Chapter 2 - Socio

advertisement

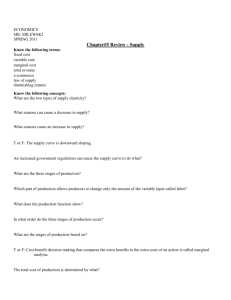

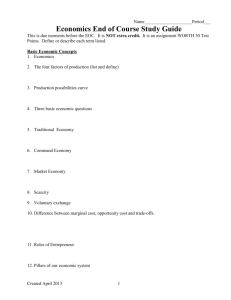

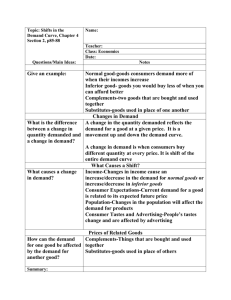

MICROECONOMICS Chapter 1 Comparative Statics Analysis Marginal Impact A Comparative Statics Analysis compares the equilibrium state of a system before a change in the exogenous variables to the equilibrium state after the change The Marginal Impact of a change in the exogenous variable is the incremental impact of the last unit of the exogenous variable on the endogenous variable. Chapter 2 Competitive Markets Market Demand Function Demand Curve Law of Demand Law of Supply Market Equilibrium Excess Supply Price Elasticity of Demand Competitive Markets are those with sellers and buyers that are small and numerous enough that they take the market price as given when they decide how much to buy and sell. The Market Demand Function tells us how the quantity of a good demanded by the sum of all consumers in the market depends on various factors. Qd = (Q,p,p0,I,…) The Demand Curve plots the aggregate quantity of a good that consumers are willing to buy at different prices, holding constant other demand drivers such as prices of other goods, consumer income, quality. Qd = Q(p) The Law of Demand states that the quantity of a good demanded decreases when the price of this good increases. The Law of Supply states that the quantity of a good offered increases when the price of this good increases. A Market Equilibrium is a price such that, at this price, the quantities demanded and supplied are the same. V=A If sellers cannot sell as much as they would like at the current price, there is Excess Supply. If there is no excess supply or excess demand, there is no pressure for prices to change and thus there is equilibrium. The Price Elasticity of Demand is the percentage change in quantity demanded brought about by a one-percent change in the price of the good. 𝜕𝑄 𝑃 𝜀 = 𝜕𝑃 ∙ 𝑄 Elastic Demand Curve Inelastic Demand Curve Unit Elastic Demand Curve When a one percent change in price leads to a greater than onepercent change in quantity demanded, the demand curve is elastic. (Q,P < -1) Demand tends to be more elastic: *the larger the number of close substitutes *the more narrowly defined the market *if the good is a luxury *the longer the time horizon When a one-percent change in price leads to a less than onepercent change in quantity demanded, the demand curve is inelastic. (0 > Q,P > -1) When a one-percent change in price leads to an exactly onepercent change in quantity demanded, the demand curve is unit elastic. (Q,P = -1) Income Elasticity of Demand Cross-price Elasticity of Demand Price Elasticity of Supply Income elasticity of demand measures how much the quantity demanded of a good responds to a change in consumers’ income. <0 : Inferior good >0 : Normal good Between 0 and 1 : Necessity >1: Luxury good 𝜕𝑌 𝐼 𝜀𝑌𝐼 = ∙ 𝜕𝐼 𝑌 The Cross-price elasticity of demand measures how much the quantity demanded of a good responds to a change in the price of another good. (complements – substitutes) Price elasticity of supply is a measure of how much the quantity supplied of a good responds to a change in the price of that good. Chapter 3 Consumer Preferences Basket Bundle Preferences are complete Preferences are transitive Preferences are monotonic Indifference Curve Indifference Set Indifference Map Marginal Rate of Substitution Utility function Quasi-linear utility functions Consumer Preferences tell us how the consumer would rank (that is, compare the desirability of) any two combinations or allotments of goods, assuming these allotments were available to the consumer at no cost. These allotments of goods are referred to as baskets or bundles. These baskets are assumed to be available for consumption at a particular time, place and under particular physical circumstances. Preferences are complete if the consumer can rank any two baskets of goods (A preferred to B; B preferred to A; or indifferent between A and B) Preferences are transitive if a consumer who prefers basket A to basket B, and basket B to basket C also prefers basket A to basket C Preferences are monotonic if a basket with more of at least one good and no less of any good is preferred to the original basket. An Indifference Curve or Indifference Set: is the set of all baskets for which the consumer is indifferent. *Negatively sloped *Convex to origin *Do not intersect *Each bundle belongs to just one IC *Cannot be ‘thick’ An Indifference Map : Illustrates a set of indifference curves for a consumer The marginal rate of substitution: is the maximum rate at which the consumer would be willing to substitute a little more of good x for a little less of good y. 