Arlington_House

advertisement

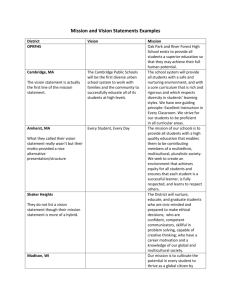

Running head: ARLINGTON HOUSE: FROM CUSTIS-LEE MANSION TO ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY Arlington House: From Custis-Lee Mansion to Arlington National Cemetery Audra Faust University of Montevallo 1 ARLINGTON HOUSE: FROM CUSTIS-LEE MANSION TO ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY 2 On a spring afternoon in May of 1861, a young Union officer rushed to a mansion sitting on a hill overlooking the Potomac River. “You must pack up all you value immediately and send it off in the morning,” Lieutenant Orton Williams, private secretary to Union Army General in Chief Winfield Scott, told his cousin Mary Custis Lee, wife of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. Working in Scott’s office, Williams had heard of the Union Army plans to seize Arlington, and so, Mrs. Lee supervised the frantic packing that began. Some of the 196 family slaves crated George Washington’s papers, G.W.P. Custis’ belongings and Robert E. Lee’s files. In a letter to her daughter Mrs. Lee wrote, “I fear that this will be the scene of conflict and my beautiful home endeared by a thousand associations may become a field of carnage” (Poole, 2009). Little did she know, her fear would become true and her home would become the final resting spot for soldiers from every American war. The story of Arlington begins in 1607 with the colonization of Virginia. The London Company, a joint stock company by the proprietary Charter of 1606, established the Colony of Virginia and named it Jamestown after King James I (Cooper & Terrill, 2009). Christopher Newport founded Jamestown in May of 1607 (Cooper & Terrill, 2009). The 105 original settlers dwindled down to 38 during their first winter (Cooper & Terrill, 2009). The colonists faced many obstacles, such as: a strong Powhatan tribe, disease, lack of food and supplies and lack of work ethic (Cooper & Terrill, 2009). In 1608, Captain John Smith took over leadership of the colony (Cooper & Terrill, 2009). Cooper and Terrill explain in their book, The American South, “During Smith’s year as president of the council he organized the colonists for work” (2009). ARLINGTON HOUSE: FROM CUSTIS-LEE MANSION TO ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY His motto of if a man does not work he does not eat greatly helped the shortage of labor within the colony (Cooper & Terrill, 2009). According to Cooper and Terrill, “When Smith left the colony, he had not guaranteed success but he had staved off disaster” (2009). Ironically, Smith never realized how important his role in the colony had been; however, John Smith had faith that Virginia was intended for greatness (Cooper & Terrill, 2009). Another man who helped save the colony was John Rolfe, who discovered a mild form of tobacco (Cooper & Terrill, 2009). Tobacco was not native to Virginia. In fact, it had been introduced to the English by the Spanish and was grown in the West Indies (Cooper & Terrill, 2009). However, Rolfe was able to obtain some tobacco seeds and cultivated a mild form of the product (Cooper & Terrill, 2009). This crop grew in popularity back in England, which in return helped the colony by giving it economic means (Cooper & Terrill, 2009). Other colonists followed Rolfe’s lead. Tobacco even grew in the streets of Jamestown (Cooper & Terrill, 2009). The “esteemed weed,” as it was called, brought the colony wealth (Cooper & Terrill, 2009). With the help of Englishmen like Captain John Smith and John Rolfe the colony was able to survive through harsh winters, Powhatan attacks, mosquitofilled summers, labor struggles, food shortages, disease and death. Over time, the colony grew despite the hardships as more and more English settlers moved and settled in Jamestown, eventually making it the leading colony (Cooper & Terrill, 2009). 