MISSED: Missed Incidences of Signals of Safety Explored in Dialysis

advertisement

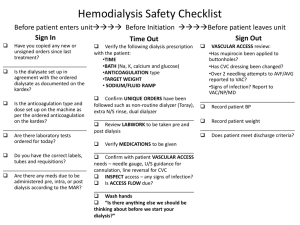

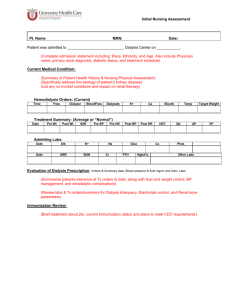

Ensuring Safety in the Dialysis Realm A medical director’s odyssey and perspective Paul E. Miller, MD Definition of Patient Safety • ‘Patient Safety: Freedom from accidental injury stemming from the processes of health care. These events include “errors,” “deviations,” and “accidents.” Safety emerges from the interaction of the components of the system; it does not reside in a person, device or department. Improving safety depends on learning how safety emerges from the interactions of the components and processes that minimize the likelihood of errors and maximize the likelihood of intercepting them when they occur. Patient safety is a subset of healthcare quality.’ • Quoted from the National ESRD Patient Safety Initiative 12/01/2001 “All that is great is simple” J.w. von Goethe • • • • • For nearly two decades I have observed repeat safety failures in diverse dialysis settings. Since there is no magic bullet or panacea to assure enduring safety in dialysis, team commitment to harm prevention for the entirety of every treatment is essential to mitigate safety failures. Since the profession has not adequately shared working practical solutions, each safety team must create its own strategy (often times with insufficient tools)—simplifying processes, closing safety gaps, and chipping away at pervasive attitudes that impede patient safety. P&Ps, however, are not pixie dust magical remedies to safety problems. Ingraining habits that always consider patient safety is more meaningful (and less risky regarding liability) than dictating every action in dialysis through complex and voluminous P&Ps (that dictate rather than guide actions)—especially considering high staff turnover in dialysis. Presented, from the vault of violations, is a compilation of humbling failure observations and experiences, educational ideas, safety projects, perspectives and lessons learned. • CAUTION: changing one aspect of a process may require adjustment elsewhere. It is important to consider the “what if” scenarios and monitor the effects of changes. This information cannot be used as a substitute for individualization of patient care by an appropriate prescriber. This is for information sharing purposes only. • “What are we to do when the irresistible force of the need to offer clinical advice meets with the immovable object of flawed evidence? All we can do is our best: give the advice, but alert the advisees to the flaws in the evidence on which it is based.” From the Oxford Center for Evidence Based Medicine http://www.cebm.net/?o=1025 Grades & Levels of Evidence • MISSED: Missed Incidences of Signals of Safety Explored in Dialysis Cracking the code to prevent failure mode Paul E. Miller, MD The Mystery • Why were patients falling, bleeding, dying? • Why were patients being transported to emergency rooms from dialysis? • Why were patients experiencing intolerance to dialysis? • Why wasn’t the MD notified of safety failures? • Why couldn’t staff consistently execute prescriptions as intended? • Why were we failing to consistently protect patients from harm? Discovery Process • • • • • • • • • Audits: reviewed safety practices, staffing characteristics and other aspects of care and management—staffing ratios, experience and workflows Reviewed: different protocols; frequency of rounding by nurse manager, medical director, physician prescriber vs non-physician prescribers; frequency of vitals and station visits; average clinic delivered time of dialysis; complexity of dialysis prescriptions; formulary size; options for dialyzers and antibiotics; characteristics including cost per treatment and days of dialysis operation Collected on call questions & observations of failures in different settings Analyzed the discrepancy in the frequency of failures with what was reported Reviewed incenter labs and orders including post dialysis emergency room encounters Reviewed missed patient (SOS)—signals of safety Observed dialysis patient care in acute, chronic and continuum of care encounters Collected tips from patients, staff, and prescribers Reviewed incidents, access complications, transitions to emergency rooms, cross coverage calls, emails to staff and administration, and other reported concerns Observations • • • • • • • • • • Set and forget attitudes included waiting for failure to respond—waiting for machine alarms to react to patient status. RNs were assessing before and after and might only visit during dialysis to administer medications or respond to problems. Lack of: direction for safety limits including boundaries for safe care such as ulftrafiltration rate and total fluid removal limits, minimum time prescriptions, prescribing limits for electrolytes, medication ceiling limits for ESAs, heparin, etc. Technicians were handling things by traditional routine react and respond. Lack of: recording & trending wrongfully suggested uneventful dialysis; simple visual reminders such as escalation protocols; ingrained habits for detailed systematic approaches to patient safety at the chair side Inconsistent escalation efforts; lack of checklists and algorithms for systematic approaches (beginning, end of day, before, during, and after dialysis, problem oriented, etc) Repeat failure episodes due to lack of effective problem solving and resolution assurance. Failure to consistently deliver or execute prescriptions as intended by the prescriber: lack of attention to detail; unapproved adjustments to machines, dialysis prescriptions (Rx), and knee-jerk dry weight changes were made on whims by staff (and patients). Knee-jerk antibiotic usage: rampant, unnecessary, and without attending MD notification or follow-up RN or nurse manager wrote admission/transient Rx without prescriber involvement Kt/V, URR values were often misinterpreted by patients & staff leading to knee-jerk reactions: shortening time, dialyzer size escalation, & incorrect advice from staff Pause, interrupted or Stop Therapies: air alarm failures and loss of blood in clotted circuits were rampant with improper set ups, access complications, and saline bags emptying. Multiple alarm resettings occurred for stop, pause, air detection, venous, conductivity, critical or other alarms without appropriate timely escalation Recurrent unexplained stop therapies caused by patient intentional clamping of blood lines underneath blankets Observations • • • • • • • • Fall Risks: door stops, trash cans, and other obstructions in walk path; machine leakage and liquids on floor not timely addressed; staff not escorting patients appropriately Antibiotics, labs, diagnostic and other procedures were ordered by non-credentialed MDs and were not followed up or approved by credentialed prescribers—lack of follow-up for complaints, problems, post dialysis events, procedures, referrals and diagnostic tests. Use of electronic calendar for reminders was non existent. Errors in dosing of Vancomycin & other antibiotics (abx) were common. Too little/too much without antibiotic protocol oversight by hospital pharmacy services & incenter monitoring; prescriber cross-coverage errors increased the failure rates of antibiotic dosing. Patients who received antibiotics in outpatient dialysis centers received additional dosing once presenting to emergency rooms same day or different day of dialysis (reasons: insufficient communication with no access to timely patient portal information or dialysis treatment encounter forms; rush to administer abx in emergency room settings for time tracking)—efforts to improve communication and reduce errors included handing patients a copy of treatment sheets with abx details and notifying ER if patients were transitioning to ER from dialysis. Staff used clotting substances from lab blood test tubes to promote hemostasis for access bleeding Medication administration such as Vancomycin and IV iron were being administered without any flow rate regulators and not according to safe time requirements—hypotensive episodes were occurring. BP cuffs not appropriately fitted leading to inaccurate readings Staff searched for orders to reduce HD time on evening shifts anticipating delays in NH or other transportation services. Occasionally, staff waited for on call prescriber (unfamiliar with patients) to solicit a desired order that differed from attending of record. These orders were often missed by attending through electronic order entry that did not require co-signatures of attending (examples: allowing catheter lock with tissue plasminogen activator [tPA] to remain until return to dialysis; shortening of dialysis; exceeding max UFR; allowing high sodium concentration profiling) Staff essentially encouraged sign off behavior by placing AMA/sign off forms at beginning of dialysis for patient signatures designating the time desired for termination of dialysis Observations • • • • • • • • • • • • Hemodynamics and intradialytic morbid events (IMEs): rescue saline administration, interrupted therapies, cramps, hypotension, n/v, post dialysis episodes of care for emergency room visits, and other actions and findings often considered as surrogates of patient clinical intolerance were not accurately reported or trended. If captured, event description (severity, # episodes during same treatment) were not meaningfully trended. Blood loss: clotted systems and dialyzers and post venipuncture bleeding episodes were common; there was a lack of identifying, monitoring and escalating concerns for at risk bleeding patients with multiple blood thinners or those exhibiting easy bruising and bleeding; failure to adequately secure lines including repositioning