𝑈𝑥 𝑥, 𝑦 𝑃𝑥 𝑀𝑅𝑆𝑥,𝑦 𝑥, 𝑦 = = 𝑈𝑦 𝑥, 𝑦 𝑃𝑦 Grafisch: helling van de raaklijn in een punt aan de indifferentiecurve. The utility function assigns a number to each basket so that more preferred baskets get a higher number than less preferred baskets. Utility is an ordinal concept: the precise magnitude of the number that the function assigns has no significance. The only thing that determines your personal trade-off between x and y is how much x you already have. U = v(x) + Ay Marginal Utility The marginal utility of a good, x, is the additional utility that the consumer gets from consuming a little more of x when the consumption of all the other goods in the consumer’s basket remain constant. 1 good : 𝑀𝑈𝑦 (𝑦) = 𝑈 ′ 𝑦 = 𝑑𝑈𝑦 𝑑𝑦 2 goods: 𝑀𝑈𝑥 (𝑥, 𝑦) = 𝑈𝑥 𝑥, 𝑦 = 𝜕𝑈𝑥,𝑦 𝜕𝑥 𝑀𝑈𝑦 (𝑥, 𝑦) = 𝑈𝑦 𝑥, 𝑦 = 𝜕𝑈𝑥,𝑦 𝜕𝑦 Chapter 4 Budget Constraint Interior Optimum Tangent Corner solution The set of baskets that the consumer may purchase given the limits of the available income. 𝑃𝑥 𝑥 + 𝑃𝑦 𝑦 = 𝐼 Interior Optimum: The optimal consumption basket is at a point where the indifference curve is just tangent to the budget line. A tangent: to a function is a straight line that has the same slope as the function. A corner solution occurs when the optimal bundle contains none of one of the goods. Chapter 5 Price consumption curve Engel curve Normal good Inferior good Income effect Substitution effect Giffen good Consumer surplus The price consumption curve for good x can be written as the quantity consumed of good x for any price of x. This is the individual’s demand curve for good x. The income consumption curve for good x also can be written as the quantity consumed of good x for any income level. This is the individual’s Engel Curve for good x. When the income consumption curve is positively sloped, the slope of the Engel Curve is positive. If the income consumption curve shows that the consumer purchases more of good x as her income rises, good x is a normal good. Equivalently, if the slope of the Engel curve is positive, the good is a normal good. If the income consumption curve shows that the consumer purchases less of good x as her income rises, good x is an inferior good. Equivalently, if the slope of the Engel curve is negative, the good is an inferior good. As the price of x falls, all else constant, purchasing power rises. This is called the income effect of a change in price. The income effect may be positive (normal good) or negative (inferior good). As the price of x falls, all else constant, good x becomes cheaper relative to good y. This change in relative prices alone causes the consumer to adjust his/ her consumption basket. This effect is called the substitution effect. The substitution effect always is negative. If a good is so inferior that the net effect of a price decrease of good x, all else constant, is a decrease in consumption of good x, good x is a Giffen good. For Giffen goods, demand does not slope down. The net economic benefit to the consumer due to a purchase (i.e. the willingness to pay of the consumer net of the actual expenditure on the good) is called consumer surplus. Network externalities Bandwagon Effect Snob Effect If one consumer's demand for a good changes with the number of other consumers who buy the good, there are network externalities. If one person's demand decreases with the number of other consumers, then the externality is positive. Increased quantity demanded when more consumers purchase If one person's demand decreases with the number of other consumers, then the externality is negative. Decreased quantity demanded when more consumers purchase Chapter 6 Production function Technology Technically