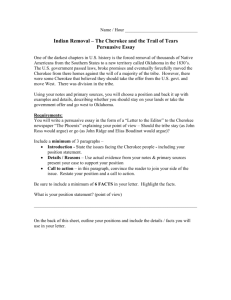

Trail of Tears Required Readings

advertisement

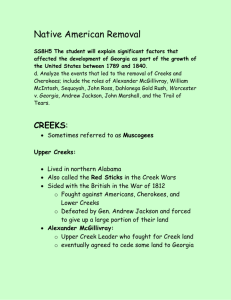

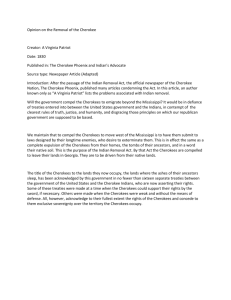

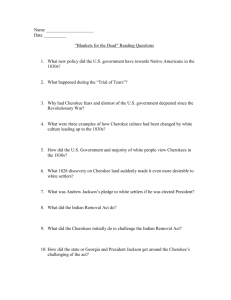

The Trail of the Tears - Required Readings In 1838, the Cherokee Nation was removed from their lands in the Southeastern United States to the Indian Territory (present day Oklahoma) in the Western United States, which resulted in the deaths of approximately 4,000 Cherokees. In the Cherokee language, the event is called Nunna daul Isunyi—“the Trail Where They Cried.” The Cherokee Trail of Tears resulted from the enforcement of the Treaty of New Echota, an agreement signed by Major Ridge and his Cherokee negotiation party under the provisions of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 which exchanged Native American land in the East for lands west of the Mississippi River, but which was never accepted by the elected tribal leader, Chief John Ross, or a majority of his Cherokee people. Tensions between Georgia and the Cherokee Nation were brought to a crisis by the discovery of gold in Georgia, in 1829, resulting in the Georgia Gold Rush, the first gold rush in U.S. history. Hopeful gold speculators began trespassing on Cherokee lands, and pressure began to mount on the Georgia government to remove the Cherokee under the provision of the Indian Removal Act of 1830. . When Georgia moved to extend state laws over Cherokee tribal lands in 1830, Chief John Ross plead the Cherokee case to the U.S. Supreme Court. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), the Marshall court ruled that the Cherokees were not a sovereign and independent nation, and therefore refused to hear the case. However, in Worcester v. State of Georgia (1832), the Court ruled that Georgia could not impose laws in Cherokee territory, since only the national government — not state governments — had authority in Indian affairs. Upset with the Marshall Court’s ruling, President Jackson had no desire to use the power of the national government to protect the Cherokees from Georgia, especially since he was already entangled with states’ rights issues in what became known as the nullification crisis. With the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the U.S. Congress had given Jackson authority to negotiate removal treaties, exchanging Indian land in the East for land west of the Mississippi River. Jackson used the dispute with Georgia to put pressure on the Cherokees to sign a removal treaty. Despite Chief John Ross and the majority of the Cherokee peoples’ objections, the Treaty of New Echota was passed by Congress by a single vote, and signed into law by President Andrew Jackson. Backed by this treaty, General Winfield Scott with an armed force of 7,000 made up of regular army and militia from Georgia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Alabama, forced about 13,000 Cherokees into concentration camps at the U.S. Indian Agency near Cleveland, Tennessee before forcing them to march West. Most of the deaths associated with the Trail of Tears occurred from disease, starvation and cold in these camps. While in the camps their homes were burned and their property destroyed and plundered. Farms belonging to the Cherokees for generations were won by white settlers in a lottery. In the winter of 1838 the Cherokee began the thousand mile march with scant clothing and most on foot without shoes or moccasins. The march began in Red Clay, Tennessee, the location of the last Eastern capital of the Cherokee Nation. The Cherokee were given used blankets from a hospital in Tennessee where an epidemic of small pox had broken out. Because of the diseases, the Indians were not allowed to go into any towns or villages along the way; many times this meant traveling much farther to go around them. After crossing Tennessee and Kentucky, they arrived in Southern Illinois about the 3rd of December, 1838. Here the starving Indians were charged a dollar a head to cross the river on "Berry's Ferry" which typically charged twelve cents. They were not allowed passage until the ferry had serviced all others wishing to cross and were forced to take shelter under "Mantle Rock," a shelter bluff on the Kentucky side. Many died huddled together at Mantle Rock waiting to cross. Several Cherokee were murdered by locals. The killers filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Government through the courthouse in Vienna, suing the government for $35 a head to bury the murdered Cherokee. Removed Cherokees initially settled near Tahlequah, Oklahoma. When signing the Treaty of New Echota, Major Ridge had said "I have signed my death warrant." Now the resulting political turmoil led to the executions of Major Ridge, John Ridge, and Elias Boudinot; of the leaders of the Treaty Party, only Stand Watie escaped death. Samuel’s Memory “Samuel’ s Memory” is the recollection of a Cherokee Indian named Samuel Cloud who was forced, along with his family, to make the difficult journey to Indian Territory known as the Trail of Tears. Samuel turned nine years old on the Trail of Tears and told his story to his great-great grandson, Michael Rutledge, many years later. Michael, who is a citizen of the Cherokee nation and was a law student at Arizona State University, included his greatgreat grandfather’ s story in a paper titled “Forgiveness in the Age of Forgetfulness”. It is Spring. The leaves are on the trees. I am playing with my friends when white men in uniforms ride up to our home. My mother calls me. I can tell by her voice that something is wrong. Some of the men ride off. My mother tells me to gather my things, but the men don't allow us time to get anything. They enter our home and begin knocking over pottery and looking into everything. My mother and I are taken by several men to where their horses are and are held there at gun point. The men who rode off return with my father, Elijah. They have taken his rifle and he is walking toward us.... They lead us to a stockade. They herd us into this pen like we are cattle. No one was given time to gather any possessions. The nights are still cold in the mountains and we do not have enough blankets to go around. My mother holds me at night to keep me warm. That is the only time I feel safe. I feel her pull me to her tightly. I feel her warm breath in my hair. I feel her softness as I fall asleep at night.... It is now Fall. It seems like forever since I was clean. The stockade is nothing but mud. In the morning it is stiff with frost. By mid-afternoon, it is soft and we are all covered in it. The soldiers suddenly tell us we are to follow them. We are led out of the stockade. The guards all have guns and are watching us closely. We walk. My mother keeps me close to her. I am allowed to walk with my uncle or an aunt, occasionally. We walk across the frozen earth. Nothing seems right anymore. The cold seeps through my clothes. I wish I had my blanket. I remember last winter I had a blanket, when I was warm. I don't feel like I'll ever be warm again. I remember my father's smile. It seems like so long ago.... When I went to sleep last night, my mother was hot and coughing worse than usual. When I woke up, she was cold. I tried to wake her up, but she lay there. The soft warmth she once was, she is no more. I kept touching her, as hot tears stream down my face. She couldn't leave me. She wouldn't leave me. I hear myself call her name, softly, then louder. She does not answer. My aunt and uncle come over to me to see what is wrong. My aunt looks at my mother. My uncle pulls me from her. My aunt begins to wail. I will never forget that wail. I did not understand when my father died. My mother's death I do not understand, but I suddenly know that I am alone. My clan will take care of me, but I will be forever denied her warmth, the soft fingers in my hair, her gentle breath as we slept. I am alone. I want to cry. I want to scream in rage. I can do nothing.... I know what it is to hate. I hate those white soldiers who took us from our home. I hate the soldiers who make us keep walking through the snow and ice toward this new home that none of us ever wanted. I hate the people who killed my father and mother. I hate the white people who lined the roads in their woolen clothes that kept them warm, watching us pass. None of those white people are here to say they are sorry that I am alone. None of them care about me or my people. All they ever saw was the color of our skin. All I see is the color of theirs and I hate them. Junaluska War With The Creeks Junaluska, the Cherokee who saved Andrew Jackson’s life and made him a national hero, lived to regret it. Born in the North Carolina mountains around 1776, he made his name and his fame among his own