of needles; clamps being used inappropriately on the visually impaired and others with contraindications The perception of “safe in dialysis” was not realistic for staff nor consistent with the perceptions by the patients they were serving Process failure for identifying, escalating, and recording of adverse events and near misses led to inaccurate reporting and reduced effectiveness of QAPI. Antiquated data analysis and reporting contributed to safety failures. Failures of timely reporting episodes of care were concerning. Traditional and newly identified barriers that impede safety efforts were identified. RNs, nurse managers failed to accompany rounding prescribers. Transitions such as admits to rehab, NH, LTAC facilities: dialysis and other needs were missed for days Newly designed safety projects by medical director were slow to move through the creeping committee process Blood volume monitoring device effectiveness was reduced by inadequate monitoring and focus Harm from unnecessary lower extremity arterial procedures in asymptomatic patients Tourniquets for cannulation commonly misused and forgotten in place Observations • • • • • • Angioaccess: HD access referral and catheter removal delays Transient care and on-call coverage decisions were inconsistent and often not reported to attending of record. Orders from on-call prescribers were not readily available to review (as with co-signature orders) once electronic records started. No easily viewable longitudinal charting existed (of a patient’s specific outstanding problems “to do list” for MD or others to review at time of patient encounter or clinical review). Despite progress notes having structure for effective systematic approaches as creatively designed for problem capture by IT (problem oriented medical records), MDs, staff were not using SOAP notes appropriately. Assessing care upon return to dialysis was inconsistent. Advanced directives and resuscitative discussions were not consistently being delivered, and not being discussed by attendings frequently enough especially for those patients in declining health. Imminent safety failures for those unfortunate, yet, inevitable declining health individuals were not timely addressed. Admission of patients without medical director review led to inappropriate admissions of high acuity patients that could not safely be treated in the outpatient dialysis settings. This often consumed staff time for higher care attention needs in already challenging evening shifts. Infectious transmission risks were concerning. Several patients were comfort care appropriate and were not presented with those options prior to admission. Formularies in hospitals and outpatient centers often times excluded nephrologist and medical director involvement in the selection and safety surveillance processes. Observations • • • • • • • • QAPI was sloppy. Some team members were quick to sabotage improvement projects using misleading and inaccurate data. 4 hour minimum prescription led to reduced attempts at gaming the system on lab testing days (treatments)—traditional efforts to convince patients to stay longer just to make it appear that we were achieving goals Abuse of medications such as IV anti-emetics and antihistamines: use not trended for quality and safety analysis GI preps not safely administered to patients including magnesium and phosphate-based Complex mix and match prescriptions—changing dialysates at different hours Hospitals refused to allow certain notification, admit, prn and transition standing orders because of liability reasons—nurses could not adhere to requirements of lab notifications for critical labs When standing orders were adopted by hospitals for dialysis patients and appropriate timely communication with nephrology occurred, less chances for harm resulted: volume management; medication reconciliation; missed dialysis; electrolyte imbalance; timely antibiotic administration; and less unnecessary testing and procedures Coordinating care in communities counts: emergency rooms often mismanaged dialysis patients— early nephrology communication and direction reduced harm; we encouraged ER (and for any transition in care) to call nephrology for immediate communication upon presentation Focus fatigue and alarm fatigue were disturbing. “Going through the motions” was problematic Observations • • • • • • • Direct admissions often led to dangerous delays: patients not monitored safely, not receiving antibiotics, dialysis or other care timely. Formulary options for rapidly administered antibiotics at dialysis clinics were encouraged (prior to ER transfer for unstable septic appearing patients who were not tolerating dialysis) instead of waiting hours to receive after leaving dialysis Emergency room visits where patients were transferred directly to inpatient dialysis in hospital prior to receiving RN assessment: failure to timely notify nephrology and on call dialysis nurse immediately from ER led to dangerous delays; hand offs lacked effectiveness and urgent orders were not timely acted upon (including abx) until hours later when patients transitioned from acute dialysis to hospital rooms; patients were often assumed to be safe enough for dialysis in the hospital dialysis acute program center hoping that their condition would improve after tx— occasionally, patients were too unstable for the level of care that could be safely supported with the dialysis staffing ratios Emergency room and hospital staff failures when accessing PD and HD catheters: inadequate infection control; high chest PD catheters accessed as HD catheters Bladder indwelling catheters placed in anuric dialysis patients risked trauma and infections Dialysis therapies in ICU settings: partially trained ICU staff led to safety failures Parathyroid surgical patients: calcium carbonate dosing—prevention of constipation and alkalosis monitoring required adjustment of prescription and increased stool softener approaches; holding cinacalcet 1 week prior to sx Attention to optimal volume status each treatment was lacking—failure to escalate, challenge, adjust and record Observations • • • • • • • • • Patients were not adequately prepared prior to surgical procedures (example: parathyroidectomy—cinacalcet not held or blood thinners) and attendings were not aware of scheduled procedures RN ramping of dialyzer size without prescriber input was problematic Non-RN technicians were preparing and administering anticoagulation through circuit Aggregation of staff away from patients on treatment floor was problematic LTAC patients in the outpatient setting were often unstable as well as infected with multi-resistant organisms Lab: errors, notification protocols, and validation methods were concerning; (same color cap for test tubes for hemoglobin also for clearances led to collection, preparation and lab analysis errors) Testing of hemoglobins (Hgb) in volume excess states resulted in falsely low Hgb levels, pseudo-resistant erythropoietin dx, and unnecessary ramping of ESA dosing Intravenous medication administration: infectious exposure risks (including multi-use vial technique) and other safety concerns each dialysis P&Ps were out of date, not practiced—just for show it seemed Observations • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Large bore cannulation needle escalation caused greater bleeding episodes and trauma risks Non-adherence for outpatient medications: sometimes ramping of doses resulted in problems when patients decided to become more adherent—we transitioned more to oral observed therapy Lack of ability to contact patients on call when notified by lab outside of dialysis clinic hours for bacteremia (or other critical labs); uncertain if any treatment or appropriate treatment had been delivered Back to back (two days in a row) dialysis did not consider dialysate prescriptions Dialysis lines were crossing over patients and poorly secured for patient movement Technicians and nurses were distracted: reading books, on phones, watching TV, gossiping, playing games MDs would not respond timely to calls from units or conscientiously manage patient care Infrequent or pass-through princess-waving prescriber rounds Blood product transfusion practices were concerning; often, patients failed to show Reuse processing and quality control were problematic Blood draw and processing was problematic Patients who should have stayed within close observation were allowed to be alone in waiting room prior to and after dialysis Medications such as aluminum based anti-ulcer therapies, metformin, and other contraindicated medications were missed More than one form of ESA in clinic resulted in mistakes when administered Patients were allowed to leave treatment floor still holding accesses without verification of hemostasis Observations • • • • • • • • • Treatment sheets did not report verification of which dialysate, ultrafiltration or sodium profile administered HD machine conductivity alarm ranges: tightening & more frequent validation reduced errors in delivery No effective vascular access program including surveillance: AV access placement delays; excessive primary failure rates PD patients: missed signs for uremia and volume excess; non-adherence for treatments or self-administration of ESAs and other medications; PD patients were stacking fluid. Human factors errors were rampant Pacemakers placed for hyperkalemia related reversible bradyarrhythmias, central lines, PICC lines, and subclavian mediports placed compromising future dialysis access placement without nephrology involvement; we educated CV and other surgeons, patients and others regarding preservation of patient pipelines for future hemodialysis access Efforts to transition patients faster from