efficient firm Production functions with single input The production function Q=f(L,K,…) tells us the maximum possible output that can be attained by the firm for any given quantity of inputs. Technology determines the quantity of output that is feasible to attain for a given set of inputs. A technically efficient firm is attaining the maximum possible output from its inputs Single input production functions Q=f(L) 𝑄 𝑓(𝐿) Average product 𝐴𝑃 = = 𝐿 𝐿 𝑑𝑓𝐿 ′ Production functions with multiple inputs Isoquant Returns to scale Scale Marginal Rate of Technical Substitution Technological progress Marginal product 𝑀𝑃 = 𝑓 𝐿 = 𝑑𝐿 Production functions with multiple inputs Q=f(L,K) 𝜕𝑓 𝐿, 𝐾 𝑀𝑃𝐿 𝐿, 𝐾 = = 𝑓𝐿 𝐿, 𝐾 𝜕𝐾 𝜕𝑓 𝐿, 𝐾 𝑀𝑃𝐾 𝐿, 𝐾 = = 𝑓𝐾 𝐿, 𝐾 𝜕𝐿 All combinations of L and K that yield the same output level Let Q=f(L,K) Globally increasing returns to scale ↔ for all (L,K) and for all λ>1: 𝑓(𝜆𝐿, 𝜆𝐾) > 𝜆𝑓(𝐿, 𝐾) Globally decreasing returns to scale ↔ for all (L,K) and for all λ>1: 𝑓(𝜆𝐿, 𝜆𝐾) < 𝜆𝑓(𝐿, 𝐾) Globally constant returns to scale ↔ for all (L,K) and for all λ>0: 𝑓(𝜆𝐿, 𝜆𝐾) = 𝜆𝑓(𝐿, 𝐾) By what % does output rise if all inputs are increased by 1%, starting from a given input combination: 𝜕𝑓 𝐿, 𝐾 𝐿 𝜕𝑓 𝐿, 𝐾 𝐾 𝜀𝑠𝑐𝑎𝑙𝑒 = ∙ + ∙ 𝜕𝐿 𝑓 𝐿, 𝐾 𝜕𝐾 𝑓 𝐿, 𝐾 We have increasing, decreasing or constant returns to scale for a given input combination (L,K) if 𝜀𝑠𝑐𝑎𝑙𝑒 is larger than, smaller than, or equal to 1. Marginal Rate of Technical Substitution (MRTS) - or Technical Rate of Substitution (TRS) - is the amount by which the quantity of one input has to be reduced ( − Δx2) when one extra unit of another input is used (Δx1 = 1), so that output remains constant ( ). 𝑀𝑃 Capital-saving: 𝑀𝑅𝑇𝑆𝐿,𝐾 = 𝑀𝑃 𝐿 rises 𝐾 Labor-saving: 𝑀𝑅𝑇𝑆𝐿,𝐾 = 𝑀𝑃𝐿 𝑀𝑃𝐾 declines Chapter 7 Explicit costs Explicit costs require a direct outlay of money by the firm Implicit costs Economic profit Accounting profit Long-run Costs Short-run Costs Total cost Implicit costs do not require an outlay of money by the firm. Economists measure a firm’s economic profit as total revenue minus total cost, including all opportunity costs (both explicit and implicit costs) Accountants measure accounting profit as the firm’s total revenue minus the firm’s explicit cost. All inputs are variable Some inputs cannot be freely chosen The cost of the optimal input choice for a given output level and given output prices is: 𝑇𝐶 𝑄, 𝑤, 𝑟 = 𝑤𝐿*𝑄, 𝑤, 𝑟 + 𝑟𝐾*𝑄, 𝑤, 𝑟 Chapter 8 Total cost function Average cost function The total cost function (TC) gives, for any set of input prices and for any output level, the minimum cost incurred by the firm. Total cost = TC(w,r,Q) The average cost function (AC) is found by computing total costs per unit of output. Average cost = 𝐴𝐶(𝑤, 𝑟, 𝑄) = Marginal cost function 𝑇𝐶(𝑤,𝑟,𝑄) 𝑄 The marginal cost function (MC) is found by computing the change in total costs for a change in output produced. Marginal cost = 𝑀𝐶(𝑤, 𝑟, 𝑄) = Economies of scale Diseconomies of scale Minimum efficient scale Output elasticity of total cost Short term costs of production Short-run average costs Average fixed costs Average variable costs Short-run average costs 𝜕𝑇𝐶(𝑤,𝑟,𝑄) 𝜕𝑄 If average cost decreases as output rises, all else equal, the cost function exhibits economies of scale. When the production function exhibits increasing returns to scale, the long run cost function exhibits economies of scale, so that AC(Q) decreases with Q, all else equal. If the average cost increases as output rises, all else equal, the cost function exhibits diseconomies of scale. When the production function exhibits decreasing returns to scale, the long run cost function exhibits diseconomies of scale, so that AC(Q) increases with Q, all else equal. The smallest quantity at which the long run average cost attains its minimum is called the minimum efficient scale (MES). The percentage change in total cost per one percent change in output is the output elasticity of total cost. 𝑑𝑇𝐶(𝑄) 𝑄 𝑀𝐶(𝑄) 𝜀𝑇𝐶,𝑄 = = 𝑑𝑆 𝑇𝐶(𝑄) 𝐴𝐶(𝑄) Short term costs of production may be divided into fixed costs and variable costs. STC(Q) = TFC + TVC(Q) Short-run average costs (SAC) can be determined by dividing the firm’s costs by the quantity of output it produces. SAC is the slope of a ray through the origin to STC. 