Econ 281 Chapter 2 - University of Alberta

advertisement

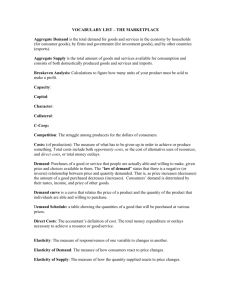

Chapter 2: Fundamentals of Welfare Economics -In order to evaluate government policies, we need a general framework -We can’t evaluate each policy on a case-bycase basis -ie: Lower interest rates lowers unemployment, then raising minimum wage increases unemployment (counter-productive) -Welfare Economics – the branch of economic theory concerned with the social desirability of alternate economic states and policies Chapter 2: Fundamentals of Welfare Economics Welfare Economics First Fundamental Theorem of Welfare Economics Second Fundamental Theorem of Welfare Economics Starting Point: Pure Exchange Economy We start with a simple model: – 2 people – 2 goods, each of fixed quantity – Determine good allocation The important results of this simple, 2person model hold in more real-world cases of many people and many commodities 3 Pure Exchange Economy Example Two people: Maka and Susan Two goods: Food (f) & Video Games (V) We put Maka on the origin, with the y-axis representing food and the x axis representing video games If we connect a “flipped” graph of Susan’s goods, we get an EDGEWORTH BOX, where y is all the food available and x is all the video games: 4 Maka’s Goods Graph Food Ou is Maka’s food, and Ox Is Maka’s Video Games u O Maka x Video Games 5 Edgeworth Box Food r y Susan O’ O’w is Susan’s food, and O’y is Susan’s Video Games Total food in the w market is Or(=O’s) and total Video Games is Os (=O’r) u O Maka x Video Games s Each point in the Edgeworth Box represents one possible good allocation 6 Edgeworth and utility We can then add INDIFFERENCE curves to Maka’s graph (each curve indicating all combinations of goods with the same utility) – Curves farther from O have a greater utility – (For a review of indifference curves, refer to Intermediate Microeconomics) We can then superimpose Susan’s utility curves – Curves farther from O’ have a greater utility 7 Maka’s Utility Curves Food Maka’s utility is greatest at M3 M3 M2 M1 O Maka Video Games 8 Edgeworth Box and Utility Susan O’ Susan has the highest utility at S3 r S1 Food S2 A At point A, Maka has utility of M3 and Susan has Utility of M3 S2 S3 M2 M1 O Maka s Video Games 9 Edgeworth Box and Utility Susan O’ If consumption is at A, Maka has utility M1 while Susan has utility S3 r Food A S3 O Maka B C Video Games By moving to point B and then point C, M3 Maka’s utility M2 increases while M1 Susan’s remains constant s 10 Pareto Efficiency Food r S3 O Maka C Susan O’ Point C, where the indifference curves barely touch is called PARETO EFFICIENT, as one person can’t be made better off M3 without harming the M2 other. M1 s Video Games 11 Pareto Efficiency When an allocation is NOT pareto efficient, it is wasteful (at least one person could be made better off) – Pareto efficiency evaluates the desirability of an allocation A PARETO IMPROVEMENT makes one person better off without making anyone else worth off (like the move from A to C) However, there may be more than one pareto improvement: 12 Pareto Efficiency Food r S3 S4 S5 A C E D O Maka Video Games Susan O’ If we start at point A: -C is a pareto improvement that makes Maka better off -D is a pareto improvement that M3 makes Susan better M2 off M1 -E is a pareto improvement that s makes both better off 13 The Contract Curve Assuming any possible starting point, we can find all possible pareto efficient points and join them to create a CONTRACT CURVE All along the contract curve, opposing indifferent curves are TANGENT to each other Since the slope of the indifference curve is the willingness to trade, or MARGINAL RATE OF SUBSTITUTION (x for y) (MRSxy), along this contract curve: Maka Susan MRSVf MRSVf Pareto Efficiency Condition 14 The Contract Curve Susan O’ Food r O Maka s Video Games 15 Starting Point: Economy with production A production economy can be analyzed using the PRODUCTION POSSIBILITIES CURVE/FRONTIER – The PPC shows all combinations of 2 goods that can be produced using available inputs – The slope of the PPC shows how much of one good must be sacrificed to produce more of the other good, or MARGINAL RATE OF TRANSFORMATION (x for y) (MRTSxy) Note that although the slope is negative, the negative is assumed and rarely shown in simple calculations 16 Production Possibilities Curve Here the MRTSpr is equal to (75)/(2-1)=-2, or two robots must be given up for an extra pizza. 