accompanying rates

show how it is prudent and socially useful to deal with

human mortality. The 'universal' stated in the major

premise is not outside of and antecedent to particular

cases; neither is it a selection of something found in a

variety of cases. It is an indication of a single way of

treating cases for certain purposes or consequences in

spite of their diversity." [Logical Method and the Law 22]

Question for Dewey: Is that true of 'F = MA' as well?

Using induction to find "legislative facts" – recall "Dewey's

Dream": Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 493-95

(1954)

"We come then to the question presented: Does

segregation of children in public schools solely on the

basis of race, even though the physical facilities and

other 'tangible' factors may be equal, deprive the

children of the minority group of equal educational

opportunities? We believe that it does. . . . To separate

[Negro schoolchildren] from others of similar age and

qualifications solely because of their race generates a

feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community

that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely

ever to be undone. The effect of this separation on their

educational opportunities was well stated by a finding in

the Kansas case by a court which nevertheless felt

compelled to rule against the Negro plaintiffs: 'Segregation

of white and colored children in public schools has a

detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is

greater when it has the sanction of the law; for the policy

of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting

the inferiority of the negro group. A sense of inferiority

affects the motivation of a child to learn. Segregation with

the sanction of law, therefore, has a tendency to (retard)

the educational and mental development of Negro children

and to deprive them of some of the benefits they would

receive in a racial(ly) integrated school system.' . . . .

34

Whatever may have been the extent of psychological

knowledge at the time of Plessy v. Ferguson, this

finding is amply supported by modern authority.

[FN11] Any language in Plessy v. Ferguson contrary to

this finding is rejected.

FN11. K. B. Clark, Effect of Prejudice and

Discrimination on Personality Development

(Midcentury White House Conference on Children

and Youth,

1950); Witmer and Kotinsky,

Personality in the Making (1952), c. VI; Deutscher

and Chein, The Psychological Effects of Enforced

Segregation: ASurvey of Social Science Opinion,

26 J.Psychol. 259 (1948); Chein, What are the

Psychological Effects of Segregation Under

Conditions of Equal Facilities?, 3 Int. J. Opinion

and Attitude Res. 229 (1949); Brameld,

Educational Costs, in Discrimination and National

Welfare (MacIver, ed.,1949), 44--48; Frazier, The

Negro in the United States (1949), 674--681. And

see generally Myrdal, An American Dilemma

(1944).

We conclude that in the field of public education the

doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place. Separate

educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we

hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for

whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the

segregation complained of, deprived of the equal

protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment. This disposition makes unnecessary any

discussion whether such segregation also violates the Due

Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. . . . .

Is there no deductive reasoning in legal reasoning?

Cohen's challenge in The Ethical Basis of Legal

Criticism pages 216-219 (1931)

But elementary logic teaches us that every legal decision

and every finite set of decisions can be subsumed under an

35

infinite number of different general rules, just as an infinite

number of different curves may be traced through any point or

finite collection of points. Every decision is a choice between

different rules which logically fit all past decisions but

logically dictate conflicting results in the instant case. Logic

provides the springboard but it does not guarantee the success

of any particular dive.

If the doctrine of stare decisis means anything, and one can

hardly maintain the contrary despite the infelicitous formula tions which have been given to the doctrine, the consistency

which it demands cannot be a logical consistency. The consistency in question is more akin to that quality of dough which is

necessary for the fixing of a durable shape. Decisions are

fluid

particular decision. See WAMBAUGH, STUDY OF CASES (2d ed. 1894) c. 2; Salmond,

T h e o r y o f J u d i c i a l P r e c e d e n t s (1900) 16 L. Q. REV. 376; GRAY, op. cit. supra

note 11, at § 555; BLACK, JUDICIAL PRECEDENTS (1912) 40; MORGAN, op. cit. supra

note 29, at 109-10; Goodhart, Determining the Ratio Decidendi of a Case (1930) 40