3 ARLINGTON HOUSE: FROM CUSTIS-LEE MANSION TO ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY 4 As the colony grew, English settlements dominated the lower area of the Virginia Peninsula. After the Indian Massacre of 1622, the colonists built a defensive palisade across the peninsula, including a settlement named Middle Plantation in 1632 (Greenspan, 2012). After Jamestown was burned down in the events of Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676, Virginia moved its capitol to higher ground at Middle Plantation (Greenspan, 2012). This move was meant to only be temporary while the Statehouse at Jamestown was rebuilt, but the members of the House of Burgesses discovered this temporary location was safer and more environmentally pleasant, unlike Jamestown’s swampy conditions (Greenspan, 2012). In 1699 college students at William and Mary gave a presentation to the House of Burgesses, in which it was agreed upon to officially and permanently make Middle Plantation Virginia’s capital (Greenspan, 2012). It was then renamed Williamsburg in honor of King William III of England (Greenspan, 2012). By 1717 a man named John Custis IV had moved to Williamsburg, Virginia (Arlington House, 2012). Custis was the husband of Frances Parke, the elder daughter and heiress of Daniel Parke, Governor of the Leeward Islands (Arlington House, 2012). The Custis’ were a prominent family in Virginia, both John Custis IV and John Custis III served on the Governor’s Council of Virginia (Arlington House, 2012). John Custis IV served on the council from 1727 until his death in 1749 (Arlington House, 2012). John Custis IV had only one surviving son, Daniel Parke Custis, a wealthy Virginia planter (Arlington House, 2012). In 1750, Daniel Parke Custis married Martha Dandridge (Arlington House, 2012). Together they had four children, two of ARLINGTON HOUSE: FROM CUSTIS-LEE MANSION TO ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY 5 whom died during childhood (Arlington House, 2012). A year after their last child was born, John Custis IV died, leaving Martha Dandridge Custis a wealthy widow and mother of two (Arlington House, 2012). Two years later, Martha Dandridge Custis married another Virginia planter, George Washington (Arlington House, 2012). George and Martha Washington were married on January 6, 1759 at the Custis’ White House Plantation, where they honeymooned (Arlington House, 2012). Afterward, they moved further north to Washington’s Mount Vernon Estate (Arlington House, 2012). Through their marriage, Washington became owner of her “dower share” from her marriage to Custis (Arlington House, 2012). This included becoming guardian of her two children, administrator of the Custis Estate, and owner of 85 slaves, which they took with them to Mount Vernon (Arlington House, 2012). Martha and George Washington had no children together, but raised her two children from her first marriage to Custis. Their daughter, Patsy died as a teenager during an epileptic seizure (Arlington House, 2012). Their son Jackie Custis married Eleanor Calvert, daughter of Benedict Swingate Calvert and granddaughter of Charles Calvert, 5th Baron Baltimore, in 1774 (Arlington House, 2012). Custis bought the Abingdon Estate in Fairfax County, Virginia in 1778 (Arlington House, 2012). They had seven children, but three died during infancy (Arlington House, 2012). Custis served as an aide to Washington at Yorktown in 1781 during the Revolutionary War (Arlington House, 2012). It was there at a camp he contracted “camp fever” and died making his wife a young widow (Arlington House, 2012). ARLINGTON HOUSE: FROM CUSTIS-LEE MANSION TO ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY 6 After the death of her husband Eleanor left her two youngest children, Eleanor Parke Custis and George Washington Parke Custis at Mount Vernon to be raised by the Washington’s (Arlington House, 2012). George Washington Parke Custis, the step-grandson of George Washington and only grandson of Martha Washington, was adopted by the Washington’s when he was a child and raised as a son (Arlington House, 2012). Custis became very attached to his stepfather who he was named after (Arlington House, 2012). After reaching maturity, Custis inherited large amounts of money, land and property from his natural father and grandfather (Arlington House, 2012). One of which was some land from Abingdon Estate. On this piece of land in 1802 Custis began construction on Arlington House (Arlington House, 2012). It was completed in 1818 and he intended for it to serve not only as a home, but also as a memorial to his stepfather and first President of the United States, George Washington (Arlington House, 2012). Arlington House was built on a high point on a 1,100-acre estate that had originally been purchased in 1778 by Custis’ birth father Jackie Custis (Arlington House, 2012). Custis decided to build his home here in 1802 after the deaths of George and Martha Washington (Arlington House, 2012). He originally wanted to name the estate “Mount Washington,” but