hospital settings to outpatient care have increased the episodes of care resulting from patients too unstable and not medically suitable/optimized for return to outpatient dialysis. Frequency of missed and incomplete dialysis sessions has increased with complex outpatient treatment plans that included daily hyperbaric and other outpatient therapies—burden or scheduling conflicts that resulted in patients deciding to skip or shorten dialysis. Misconceptions from patients’ non-nephrology prescribers and emergency room physicians about the ability of outpatient dialysis settings to safely care for unstable patients. There was a common misunderstanding that outpatient dialysis clinics can easily manipulate dialysis schedules to handle such things as on demand dialysis and daily dialysis for pericardial effusions; or, that every dialysis clinic has the ability to safely manhandle severely obese mobility limited clients. Prolonged outpatient hospital care for ARF dialysis patients led to increased errors as a result of fragmented care without the continuity that exists in outpatient dialysis centers. Patients were cheated of quality care especially with a lack of nephrology medical director oversight for acute dialysis programs. Patients experienced hardships for travel which compromised employment and QoL. Observations • • • • • • Manual transfer of handwritten treatment sheets to electronic documentation resulted in transcription failures—subsequently, resulted in failures when treating staff did not recognize that post dialysis weights were incorrectly entered and not detected; frequent inconsistent units of measure errors Access complications and other episodes of care were being directed by “autopilot” protocols to emergency rooms and interventional suites without MD involvement—this led to delayed definitive access care and compromised catheter reduction and prevention strategies; sticking problematic accesses; patients were not educated to protect future fistula routes or subclavian veins Knee-jerk protocols (or orders by X-coverage MDs) changed dialysate baths without consideration for lab errors or inconsistent lab results from usual patient labs—resulting in unintended management. The effects of missed treatments and access complications were often not considered which may result in a change from stable baseline labs—and usually do not warrant a change of stable prescriptions. Such knee-jerk Rx changes risked prolonged exposure to patients until repeat testing; ramping of bicarbonate was done without MD involvement and resulted in symptomatic alkalosis. Missed signals of safety (trending and single signal abnormal lab results) resulted in response delays Treatment sheets were being printed out prior to day of dialysis. Electronic prescribing protocol changes and treatment sheet lab automatic population of results were sometimes missed. If internet system was down, other patient information could also suffer gaps. We developed a clinic buddy system for faxing over updated treatment sheets from another server region (which still was not a cure for major outages). Lack of updated identifying facial image (picture) corresponding to patient names on electronic records increased the risk of confusion and communication mistakes by rounding prescribers and new team members including during patient review conferences. Pictures of unstable patients as the image changes over time on dialysis would have been beneficial for family patient conferences and advanced directive discussions. Observations • • • • • • • • • • • • • Staff cut corners with access cleaning methods; infiltrations were rampant Several medications were being missed as dangerously contraindicated or not followed closely enough for monitoring levels or dose adjustment Staff removed the tape securing access needles while high speed blood pumps ran which contributed to infiltrations and blood loss episodes Issues of concern were not being brought forward for timely escalation and were held until once a month QAPI meetings for discussion. A lack of trending (including labs and IMEs) adversely affected problem solving Repositioning of needles were done with insufficient consideration for infection control measures Difficult access sticks: staff were sticking multiple times even on non-functioning accesses Infiltrations of AV access as a result of faulty arm positioning (arms resting on arm rests of chair when body positioning slumped lower in chair resulting in arm fatigue causing jerking of arm downward) Dangerous medication ramping for heparin anticoagulation was being done without timely MD oversight & without heparin Rx boundaries (missing recirculation access problems and early clotting of systems with air) Laboratory results: delayed review by first line of defense clinic personnel and also prescriber; results often misinterpreted as window in time results (not trending) and misstep actions occurred frequently. WBC and platelet count changes often not captured Problems with mathematical calculations for volume assessment and adjustments at machine level Blood was not being returned when patients were disconnected from circuit for restroom breaks RN initial assessment often did not occur until after first hour of dialysis; findings of no volume removal settings even after long interdialytic periods for patients with no RRF was problematic Patients who missed dialysis for several treatments were allowed to return to dialysis without assessment in health status. When dialysis was missed for access or other reasons, MD was rarely contacted to assess urgency and mitigate harm for those at most risk of sudden demise Observations • • • • • • • • • Disaster transient patients—unknown infectious status: machines not disinfected post treatment; communication failures among outpatient facilities, ERs, and inpatient settings led to dangerously prolonged waits for dialysis patients Procedures: efforts to coordinate dialysis around procedures (not on same day) to avoid complications were not a priority; often times, procedures were canceled as a result of not receiving dialysis the day prior Failed transplants—conversion to dialysis: immunosuppression not tapered timely Anticoagulation: as patients were transitioned from catheter to AV access, reductions in heparin were missed resulting in excess bleeding complications Delays in prescribing ESAs, Iron and BMD treatment occurred—even when electronic dosing protocols became available, enrolling new patients was delayed Patients were receiving IV iron despite active infectious processes: IT team wisely responded with automated intuitive actions that held IV iron dosing when infection suspected RNs had more time to focus on patient care as e-Rx protocols & automated QAPI reports deployed. Average use of ESAs reduced to < 2500 units/tx with e-Rx Prescribers were able to focus on key quality trending parameters as IT data formats & autopopulation on treatment (Tx) sheets, encounter forms, and QAPI reports occurred Refusal of some hospitals to establish nephrology safety and quality committees (and not having quality nephrologist trained medical director oversight) led to inadequate quality improvement efforts to augment community dialysis patient coordination of care Observations • • • • • • • • • • • Patients who were returning from hospitals and other encounters were often volume overloaded. Accurate volume assessment and need for extra dialysis sessions within first week of return from those transitions were missed resulting in repeat hospitalizations. Optimal volume status assessment (dry weight) mismatching was widespread. Dry weights were erroneously being adjusted for cramps without MD review; patients were becoming volume overloaded—stacking fluid Larger call groups: additional problems of not having consistency for who was being called to report repeat failures. A lack of continuity presented challenges Patient medicine and dialysis prescriptions were being renewed by RN without timely MD review Early identification and isolation for preventing spread of contagious illnesses such as MRSA, VRE, C. Diff, diarrhea and URIs were inconsistent. Lack of complete commitment to excellence and safety in every action for every team member Staff were transporting sharps several feet to reach containers Inadequate dialysis: ultrafiltration only (dialysate bypass) therapies did not adhere to safe time limits and boundaries; problematic dialysis was not escalated for immediate action to reduce chances of harm from recirculating blood and hemoconcentration of electrolytes Incenter stethoscope use ignored infection control practices especially for AV assessment PD patients with unstable gait: large volume dwells risked fall harm during ambulation Staff did not recognize the significance of change of patient status suggesting instability, or the significance of when in dialysis events occurred (such as when IMEs occurred, early, mid, late or post dialysis) Observations • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Timely recognition, action, and follow-through beyond immediate problem solving to achieve sustained resolution and prevention of recurrence were lacking. Lack of communication throughout the team continuum; failure to immediately escalate concerns Failure to follow P&Ps (ceilings; floors; limits; lack of systematic approaches using visual reminder aids) Distractions (lack of focus on patient and task as hand) Lack of staff and patient (overall team) training, engagement and commitment to the partnership for patient safety: subsequent generation loss—critical gaps in training: technicians were training new nurses Philosophies: that encourage reactive rather than proactive care approaches; that cheat patients of Time