10 9 8 The marginal cost of the 3rd pizza, or MCp=2 robots Robots 7 6 The marginal cost of the 6th and 7th robots, or MCr=1 pizza 5 4 Therefore, MRTSxy=MCx/MCy 3 2 Therefore, MRTSpr=2/1=2 1 1 2 3 4 5 Pizzas 6 7 8 17 Efficiency and Production If production is possible in an economy, the Pareto efficiency condition becomes: MRTxy MRS PersonA xy MRS PersonB xy Assume that MRT>MRS. A person could transform x into y at the rate of MRS and have x left over, thus increasing his utility Assume that MRT<MRS. A person could transform y in x at the rate of MRS and have y left over, thus increasing utility Pareto Efficiency cannot occur at inequality 18 Efficiency & Production Example Assume MRTpr=3/4 and MRSpr=2/4. – Therefore Maka could get 3 more robots by transforming 4 pizzas – BUT Maka only needs to get 2 robots for 4 pizzas to maintain utility – Therefore his utility increases from the extra robot, Pareto efficiency isn’t achieved We can therefore reinterpret Pareto efficiency as: MC x PersonA PersonB MRS xy MRS xy MC y 19 First Fundamental Theorem Of Welfare Economics IF 1) All consumers and producers act as perfect competitors (no one has market power) and 2) A market exists for each and every commodity Then Resource allocation is Pareto Efficient 20 First Fundamental Theorem of Welfare Economics Origins From microeconomic consumer theory, we know that: P MRS x Py Since this holds true for all people: MRS PersonA xy PersonA xy MRS PersonB xy Which is the first requirement for Pareto efficiency, before production is considered 21 First Fundamental Theorem of Welfare Economics Origins From basic economic theory, a perfect competitive firm produces where P=MC, therefore: MC P x MC y x Py But we know that MRT is the ratio of MC’s, therefore: P MRTxy x Py 22 First Fundamental Theorem of Welfare Economics Origins Again from microeconomic consumer theory, this changes to: But we know that MRT is the ratio of MC’s, therefore: P MRTxy x Py 23 The Law of Demand There is an inverse relationship between the quantity of anything that people will want to purchase and the price they must pay to obtain it: ceteris paribus (all else held equal) This causes demand curves to be downward sloping When prices increase, people buy less When prices decrease, people buy more 24 The Individual’s Demand Schedule A B C D E 5.00 4.00 3.00 2.00 1.00 5 Qn/yr 10 20 30 40 50 Price of Songs ($) Price/Unit $ A B 4 C 3 2 Change in Price Movement along 1 the Demand 0 10 20 30 D E 40 Number of Songs per Year 50 25 Note: We always graph P on vertical axis and Q on horizontal axis, but we write demand as Q as a function of P… If P is written as function of Q, it is called the inverse demand: Normal Form: Qd=100-2P Inverse form: P =50 - Qd/2 Markets defined by commodity, geography, time. 26 Movement Along Demand/ Changes in Quantity Demanded A change in a good’s own price change in quantity demanded – the same thing as a movement along – results in a the same demand curve. 27 Shifts/Changes in Demand* A change in one or more of the nonprice determinants of demand (income, tastes, etc) change in demand * – also called a shift in demand* – results in a *The whole demand schedule 28 A Shift in the Demand Suppose universities Curve outlaw the use of Suppose the federal MP3 Players Decrease in Demand Price of Songs ($) 5 government gives every student a SanDisk MP3 player 4 3 Increase in Demand 2 1 0 D3 20 30 40 50 60 D2 D1 70 80 Quantity of Songs Demanded 29 “Everything Else” : The “Determinants”/ “Shifters” of “Demand” Factors other than Price which affect “Demand” : 1) Income, wealth 2) Tastes and preferences 3) The price of related goods – Complements – Substitutes 4) Expectations – Future prices – Income – Product availability 5) Population (market size) What movement would these factors cause? 