𝐹𝑖𝑥𝑒𝑑 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡 𝑇𝐹𝐶 = 𝑄 𝑄𝑢𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑖𝑡𝑦 𝑉𝑎𝑟𝑖𝑎𝑏𝑙𝑒 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡 𝑇𝑉𝐶 Average Variable Costs (AVC) = 𝑄𝑢𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑖𝑡𝑦 = 𝑄 𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡 𝑆𝑇𝐶 Short-run average Costs (SAC) = 𝑄𝑢𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑖𝑡𝑦 = 𝑄 = 𝐹𝑖𝑥𝑒𝑑+𝑉𝑎𝑟𝑖𝑎𝑏𝑙𝑒 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡 = 𝐴𝐹𝐶 + 𝐴𝑉𝐶 𝑄𝑢𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑖𝑡𝑦 Average Fixed Costs (AFC) = Short-run Marginal cost Economies of scope Short-run Marginal cost (SMC) measures the increase in short term total cost that arises from an extra unit of production. 𝑑𝑆𝑇𝐶 𝑆𝑀𝐶 = 𝑑𝑄 Consider two outputs Q1 and Q2. Let production costs (at given input prices) of producing the two products separately be given by TC(Q1,0) and TC(0,Q2). Let production cost of producing jointly in one firm be TC(Q1,Q2). Economies of scope exist if joint production of given quantities of the two products is cheaper than separate production of the same quantities. TC(Q1,Q2) < TC(Q1,0) + TC(0,Q2) Chapter 9 Perfectly Competitive Markets Economic profit Economic Value Added Total Revenue Average Revenue Marginal Revenue Optimal profit in short run Shutdown Sunk Fixed Costs (SFC) 1. There are many buyers and sellers in the market (market is fragmented) *Each buyer’s purchases are so small that he/she has a negligible effect on market price. *Each seller’s sales are so small that he/she has an negligible impact on market price. Each seller’s input purchases are so small that he/she perceives no effect on input prices 2. Firms produce undifferentiated products in the sense that consumers perceive them to be identical 3. Consumers have perfect information about the prices all sellers in the market charge 4. Free entry: all firms (industry participants and new entrants)have equal access to resources (technology, inputs). Profit = Total Revenue (TR) –Total opportunity Cost (TC) A firm maximizes economic profit. Economic Value Added is a measure of economic profit. It is calculated as the difference between the Net Operating Profit After Tax and the opportunity cost of invested Capital. Total revenue (TR) for a firm is the selling price times the quantity sold : TR(Q) = (P x Q). In competition, the price is exogenous to the firm. Average revenue (AR) is total revenue per unit: equals price P Marginal revenue (MR) is the change in total revenue from an additional unit sold. For competitive firms, MR equals the price of the good. 1.Output is such that price equals marginal cost 2. Marginal cost is increasing at the optimal output 3. Profit is higher at optimal output than at zero output: producing is more profitable than temporarily shutting down production operations. A shutdown refers to a short-run decision not to produce anything during a specific period of time because of current market conditions. *The price at which the firm prefers to temporarily shut down operations and produce nothing is the shut down price, Ps *Profit at zero output depends on nature of costs: how much of the fixed cost can be recovered if production is shut down? The costs of the firm’s fixed input that are unavoidable at Q = 0 (i.e. sunk) and output insensitive for Q > 0 (i.e. fixed) Non-Sunk Fixed Costs (NSFK) Total Variable Costs (TVC) Supply Curve SRSC all fixed costs sunk SRSC some fixed costs are sunk SRSC all fixed costs non-sunk Short run supply curve of a competitive firm Market supply Long run Long-Run Supply Curve Firm exits Firm enters Long-run competitive equilibrium Constant cost industry The cost of the firm’s inputs that are avoidable if the firm produces zero output (i.e. nonsunk) and output insensitive for Q > 0 (i.e. fixed) TVC(Q): Total Variable Costs (output sensitive costs) In each case supply curve is the marginal cost curve to the extent that it lies above the curve (AVC+NSFC) Short Run Supply Curve when all fixed costs are sunk : NSFC = 0 *Shut down price is minimum average variable cost *Supply zero if price below shut