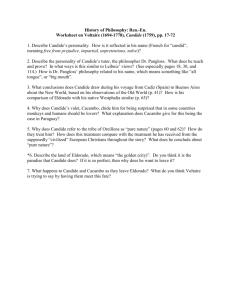

Lolita AOU English http://lolita-aou.blogspot.com Twitter https://twitter

advertisement

Lolita AOU English http://lolita-aou.blogspot.com Twitter https://twitter.com/Lolita_AOU Facebook https://www.facebook.com/lolita.aou Instagram http://instagram.com/lolita_aou Chapter 6 Voltaire, Candide, or Optimism Introduction Francois-Marie Arouet = known to literature as 'Voltaire' In this chapter, we will study: The physical and philosophical journeys of the main characters in Candide in the contexts of Voltaire's own life and intellectual world. ___________________________________________ Voltaire, his world and his book Voltaire was a writer of great comic gifts, with a vivid sense of pace. Activity 2 What are the different ways in which the idea of journeying operates throughout the text? Discussion Several kinds of travel are implicated, either directly or indirectly, in this versatile book. Among them are the personal itineraries of Candide and Cunegonde as well as the digressions from the main track taken by minor figures such as Candide's servant Cacambo. Another less literal kind of journey is the intellectual journey that follows the succession of challenges to Pangloss's ideal of 'optimism'. ___________________________________________ The routes and destinations of all of these interconnected travels constitute an absorbing mix of ideas and debate Literary and philosophical antecedents The group of wanderers in Candide seems to be driven by some sort of philosophical quest. Travel writing may seem to constitute a genre that is primarily descriptive and narrative. It tells the story - real or imagined — of a person or a group of persons voyaging from place to place. This type of writing is not neutral: 1) Travellers inevitably compare the worlds they are travelling through to their own world. 2) This can lead travellers to make negative and even racist judgements 3) It can lead them to recognise flaws in their own society; 4) It can lead them to reflect upon 'the universality of the human condition'. *** Utopian literature: utopia = good or perfect place It is appeared by the English scholar Thomas More, projected imaginary environments based upon political principles or ideals (in the case of More, religious toleration, the equal education of the sexes, and the absence of money and private property). 'Dystopian' A contrary tendency later arose whereby authors fantasised about worlds in which human ideals of a perfect society were shown to be ridiculous, or at least impracticable ___________________________________________ The genre of Candide? Candide is: 'a philosophical tale'. Another literary category often associated with Candide is that of satire, which is writing that ridicules or mocks the failings of individuals, institutions or societies. As Voltaire allows his readers to draw their own conclusions, Candide should probably be classified as 'indirect satire'. ___________________________________________ Voltaire therefore makes extensive use of literary irony: 'the use of a naive or deluded hero or unreliable narrator, whose view of the world differs widely from the true circumstances recognised by the author or readers; literary irony thus flatters its readers' intelligence at the expense of a character (or fictional narrator)'. Much of the humour in Candide is derived from the ironic distance between the narrator's words and Voltaire's satirical attack on his society. ___________________________________________ Pangloss's journey: from theory to fact Voltaire's philosophical views - expressed in literary works like Candide. Candide is overtly named after his adventurous naïve hero but it is its subtitle, 'Optimism' that announces its theme. The character of Candide's tutor Pangloss is the inexhaustible spokesman on behalf of 'Optimism', and all of the main characters in the course of their journeys test to the very limits Pangloss's creed. ((The character of Pangloss was Voltaire's exaggerated comic creation.)) **** 'Optimism' had distinct intellectual sources: 1) Pope’s Essay on Man 2) Gottfried Leibniz IMPORTANT PARAGRAPH للفهم Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz had argued the case from the nature of God. Since the creator was both omniscient (all knowing) and omnipotent (all powerful) and since he wished that his creatures should be happy, it followed of necessity that the world he had made was one that secured the most contentedness he could contrive. Leibniz did not deny that nasty things happened, or that people suffered; such a position would be ridiculous. But human beings were not omniscient (they had limited knowledge) and what appeared to them to be blemishes or setbacks could very well be part of the grand universal plan. Only God, with his serene overview, saw how. This theory is one of the most frequently cited answers to two dilemmas theologians call 'The Problem of Evil' and 'The Problem of Pain'. Both pain and evil seem contradictory in a world supposedly overseen by a compassionate