was persuaded by family to name it “Arlington House” after the Custis’ family homestead on the Eastern Shore of Virginia, where his great-grandfather John Custis IV is buried near Williamsburg (Arlington House, 2012). ARLINGTON HOUSE: FROM CUSTIS-LEE MANSION TO ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY 7 Custis commissioned George Hatfield, an English architect who also worked on the design for the United States Capitol building, to design the mansion (Arlington House, 2012). The north and south wings were completed between 1802 and 1804, but the majority was not finished until thirteen years later (Arlington House, 2012). The house had two kitchens, one for summer and another for winter, but its most famous feature was most likely the grand columns on the portico, each reaching five feet in diameter (Arlington House, 2012). Custis brought with him at least sixty slaves to work at Arlington; he also had slaves at White House Plantation and Romancoke Plantation (Arlington House, 2012). All together, his slave number totaled at nearly two hundred (Arlington House, 2012). Some of these he inherited from Martha Washington’s “dower slaves” and some he bought himself (George Washington had his slaves freed in his will) (Arlington House, 2012). During this time, Custis married Mary Lee Fitzhugh in 1804 (Arlington House, 2012). The couple had four children, but only one child, Mary Anna Randolph Custis survived (Arlington House, 2012). On June 30, 1831 Custis watched Mary Anna marry Lieutenant Robert E. Lee, a recent graduate of West Point who’s father Henry Lee famously eulogized President Washington at his December 18, 1799 funeral (Arlington House, 2012). The two married at Arlington House and resided there for thirty years (Arlington House, 2012). Now Custis-Lee Mansion, the Lee’s shared this home with the Custis’ between their times traveling from multiple United States Army duty stations (Arlington House, 2012). Mrs. Lee gave birth to six out of her seven children in this house, and Lieutenant Lee, active in the United ARLINGTON HOUSE: FROM CUSTIS-LEE MANSION TO ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY 8 States Army, made it home for twenty of the possible thirty Christmases at Arlington (Arlington House, 2012). After their deaths, both George Washington Parke Custis and Mary Fitzhugh Custis were both buried on the property. On his death in 1857, George Washington Parke Custis left his estate to his daughter Mary Anna Custis Lee (Arlington House, 2012). In his will Custis left several instructions: First, Arlington House and its contents, including Custis’ collection of George Washington memorabilia, would be bequeathed to his only surviving child, Mary Anna Custis Lee, and upon her death to her eldest son, George Washington Custis Lee. Second, White House Plantation in New Kent County and Romancoke Plantation in King William County be bequeathed to this two other grandsons William Henry Fitzhugh Lee and Robert Edward Lee, Jr. Third, legacies, or cash gifts, of $10,000 each would be provided to his four granddaughters, based on the sales of other smaller properties (some properties had to wait until after the Civil War to be sold, and its doubtful that $10,000 each was ever fully paid). Fourth, property in “square No. 21, Washington City” (possibly located somewhere between present day Foggy Bottom and the Potomac River) was to be bequeathed to Robert E. Lee and his heirs. Last, Custis’ slaves, about 200, were to be freed once the legacies and debts from his debts were paid, but no later than five years after his death (fulfilled by Robert E. Lee in the winter of 1862) (Arlington House, 2012). Although Arlington House was home to Robert E. Lee for thirty years, from his wedding day until the start of the Civil War, Lee never actually owned Arlington, or any other home (Arlington House, 2012). Because the house and property of the ARLINGTON HOUSE: FROM CUSTIS-LEE MANSION TO ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY 9 Custis-Lee Mansion was left to his wife, Lee became the executor of the property (Arlington House, 2012). Robert E. Lee took his new role seriously, to the point of even taking leave from his Army post in Texas for two years to settle the affairs (Arlington House, 2012). During this time he attempted to reorganize the slaves into a more efficient labor force, hired a new overseer, cleaned the grounds, supervised the planting of crops, directed some