Collaborative Capacity Guidance Document Draft Mar 8

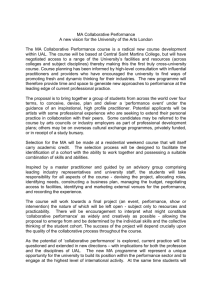

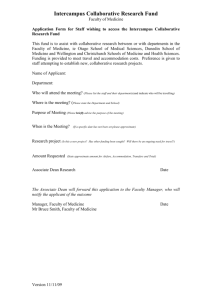

advertisement