for the Dime; that think of patients as out of sight, out of mind when they are not present in the facility Lack of safe simplification of complex prescriptions & consolidation of standing orders led to recurring safety failure events Breaching safety thresholds with shock-and-awe treatments: electrolytes and solutes; volume assessment and rate of removal; medication error and other exposure risks Rogue prescribers and independent end-operator users and communication barriers including poor quality sound transmission through cellular phones: failure opportunities without safe boundaries Lack of prescribing oversight of non-experienced prescribers On-call coverage failures for followup and inadequate information sharing Too many options for medications, dialysates, standing orders and protocols for different prescribers; and therapies that invite mistakes Information sharing gaps: medications, compliance, and encounters or episodes of care. Perception of who is delegated what role as prescribers across the continuum was a common cause of delays in treatment waiting on others rather than handling in the facilities as was done in the past—medication prior-approvals added to that burden. Reactive practices for disinfection of devices and water system waited for failures instead of preventing them Unilateral administrative decisions regarding shortening supplies to 2 weeks became problematic for shortages and disaster times Observations • • • • • • • • • • Home program efforts initially were not fully supported & often discouraged by HD staff who feared home growth would affect schedules and job security. Some nurse managers avoided patient interaction and supervisory floor time by arriving late, hiding in their offices most of the day, and leaving early. Clinics that had very engaged nurse managers on the floor consistently performed better with less failure events. Electrolytes were out of range from expected for patients presenting to emergency rooms after dialysis representing mismatching of prescription to delivery of intended prescription. Concerning lab results “ within range” were being missed regularly With more than one dialysate buffer type bath and machines that defaulted to previous settings, errors in delivery were rampant Weekends and nights presented the most frequent episodes of care and safety failures: staff inconsistency; lack of continuity; reduced MD, nurse manager and medical director presence; and less staff experience contributed to the preventable failures. These shifts also had the highest at risk patients. Lack of adequate updated access to patient portal information New patient education was inconsistent, drawn out, and without a systematic approach Dips and spikes for anemia management—missing transfusions, ESAs stopped Multiple alarm resetting occurred for stop/pause, air detection, venous, conductivity, critical or other alarms: immediate escalation was inconsistent Problem Solving and Practical Solutions • Identify safety gaps, barriers, and research best practices • Commonality regarding causal and contributing factors; execute methods that maximize mitigation efforts for several hazards • Refine surveillance and ongoing process improvement strategies: select surrogates for clinical intolerance that are meaningful for patient safety—short term and long term • Reasoning and problem solving strategies: deductive reasoning, inductive reasoning, question assumptions, reason by analogy • Refining existing pathways, creating new algorithms, and simplifying processes to improve safety and reduce errors in care • Reducing extra steps that present extra risks of human error and harm to patients: example—transitioned IV iron administration to heparin pump which offered a non-FDA approved (albeit, well studied for safety) approach for reducing the flow rate failures that resulted in hypotensive episodes with IV iron Barriers to improve safety • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Lack of awareness to the recurring safety failure problems: “Safe” perception that does not always consider harm prevention, hemodynamic instability and clinical tolerance or intolerance Lack of enough resources designated to IT and process improvement to add another project; no patient portal or secured messaging system where all encounters could at least be partially captured and communicated Patients, providers, prescribers, medical directors, administrators, and other team members including rogue prescribers—traditional training and acceptance of mediocrity interfered with open mindedness for change Failure to initiate, support, and sustain a culture-of-safety program at every level commensurate with ability (including the utilization of electronic decision support, predictive analytics, and practical tools to assist the naked eye as well as supporting a patient portal) Patient engagement; recurring staff creep; staffing ratios & turnover; lack of adequate staff performance Lack of safety certification training in dialysis; pervasive attitudes that corrupt effectiveness. Perception of value: cost is too great for life saved—safety is not the priority. Lack of a standardized safety and efficacy grading scale for scoring each dialysis session No effective renal specific registry for adverse event reporting and failure analysis research Top down administrative philosophies: marginalize medical director authority and involvement including selection of devices and formulary; mandate governing body sign-off for safety programs that overrule/usurp MD— perception that the governing body controls the safety process, not the medical director Unprofessional competitive relationships that preclude non-medical director prescriber opinions and failure observations from being taken seriously by staff Lack of complete commitment to excellence and safety in every action Insidious nature of dialysis safety failures preventing staff from perceiving adverse effects of actions Medical directors and providers fear of losing patients by enforcing higher standards Lab providers not executing e-alerts customized for prescriber preference and available to patients through patient portals Initial goals for safety improvement identified • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Reduce the harm of hemodialysis: reduce intradialytic morbid events, improve patient perception & clinical tolerance in dialysis (reduce intolerance)—prevent the shock-and-awe of therapies Simplify prescriptions, consolidate protocols, prevent knee-jerk reactions, & reduce interrupted Tx’s Re-educate staff to emphasize safe in every action, every step, all the time, all the way, throughout the day—this involved reducing the distractions and improving the focus on patients Crimp on Creep exhibited by staff over time; employ less Yes people and less minimalists Set safety limits and boundaries for all aspects of care and ingrain the staff in the principles of safe boundaries of care—(buoys and boundaries) Improve the all eyes-on-patients and all hands-on-deck approaches especially during shift transitions Improve communication within the clinic and beyond to outside encounters of care—reduce gaps Reduce falls with the buddy system for escorting patients to and from stations Reduce catheters; mitigate infection risks for button hole technique with extra steps of disinfection (and avoidance of buttonhole technique at other unfamiliar locations such as at hospital, travel, or with inexperienced personnel) Consolidate medications, reduce excessive poly pharmacy, and identify categories of medications that may pose additional risk to patients Use proven e-prescribing protocols where possible to reduce human errors, delays, & time-to-treatment Reduce blood loss episodes of care; educate patients about unnecessary procedures Emphasize patient responsibility, home options, PD first and catheter last strategies Early referral for education: new dialysis patient packet for systematic education and reduction in time for action Projects, Perils and Pearls Clamp on Cramps in Dialysis: Treading on Treacherous Safety project to mitigate ischemic injury in dialysis & reduce clinical intolerance Paul E. Miller, MD Identified Need • Patient discomfort and perception of QoL on dialysis • Frequent cramps (prescribers were not aware) leading to excess saline resuscitation and counteracting efforts to reduce sodium and chloride loading (including avoidance of sodium profile variation or modeling techniques) • Prevention of intradialytic morbid events (IMEs)—cardiovascular ischemic/instability events and patient harm caused by dialysis therapies; often times, IMEs reoccurred during same treatment as interventions did not focus on prevention/sustained resolution • Increased sign-offs and no shows • Missed mark for optimal volume status (dry weight) management • Increased hospitalizations for volume overload • Reduce factors such as cramps, shortened dialysis, and IV saline administration which may adversely affect uremic acidosis management Strategy Summary • • • • • SPOT-ON: Simplifying Prescriptions over Time S^TOP: Safety at Top of the Hour RN Rounds (PD first)—Home options Improve Patient Experience in Dialysis—(HO-i-PE) Be Smart, Do Your Part—Health Begins at home Patient Engagement (dietary discretion emphasis) e-ALERTS: Electronic Alerts for abnormal labs, episodes of care, return to dialysis, trending, and signals of safety suggesting failures or impending doom in dialysis [proposed expansion of current safety alerts system] • • SAFETY: Safety Assurances from Everyone Treating You—educational program Developed new standard dialysate bath K 2.5, Mag 1.3—approach to reduce electrolyte shift risks associated with longer therapies Set boundaries—reduced HD alkali