rebuilding around the plantation and repaired the mansion’s roof (Arlington House, 2012). Slaves played an important role at the Custis-Lee Mansion. From day to day, slaves were responsible for working the fields to harvest corn and wheat, which was sold in Washington, and took care of the house (Arlington House, 2012). Although governed by the racial hierarchy of the time, some slaves had close relationship with the Custis and Lee family members. Mr. Custis seemed to rely heavily on his carriage driver, Daniel Dotson (Arlington House, 2012). Meanwhile, Mrs. Lee had a personal relationship with the head housekeeper Selina Gray (Arlington House, 2012). The closeness of their relationship is reflected in the act of Mrs. Lee handing the keys to the plantation to Selina when the Lees’ evacuated Arlington in May 1861 (Arlington House, 2012). In addition, it is suspected that some slaves at Arlington had opportunities that slaves elsewhere did not have. For example, Mrs. Custis, a devout Episcopalian, tutored slaves in basic reading and writing so that each slave could read the bible (Arlington House, 2012). Mrs. Lee and her daughters continued this practice even when Virginia law prohibited the education of slaves by the 1840s (Arlington House, 2012). Mrs. Custis also convinced her husband to free several slave women and ARLINGTON HOUSE: FROM CUSTIS-LEE MANSION TO ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY 10 children (Arlington House, 2012). Some of these emancipated slaves settled on the Arlington estate. It is documented that the Custis’ gave a seventeen-acre plot to a married slave couple at the time of their emancipation (Arlington House, 2012). Although the Custis and Lee families seemed to care for their slaves and tried to improve the quality of their lives, they still remained in legal bondage to the family (Arlington House, 2012). By February 1860, the Custis-Lee Mansion affairs were in order and Lee was able to leave for Texas to resume his army post (Arlington House, 2012). During the early stages of succession, Lee privately ridiculed the Confederacy, wishing for peaceful ways to resolve the growing tensions (Arlington House, 2012). The commanding general of the Union Army, Winfield Scott, told President Lincoln he wanted Lee for a top command and Lee accepted the position of colonel (Arlington House, 2012). In the meantime, Lee ignored an offer of command from the Confederate States of America (Arlington House, 2012). When Scott asked Lee to command the defense of Washington D.C., Lee turned down the offer, fearing it would mean invading the South (Arlington House, 2012). Evident that Virginia would succeed, a lieutenant asked Lee whether he would fight for the Union or Confederate side. It is said that he responded, “I shall never bear arms against the Union, but it may be necessary for me to carry a musket in defense of my native state Virginia…” (Arlington House, 2012). Lee asked Scott, who was also a Virginian, if he could stay home and not participate in the war, in which Scott replied, “I have no place in my army for equivocal men” (Arlington House, 2012). ARLINGTON HOUSE: FROM CUSTIS-LEE MANSION TO ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY 11 Evidence shows through Lee’s actions, quotes, and social ties that this was a difficult choice for him to make. Even amongst his family, his daughter Mary Custis seemed to be his closet family tie to favor the Confederacy, while is wife Mary Anna favored the Union (Arlington House, 2012). Therefore, it came as a surprise on April 20, 1861, when in the early morning hours in his bedroom on the second floor of Arlington House, Robert E. Lee wrote his resignation from the United States Army giving up his lifelong career for an unknown and indefinite future (Arlington House, 2012). Lee’s family followed him into the Confederacy, changing all of their lives forever. Less than a month after Lee resigned from the United States Army and took Command over all of Virginia’s forces, Mrs. Lee received word from her cousin and Union Army officer Lieutenant Orton that Union troops were headed to the CustisLee Mansion (Poole, 2009). Because Arlington was on a hill overlooking the capital, it was key for the defense of the city, otherwise Confederate troops would have a perfect platform to seize Washington D.C. (Poole, 2009). Mrs. Lee was distraught at the prospective of loosing her beloved family home, but her husband pleaded that she