30 Review of Demand Terminology Demand: a schedule of quantities that will be bought/unit of time, at various prices, ceteris paribus. Quantity Demanded: a specific amount that will be demanded /unit of time at a specific price, ceteris paribus. There is a difference between between a change in the Quantity Demanded and a shift in Demand. 31 A policy to discourage smoking (no smoking in public buildings) shifts the demand curve left Price of Cigarettes, per pack Price of Cigarettes, per pack Shift vrs. Movement $2 D’ 10 A tax raises the price of cigarettes, resulting in a movement along the demand curve $4 $2 D D 20 Number of Cigarettes smoked per day 10 20 Number of Cigarettes smoked per day 32 Normal vrs. Inferior Goods For inferior goods, Demand increases When income decrease Price of Kraft Dinner Price of Chicken For normal goods, Demand decreases With income $2 D’ 10 $2 D’ D 20 Chicken eaten in a month D 10 20 30 Kraft Dinner eaten in a month 33 Supply: Profit The Cost side of the profit equation depends on the Costs of Production which depend on the kinds of inputs (factors of production) used the amount of each input used prices of inputs used technology 34 Supply: Definition A schedule that shows how much of a product a firm will supply at alternative prices for a given time period “ceteris paribus”. 35 The Law of Supply • The price of a product or service and the quantity supplied are directly related: “ceteris paribus” • Causes an upward sloping supply curve • The higher the price of a good, the more sellers will make available • The lower the price of a good, the fewer sellers will make available • All else being equal 36 The Individual Producer’s Supply Schedule Qnty of F $5 550 G 4 400 H 3 350 I 2 250 J 1 200 5 Price of Song ($) Price / Song Songs Supplied (thousands / year) F G 4 H 3 I 2 1 J Change in Price Movement along The Supply 0 100 200 300400500 600 Quantity of Songs Supplied (thousands of constant-quality units per year) 37 Movement Along Supply/ Changes in Quantity Supplied – A change in a good’s own price change in quantity supplied. that is, a movement along the supply curve. leads to a 38 Shifts/Changes in Supply A change in one or more of the nonprice determinants of supply leads to a – change in supply which is the same thing as a – shift of the supply curve. 39 A Shift in the Supply Curve When supply decreases the quantity supplied will be less at each price: ie: Singers form a union and successfully negotiate higher wages Price of Songs ($) 5 S2 a b 4 3 b c d S2 S1 d 2 1 0 20 40 60 When supply increases the quantity supplied will be greater at each price: ie: producer finds that she can use some cheaper singers from Newfoundland 80 100 120 140 Quantity of Songs Supplied (millions of constant-quality units per year) 40 “Everything Else” : The “Determinants”/“Shifters” of Supply Factors Supply other than Price that affect – 1) Cost of inputs (price in factor markets) – – – – 2) 3) 4) 5) Technology and Productivity Taxes and Subsidies Price Expectations (in the product market) Number of firms in the industry How will these shift supply? 41 Market Equilibrium Price & Quantity Market: where prices tend toward equality through the continuous interaction of buyers and sellers: the market forces of demand and supply Single Equilibrium Price 42 Putting Demand and Supply Together: Finding Market Equilibrium (1) (2) (3) Price per Constant-Quality Song Quantity Supplied (Songs per year) Quantity Demanded (Songs per year) (4) Difference (2) - (3) (Songs per year) (5) Condition $5 100 million 20 million 80 million Excess quantity supplied (surplus) 4 80 million 40 million 40 million Excess quantity supplied (surplus) 3 60 million 60 million 0 2 40 million 80 million -40 million Excess quantity demanded (shortage) 1 20 million 100 million -80 million Excess quantity