administration and administered oral bicarbonate daily therapies Max BFR 400 and DFR 600, sodium (min 135, max 138), and UFR (max 10mL/Kg/Hour) Minimum time on dialysis to 4 hours: Trading Time for Tolerance improved clinical tolerance of Hemodialysis; allowed flexibility for increasing time through the Time Increase for Patient Safety Standing orders Dialysate temp 35; vitals monitored closely every 15 minutes and changes in trending escalated Failure analysis of cramping episodes: identified cramps as early, mid, late and whether associated with hypotension 30 day QAPI trending: cramps, hypotension, and UFR failures; each treatment shows UFR results For the rare patient with unrelenting clinical intolerance—transitioned to PD if at all possible • • • • • • • Results • Dramatic improvement in clinical tolerance of dialysis and reduced episodes of care • Reduction in rescue saline use per treatment • Improvement in lab values for patients • Improvement in achieving optimal volume status • Safety limit for total UF/hour (UFR at 10cc/hour/Kg) was objectively monitored at each treatment and trended over time. Tickler with maximum fluid removal was defaulted on each treatment sheet to mitigate calculation errors and for those who have intolerance to this rate (excessive large volume removals/hour or per treatment for larger body size and other pertinent safety tickler information). • Preventing knee-jerk dry weight adjustments and monitoring leaving heavy were essential for reducing undesired consequences. Extra treatment per month beneficial for some patients SPOT-on: Simplifying Prescriptions over Time Safety project Paul E. Miller, MD Identified need and details • • • • • • • • • • Recurrent errors in executing therapies not as intended by prescriber Knee-jerk reactions (changing of prescriptions) to labs that were problematic Reduce ischemic episodes of care—to reduce harm and improve QOL post treatments including TTR (time to recovery), we set all prescriptions at a minimum of 4 hours and have the philosophy of “Get off the floor with 4” Some patients sign-off; however, we have safely improved overall time on dialysis 4 hour minimum treatment prescription time (keep it low and slow); max BFR 400 (select BFR wisely if used above 400 as this resulted in worse patient symptoms). Dialysate temperature lowering (standard 35) Lower dialysate flow rate (DFR) 600 maximum: mitigated unexpected ultrafiltration failures (resulting in IMEs, leaving heavy) using some dialysis machines with higher DFRs Oxygen therapy encouraged Reduce BP medication use prior to HD and avoid certain classes such as nitrates Once a month extra treatment offered to help reduce volume stacking and consequences for those who are destined for self-destruction; staff have the flexibility to increase time to safely remain within UFR limits SPOT-on: Simplifying Prescriptions over Time • Much more accuracy in what is prescribed (Rx) and what is delivered (dd) • We individualize what we realistically can, consistently and safely, and standardize what we can with similar scrutiny • Simplified prescriptions, reduced need for extra human calculations and adjustments; used lower (BFR, DFR, temperature, bicarbonate, sodium), longer (Tx time), slower (UF rate), and higher (electrolyte concentration K, Mag); administered oral bicarbonate therapy daily maintaining buffer stores & reducing intradialytic shifts. Perceived clinical tolerance improved as well as improved consistency of lab results. • Default Rx: 2.25 Ca, 2.5 K+, 1.3 Mag; 35 temp—we avoid sodium variance profiling or modeling • Patients feel better with less episodes of care. • Scheduling around increased times can be problematic for high volume packed clinics. Anticipate more patients leaving heavy as maximum UFR is lowered < 10cc/kg/hour if HD time is not increased sufficiently > 4 hours SPOT-on: Simplifying Prescriptions over Time • • • • • • • • Every three months try two days in a row dialysis to assist with volume challenging Daily stool softeners (unless loose stools) and sodium restriction Encourage patients to lay back rather than sit up during treatments. Frequent monitoring: symptoms, signs (15 minute vitals with set points for reducing BFRs and UFRs and delta changes for HR & BP); recognize the symptoms and signs of impending doom (including new onset cough, excessive yawning, dysphonia, ear fullness/ear popping pressure changes, HAs, n/v, cramping, MS and visual changes, etc); set max UFR and total fluid removal limits; individualized ticklers for patients with usual tolerance if < max UFR; increased time allowances as part of standing orders Eating during and after (EAT—eat after treatment) is encouraged to help reduce the harm of electrolyte and osmotic shifts With the lengthened time and decreased heparin approach, we usually administer mid-treatment saline infusion flush of (150 cc) especially if little intradialytic volume gained to ensure minimum ultrafiltration rate. Anticoagulation has not been a problem with longer runs (non-reuse) One size dialyzer: with longer times, we selected smaller dialyzer which may have been a factor that helped reduce symptoms Ultrafiltration profiling must be monitored closely: we discourage use other than linear to help prevent errors in execution and prevent exceeding UFR if sign offs occur Considerations for default 4 hour and standard dialysate bath approaches • • • • • • • • • • Prescriber caution for excessive diuresis in patients with RRF & UOP resulting in potential increased sodium levels, decreased Mag & K, and ICW-ECW shifts, which may worsen dialysis clinical intolerance. Patients may require added interdialytic water and/or intradialytic volume to improve therapy tolerance and meet minimum ultrafiltration requirements for machine and filter performance—reduce BFR, dialyzer size. Caution for ICW-ECW shifts with high glucose levels. Avoid larger dialyzers if able when time is increased (especially if BFR and DFR are ramped up) to help reduce rapid osmotic and electrolyte shifts—consider using dialyzer escalation protocols or single dialyzer facility use. Longer Tx duration may require lower bicarbonate, higher dialysate K and Mag (or liberalized dietary discretion and supplementation/eating especially just prior to dialysis), lower BFRs and Na; nutritional status, frailty, dialysis vintage RRF, and age, comorbid condition score, electrolytes, DM control, muscle mass and VoD should be considered Anticoagulation: take it slow with ramping up since it has not been problematic. Our average heparin dose is < 2000 units/treatment (no reuse) Comfort in chair: longer Tx times challenge patients; efforts to decrease discomfort using pillows under arms instead of arm extensions on chair may reduce pause therapy episodes including needle dislodgement; pillows behind head and roll pillows under ankles or knees while lying back in chair help with lower back complaints for some patients Engage patients and family in any way possible for their therapies. Track sign off, early termination reasons—AMA form. Require use of a calculator to help reduce errors Increased surveillance revealed more reported episodes of care with cramps and hypotension until plan fully implemented. Accurate trending over time including QoL perception, TTR, and clinical intolerance of therapy are important for PI. Lower sodium may result in less tolerance if other factors are not adjusted accordingly. Difficult challenges included convincing staff, patients and prescribers to avoid reducing time as Kt/V improved with the increased time on dialysis. Caution: rare opportunistic prescribers tried to advertise lower times and larger dialyzers to entice patients. We overcame those conflicts through collaboration with nearby ethical medical directors, and by directly communicating the safety reasons for increased time on dialysis with patients. Pause & Interrupted Troubles, Stop Alarms & Leaving Early Scenarios • Efforts to reduce inadequate and inefficient dialysis: reducing errors in set up; reducing dialysis catheter temporary accesses and access complications; reducing IMEs S^TOP: Safety at Top of the Hour RN Rounds Safety project Paul E. Miller, MD Identified need and details • • • • Missed opportunities to avert patient harm S^TOP Check List Escalation Procedures Systematic Safety Surveillance of entire station including patient and walk area environment every visit to station by any staff member— not just top of hour • Hemodynamic trending and proactive changes Findings • Improved clinical tolerance and less hypotensive episodes. Patients feel more secure with more focus on them. • Accountability with oversight is needed to make sure staff creep does not set in • Harm prevention strategies for some patients will increase leaving heavy occurrences and require extra therapies • Checklists are great. However, too much information overload distracts staff. The lists must be succinct, and prompt staff at the point of care to remind them of the critical thought processes. Our safety checks started out with longer lists to train staff akin to training children how to perform long division first. OASIS Systematic Dialysis Education Strategy • Overview and Options (transplant, home, advanced directives, etc) Access—(ADAPT) • • Support Services • Individual Responsibility—(Priority in Patient • Engagement Education) Systems Education and Safety (Nutrition, Na, K, BMD, volume, anemia, access care, fall prevention, cardiovascular, immunizations and other prevention strategies; Safety) (HO-i-PE) Home Options Improve Patient Experience with Dialysis There’s Hope at Home in Dialysis Paul E. Miller, MD Home Dialysis Success • In the beginning, we tried to expand home dialysis offerings. It was