governor. In Candide, Voltaire repeatedly points this out. The truth is that they were tackling the same issue from opposite ends of a spectrum. Leibniz approach might be characterised as arguing forward from certain assumptions: since God is perfect by definition, it follows that he can do no wrong. Voltaire's approach might be described as empirical: he used his experience of the world around him to draw certain conclusions about it. ___________________________________________ IMPORTANT ACTIVITY Activity 4 Contrast Voltaire's views on 'optimism' with those of Pope (and Leibniz): Discussion Chapter 5 of Candide attacks the cosmic complacency, the thin optimism, expressed in Pope's Essay on Man. The weapon used is ridicule, a technique at which Voltaire is particularly adept. Leibniz's ideas are expressed by Candide's tutor Pangloss, and are repeatedly shown up as preposterous. As example of how Voltaire exposes the limitations of Pangloss's philosophy of optimism (and by extension Pope's and Leibniz's) is during the dinner after the earthquake, when he declares: 'This is all for the best ... For if there is a volcano beneath Lisbon, then it cannot be anywhere else; for it is impossible for things to be elsewhere than where they are. For all is well' (p. 14). In the context of the devastation caused by the earthquake, Pangloss's parroting of Pope's and Leibniz's creed of optimism comes across as especially platitudinous and inadequate. ___________________________________________ Voltaire's attack on the ideas of Leibniz and Pope is not limited to matters of content: his very style of writing is an assault upon what he saw as their self-deluding optimism. The title of Candide is principally taken from the name of its protagonist, but it applies equally well to its style. This is a book that pulls no punches, makes no effort to be civil, even rejoices in its earthy rudeness. It says it how it is. Voltaire's candour is therefore integral to his message. His target is the sort of moral dishonesty, present in most ages, that flinches away from the facts and pretties them up with mealymouthed, sociably acceptable persiflage. ___________________________________________ Cunegonde's journey: candour not cant The unworldly Doctor Ralph is not the only narrator in Candide. There are three episodes in the novel recounted by women: - Chapter 8 is narrated by Candide's beloved, Cunegonde, who retells the events of the opening chapters from her perspective; Chapters 11 and 12 are narrated by the old woman, who tells Cunegonde the story of her calamitous life; and the first part of Chapter 24 is narrated by Pacquette, who disabuses Candide of his perception that she is happy by describing her decline from serving maid to prostitute. In these episodes, told from a feminine perspective, Voltaire gives us history from the point of view of its victims. We register that Voltaire is satirising the creed of Pope and Leibniz, in these three episodes, narrated by female characters, Pangloss's sanguine apathy is exposed as an overwhelmingly masculine delusion by the blunt facts of female subservience in a male-dominated society. All three women tell tales of spectacular suffering and misadventure, which are nonetheless lightened by their transparent absurdities and extravagant hyperbole. The most important of the female characters in Candide is Cunegonde: In terms of the plot: much of Candide's journeying is in search of Cunegonde. Aside from its comic effects, her name also discloses Voltaire's concern in Candide to promote the quality of candour. Voltaire's reliance on associations conjured up by her name is in keeping with her own frankness about the body. Several other implications seem to be present: that what we commonly regard as beautiful may also be quite obscene, or that what we commonly regard as obscene may in fact be quite beautiful. During the course of her tribulations, Cunegonde has sometimes been reduced to a sexual plaything. ___________________________________________ Activity 5 Reread Chapter 8, 'Cunegonde's Story', and think about the style, tone and the way in which the tumultuous events are narrated. How much difference does it make that the narrator of this story is a woman? Discussion Chapter 8 constitutes a flashback (it retells the events of Chapters 2 to 7 from Cunegonde perspective). As such, it inserts into the tale a feminine point of view at variance with, or at least complementary to, Doctor Ralph's main narrative. Cunegonde is recounting her story in Lisbon, which gives Voltaire a chance to portray the injustices meted out in this traditionalist Catholic society on four minorities: women, Protestants, intellectuals and Jews. Like the rest of the book, however, her narrative involves journeys, beginning in Westphalia where the assault on the Baron's castle is retold from the point of view of one of its female victims. After she is rescued from being raped by the Bulgar soldier, for example, she concedes that she is physically attracted to her rescuer. Cunegonde