people in the War of 1812 when the mighty tribe of Creek Indians allied themselves with the British against the United States. At the start of the Creek War, Junaluska recruited some 800 Cherokee warriors to go to the aid of Andrew Jackson in northern Alabama. Joined by reinforcements from Tennessee, including more Cherokee, the Cherokee spent the early months of 1814 performing duties in the rear, while Jackson and his Tennessee militia moved like a scythe through the Creek towns. However, that March word came that the Creek Indians were massed behind fortifications at Horseshoe Bend. Jackson, with an army of 2,000 men, including 500 Cherokee led by Junaluska, set out for the Bend, 70 miles away. There, the Tallapoosa River made a bend that enclosed 100 acres in a narrow peninsula opening to the north. On the lower side was an island in the river. Across the neck of the peninsula the Creek had built a strong breastwork of logs and hidden dozens of canoes for use if retreat became necessary. Storming The Fort The fort was defended by 1,000 warriors. There also were 300 women and children. As cannon fire bombarded the fort, the Cherokee crossed the river three miles below and surrounded the bend to block the Creek escape route. They took position where the Creek fort was separated from them by water. The battle raged throughout the morning. There were dead and wounded on both sides. Among the frontiersmen fighting for Jackson that day were Sam Houston & Davy Crockett. Saving Jackson’s Life And His Reputation A few prisoners were brought in, and while officers were attempting to question them in the presence of Jackson, one broke loose, snatched up a knife, and lunged for the general. Junaluska, who had seen the move, responded quickly, sticking out a foot and tripping the Creek warrior, saving Jackson’s life. As the battle wore on, Junaluska conceived a brilliant plan. Without notifying Jackson, he gathered a dozen Cherokees, sneaked to the river’s edge behind the fort, plunged into the water, and swam over to where the Creek canoes were moored. Junaluska and his braves freed the canoes and maneuvered them to the opposite bank where other Cherokee warriors piled into them and, under cover of a steady fire from their own companions, returned to the opposite bank, thus breaching Creek defenses. When more than half the Creeks lay dead, the rest turned and plunged into the river, only to find the banks on the opposite side lined with blazing guns and escape cut off in every direction. Of the 1,300 Creeks inside the stockade, including women and children, not more than 20 escaped. Of 300 prisoners, only three were men. Two weeks after the decisive battle, Billy Weatherford, the greatest of the Creek chiefs, surrendered to Jackson, turning the general into a national hero. Another Promise Broken When the battle of Horseshoe Bend was over, Jackson is reported to have told Junaluska: “As long as the sun shines and the grass grows, there shall be friendship between us, and the feet of the Cherokee shall be toward the east.” In a few short years Junaluska would have occasion to recall those words with bitterness. When the great removal of the Cherokee began, Junaluska said: “If I had known that Jackson would drive us from our homes, I would have killed him that day at the Horseshoe.” The Great Chief Returns Junaluska was among the Cherokee removed to the West. But he returned to the mountains of his birth in 1842, walking all the way from what is now Oklahoma. And when he returned, the state of North Carolina stepped in and recognized the debt that America owed him. By a special act of the state legislature in 1847, North Carolina conferred upon him the right of citizenship and granted him a tract of land at what is now Robbinsville, in Graham County. Junaluska died in 1858 and was buried on a hill above the town where, in 1910, the Daughters of the American Revolution erected a monument to his memory. A Tribute To Junaluska The script on the bronze plaque, bolted to a great hunk of native stone, says in part: “Here lie the bodies of the Cherokee Chief, Junaluska, and Nicie, his wife. Together with his warriors he saved the life of General Jackson at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, and for his bravery and faithfulness North Carolina made him a citizen and gave him land in Graham County.” An organization known as “Junaluska’s