demanded (shortage) 43 Market Equilibrium: Definition The condition in a S market when quantity supplied equals quantity Market clearing, or Q = Q E D S equilibrium, price demanded at a particular price; a point from A B where there tends to be no Excess quantity demanded at price $1 D 20 40 60 80 100 movement Excess quantity supplied at price $5 Price pef Song ($) 5 4 3 2 1 0 Quantity of Songs (millions of constant-quality units per year) 44 The Law of Supply & Demand The price of any good will adjust until the price is such that the quantity demanded is equal to the quantity supplied A high price will result in excess supply, pushing price down, and a low price will result in excess demand, pushing price up the market clears resulting in a single market clearing or equilibrium price. 45 Qd = 500 – 4p S Q = -100 + 2p p = price of cranberries (dollars per barrel) Q = demand or supply in millions of barrels per year 46 a. The equilibrium price of cranberries is calculated by equating demand to supply: Qd = QS … or… 500 – 4p = -100 + 2p …solving, 500+100=2p+4p p* = $100 b. plug equilibrium price into either demand or supply to get equilibrium quantity: Qd = 500-4d Qd = 500-4(100) Qd = 100 47 Example: The Market For Cranberries Price 125 Market Supply: P = 50 + QS/2 P*=100 50 Market Demand: P = 125 - Qd/4 Quantity 48 Example: The Market For Cranberries Price 125 P*=100 Market Supply: P = 50 + QS/2 • 50 Market Demand: P = 125 - Qd/4 Q* = 100 Quantity 49 Comparative Statics: Shifts in Demand &/or Supply •Suppose something in the demand &/or the supply “ceteris paribus” assumptions changes. •How is the MARKET affected? – 1.) Decide whether Demand &/or Supply is affected. – 2.) Decide in which direction the affected Demand &/or Supply will move. – 3.) Use a Demand and Supply diagram to determine the new equilibrium. – 4.) Calculate the new equilibrium (if possible) 50 Comparative Statics: Gas Prices Summer 2009: Gas prices at equilibrium at $1.07 per liter Winter arrives and certain drivers limit or end their driving for the season (shift in demand) –The new market equilibrium is $0.87 per liter Cold Weather causes a decrease in gas prices 51 Ford Escape Market Consider the market for Ford Escapes. 1. For each event identify whether demand or supply is affected. P1 2. Determine the direction of change. 3. Draw a diagram to illustrate how equilibrium is changed. S E1 D1 Q1 52 Ford Escape Market Steelworkers Strike Raises Steel Prices S2 E2 S1 P2 E1 P1 D Q2 Q1 53 Ford Escape Market New Automated Machinery Introduced S1 E1 S2 P1 P2 E2 D Q1 Q2 54 Ford Escape Market Price of Station Wagons Rises E2 S P2 E1 P1 D1 Q1 Q2 D2 55 Ford Escape Market Stock Market Crash Lowers Wealth S P1 P2 E1 E2 D2 Q2 Q1 D1 56 Simultaneous Shifts Example of a double shift. – 2 events 1. 2. supply demand only supply P, Q. only demand P, Q. 57 Shifts in Demand and in Supply S1 S 2 E2 P2 P1 E1 D1 Q1 Q2 D2 58 Simultaneous Shifts S1 P1 P2 S2 E1 E2 D1 Q1 Q2 D2 59 Simultaneous Shifts Example of a double shift. second possibility – 2 events 1. 2. supply demand only supply P, Q. only demand P, Q 60 Shifts in Demand and in Supply S1 S2 E1 P1 P2 E2 D2 D1 Q1Q2 61 Shifts in Demand and in Supply S1 S2 E P1 P 1 E2 2 D1 D2 Q2 Q1 62 Qd = 500 – 4p QS = -100 + 2p p = price of cranberries (dollars per barrel) Q = demand or supply in millions of barrels per year Assume that a plague reduced cranberry supply and fear of inflection likewise reduced cranberry demand so that: Qd = 400 – 4p QS = -200 + 2p 63 a. The new equilibrium price of cranberries is calculated by equating demand to supply: Qd = QS … or… 400 – 4p = -200 + 2p …solving, 400+200=2p+4p p* = $100 b. plug equilibrium price into either demand or supply to get equilibrium quantity: Qd = 400-4d Qd = 400-4(100) Qd = 0 64 Example: The Market For Cranberries Price 125 POLD=PNew New Market Supply: P = 100 + QS/2 Old Market Supply: P = 50 + QS/2 • 50 Old Market Demand: P = 125 - Qd/4 QNew QOLD Quantity New Market Demand: P = 100 - Qd/4 65 Elasticity: Percentage Change Consider the