challenging. As staff ratios changed and expectations for excellence with all the projects expanded, we ramped up our efforts to initiate with PD or transition to home. It has been a wonderful experience promoting health, happiness, and independence at home giving more hope to patients on dialysis. The shifting towards home offset HD staffing ratio concerns and staff turnover problems that risked patient safety. ASURE-CARE: Assess Status Upon Return from Episodes of Care Mitigate harm caused by gaps in information sharing across the transitions of care and ensure readiness for safe outpatient care Paul E. Miller, MD Identified need and details • Admission of transient and other patients who were not stable or appropriate for outpatient care • Reduce re-hospitalization rates and information sharing gaps • Prevent missed antibiotic dosing in transition and prescription adjustments including anticoagulation and optimal volume status • All patients called to prescriber and medical director for review prior to admission—and prescriber upon first treatment for validation of treatment prescription • We have rigorous initial admission policy requirements. We needed to treat each return to facility with similar scrutiny for risk assessment and readiness to make sure we could meet mutually agreeable realistic goals of therapy. Effective gate keeper strategies were instituted and refined. Information Sharing • Each month, the big labs and a treatment sheet and encounter summary note are transmitted to key providers for continuity of care. Communication during transitions was improved by sending a treatment sheet with prescription, medications, and key caution in care ticklers to the areas of encounter at that time. Patients were educated to always call us at the time of a new prescription and remind us when presenting to the clinic for updates in care, encounters, etc. • If patients are admitted to a hospital, they are to call and ask the clinic to participate in the coordination of care. We coordinated with local emergency rooms to fax the encounter notes at the time of ER discharge. • IT has been great: Patient Portal is coming soon. For now, we encourage patients to be engaged and keep with them the updated information. SAFETY: Safety Assurances from Everyone Treating You Team training to consider the patient perspective Paul E. Miller, MD SAFETY: The Patient Perspective • All team members are taught that safety is everyone’s responsibility. Safety Assessments are everyone’s duty including social workers and dieticians—all eyes on the patient, station and surrounding environment. • Behavior Based Safety (BBS) principles are emphasized • Safety Assessments and Assurances from Everyone Treating You it is what we want patients perceiving for an improved sense of security, stronger trust in us • Hazard Identification, Risk Assessment and Risk Control • http://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/students/bey ond/Pages/hazidentify.aspx Safety Training • • • • • • Vitals every 15 minutes; specific direction regarding early recognition of impending doom including changes/trending of vitals suggesting hemodynamic collapse. Since the machines do not have adequate biofeedback reductions in ultrafiltration and BFR, we had to pay closer attention to manually address these situations to prevent ischemic harm to patients. Longer times on dialysis allowed us flexibility in reducing BFRs and sodium. Focus on task at hand: no longer were technicians allowed to do anything but focus on patients and be present on floor directly engaged with patients rather than performing non-direct patient care activities. We reduced distractions: distractions are taught as that which leads to lack of focus—which results in actions or inactions that kill. Adverse events, incidences, and near misses were reviewed. Revamped team safety training with safety checklists, safety rounds, and culture of safety philosophies. Alarm resetting limits and escalation taught. Caution-in-Care Ticklers added to each treatment sheet and carried over Accountability at all levels was enforced. Lab reviews required 6 month trending to mitigate missed signals of safety: medical director trained staff regarding subtle changes to monitor Problem Solving Strategies • Categories of safety failures along the path to patient add structure for team members on safety rounds when using Problem Solving Strategies • Hazard Risk Assessments • Failure Analysis for devices and processes • Event and fault tree analysis • 5 Whys and What If analysis • Root Cause Analysis • Medical director reviews and approves all devices, protocols, prn orders, processes, medications and supplies to help reduce errors where possible Guide for Medical Directors when selecting devices in dialysis • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Does it improve safety and quality? Does it mitigate extra human steps that are unfortunately required to make misaligned path-to-patient products and processes safer? Does it simplify the complexities that cause confusion and recurring safety breaches? Does it align with all the other moving parts along the continuum of path to patient? Does it support practical approaches that consistently achieve safe and quality care? Is there a good plan of roll out, reliable surveillance and support to ensure consistent safe use? How’s the manufacturer’s history of financial stability, training, retraining, reliability, integrity, response time, and service? Is the device FDA approved and does AAMI have any specific caveat guidance regarding use? What are the pros and cons of use? Is adequate training and ongoing support included? Has there been enough use for the glitches and bugs to have been worked out? How’s the device’s performance regarding downtime, recalls, reliability, warranty, maintenance, and support? What upgrades are not included in basic support plans? Is it cost effective? Does it support superior and safe care for patients? How does it differ from other devices in same class? How long are you locked-in regarding the use of proprietary accessories to the device? Are there other clinics in the region using the device, and what are their experiences with the device? If accessories to device are needed, what are the delivery costs and details (especially if no nearby facilities use device)? What unusual expertise is needed for maintenance and monitoring? What disinfection type and schedule, if any, are required? Are supply shortage risks for device accessories increased with no manufacturer competition? Distractions Result in Actions that Kill • Cellular phone and personal electronic device use • Watching television; smoking breaks • Staff aggregating at nurse’s station and away from floor (losing focus and gaining distance) • Speaking on phone while caring for patients • Doing anything else rather than direct patient care actions while patients are dialyzing including dialysis treatment sheet computer entry, preparing set ups for next shift, and educational modules • Idle time is dangerous for staff…they need to be directed for task completion; otherwise, attention failure will result • Not monitoring closely, resulting in failure to recognize early hemodynamic changes or signals—Focus Fatigue FLARES • We educated the staff to recognize impending doom, and act as flares for early escalation and intervention. • Focus (on the patient and the task at hand) • Look/Listen (look at patient and station--not just the access-- then hone in on the details; listen to patients as they breathe and as they speak including what they are saying with their words and expressions) • Ask/Acknowledge (ask how they feel, and acknowledge their needs and complaints and monitor for symptom/sign improvement and resolution) • Review/Record (review the prescription to ensure that it is being delivered as intended; review trending hemodynamics for safety parameters set by medical director and prescriber and record the review) • Escalate as appropriate (alarms, concerns, questions, etc) • Signal to patient with an empathetic kind smile; and if all ok a thumbs up; and sign document/electronic signature of safety rounds Recurring Safety Failures in the Acute Dialysis Realm • • • • • • • • Lack of communication, nephrology oversight, nephrologist medical director, appropriate procedures and following procedures Missing the signals of safety Optimal volume status—leaving heavy or new dry weight: not communicating with HD center Verbal prescriptions to non-dialysis nurses where errors in transcription and bidirectional communication occur Not validating prescription with MD at beginning of dialysis each session and not notifying prescriber for any problems occurring with the session or reminding at subsequent sessions to mitigate repeat failures Failure to use adequate infection control techniques and proper button hole techniques Insufficient dialysis Dialyzing patients in the extreme zones: severely elevated glucose levels to “normalize” the labs not considering ICW-ECW shifts and status; severe acidosis not considering total body electrolytes, effects of rapid acidosis correction, & dialysate Rx selection STOP-BLEED Steps to overcome patient blood loss episodes emerging from dialysis Paul E. Miller, MD Blood loss risks and considerations • • • • • • • • • • Thrombocytopenia—some clinics do not check platelets often and miss the rare, but serious condition Significant Bruising and Oozing: missing the opportunity to limit anticoagulation Catheter ports: > 1,000 units/mL heparin increases risks of problematic systemic exposure complications; during catheter placement and other surgical procedures or encounters, anesthesia or other personnel commonly use the catheter and push prior to