down price *Supply curve coincides with marginal cost curve if price above minimum average variable cost (shut down price) *Losses perfectly possible at optimal output STC(Q) = SFC + NSFC + TVC(Q)where NSFC > 0 ANSC = TVC(Q)/Q + NSFC/Q… average non-sunk cost Shutdown if P < ANSC Section of the firm’s SMC-curve that lies above the SAC-curve is also the firm’s supply curve. *Coincides with vertical axis if price is below shutdown price *Coincides with marginal cost curve if price exceeds shutdown price *Shut down price is minimum of (AVC+ANSFC) *Average variable cost plus average fixed cost that is avoidable when not producing *Losses may be consistent with optimal behavior when not all fixed costs can be avoided at zero production The market supply at any price is the sum of the quantities each firm supplies at that price. The short run market supply curve is the horizontal sum of the individual firm supply curves. The long run is the period of time in which all the firm’s inputs can be adjusted, and the number of firms in the industry can change. *Firms adapt capacities (capital investment or disinvestment) *Depending on short-run profitability, there is entry in or exit out of the industry The marginal cost curve above the minimum point of its average cost curve In the long run, the firm exits if the revenue it would get from producing is less than its total cost. Exit if TR < TC Exit if TR/Q < TC/Q Exit if P < AC A firm will enter the industry if such an action would be profitable. Enter if TR > TC Enter if TR/Q > TC/Q Enter if P > AC All firms maximize profits, hence P=LMC(Q) Market demand equals supply All firms make zero economic profit If input prices remain constant when the industry expands, then the long-run market supply curve is horizontal. Increasing cost industry Decreasing cost industry Economic rent Producer surplus If input prices rise when an industry expands, the long-run supply curve is upward sloping If input prices decline when an industry expands, the long-run supply curve is downward sloping. Economic rent is the maximum willingness to pay for an input minus the reservation value of the input outside the industry Price P minus minimum price at which willing to supply ANSC Chapter 10 Excise tax Specific tax Ad valorem tax Tax incidence Deadweight loss Laffer curve Price ceiling Price floor World price Tariffs Import quota An excise tax(or a specific tax)is a tax per unit (denoted T) paid by either the consumer or the producer An ad valorem tax is a % tax Tax incidence is the manner in which the burden of a tax is shared among participants in a market A deadweight loss is the fall in total surplus that results from a market distortion, such as a tax. The Laffer curve depicts the relationship between tax rates and tax revenue. A tax cut would induce more people to work and thereby have the potential to increase tax revenues. A legal maximum on the price at which a good can be sold. A legal minimum on the price at which a good can be sold. Price floors sometimes are referred to as price supports. The effects of free trade can be shown by comparing the domestic price of a good without trade and the world price of the good. The world price refers to the price that prevails in the world market for that good. Tariffs are taxes levied by a government on goods imported into the government's own country. Tariffs sometimes are called duties. An import quota is a limit on the total number of units of a good that can be imported into the country. Chapter 11 Monopoly Natural monopoy Market Power Lerner Index of market power Multi-plant monopoly A firm is considered a monopoly if … *it is the sole seller of its product. *its product does not have close substitutes. An industry is a natural monopoly when a single firm can supply a good or service to an entire market at a smaller cost than could two or more firms An agent (not just monopolist) has Market Power if s/he can affect, through his/her own actions, the price that prevails in the market. Sometimes this is thought of as the degree to which a firm can raise price above marginal cost The Lerner Index of market power is the price-cost margin, (P*MC)/P*. This index ranges