following: – An increase of 50 cents or an increase of 50% in the price of a hamburger – An increase of $100 or an increase of 1% in the price of a new car Percentage changes are easier to grasp than the amount of change – Therefore economists often use elasticities to examine percentage change or responsiveness 66 Price Elasticity of Demand Price Elasticity of Demand (Є Q,p) – The responsiveness of quantity demanded of a commodity to changes in its price – Related to the slope, but concerned with percentage changes 67 Price (dollars per pizza) Impact of a Change in Supply & Therefore Price on the Quantity Demanded S0 40.00 … a 30.00 large fall in price... S1 An increase in supply brings ... Large price change and small quantity change 20.00 10.00 … and a small increase in quantity 5.00 0 5 10 13 15 Da 20 25 Quantity (pizzas per hour) 68 Price (dollars per pizza) Impact of a Change in Supply… An increase in supply S0 brings ... 40.00 30.00 … a small fall in price... 20.00 15.00 Small price change and large quantity change Db 10.00 0 S1 … and a large increase in quantity 5 10 25 15 17 20 Quantity (pizzas per hour) 69 Solution: Price Elasticity of Demand Price Elasticity of Demand ЄQ,P Percentage change in quantity demanded Percentage change in price %Qd Q,P %P The ratio of the two percentages is a number without units. 70 Price Elasticity Example – Price of oil increases 10% – Quantity demanded decreases 1% - 1% Q,P .1 10% When calculating the price elasticity of demand, we often ignore the minus sign for % change in Q. 71 TYPES OF ELASTICITY -Hypothetical Demand Elasticities Product % Change in price (%P) % Change in quantity demanded (%QD) Elasticity (%QD/%P) Insulin + 10% 0% 0 Perfectly inelastic Basic Telephone service + 10% -1% .1 Inelastic Beef + 10% -10% 1.0 Unitarily elastic Bananas + 10% -30% 3.0Elastic 72 Price Elasticity Ranges: Extreme Price Elasticities Perfect elasticity, D Price P1 P0 0 8 Quantity Demanded per Year (millions of units) 30 D P1 Price Perfect inelasticity, zero elasticity, no matter how much Price changes, Quantity stays the same; insulin infinite elasticity, the slightest increase in price will lead to zero sales. P1 is the demand curve 0 Quantity Demanded per Year (millions of units) 73 Price Elasticity Ranges Summary from Table Elastic Demand %Q %P; Q,P 1 Unit Elastic %Q %P; Q,P 1 Inelastic Demand %Q %P; Q,P 1 74 Elasticity of Demand Calculating elasticity ЄQ,P or Change in Q Sum of quantities/2 ЄQ,P Change in P Sum of prices/2 Change in Q (Q1 Q2 )/2 or Change in P (P1 P2 )/2 Q ЄQ,P Avg. Q P Avg. P 75 Calculating the Elasticity of Demand Price (dollars/pizza) Original point 20.50 ΔP=1 Q /Qave 2/10 = Elasticity = =4 P/Pave 1/20 20.00 New point 19.50 D Qave =1/2(11+9)=10 Pave =1/2(20.50+19.50)=20 9 10 ΔQ=2 11 Quantity (pizzas/hour) 76 Elasticity of Demand (mid-point) Q =2 % Q =20% X 100 Q1 + Q2 (9 + 11) = 10 2 ЄQ,P = P = $1.00 % P =5% = ЄQ,P = 20% 4 = 5% X 100 P1 + P2 ($20.50 + $19.50) = $20 2 Always use the mid-point formula for calculating elasticity 77 Elasticity: Example You are the consulting economist to the Guelph transportation commission, The current fare is $.95 There are 17,500 riders per day For each $.10 increase in the fare, rider ship decreases by 10,000 riders per day. What is the price elasticity of demand at the current fare? Should fares be raised or lowered? What fare will maximize revenue? 78 Total Revenue and Elasticity Total Revenue = Price Per Good X # of Goods Sold TR = P X Q Assumption : Costs are constant 79 Elastic demand Price 1.10 .80 Unit elastic .55 Inelastic demand Quantity 0 55 (dollars) Total Revenue 3.00 When demand is elastic, price cut increases total revenue 110 Maximum total revenue When demand is inelastic, price cut decreases total revenue Quantity 0 55 110 80 Relationship Between Price Elasticity of Demand and Total Revenues Price Elasticity of Demand Effect of Price Change on Total Revenues (TR) Price Decrease Inelastic (ЄQ,P < 1) Unit-elastic Elastic TR (ЄQ,P = 1) No change (ЄQ,P > 1) TR Price Increase TR No change TR Note: It is possible to classify elasticity by observing the change in revenue from a price change 81 Question • • • • • 2 drivers - Tom & Jerry each drive to to a gas station. Before looking at the price, each places an order. Tom says, “I’d like 10 litres of gas”. Jerry says, “I’d like $10 of gas”. What is each driver’s price elasticity of demand? 