aspiration and instill higher concentration of heparin for catheter locks Failure to monitor reasons for oral anticoagulation and desired INR levels Catheters and problematic AV access resulting in recirculation and early system clotting Large bore dialysis cannulation needles; increased angle of needle to skin Lost blood in circuits: recirculating too long without returning blood and not timely recognizing or escalating for impending system clotting—(e.g., repeat alarms resetting; too much time spent repositioning needles or withdrawing air bubbles from chamber; incorrect setups with excessive air introduced in dialyzer and early clotting of system; interrupted or disconnected for other reasons such as bathroom visits) Dialyzing patients on same day as procedures including catheter insertion Leg grafts and other accesses that are not held long enough post needle removal: when patients advance pressure by using limbs, bleeding may initiate and not be recognized until much later especially if leakage is underneath the skin. Chest or necklace grafts should be monitored for bleeding risks closely. Catheters: non-tunneled or non-secured catheters and thrombolytic catheter lock dwells Blood Loss Mitigation Strategies • Reduce Heparin (catheter concentration and intradialytic): heparin dosing reviewed each month; above 5,000 units/treatment must be approved by medical director • Appropriate button hole technique • Observe bleeding tendencies • Review appropriateness of multiple blood thinner co-administration • Avoid: unnecessary large bore cannulation needles, unstable positioning of access arms & taping techniques, and inexperienced stickers for new or tenuous accesses • Avoid catheters and avoid dialysis on day of procedures • Return blood early rather than repeat resetting of alarms on machines— early escalation • Educate and practice with patients regarding what to do for blood loss episodes including stopping dialysis, holding sites, & post dialysis at home Blood Loss Mitigation Considerations • • • • • • • • • Too much heparin initiated from traditional beliefs and practices regarding clearances and heparin (reuse/nonreuse) Heparin not timely reduced when patients are receiving other meds such as coumadin, antiplatelet or other "blood thinners” Not reduced when patient changes from catheter to permanent access Not reduced when patients have falls, procedures, hematomas or other predisposing events or conditions Inappropriate heparin ramping without physician input as a result of early clotting of filters related to access recirculation or other access problems; heparin dose increases and rarely decreases Heparin dosing by nursing staff without safe boundaries, evidence-based approaches, or quality assurance monitoring Heparin is not adjusted for platelet count and easy bruising conditions, slow hemostasis conditions, or for patients with GI or other bleeding risks Recognizing clues that suggest acute blood loss for early mitigation efforts: ESA dose above usual for 6 month average for patient; sudden drop in hemoglobin; or new onset dark stools Blood thinner use that is contraindicated for kidney failure patients Securing Initial, Repositioned, and Exiting Needles and other tips • • • • • • • • Observe for problems with tape not adhering or needle backing out: patient must be monitored closely—tracking and recording efforts during remaining treatment Warning signs must be escalated & problems safely and confidently resolved (not just over 1-2 minutes) Efforts must be made to clear the surface of skin of any substance that is preventing the tape from adequately adhering or interfering with needle positioning such as clothes or obstacles pulling on the needle, lines, or tape. Once tape is removed, new tape for securing is required. BFR must be reduced below 300 until the close monitoring is done and a gradual ramping to prescribed goal is done in a safe and closely monitored manner over the next 1/2 hour. If a needle has to be repositioned for backing out, escalate to nurse. Caution with positioning of needles with larger angles to skin for deep tracking accesses and large limbs: these are challenging to secure and may offer greater risk of dislodgement and access wall injury—escalate for consideration for access revision and longer needle use. No patient can hide their access at any time during dialysis. Two needle sites simultaneously held by patients can lead to blood loss episodes. Two clamps at one time can be unsafe especially for patients with visual impairment, frail, physically or mentally challenged (who may not be suitable for holding or monitoring their own sticks). Clamps may present problems, and may not be used safely for certain challenged patients. • Experiencing a needle dislodgement leaves a lasting impression like a red SIREN screaming in the night. • • • Resources: http://www.edtnaerca.org/pdf/home/VNDpaper.pdf Van Waeleghem J.P., Chamney M., Lindley E.J., Pancírová J. (2008). Venous needle dislodgement: how to minimise the risks. Journal of Renal Care 34(4), 163-168. • Buoys, Boundaries, and Triggers in Dialysis Safety project: safe limits and escalation protocols Paul E. Miller, MD Prompts and Reminders • Placards laminated near station for rapid view of parameters and escalation algorithms • Prescribing limits • Lab limits (parameters and delta changes), and other aspects of care—boundaries and guides for escalation • Simple question or image poster prompt at the scale for patients and staff Angioaccess Intervention Management: AIM higher ADAPT: Approaching Dialysis—Access Planning and Timing Access management philosophies for established and new patients Paul E. Miller, MD Race-to-Place • Efforts to reduce HD catheter exposure time that focus on shortening the time to effective permanent access placement. • Asking vascular surgeons to consider placing patients on “stand-by” for canceled appointments and surgeries to reduce time to placement (often, surgeons feel no rush to place AV accesses if patients are dialyzing successfully with HD catheters; most surgeons do not perceive the time of exposure failure risk of HD catheters) Avoid Vancomycin Overuse in Dialysis: AVOiD Reduce antibiotic use in dialysis Paul E. Miller, MD Identified need and details • Vancomycin use was problematic. • Prescribed on whims; procedural MDs wanted the clinics to deliver Vancomycin for everything including every post access intervention • All Vancomycin prescriptions now have to be approved by medical director. Oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is available for iffy circumstances until next day review by MD if appropriate. Some iffy circumstances include post dialysis access placement with warm, red and swollen limbs or erythema surrounding exit site of dialysis catheter • As a result of low catheter rates (and avoidance of chronic infected limb or chronic infected device antibiotic incenter treatment), we go months without Vancomycin antibiotic administration. Reducing Buttonhole Infections Extra Step to Disinfect and Protect Paul E. Miller, MD Identified need and details • Increased concern over infections • Extra steps to disinfect and protect have proven very effective at preventing infections • Button hole procedures have been very beneficial in our clinics with reduced infiltrations, blood loss episodes, discomfort and intolerance. Managing Acidosis in Dialysis: MAiD Easy Safety project using oral bicarbonate and setting dialysis alkali dosing limits Paul E. Miller, MD Identified need, details and outcomes • Higher machine settings for bicarbonate were not achieving quality and safety goals. There was often a mismatch of executed therapy and intended prescription. • Lab preparation techniques and testing were problematic • We initiated oral bicarbonate therapy and set limits for maximum machine setting for bicarbonate. The oral bicarbonate therapy is well tolerated and helps reduce hyperkalemia episodes. Tale at the Scale Listening to each patient’s story Paul E. Miller, MD Identified need and details • Tell your tale at the scale is an educational promotion to patients and staff to help reduce information sharing gaps—information that helps reduce safety failures such as missing falls and blood loss episodes, patient intolerance of dialysis, preferences and concerns, medication changes, contagious conditions, medical encounters, and symptoms. Dose After Dialysis Capturing Events and Responding to Recovery after Dialysis Paul E. Miller, MD Identified need and details • Dose after dialysis started as a reminder to capture experiences and events of patients during and after dialysis. It later migrated into an educational reminder to monitor the carry-over effects or hangover after dialysis—the perceptions of patients regarding time to recovery to determine if their dosing of dialysis needed improvement. With lengthened times, focus on maintaining near normalcy, nutritional support, reduced UFRs, and overall efforts to reduce shock and awe of therapies, time to recovery (TTR) has improved. Be Smart, Do Your Part Health Begins at Home—Priority in Patient Engagement Education Paul E. Miller, MD Identified need and details • Patient responsibility in care: patients can improve health and reduce safety complications—daily stool softeners, oral bicarbonate and dietary discretion reduce risk of hyperkalemia and improve safety in uremic acidosis management. Avoiding sodium and aluminum are emphasized. We educate that sodium is not just what patients pour, but what’s sought & bought from the store or brought through their door. • Fall prevention, dental and foot care • Access care: placement, monitoring and cleaning • Medication adherence, preventive care, immunizations • Patient engagement reduces