leave and get to safety (Poole, 2009). That night Mrs. Lee presided over 196 slaves as they boxed the family silver, packed General Lee’s possessions and stored George Washington’s belongings (Poole, 2009). She took a final walk in the garden, then entrusted the keys of the estates to her faithful slave Selina and followed her husband’s path down their long, winding driveway (Poole, 2009). Never again would the Lee Family live in their home, so filled with their history and ancestry. ARLINGTON HOUSE: FROM CUSTIS-LEE MANSION TO ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY 12 The undefended estate changed hands in an instant. On May 23, 1861, the voters of Virginia approved an ordinance to succeed from the Union (Poole, 2009). Within hours, Union forces fled the city of Washington and crossed the Potomac River on steamers, foot and horseback in swarms so thick that a Lee family slave named James Parks described them as “bees a-coming” (Poole, 2009). When the sun rose that morning the yard was flooded with men wearing Union blue (Poole, 2009). They constructed a village of army tents across the lawn, built fires for breakfast, chopped down massive oak trees to clear a line for artillery fire, and strolled across the wide portico as if it were theirs (Poole, 2009). Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper reported, “… the whole line of defenses on Arlington Heights may be said to be completed and capable of being held against any attacking force” (Poole, 2009). Although Arlington House never did see battle, the Civil War still impacted the estate evermore. Union soldiers stripped the estate’s forest of wood to build cabins and took souvenirs from the mansion for personal gain (Poole, 2009). After Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 thousands of slaves flocked to Washington in numbers so plentiful the capital could not accommodate them all (Poole, 2009). The Army took charge of the newly freed slaves and built Freedman’s Village, complete with frame houses, schools, churches, farmlands and a population of 1,500, on the grounds of Arlington House (Poole, 2009). Over the next thirty years, some of the Custis slaves, even those of descent from Mount Vernon, established permanent homes in Freedman’s Village where they were able to learn trades and attend school (Arlington House, 2012). ARLINGTON HOUSE: FROM CUSTIS-LEE MANSION TO ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY 13 In June 1862 as the war continued to heat up, Congress passed a law that empowered commissioners to assess and collect taxes on real estate in “insurrectionary districts” (Poole, 2009). The statue not only raised revenue for the war, but also punished men like Lee who left the Union (Poole, 2009). Authorities levied a tax of $92.07 on the Lees’ estate that year (Poole, 2009). Mary Custis Lee was stuck in Richmond because of the fighting and her deteriorating health with rheumatoid arthritis (Poole, 2009). Mrs. Lee sent her cousin Philip R. Fendall to pay the bill, but the commissioners of Alexandria would only accept the money from Mary Lee herself (Poole, 2009). The commissioners declared the property in default and put it up for sale (Poole, 2009). The auction took place on January 11, 1864 (Poole, 2009). The sole bid came from the federal government, offering $26,800, well under its estimated value of $34,100 (Poole, 2009). According to the bill of sale, the Custis-Lee Mansion’s new owner intended to reserve the property for “Government use, for war, military, charitable and educational purposes” (Poole, 2009). The act of appropriating the homestead was in perfect keeping with the views of President Lincoln, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, and General William T. Sherman who believed in waging total war to bring the rebellion to a conclusion (Poole, 2009). As the war dragged on, Washington D.C.’s temporary hospitals filled with sick and dying soldiers (Poole, 2009). They began to fill local cemeteries jut as General Lee and General Ulysses S. Grant began their Forty Days’ Campaign (Poole, 2009). The fighting produced around 82,000 casualties in a month’s time (Poole, 2009). ARLINGTON HOUSE: FROM CUSTIS-LEE MANSION TO ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY 14 Montgomery Meigs looked for a final resting place for these soldiers, and his eyes fell upon Arlington (Poole, 2009). The first soldier laid to rest at Arlington was Private William Christman. 