Friends” was recently organized, and restored the Junaluska grave site. Their work will be primarily devoted to keeping alive the memory of this Chief. Major Ridge (1771-1839) Major Ridge, also known as Ganundalegi meaning "The Man Who Walks On The Mountain Top", was a Cherokee warrior, leader, and principal signatory of the controversial Treaty of New Echota of 1836, which forced the remaining Cherokee inhabiting tribal lands in the southeastern United States to relocate to the Indian Territory. His signing of the treaty led directly to both the Trail of Tears and his own death —by Cherokee Blood Law (assassination) —in 1839. Ridge was born into the Deer clan in the Cherokee town of 1771, along the Hiwassee River (an area later part of Tennessee). Ridge's maternal grandfather was a Highland Scot; thus Ridge was 3/4 Cherokee by ancestry, and one of the many Cherokees of his time with partial European (especially Scottish) heritage. Ridge acquired the title "Major" in 1814, during his service leading Cherokees alongside General Andrew Jackson at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend during the Creek War. He also joined Jackson in the First Seminole War in 1818, leading Cherokees against the Seminole Indians. After the war, Ridge became a wealthy planter and slave owner of African Americans. Ridge was part of the Cherokee delegation sent to Washington to protest the illegal annexation by the State of Georgia of that part of the Cherokee Nation which lay within its territory after the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that Georgia's unilateral extension of its laws over Cherokee territory was illegal and unconstitutional in Worcester v. Georgia. Previously one of the most vehement opponents of removal, Ridge reluctantly switched his support after a conversation with President Andrew Jackson in which the latter informed the former he had no intention of enforcing the Supreme Court's decision. After that conversation, Ridge became one of the more zealous leaders of the "Treaty party," a group that advocated removal of the Cherokee Indians to the west as the only way to preserve the Cherokee Nation rather than attempting to retain Cherokee land illegally annexed by Georgia. John knew theirs was a minority view, and that the majority of Cherokees at present sided with Principal Chief John Ross, who hoped to reach a settlement allowing the Cherokee to stay in the east, but he hoped to bring the Nation over to what he saw as the only way out of the Nation's dilemma. Ridge was one of the signers of the Treaty of New Echota, but only after the treaty had reached Washington City, D.C., where he, son John Ridge, and Elias Boudinot were part of the National Council's latest delegation, headed by John Ross, attempting to negotiate staying in the east. Since the treaty surrendered all Cherokee land east of the Mississippi River and against their wishes, Ridge was regarded as a traitor by the Ross faction known as the National Party. Although the treaty was possibly illegitimate, it was ratified by the United States Senate and Andrew Jackson used it to justify the Cherokee removal now known as the Trail of Tears. The treaty allowed for those Cherokees who wished to remain in the east to do so and become citizens of the states where they resided, but this provision was ignored during the removal. On June 22, 1839, Ridge, along with his son and Boudinot (who both had also signed the Treaty of New Echota), were assassinated by pro-Ross partisans (there has never been any indication Ross himself knew of the plot in advance). Major Ridge was stabbed 48 times, had his chest jumped up and down upon, and was kicked repeatedly by the 25 members of Ross' faction in front of his family members. Chief John Ross (1790-1866) John Ross, also known as Guwisguwi (a mythological or rare migratory bird), was Principal Chief of the Cherokee Native American Nation from 1828-1866. Described as the Moses of his people, Ross led the Cherokee Nation through tumultuous years of development, relocation to Oklahoma, and the American Civil War. Ross was born in 1790 in Turkeytown, Alabama to Mollie McDonald, of mixed-race Cherokee and Scots ancestry, and Daniel Ross, a Scots immigrant trader. Despite Daniel's willingness to allow his son to participate in some Cherokee customs, the elder Ross was determined that John also receive a rigorous