YALE L. J. 161. Logical objections to this conception are dismissed by Professor Morgan as

"hypercritical" and 'too refined for practical purposes." But Professor Oliphant, who

refuses to be deterred by such warnings (see his reply in M u t u a l i t y o f Ob l i g a tion in

Bilateral Contracts at Law (1928) 28 COL. L. REV. 997 n. 2 to Professor Williston's

charges of scholasticism, The Effect of One Void -Promise in a Bilateral Agreement

(1925) 25 COL. L. REV. 857, 869) has suggested an alternative conception that is logically

sound and practically far more useful. Rules of increasing generality, each of them linking

the given result to the given facts, spread pyramid-wise from a decision. The possibility of

alternative modes of anaylsis makes a decision the apex not of one but many such

pyramids. No one of these rules has any logical priority; courts and lawyers choose among

competing propositions on extra-logical grounds. Oliphant, A Return to Stare Decisis

(1928) 6 AM. LAW SCHOOL REV. 215, 217-18; and cf. LLEWELLYN, BRAMBLE BUSH

(1930) 61-66; Bingham, What is the Law? (1912) 11 MICH. L. REV. 1, 109, 111 n. 31.

The picture clearly suggests that the decision bears to the rules the same relation that

Professor Whitehead has traced between a point and the surfaces that would ordinarily be

said to include the point. See THE PRINCIPLES OF NATURAL KNOWLEDGE (1919) c. 8;

THE CONCEPT OF NATURE (1919) c. 4.

40 Loc. cit. supra, note 39.

36

1931]

LEGAL CRITICISM

217

until they are given "morals." It is often important to conserve with new

obeisance the morals which lawyers and laymen have read into past decisions

and in reliance upon which they have acted. We do not deny that importance

when we recognize that with equal logical justification lawyers and laymen

might have attached other morals to the old cases had their habits of legal

classification or their general social premises been different. But we do shift the

focus of our vision from a stage where social and professional prejudices wear

the terrible armor of Pure Reason to an arena where human hopes and

expectations wrestle naked for supremacy.

No doubt the doctrine of stare decisis and the argument for consistency

have a significance which is not exhausted by the social usefulness of

predictable law. Even in fields where past court decisions play a negligible

role in molding expectations, courts may be justified in looking to former

rulings for guidance. The time of judges is more limited than the boundaries of

injustice. At some risk the results of past deliberation in a case similar to the

case at bar must be accepted. But again we invite fatal confusion if we think of

this similarity as a logical rather than an ethical relation. To the cold eyes of

logic the difference between the names of the parties in the two decisions bulks

as large as the difference between care and negligence. The question before

the judge is, "Granted that there are differences between the cited precedent

and the case at bar, and assuming that the decision in the earlier case was a

desirable one, is it desirable to attach legal weight to any of the factual differences

between the instant case and the earlier case?" Obviously this is an ethical

question. Should a rich woman accused of larceny receive the same treatment as

a poor woman? Should a rich man who has accidentally injured another come

under the same obligations as a poor man? Should a group of persons, e. g., an

unincorporated labor union, be privileged to make all statements that an individual

may lawfully make? Neither the ringing hexameters of Barbara Celarent nor

the logic machine of Jevons nor the true-false patterns of Wittgenstein will

produce answers to these questions.

What then shall we think of attempts to frame practical legal issues as conflicts

between morality, common sense, history or sociology, and logic (logic playing

regularly the Satanic role) ? One hesitates to convict the foremost jurists on

the American bench of elementary logical error. It is more likely that they

have simply used the word "logic" in peculiar ways, as to which they may find

many precedents in the current logic textbooks.41

See M. R. Cohen, The Subject Matter of Formal Logic (1918) 15 JOUR.

OF PHIL. 673.

4'

37

218

YALE LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 41

Bertrand Russell has warned us :

"When it is said, for example, that the French are 'logical',