CPC Bench Manual Draft (6-26-2015)

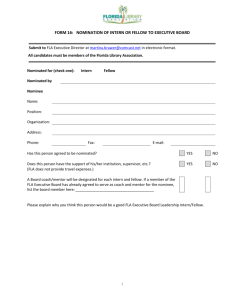

advertisement