21, of the 67th Pennsylvania Infantry on May 13, 1864 (Poole, 2009). A month later, Meigs moved to make the practice official writing, “I recommend that… the land surrounding the Arlington Mansion, now understood to be the property of the United States, be appropriated as a National Military Cemetery, to be properly enclosed, laid out and carefully preserved for that purpose” (Poole, 2009). Meigs proposed devoting 200 acres to the new graveyard and suggested that Christman and other recently interred soldiers in the Lower Cemetery be exhumed and reburied closer to Lee’s home, writing, “The grounds about the Mansion are admirably adapted to such as use” (Poole, 2009). Stanton approved the quartermaster’s recommendation the same day it was given, June 15, 1864 (Poole, 2009). Loyalist newspapers applauded the creation of Arlington National Cemetery (Poole, 2009). In fact, it was just one of the thirteen new cemeteries specifically created for those dying in the Civil War (Poole, 2009). Washington Morning Chronicle stated, “This and the [Freedmen’s Village]… are righteous uses of the estate of the Rebel General Lee” (Poole, 2009). Meigs insisted to oversee where the graves were being dug, stating, “It was my intention to have begun the interments nearer the mansion but opposition on the part of officers stationed at Arlington, some of whom… did not like to have the dead buried near them, caused the interments to be begun” in the Lower Cemetery (Poole, 2009). To enforce his orders, Meigs went to the extent of evicting officers ARLINGTON HOUSE: FROM CUSTIS-LEE MANSION TO ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY 15 from the mansion, installing a military chaplain and a loyal lieutenant to oversee cemetery operations, and implementing the new burials around Mrs. Lee’s garden with prominent Union officers (Poole, 2009). By the end of 1864, about forty officers were laid to rest where Mrs. Lee had formerly enjoyed reading in warm weather, surrounded by the scent of honeysuckle and jasmine (Poole, 2009). In addition, Meigs dispatched crews to scour the nearby battlefields in search of unknown soldiers (Poole, 2009). He then excavated a huge pit at the end of Mrs. Lee’s garden and filled it with the remains of over 2,000 unknown Union officers and soldiers (Poole, 2009). He purposely filled the garden with prominent officers, knowing it would make it difficult to disinter the heroes of the Union, as well as make the mansion uninhabitable for the Lee’s (Poole, 2009). At the conclusion of the war, the Lee’s wished to return home to Arlington (Poole, 2009). Mary Lee wrote to a friend the graves, “are planted up to the very door without any regard to decency … if justice and law are not utterly extinct in the U.S., I will have it back” (Poole, 2009). Her husband, however, kept his thoughts more hidden from the public and only spoke of the matter with those close to him in private stating; “I have not taken any steps in the matter under the belief that at present I could accomplish no good” (Poole, 2009). Nevertheless, he encouraged a Washington lawyer to look into the matter quietly and coordinate with his trusted legal advisor Francis L. Smith in Alexandria (Poole, 2009). General Lee’s older brother, Smith Lee, actually made a visit to the estate in 1865 (Poole, 2009). He concluded that the estate could be inhabited again if a wall was built to screen the graves from the mansion (Poole, 2009). However, he made ARLINGTON HOUSE: FROM CUSTIS-LEE MANSION TO ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY 16 the mistake of sharing his views with the cemetery superintendent, along with his identity (Poole, 2009). The superintendent dutifully shared this information with Meigs (Poole, 2009). Therefore, as the Lees’ worked to attain their home, so did Meigs work to keep them from it (Poole, 2009). The plantation home the Lees’ knew became less recognizable each year (Poole, 2009). The question of ownership was still unresolved when Lee died in 1870 at the age of 63. After General Robert E. Lee’s death, Mary Lee managed a farewell visit to Arlington in June 1873 (Poole, 2009). Escorted by a friend, Mrs. Lee rode around the grounds of the estate in a carriage for three hours taking in the scenery (Poole, 2009). She told her companion, “My visit produced one good effect, the change is so entire that I have not the yearning to go back there and shall be more content to resign all my right in it” (Poole, 