between 0 (for the competitive firm) and 1 (for a monopolist facing a unit elastic demand) 𝑃∗ − 𝑀𝐶(𝑄 ∗) 1 = ∗ 𝑃 𝜀𝑄𝐷 ,𝑃 The monopolist should make sure he allocates production so that the marginal costs in the two plants are equal at the optimal output levels, and that marginal cost equals marginal revenue Cartel A cartel is a group of firms that collusively determine the price and output in a market. In other words, a cartel acts as a single monopoly firm that maximizes total industry profit. Monopsony A market consisting of a single buyer an many sellers Chapter 12 Price discrimination Monopolist : uniform price Monopolist : price discrimination First-degree discrimination Perfect price discrimination Reservation price Second-degree discrimination Block pricing Two part tariff Linear two part tariff Third-degree discrimination Building ‘fences’ Versioning Tie-in sale Package tie-in sales Bundling Price discrimination is the business practice of selling the same good (i.e. identical products) at different prices to different customers, even though the production costs are the same. A monopolist charges a uniform price if it sets the same price for every unit of output sold. A monopolist price discriminates if it charges more than one price for its output. Individualized unit price The monopolist has information about the willingness to pay of each customer and can charge each customer a different price. First-degree price discrimination means the firm wants to produce the quantity at which price is exactly equal to marginal cost Customer’s willingness to pay Unit price depends on how much you buy Consumers pay different unit prices for different ‘blocks’ of output. The firm charges a lump sum fee for the right to buy the good plus a price per unit. Buyers must pay a fixed fee for the right to consume a good and a uniform price for each unit consumed : Cost for consumer = S + PQ If the firm knows the demand curve of the customer, an easy way to grasp all consumer surplus (and to maximize profit) is to *set P= MC *set S equal to the full consumer surplus at that price Unit price depends on group you belong to or on when you buy Identify different groups or segments with different demand curves (or different elasticities of demand) 𝑀𝑅1 (𝑄1 ) = 𝑀𝑅 2 (𝑄2 ) = 𝑀𝐶 Sometimes the firm can identify different groups with different price elasticities, but it may be difficult to charge a different price for the different groups. If more elastic groups care less for quality than less elastic groups then one way is to offer the product in (maybe slightly) different qualities Selling different versions of same product A tie-in sale occurs if customer can buy one product only if they agree to purchase another product as well. A tie-in sale may be used in place of price discrimination when the firm cannot observe the relative willingness to pay of different customers. Package tie-in sales (or bundling) occur when goods are combined so that customers cannot buy either good separately. Bundling may be used in place of price discrimination to increase producer surplus when consumers have different willingness to pay for the goods sold in the bundle. Bundling pair of goods → only if demands are negatively correlated Mixed bundling Optimal advertising Firms allow consumers to buy separate products as well as the bundle Optimal advertising implies marginal benefit of advertising equals its (total) marginal cost 𝜕𝑄 𝜕𝑇𝐶 𝜕𝑄 𝑃 =1+ 𝜕𝐴 𝜕𝑄 𝜕𝐴 Chapter 13 Imperfect competition Oligopoly Competitive interdependence The Cournot model of homogeneous goods oligopoly Homogeneous Bertrand Oligopoly Monopolistic Competition Stackelberg model of oligopoly Imperfect competition refers to those market structures that fall between perfect competition and pure monopoly. Only a few sellers; products can be homogeneous or heterogeneous; entry barriers Each firm faces downward-sloping demand because each is a large producer compared to the total market size Firm’s strategies and market outcomes depend on the behavior of competitors + the decisions of every firm affect the profits of competitors *Homogeneous Products, so there is only one price on the market *Non-cooperative behavior: firms determine strategies independently, without colluding with other firms *Simultaneous output decisions : each firm makes its strategic decision (at the same time) without prior observation of the other firm's decision. *Market price is not known until both firms have made their output choice *Homogeneous product, so a single price will result in equilibrium *Non-cooperative *Simultaneous price decisions : each firm makes its strategic decision without prior observation of the other firm's decision. Many firms selling products that are heterogeneous ( i.e., similar but not identical); no entry barriers. A situation in which one firm acts as a quantity leader, choosing its quantity first, with all other firms acting as followers. leader has first-mover advantage (larger profit) Dominant firm markets Horizontal Product Differentiation Vertical Product Differentiation Monopolistic competition Monopolistic competition ESR Monopolistic competition ELR Market with 1 dominant firm (usually in terms of market share) and a „competitive fringe‟ (usually large number of smaller firms) The dominant firm takes into account the behaviour of the competitive fringe in deciding the output it will put on the market (“Substitutability“) : at the same price, some consumers would prefer the characteristics of product A while other consumers would prefer the characteristics of product B. (“Superiority”) : one product is viewed as unambiguously better than another so that, at the same price Many Buyers Many Sellers Free entry and Exit (>< oligopoly) (Horizontal)Product Differentiation *Price exceeds MC *Positive profits attract new entrants Market *New entry implies declining demand for individual firms *Long run economic profit goes down to zero *Firms charge more than marginal cost Chapter 14 Game theory Strategy Simultaneous-move, one-shot games Nash equilibrium Prisoners’ dilemma Dominant strategy Dominated strategy Repeated games Trigger strategies Tit-for-tat strategy Sequential-move games Game tree Backward induction Strategic moves Predatory pricing The branch of microeconomics concerned with the analysis of optimal decision making in competitive situations. A plan for the actions that a player in a game will take under every conceivable circumstance that the player might face. *Situations that occur once in a relation between actors/players *Players make their moves simultaneously *The payoffs are the players‟ gains from a particular outcome of the game A Nash equilibrium is a situation in which (economic) actors each choose their best strategy given the strategies that all the others have chosen. Each player chooses a strategy that gives him/her the highest payoff, given the strategy chosen by the other player(s) in the game. The prisoners’ dilemma provides insight into the difficulty in maintaining cooperation. Often people (firms) fail to cooperate with one another even when cooperation would make them better off. A dominant strategy for a player is the best strategy for a player to follow, regardless of the strategies chosen by the other players. A player has a dominated strategy when she has another strategy that gives a higher payoff no matter what the other player does. In many real-world settings, players play the same game over and over again. Cooperation is much more likely in repeated games Cooperate only as long as everyone else does Revert to the harshest punishment possible Involves only one round of punishment for cheating Return to cooperation the next round Sequential-move games are games in which the order of moves matters A player that can move later in the game can see how others have played up to that point A game tree shows the different strategies that each player can follow in the game and the order in which those strategies get chosen. Game trees are often solved by starting at the end of the tree and, for each decision point, finding the optimal decision for the player at that point: A strategic move by a player A is a move early in a game that changes opponents‟ behavior later in the game in a way that is favorable to player A. The firm may charge an artificially low price to prevent potential rivals from entering.