Memory - Department of Psychology

advertisement

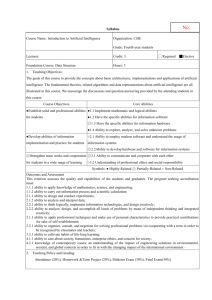

Memory (Continued) and Intelligence Lecture 5 October 10, 07 Outline for Today’s Class • How does memory function in everyday situations? • How do older adults perceive their memory? • What can older adults do to help their memory? • What is intelligence? • What are the factors moderating changes in cognitive abilities? Is Memory Always Accurate? • Older adults seem more vulnerable to generate false memories. e.g.: The false fame experiment. • Older adults are less apt to remember the source of information they have learned, making them more vulnerable to effects of familiarity. • However, one caveat to that finding is presented in the Rahhal et al. (2002) paper. Are There Sources Older Adults Can Remember? • Perceptual (voice) vs. Conceptual (truth, value statement about the person in photograph) information • Young adults were more reliable when it came to voice source, but there was no age difference for truth/value statement. • Older adults are better at remembering affective, value-based details than perceptual ones. More About Source Memory • May & Rahhal (2005) found further evidence that only emotional conceptual information supports recall (e.g. remembering if food is rotten or not at a wedding reception), while percepetual and nonemotional conceptual do not (e.g.: remembering the location of food items or temperature at which food should be served.) • Same for remember car information: colour (perceptual) vs. class (non-emotional conceptual) vs. safety (emotional conceptual). Can The Presentation of a Memory Task Influence Performance? • In older adults, instructions make a big difference. • Rahhal et al. (2001): Instructions which emphasized the memory nature of a task led to a poorer performance than when it did not… Why? • Generating better strategies? Memory for Text • Text clearly organized: Fewer age-related differences. Why? • Rapid presentation, highly unpredictable or unorganized material, and densely presented material have adverse effects. • Differences disappear when speed of presentation is controlled. • Personal beliefs or knowledge influence recall. Example- Logical Memory Subtest of WMS Memory for Situation Models • Younger and older adults are similar in ability to construct and update situation models – Exception: older adults take longer to memorize maps and have slower reading times • Older adults use integrative or interpretive style for non-fables, whereas younger adults use more literal or text-based style • No age differences are found for fables • Benefits of prior knowledge is similar for older and younger adults • Social context matters in the way stories are retold—for older adults, it depends on the listener. Video • The Secret Life of the Brain- The Aging Brain: Through Many Lives Call number: 6425 • Why is forced use of a weakened limb so important? What are the mechanisms underlying this technique? • What are the neurological changes that may affect memory as people age? • How can physical activity contribute to better cognition? • How is Alzheimer’s disease diagnosed? • What are some of the difficulties exhibited by the patient diagnosed with AD in the video? • What are the pathological changes underlying AD? Text Memory and Episodic Memory • Both are affected by a similar set of variables. • Being old does not necessarily mean that one cannot remember, especially if the situation provides an optimal opportunity to do so, such as helpful cues to organize the information are provided. Age-related deficits in route learning • Wilkniss and colleagues (1997) pinpointed 4 deficits in route-learning seen in older adults: 1) Tend to focus only on specific, salient features (Lipman, 1991) 2) Difficulty in selecting optimal environmental features to help navigation (Kirasic et al., 1992) 3) Difficulty in organizing features temporally and spatially (Lipman, 1991) 4) Deficit in acquisition and use of diagrams (Lipman & Caplan, 1992) • Older adults experience more difficulties with abstraction. They are less efficient at transferring knowledge acquired in 2D to 3D environments. Age-related deficits (continued) • Kirasic (1991) conducted a study in a real-life supermarket showing that older adults tend to be slower than young adults at acquiring spatial info in a novel environment. • Older participants performed better in a familiar supermarket, but still did more poorly than young participants. Model of way-finding behaviour • Kirasic (2000): Model of way-finding behaviour. Age is negatively correlated with general spatial ability as established by neuropsychological tests. • This general spatial factor influences learning of environmental layout but a significant portion of the relationship between environmental knowledge and age remains unaccounted for by general spatial ability. Time To Completion For Each Trial 200 180 160 Time (s) 140 120 100 80 60 40 Young adults 20 Older adults 0 Trial 1 Trial 2 Trial 3 Trial 4 Trials Trial Path B Trial Short Delay Trial Long Delay Number of Wrong Turns Number of Wrong Turns For Each Trial 1,2 Young adults 1 Older adults 0,8 0,6 0,4 0,2 0 Trial 1 Trial 2 Trial 3 Trial 4 Trials Trial Path B Trial Short Delay Trial Long Delay Examples of recognition slides Building present in the city Sample slide of a foil Recognition Task 30 Young adults Older adults 25 Score 20 15 10 5 0 Total Recognition Score False Positives False Negatives Prospective Memory • Remembering to perform a planned action in the future – Remembering to take one’s medication – Correlated with busy lifestyle as well as age • Differences in time-related and event-related prospective memory task – Time-based task more difficult for older adults – Availability of cues are important Memory for Pictures • Although older adults are clearly worse in remembering words, researchers did not find significant age differences in memory for pictures. • Older adults rely more on schema to “fill in the blanks”. Self-Evaluations of Memory Abilities • Researchers focus on two types of awareness about memory 1. Knowledge of how memory works 2. Self evaluation – memory monitoring Age Differences in Metamemory • Differences in age is explored mainly by use of questionnaires • Belief in inevitable decline is potentially damaging The Role of Memory Self-Efficacy • Perception of one’s own memory can influence its functioning. • Memory self-efficacy is a key aspect of metamemory & to understanding other aspects of aging, such as mastering the environment • Overall, older adults with lower memory selfefficacy perform worse on memory tasks Age Differences in Memory Monitoring • Predictions without experience – Estimating performance • Predictions after experience – Regardless of age, adults overestimate performance on recall tasks, but underestimate performance on recognition tasks • Comparing prediction types – Age difference depends on tasks Abnormal Changes in Memory • Mild Cognitive Impairment vs. Alzheimer’s disease: What is the difference? – Starting drugs earlier to hope to preserve function: Aricept & Donepezil • Nun Study • Depression: Mimicking some of the changes seen in Alzheimer’s disease • However depression impacts attentional processes further than AD does. Training Memory Skills • Memory strategies – Paying attention to incoming information – Making connections with stored information • The E-I-E-I-O framework strategy – Explicit memory – Implicit memory – External memory aids – Internal memory aids – The aha or O! Memory and Aging Program • Developed by Angela Troyer in 1997 at Baycrest • Various components: – Education about memory – Relaxation training – External strategies (AWORM) • Benefits (from program evaluation) – Increased knowledge – Increased confidence/self-efficacy – Increased number of strategies • Memory Intervention Program Memory tools: Attention Writing Organization Repetition Meaningfulness Courtesy of Dr. Angela Troyer, Psychology Department, Baycrest Organization AWORM • Organize information to be remembered. Courtesy of Dr. Angela Troyer, Psychology Department, Baycrest ginger ale turnip chicken carrots steak milk salmon beans orange juice broccoli hamburger wine Repetition AWORM • At first, repeat the information over short intervals. • Eventually, repeat the information over long intervals. Spaced Repetition Courtesy of Dr. Angela Troyer, Psychology Department, Baycrest Immediately 5 seconds later 10 seconds later 30 seconds later 1 minute later 2 minutes later 5 minutes later 15 minutes later 30 minutes later Courtesy of Dr. Angela Troyer, Psychology Department, Baycrest Meaningfulness • Think of what something means. • Visualize a picture. • Associate it with something else. Courtesy of Dr. Angela Troyer, Psychology Department, Baycrest AWORM Strategies to Benefit Memory • External memory aids – Computer or PDA – Date books or post-it notes • Internal memory aids – Mental imagery – Method of loci – Mental retracing – Acronyms Other Strategies to Improve Memory • Exercising Memory – Practice organizing a grocery list – Physical and mental activity may serve as a protective factor later in life • Memory Drugs – Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors – Modest short term improvement only • Combining Strategies – Tailor the intervention to fit the problem Defining Intelligence • Intelligence involves more than just a particular fixed set of characteristics • Laypersons and experts agree on three clusters of intelligence – Problem-solving ability – Verbal ability – Social competence The Big Picture: A Life-Span View • Theories of intelligence have four concepts – Multidimensional – Multidirectionality – Plasticity – Interindividual variability • The dual component model of intellectual functioning – Mechanics of intelligence – Pragmatics of intelligence Research Approaches to Intelligence • The psychometric approach – Measuring intelligence as a score on a standardized test • Focus is on getting correct answers • Example: Wechlser Adult Intelligence Scale • The cognitive-structural approach – Ways in which people conceptualize and solve problems emphasizing developmental changes in modes and styles of thinking Measuring Intelligence • Primary Mental Abilities (Thurstone, 1938; Ekstrom et al.,1979; Schaie, 1994, 1996) – Numerical facility – Word fluency – Verbal meaning – Inductive reasoning – Spatial orientation – Perceptual speed – Verbal memory Age-Related Changes in Primary Abilities • Data from K. Warner Schaie’s Seattle Longitudinal Study of more than 5000 individuals from 1956 to 1998 in six testing cycles – People tend to improve on primary abilities until late 30s early 40s – Scores stabilize until mid-50s early 60s – By late 60s consistent declines are seen – Nearly everyone shows a decline in one ability, but few show decline on four or five abilities Secondary Mental Abilities • At least six secondary mental abilities have been found (Table 8.1) – Fluid Intelligence (Gf) • Abilities that make you a flexible and adaptive thinker, to draw inferences, and relationships between concepts independent of knowledge and experience – Crystallized Intelligence (Gc) • The knowledge acquired through life experience and education in a particular culture Moderators of Intellectual Change • Cohort differences – Comparing longitudinal studies with crosssectional show little or no decline in intellectual performance with age • Information processing – Perceptual speed may account for age-related decline – Working memory decline may account for poor performance of older adults if coordination between old and new information is required Moderators of Intellectual Change • Social and lifestyle variables – Differences in cognitive skills needed in different occupations makes a difference in intellectual development – Higher education and socioeconomic status also related to slower rates of intellectual decline – Does a cognitively engaging lifestyle predict greater intellectual functioning? • Personality – High levels of fluid abilities and a high sense of internal control lead to positive changes in people’s perception of their abilities Moderators of Intellectual Change • Health – A connection between disease and intelligence has been established in general and in cardiovascular disease in particular – The participants in the Seattle Longitudinal Study who declined in inductive reasoning had significantly more illness diagnoses and visits to physicians for cardiovascular disease – Hypertension is not as clear. Severe HT may indicate decline whereas mild HT may have positive effects on intellectual functioning Moderators of Intellectual Change • Relevancy and appropriateness of tasks – Traditional tests have high correlation with tests that have been updated to measure actual tasks faced by older persons • Modifying primary abilities – Training seems to slow declines in some primary abilities • Project ADEPT and Project ACTIVE – Ability-specific training does improve in primary abilities – Effects varies in ability to maintain and transfer gains Moderators of Intellectual Change • Other attempts to train fluid abilities – Schaie and Willis’ cognitive training • Long-term effects of training – Seven year follow-up to the original ADEPT showed significant training effects – 64% of trained group’s performance was above the pre-training level compared to 33% of the control group