2009). She died in Lexington five months later at the age of 65 (Poole, 2009). Even after the death of both his parents, the hope of Arlington lived on in George Washington Custis Lee, who would have inherited the estate under any other circumstances (Poole, 2009). Just months after his mother’s funeral, Custis Lee went to Congress with a petition and asked for an admission that the property had been taken unlawfully (Poole, 2009). Lee requested compensation for it and argued that his mother’s good-faith attempt to pay the insurrectionary tax of $92.07 was the same as if she had paid it (Poole, 2009). Even so, the petition died quietly (Poole, 2009). In March 1877, Union veteran Rutherford B. Hayes was sworn in as President on the promise of healing scars between the North and South from the Civil War ARLINGTON HOUSE: FROM CUSTIS-LEE MANSION TO ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY 17 (Poole, 2009). Custis Lee took this as an opportunity to act and revived his campaign for Arlington, this time in court (Poole, 2009). Lee, asserting ownership of the property, asked the Circuit Court of Alexandria, Virginia to evict all trespassers occupying the premises as a result of the 1864 auction (Poole, 2009). When U.S. Attorney General Charles Devens learned of the suit, he immediately asked that the case be shifted to federal court (Poole, 2009). The case went to Judge Robert W. Hughes of the U.S. Circuit Court for the Eastern District of Virginia in July 1877 (Poole, 2009). After months of legal arguments, Judge Hughes ordered a jury trial (Poole, 2009). Custis Lee’s argument centered on the legality of the 1864 tax sale (Poole, 2009). After a six-day trial, the jury found that by requiring the insurrectionary tax to be paid in person, the government had deprived Lee of his property without due process of law (Poole, 2009). On December 4, 1882, Associate Justice Samuel Freeman Miller, appointed by President Lincoln, wrote for the 5 to 4 majority for United States v. Lee, holding that the 1864 tax sale had been unconstitutional and was therefore invalid (Poole, 2009). The Lees’ had custody of Arlington once again. This posed a major problem for the federal government who was now trespassing on private property. They could abandon an Army fort on the grounds, evict the residents of Freedmen’s Village, disinter almost 200,000 graves and vacate the property, or they could buy the estate from Custis Lee, if he was willing to sell it (Poole, 2009). Thankfully for the government who had a large task ahead of them, he was. ARLINGTON HOUSE: FROM CUSTIS-LEE MANSION TO ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY 18 Both parties agreed on the price of $150,000, which was the property’s fair market value (Poole, 2009). Congress quickly appropriated the funds and Lee signed the papers turning over the title on March 31, 1883, which gave full ownership of Arlington to the United States government without any further dispute (Poole, 2009). The man who formally accepted the title of the property for the government was Robert Todd Lincoln, Secretary of War and son of former President, Abraham Lincoln (Poole, 2009). If sons of former adversaries could burry their differences, there was hope yet for the nation to reunite as one. The same year that the Supreme Court ruled in Custis Lee’s favor, Montgomery Meigs reached the age of mandatory retirement (Poole, 2009). He was a frequent visitor of Arlington, where he buried his wife, father, numerous in-laws, and his son, a fallen Union soldier (Poole, 2009). Row 1, Section 1 of Arlington National Cemetery housed more of Meigs relatives than all of Arlington did of Lee’s (Poole, 2009). Meigs joined them there in 1892. His flag-draped caisson processed passed Mary Lee’s garden, down Meigs Drive and was eased into the ground at the heart of the cemetery he created (Poole, 2009). Today, the mansion and twenty-eight acres around it, is managed by the National Park Service as a memorial to Robert E. Lee (Arlington House, 2012). The grounds, flower garden and kitchen garden still reflect the Colonial Revival style (Arlington House, 2012). The land surrounding the mansion, over half of the original 1,100 acres, known as Arlington National Cemetery is managed by the Department of the Army (Arlington House, 2012). ARLINGTON HOUSE: FROM CUSTIS-LEE MANSION TO ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY 19 Part of the original wooded grounds known as Arlington