errors & improves satisfaction. MD emphasizes the patient role in care and safety: cognizant of prescriptions, machine settings, processes; alert for changes and monitor as neighborhood watch for others on dialysis. • Other areas of compliance (TT, skips, sign offs) Proaction for PD Satisfaction: Backup HD for PD • Intermittent backup HD runs reduced hospitalizations, improved volume status, prolonged home therapy options for patients, and improved QoL. Suggested resources for stewards of safety that should be readily available – sample outpatient dialysis clinic prescription template with safe prescribing parameters, standing & prn orders, boundaries and limits – sample P&Ps – sample e-alerts notification, parameters and triggers – sample list of commonly missed signals of safety in dialysis – sample: safety lists, escalation tools, and reporting process – sample: progress note and encounter form with prepopulated sections – Educational podcasts for topics such as adverse events & near misses – Discharge Orders for Transition Safety—(Connecting the Dots) – Validating Acute Prescription Orders Unburdening RN in Acute Dialysis – Practical Prescribing Tools and Pearls in Dialysis: A guide for the prescriber and nurse for acute and chronic settings – Hospital emergency room, admission and prn Sample Order Sets – Inpatient Dialysis Sample Order Set Validating Acute Prescription Orders Unburdening RN in Acute Dialysis • Call to prescriber at each presentation for dialysis after patient assessment. For ARF patients, structured assessment was instituted to reduce risks of compromising renal recovery and prolonging unnecessary exposure to central venous lines—this was especially important for the circumstances where prescribers were unfamiliar with patients • Minimum prescription validation: duration; access and specifics— BFR, needle size and type or catheter lock details including concentration of heparin or other; anticoagulation type, amount if any and frequency; flushes; total removal volume, UF and other profiling, and maximum rate—max UFR; parameters for calling MD; specifics regarding use of any BVM devices, prn medications, oxygen, or cardiac monitoring; dialyzer size; DFR; dialysate temperature; type of dialysate: electrolytes—sodium, magnesium, potassium, bicarbonate; medication administration; treatment sheet faxing to outpatient center if appropriate Discharge Orders for Transition Safety • • • Correspond with outpatient facility through phone and fax for updating health information. Nephrologist updating of patient status must be communicated with outpatient dialysis Fax all labs, imaging reports, operative reports, hemodynamic monitoring reports (graphics), consults, H&Ps, D/C summaries, transfusion histories, culture reports, last two dialysis treatment sheets, last nephrology progress notes, d/c medication reconciliation, d/c instructions and appointments, d/c orders Weigh patient after each dialysis (standing if able) and fax the last weight upon discharge and last post dialysis weight if different If prescribed Coumadin or coumarin, notify patient and center of next lab draw and who is responsible for monitoring outpatient INR/PT; and reason for use, duration of therapy, and desired goals of therapy Notify outpatient facility of last HD treatment to reduce skip treatments during transitions with consideration for next day dialysis If a dialysis catheter is placed, outpatient vascular access surgical or PD appointment must be made; no temporary non-tunneled dialysis catheters are accepted into facilities If transitioning to NH, SNIF, Rehab, or LTAC, notify nephrologist and facility upon admission to those facilities to assist with continuity of care Provide patient with contact information for on-call nephrology need Notify outpatient dialysis facility of need for antibiotics, course of therapy, and reasons. • • • Suggested Resources: Care Transitions and Network 4 Resources “Hospital to Dialysis Unit Transfer Summary” • • • • • • Suggested Resources • Care Transitions and Network 4 Resources • “Hospital to Dialysis Unit Transfer Summary” • Tools/resources for hospital discharge planners within the Fistula First tools (sect L) • http://www.network13.org/QI_Reports.php Suggested Resources • Method to Assess Treatment Choices for Home Dialysis (MATCH-D) • www.homedialysis.org/match-d • CDC Dialysis Checklists • 5 Diamond Patient Safety Program Suggested Reading • • • • JANUARY 31, 2001 Collaborative Leadership for ESRD Patient Safety Phase 1 Report of the National Patient Safety Consensus for the Community of Stakeholders in End Stage Renal Disease The Role of Medical Directors in Dialysis Facilities: Series Editor : Robert A. Gutman: The Dialysis Medical Director’s Role in Quality and Safety • Alan S Kliger The dialysis medical director's role in quality and safety. Seminars in dialysis 2007;20(3):261-4. Patient safety in the dialysis facility. Blood purification 2006;24(1):1921. • Maintaining Safety in the Dialysis Facility • CJASN November 2014 CJN.08960914Patient and facility safety in hemodialysis: opportunities and strategies to develop a culture of safety. Renee Garrick, Alan Kliger, Beth Stefanchi • Suggested Resources • AHRQ Safety Program for End-Stage Renal Disease Facilities – Toolkit • ESRD Toolkit Modules: • Creating a Culture of Safety • Clinical Care • Using Checklists and Audit Tools • Patient and Family Engagement Miscellaneous comments regarding safety in dialysis • • • • • • • • • • • • • No poka-yoke device or fail-safe process in dialysis; dialysis is not a machine, it is a process Not always about P&P, manufacturer’s mechanical faux pas or a pending technological fix Good judgment, less risks, safety threshold parameters & escalation protocols, & simplifying the process from path to patient Caring attitudes, behavioral routines, attention to detail—prevention strategies Accountability at all stages from path to patient and at all encounters Training safety and process improvement concepts including pattern recognition Avoiding knee-jerk algorithms that react with regurgitation; setting limits on certain prescribing aspects; requiring escalation and validation protocols Recognizing ominous signals & changes in status that suggest impending doom can only mitigate safety failures if appropriate responses to these signals of safety (patient SOS signals) are timely executed and followed through Engaging entire team including patients is essential to achieve enduring success Partnering with lab provider and IT for meaningful adjunct tools for mitigating safety failures Select practical approaches that prevent patient harm while using therapies that always pose risks Measuring safety in dialysis can be challenging—especially if harm is not understood, events are not captured, reported, accurately characterized, and appropriately depicted using visually friendly trending formats. Monitoring intolerance to dialysis using carefully selected surrogate markers including patient perception is important for safety teams. There is no universally adopted safety grading scale or system in dialysis for safety scoring of each dialysis session; therefore, an all-hazards harm prevention strategy must guide the stewards of safety. Miscellaneous comments regarding safety in dialysis • • • • • • • • • • • • The timeline for safety progress in dialysis is populated with many innovations. Despite the advances, preventable safety failures echo as recurring themes because traditional reactive philosophies undermine safety-first proactive efforts. Effective safety programs require medical director engagement and prescriber, patient and entire team buy-in. Acute programs that are not supervised by quality nephrologist medical directors compromise the continuum of care and safety efforts of the outpatient dialysis programs. Holistic approaches are necessary for optimal care. Patient or prescriber refusal should not prevent future safety discussions using different approaches P&Ps are like disaster plans and need to be routinely practiced, critiqued, and updated Expecting nurses to consistently execute complex Rx’s and juggle disparate clinic standing and prn orders is unrealistic. Such complex care, if necessary, is best delivered at home or in hospital settings with one-on-one focus Categories of safety failures are well described in literature. The industry, however, has not adequately shared problemsolving strategies for some of the most preventable repeat patient harm events. A broadened focus on the culture of safety presents opportunities for the industry to share experiences, practical solutions, working examples of algorithms, QAPI projects, and P&Ps in an effort to advance the safety discussion from theory to practice for every dialysis realm. Signals of safety in dialysis are commonly missed. Failure to timely recognize and respond risks harm to patients. Failure of pattern recognition with small clinic numbers may preclude effective QIP for certain situations. Expanded reporting of near miss and hard hit occurrences is important. Few internal safety registries exist which could offer practical insights from the collective experiences. Advanced safety certification could be part of credentialing processes for clinic prescribers and medical directors A safety scoring mechanism or scale for each dialysis session is needed. If the 5 star ratings program were safety based, there would be less fluff, and a lot more meaningful stuff aiding the dialysis stewards of safety. After all, how meaningful are measurements of dialysis quality and success without consideration for patient safety, clinical tolerance and intolerance? Safety in Dialysis “It Don’t Come Easy” Richard Starkey (Ringo Starr) and George Harrison