classical education. After being educated at home, Ross pursued higher studies at an academy in South West Point, Tennessee. Having been educated almost exclusively in English by white men, Ross was a poor speaker of the Cherokee language. Nevertheless, his bi-cultural background would later allow him to represent the Cherokee to the United States government. In the changing environment which Cherokees encountered in the 19th century, they needed the political skills and English language which Ross had developed. The majority of Cherokees ardently supported Ross, electing him as their principal chief in every election from 1828 through 1860. The Council selected Ross because they perceived him to have the diplomatic skill necessary to rebuff US requests to cede Cherokee lands. In this task, Ross did not disappoint the Council. Ross argued two cases on behalf of the Cherokee: Cherokee Nation v. Georgia and Worcester v. Georgia. In the Cherokee Nation v. Georgia decision, Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that the Cherokees were a "domestic dependent sovereignty" and as such did not have the right as a nation state to sue Georgia. The court later expanded on this position in Worcester v. Georgia, ruling that Georgia could not extend its laws into Cherokee lands. It was not because they were fully sovereign, however, but because they were a domestic dependent sovereignty. As such the court ruled the Cherokee were dependent not on the state of Georgia, but on the United States. According to the series of rulings, Georgia could not extend its laws because that was a power in essence reserved to the federal government. The Cherokee were considered sovereign enough to legally resist the government of Georgia, and were encouraged to do so. The series of decisions embarrassed Jackson politically, as Whigs attempted to use the issue in the 1832 election. The Supreme Court’s rulings precipitated a split within the Cherokee leadership as John Ridge and Elias Boudinot began to doubt Ross' leadership. In February 1833, Ridge wrote Ross advocating that the delegation dispatched to Washington that month should begin removal negotiations with Jackson. However, Ridge and Ross did not have irreconcilable worldviews; neither believed that the Cherokee could fend off Georgia’s takeover of Cherokee land. Although Ridge and Ross agreed on this point, they clashed about how best to serve the Cherokee Nation. In this environment, Ross led a delegation to Washington in March 1834 to try to negotiate alternatives to removal. Ross' strategy was to prolong negotiations on removal indefinitely. He hoped to wear down Jackson's opposition to a treaty that did not require Cherokee removal. But, Ross' strategy was flawed because it was susceptible to the United States' making a treaty with a minority faction. On May 29, 1834, Ross received word from John H. Eaton, that a new delegation, including Major Ridge, John Ridge, Elias Boudinot, and Ross' younger brother Andrew, collectively called the Ridge Party, had arrived in Washington with the goal of signing a treaty of removal. The two sides attempted reconciliation, but by October 1834 still had not come to an agreement. In January 1835 the factions were again in W ashington. Pressured by the presence of the Ridge Party, Ross agreed on February 25, 1835, to exchange all Cherokee lands east of the Mississippi for land west of the Mississippi and 20 million dollars. But, he made it contingent on the General Council's accepting the terms. Lewis Cass, Secretary of War, believing that this was yet another ploy to delay action on removal for an additional year, threatened to sign the treaty with John Ridge. On December 29, 1835, the Ridge Party signed the removal treaty with the U.S., although this action was against the will of the majority of Cherokees. Ross unsuccessfully lobbied against enforcement of the treaty. Those Cherokees who did not emigrate to the Indian Territory by 1838 were forced to do so by General Winfield Scott. This forced removal came to be known as the "Trail of Tears.” Accepting defeat, Ross convinced General Scott to allow him to supervise much of the removal process. On the Trail of Tears, Ross lost his wife Quatie, a full-blooded Cherokee woman of whom little is known. She died shortly before reaching Little Rock on the Arkansas River. Ross later married again, to Mary Brian Stapler.