Woods still stands. Environmentalists have reported that it is one of the oldest and largest tracts of climax eastern hardwood forest in Arlington County (Arlington House, 2012). This forest is the same type that once covered the property of Arlington House, and has regenerated from trees that were present historically (Arlington House, 2012). A forestry study also reported a tree that is 258 years old, dating prior to Jackie Custis’ original purchase of Abingdon Estate in 1778 (Arlington House, 2012). Another part of the original Abingdon Plantation is now home to Ronald Reagan International Airport (Arlington House, 2012). As for Freedman’s Village, it was completely closed by 1900 for development purposes and is now home to more cemetery plots (Arlington House, 2012). Despite the challenges many of the residents faced, it was the first experience of life outside of bondage for thousands of former slaves, including a number of the former Washington-Custis-Lee family slaves, and some of their descendents still live in Arlington County today (Arlington House, 2012). The contributions of these former slaves to the Arlington Estate have not been forgotten. An article by Jesse J. Holland, recounts the experience of walking through the cemetery with Wayne Parks, a decedent of the Lee Family slaves (2010). The articles says, “Parks said he remembers his grandfather repeatedly bringing him to the cemetery as a child to explain the bond. ‘I was sitting on this wall gazing over the cemetery and all of a sudden I got it. Our DNA is intrinsically intertwined with this property” (Holland, 2010). Wayne Parks is a descendent of James Parks, a former slave and the only person buried at Arlington who was also ARLINGTON HOUSE: FROM CUSTIS-LEE MANSION TO ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY 20 born there (Arlington House, 2012). James Parks, known as “Uncle Jim” was born in 1843. He had vivid memories of George Washington Parke Custis playing fiddle near the river and could name all of the Lee children from oldest to youngest. He helped build Fort McPherson and Whipple, now Fort Myer, but stopped building forts to start digging graves. He dug many of the first cemetery plots, such as that of Private William Christman, now known as Section 27 and even prepared the grave for former quartermaster Montgomery Meigs. James Parks died in August 1929. He was laid to rest in Arlington with full military honors (Arlington House, 2012). Today Arlington National Cemetery is the most prestigious cemetery in the country, and the only cemetery to hold servicemen from every U.S. war (Klein, 2012). It acts as the final resting place for some of the nation’s most honored and decorated soldiers, former Presidents and First Ladies, Supreme Court Justices, senators, nurses, explorers and astronauts. It has become a sacred monument to our nation’s history and a symbol of respect to our armed forces. From the plantation of George Washington Parke Custis to the hollowed ground it is today, the piece of land known as Arlington National Cemetery has a unique history. This piece of land has in itself lived the American Dream. From its humble beginnings as woodlands to its connection to the very first President of the United States to each of its intermits, it sits as living proof that America may change, but she gets more esteemed and celebrated with age. ARLINGTON HOUSE: FROM CUSTIS-LEE MANSION TO ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY 21 Work Cited Arlington house, the robert e. lee memorial. (2012). National Park Services. Retrieved from http://www.nps.gov/arho/index.htm Cooper, W.J., & Terrill, T.E. (2009). The american south. (4th ed.). Lanham, MD. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. Greenspan, A. (2012). Colonial williamsburg. Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved from http://encyclopediavirginia.org/Colonial_Williamsburg Holland, J.J. (2010). Arlington graves cover ‘freedman’s village.’ NBC News. Retrieved from http://www.nbcnews.com/id/36651047/ns/us_news-life/t/arlingtongraves-cover-freedmans-village/#.UclMvGTFRU4 Klein, C. (2012). Arlington national cemetery: 8 surprising facts. History. Retrieved from http://www.history.com/news/arlington-national-cemetery-8surprising-facts Poole, R.M. (2009). How arlington national cemetery came to be. Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.smithsonianmag.com/historyarchaeology/The-Battle-of-Arlington.html?c=y&page=1