82 Determinants of Price Elasticity of Demand Existence of substitutes –Goods are more price elastic if substitutes exist Share of budget –Goods are more price elastic when a consumer’s expenditure on the good is large (in dollar terms or relatively) Necessity –Goods are less price elastic when seen as a necessity 83 Market and Brand Elasticities Market and Brand Elasticities are not equal –Although a water addict is very price inelastic to the price of bottled water in general, he/she would quickly switch to another brand if only 1 brand of water increased in price –GENERALLY, Brand price elasticity of demand is higher than market price elasticity of demand 84 Qd = a – bp a,b are positive constants p is price -b is the slope a/b is the choke price (price at which nothing is sold) 85 the elasticity is Q,P = (Q/p)(p/Q) …definition… = -b(P/Q) Since the slope of the graph is –b. Therefore…elasticity falls from 0 to - along the linear demand curve, but slope is constant. if Qd = 400 – 10p, and p = 30, Q,P = (-10)(30)/(100) = -3 "elastic" 86 Changes in Elasticity Along a Linear Demand 1.10 Elastic (ЄQ,P > 1) 1.00 Price per Minute ($) .90 Unit-elastic (ЄQ,P = 1) .80 Inelastic (ЄQ,P < 1) .70 .60 .50 .40 .30 .20 D .10 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Quantity per Period (billions of minutes) 10 11 87 The Relationship Between Price Elasticity of Demand and Total Revenues for Cellular Phone Service Price Quantity Demanded Total Revenue Elasticity ЄQ,P $1.10 0 0 1.00 1 1.0 .90 2 1.8 .80 3 2.4 .70 4 2.8 .60 5 3.0 1.144 .50 6 3.0 1.000 Unit-elastic .40 7 2.8 .692 .30 8 2.4 .20 9 1.8 .467 .294 .10 10 1.0 .158 21.000 6.333 3.400 Elastic 2.143 Inelastic 88 Qd = Ap = elasticity of demand and is negative p = price A = constant Elasticity is constant, but the slope of demand falls from 0 to -. In another form, if Ln(Qd)=μLN(P), μ= Price Elasticity of Demand 89 Example: A Constant Elasticity versus a Linear Demand Curve Price • P Observed price and quantity Constant elasticity demand curve Linear demand curve 0 Q Quantity 90 Elasticity of Supply Calculating elasticity ЄQs,P Change in Q Change in P Sum of quantities/2 Sum of prices/2 or Change in Q ЄQs,P (Q1 Q2 )/2 or ЄQs,P Change in P (P1 P2 )/2 Q Avg. Q P Avg. P 91 Price (dollars per pizza) How a Change in Demand Changes Price and Quantity 40.00 An increase in demand brings ... Sa Large price change and small quantity change 30.00 20.00 10.00 0 … a large price rise... … and a small quantity increase 5 10 13 15 D1 20 25 D0 Quantity (pizzas per hour) 92 Price (dollars per pizza) How a Change in Demand Changes Price and Quantity 40.00 Small price change and large quantity change An increase in demand brings ... 30.00 21.00 20.00 Sb … a small 10.00 price rise... … and a large quantity increase D1 D0 0 5 10 15 20 25 Quantity (pizzas per hour) 93 Elasticity of Supply Elasticity of supply ranges – (from) Perfectly Elastic Supply Quantity supplied falls to 0 when there is any decrease in price – (to) Perfectly Inelastic Supply Quantity supplied is constant no matter what happens to price Notice: There is no total revenue test for supply since price and quantity are directly related 94 supply = 0 Price Price Supply Elasticity SRanges Elasticity of Elasticity of supply = S Quantity supplied is the same for any price! 0 Quantity Suppliers will offer ANY quantity at this price 0 Quantity 95 Elasticity of Supply: Depends On: 1. Resource substitution possibilities, -The more unique the resource, the more inelastic the supply. 2. Time frame for the supply decision, Momentary supply Long-run supply Short-run supply - Typically, the longer producers have to adjust to a price change, the more elastic is supply. 