recounts all of this with supreme honesty, and in this she expresses herself very much in the same spirit as Voltaire himself. Cunegonde's candour is also directed at Voltaire's philosophical targets, and in direct contrast to Doctor Ralph, Cunegonde concludes from her awful experiences that Pangloss is utterly wrong: 'Pangloss deceived me cruelly, after all, when he told me that all is for the best in this world' (p. 21). ___________________________________________ Voltaire is indicating an older idea: the ladder of the great chain of being which, in the Renaissance period, was thought to support all human hierarchies. The ladder reached down from God to the lowliest pebble, but women and Jews were both allotted very low rungs at the human level. ___________________________________________ Activity 6 Discussion 1 in this passage, Voltaire is only concerned to exploit the comic potential of the scene, and to enjoy the ridiculousness of the poor man's predicament. Frankness and farce could not go much farther. Voltaire's prevailing tone here is comic, even at times consciously farcical. 2 Voltaire's tone in the second passage is rather different. The slave recounts his sufferings, from his mother selling him on the coast of Guinea, to his Dutch master in Surinam cutting off his right hand and left leg. The slave's African mother and his Dutch owner both benefit by his enslavement, but the slave declares himself to be a thousand times more miserable than dogs, monkeys and parrots. Voltaire's tone here is far from comic; instead his satire assumes a serious edge in order to express unequivocally how much he abominates slavery. ___________________________________________ In order for such a counterblast to the apathy of optimism to work, it must be narrated candidly, with no avoidance of unpleasant facts. The female narrators, as well as the Dutch slave in Surinam, are not in the slightest bit delicate when it comes to telling people about the cruelties, perversities and humiliations that have been their lot. They tell their histories throughout with unflinching honesty and candour. ___________________________________________ Cacambo's journey: the best of impossible worlds Activity 7 = important Reread Chapter 18, 'What they saw in the land of Eldorado', paying particular attention to the interview with the 172-yearold citizen of El Dorado, the reception at court, and Candide and Cacambo's decision to leave the country and return to Europe. Two related contradictions seem to be present throughout this passage. Discussion (1) The chapter amounts to a critique of value in which the ethical and material standards of the visitors are played off against those of their hosts. Voltaire works this trick from the very beginning, contrasting the perceptions of the boggleeyed tourists to those of the contented, if slightly blase, natives. The old man lives in a 'modest house', the door of which is 'merely of silver and the panelling in the apartment merely of gold' (p. 46). This sounds like irony, but it is only so in the eyes of the reader and of Candide and Cacambo. To the old man, the house really is modest, the effect of its decor, to which he is quite habituated, one of 'bare simplicity' (p. 46). Those who live in this earthly Paradise are quite unaware of this fact, though they are also conscious of the unseemly and irrational effects that rumours of their land have had on the minds of outsiders. They regard these dreams with muted contempt, because in their country what is priceless to others is so common as to be without value to the inhabitants. The effect from the reader's point of view is to bring into question the whole subject of value. (2) With regard to the second apparent contradiction, Candide and Cacambo are subliminally aware of the unreality of the place they have stumbled upon and are soon anxious to leave it. They head for the smoke and the stress. But there is another, far more cynical, reason for their departure. The untold wealth around them is as valueless to them as it is to the indigenous people, as long as it remains where it is. If, like the Spanish before them, they can arrange to take it away, the situation would be very different. Then the value system beyond El Dorado will swing back into operation: Candide declares that if they leave El Dorado, 'we shall be richer than all the kings put together, we shall no longer have Inquisitors to fear, and we shall easily rescue Cunegonde' (p. 49). According to the narrator, Cacambo was persuaded by Candide's argument, and so they arranged to have some sheep loaded up with gold, and are winched across the mountains to the world beyond. ___________________________________________ Where does this leave the expectations of those raised on the philosophy of Leibniz, or his disciple Pangloss? The answer is that it again subjects such teaching to a thoroughgoing critique, with surprising results. The implication of Candide's and Cacambo's experience of El Dorado is that there are plenty of worlds that are better; they are just unrealisable. This then is Utopia; simultaneously a perfect and a nonexistent place. ___________________________________________ Candide's journey: governed by fate or free will It is significant that Candide and his band of travellers conclude their journeys in Turkey, a region still dominated by the declining Ottoman Empire, widely and not entirely inaccurately supposed to be despotic. One of the most deeply rooted perceptions present in the eighteenth-century European mind was that a stubborn belief in, and quiescence before, fate or destiny was a characteristic of the peoples of the 'Orient'. In the minds of Voltaire and his contemporaries, such despotic regimes in such places were aided and abetted by the inherent fatalism of the East. The Turkish people, according to this interpretation, were oppressed largely because they believed in fate, and thus held their subjection to be inevitable. The Palestinian critic Edward Said argues that during the centuries when the cultures of the West had predatory designs on the lands of the East, a belief in oriental passivity and fatalism served as a useful adjunct to these plans of acquisition. Peoples who were temperamentally pessimistic were easily dominated, by their own rulers or by outsiders. In the West, it was supposed, men and women were more likely to believe in freedom of choice and were therefore more inclined to resist tyranny. ___________________________________________ Activity 9 Reread Chapter 30, 'Conclusion', paying particular attention to: the characterisation of the Dervish and his philosophy the characterisation of the old man and his philosophy the ultimate fate of Pangloss and his arguments. What do these final pages tell us about Voltaire's own ideas about free will and fate? Discussion Voltaire's attitude here seems to be one of thoroughgoing relativism. The Dervish-philosopher is 'great', but mainly in the eyes of his disciples. He is quite detached from the world and advises Candide and his band to withdraw from the world too: in reply to Pangloss's question 'So what must we do?', he says, 'Keep your mouth shut' (p. 92). The interview concludes with the Dervish-philosopher slamming the door in Pangloss's face, when the latter proposes to discuss the relative merits of freedom and destiny. The old man on the farm also expresses a detached attitude towards the machinations of powerful people in the big city: 'I never enquire about what goes on in Constantinople' (p. 92), he declares. But if both these machinations and his indifference to them are predestined, who are Candide and Pangloss to object? As a matter of fact, they do not object, but retire to their own garden and do likewise. Pangloss predictably considers everything that has happened to be confirmation of his creed, even though the disappointments he and his companions have endured contradict it. Pangloss's last statement is a triumphant reassertion of his belief system to which he has remained true through all manner of vicissitudes and adversity. But notice that Candide makes no attempt to contradict him; instead, he remarks That is well said', before going on to express his own hard-won pragmatic nostrum, 'but we must cultivate our garden' (p. 94). In the last chapter of Candide, Voltaire is therefore trying to see the idea of destiny from several points of view. These include not only different schools of philosophy, but also the perspectives on this common problem adopted by different cultures, Eastern and Western. Hence travel writing and the philosophical tale come together - the argument travels with the story. Have they then succumbed to Eastern fatalism? Have Candide and his companions found minimal fulfilment at last, or have they simply stopped trying, something that Voltaire himself never did? These are paradoxes that Voltaire quite deliberately refrains from solving for us. As Voltaire very well knows, you cannot have it both ways; you cannot believe in freedom and fate at the same time. Or can you? ___________________________________________ In the face of all of these bewildering contradictions, Candide's recommendadon that he and his friends cultivate their own private patch or garden may seem like a shrug in the face of the difficulties, as well as a gesture of complicity with the attitudes of the old man on the farm. But it is a lot more and other than this. We should not ignore the possibility that, at a practical, salutary level, Voltaire was commending gardening as a therapeutic solace. Gardens are pleasant places, and Voltaire was fond of his own. For Voltaire, the candid response, it seems, is to work or sit in your garden, with a book or without one. ما شاء هللا ال قوة إال باهلل مع تمنياتي لكم بالتوفيق أختكم لوليتا المبيكا هذا العمل خالص لوجه هللا وصدقة جارية على روحي في الحياة والممات فال تنسوني من دعائكمو تمت مساعدتي بالحصول على المادة العلمية لعدم توفر الكتب عندي باغي االجر اخوكم (برنارد شو) حبا في فعل الخير راجيا منكم الدعاء ال أحلل استخدام هذا الملف بأي شكل من األشكال في إعادة النشر أو عمل ملخصات