96 Long-Run Elasticity of Demand Elasticities can vary in the short run (when major changes cannot be made) and the long run. -For most goods, elasticity of demand is greater in the long run (curves are “flatter”) -People are more able to adjust to changes over time (slowly switch consumption) -For essential durable goods (ie: Cars), long-run demand elasticity is less (curves are “steeper”) -People can change their purchases or suppliers now, but eventually they have to buy new goods as old ones break 97 Long-Run Elasticity of Supply Elasticities can vary in the short run (when major changes cannot be made) and the long run. -For most goods, elasticity of supply is greater in the long run (curves are “flatter”) -Firms are more able to adjust to changes over time (slowly switch production) -For reusable goods (ie: Aluminum), long-run supply elasticity is less (curves are “steeper”) -People resell their stock when prices go up, but eventually their stock runs out 98 Supply Elasticity and the Long Run (most non-durable, non-essential goods) Price per Unit S1 S2 P1 Pe As time passes, the supply curve rotates to S2 and then to S3 and quantity supplied rises first to Q1 and then to Q2 Qe Q1 Q2 Quantity Supplied per Period 99 How Long is the Long Run? There is no set amount of time that puts a market into the long run – The long run could be a week or a year The long run is how long a consumer or firm takes to fully adjust to a price change – Time required to make major changes – Ie) Give up Pepsi Vanilla, Build more cost efficient Pepsi factory, secure a US Pepsi Vanilla supplier The short run is anything shorter than the long run 100 Cross Price Elasticity of Demand We’ve seen already that demand is affected by the price of substitutes and compliments – An increase in the price of a substitute increases demand – An increase in the price of a complement decrease demand This effect can be measured using cross price elasticity If the cross price elasticity is zero, the good is neither a complement nor a substitute 101 Cross Price Elasticity of Demand Є Qi,Pj Є Qi,Pj = Percentage change in quantity demanded of X Percentage change in price of Y Change in X --------------(X1 + X2)/2 / Change in Price of Y ---------------------------(Py1 + Py2)/2 Substitutes – Positive Cross Price Elasticity Compliments – Negative Cross Price Elasticity 102 Cross Price Elasticity of Demand Example “Recent cat attacks have prompted cat owners to buy guns for self-defense” Originally, 2 Econ students owned a cat. After the price of guns went from $100 to $200, only 1 Econ student owned a cat. Calculate the cross-price elasticity of demand 103 Cross-Price Elasticity Q = -1 % Qi =-66% X 100 Q1 + Q2 (2 + 1) = 1.5 2 ЄQ,P = P = $100 % PJ =66% = ЄQi,Pj = -66% = 66% -1 X 100 P1 + P2 ($100 + $200) = $150 2 Are cats and guns substitutes or compliments? 104 Income Elasticity of Demand Income Elasticity of demand refers to a HORIZONTAL SHIFT in the demand curve resulting from an income change Price elasticity of demand refers to a MOVEMENT ALONG THE DEMAND CURVE in response to a price change 105 Income Elasticity of Demand Є Q,I Є Q,I= Percentage change in quantity demanded Percentage change in income Change in Q --------------(Q1 + Q2)/2 / Change in M ---------------------------(M1 + M2)/2 Normal Good – Positive Shift/Elasticity Inferior Good – Negative Shift/Elasticity 106 Income Elasticity of Demand Example In New Zealand, the average family will own 4 Toyotas in their lifetime. If average Kiwi family income rose from $140K to $160K a year, the average Kiwi family would own 2 Toyotas over their lifetime Calculate Income Elasticity of Demand for Toyotas in New Zealand. Are Toyotas normal or inferior goods in New Zealand? 107 Income Elasticity of Demand Q = -2 % Q =-66% X 100 Q1 + Q2 (4 + 2) =3 2 ЄQ,I = I = $20K % I =13.3% = ЄQi,Pj = -66% 13.3% = -5 X 100 I1 + I2 ($140K + $160K) = $150K 2 In New Zealand, are Toyotas normal or inferior goods? Guess which brand is the luxury car. 108