Renaissance Period

advertisement

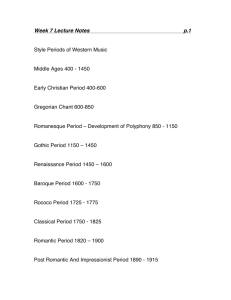

Stylistic Periods Western Music can be divided into the following stylistic periods: MIDDLE AGES 450 1450 RENAISSANCE 1450 1600 BAROQUE 1600 1750 CLASSICAL 1750 1820 ROMANTIC 1820 1900 20TH CENTURY 1900 1945 20TH CENTURY 1945 PRESENT 1 The Middle Ages (450-1450) 2 The Middle Ages (450-1450) The Middle Ages are commonly dated from the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century to the beginning of the Renaissance in the 15th century. 3 The Middle Ages (450-1450) • The only medieval music which can be studied is that which was written down, and survived. • Creating musical manuscripts was very expensive, due to the expense of parchment, and the huge amount of time necessary for a scribe to copy it all down, only wealthy institutions were able to create manuscripts which have survived to the present time. • These institutions generally included the church and church institutions, such as monasteries; some secular music, as well as sacred music, was also preserved by these institutions. 4 The Middle Ages (450-1450) • These surviving manuscripts do not reflect much of the popular music of the time. • At the start of the era, the notated music is presumed to be monophonic and homo rhythmic with what appears to be a unison sung text and no notated instrumental support. • Earlier medieval notation had no way to specify rhythm, although neumatic notations gave clear phrasing ideas, and somewhat later notations indicated rhythmic modes. 5 The Middle Ages (450-1450) • The simplicity of chant, with unison voice and natural declamation, is most common. • The notation of polyphony develops, and the assumption is that formalized polyphonic practices first arose in this period. • Harmony, in consonant intervals of perfect fifths, unisons, octaves, (and later, perfect fourths) begins to be notated. Rhythmic notation allows for complex interactions between multiple vocal lines in a repeatable fashion. • The use of multiple texts and the notation of instrumental accompaniment developed by the end of the era. 6 The Middle Ages (450-1450) The instruments used to perform medieval music still exist, though in different forms. The medieval cornett differed immensely from its modern counterpart, the trumpet, not least in traditionally being made of ivory or wood rather than metal. Cornetts in medieval times were quite short. They were either straight or somewhat curved, and construction became standardized on a curved version by approximately the middle 15th century. In one side, there would be several holes. 7 The Middle Ages (450-1450) The flute was once made of wood rather than silver or other metal, and could be made as a side-blown or end-blown instrument. The recorder, on the other hand, has more or less retained its past form. The gemshorn is similar to the recorder in having finger holes on its front, though it is really a member of the ocarina family. One of the flute's predecessors, the pan flute, was popular in medieval times, and is possibly of Hellenic origin. This instrument's pipes were made of wood, and were graduated in length to produce different pitches. 8 The Middle Ages (450-1450) Many medieval plucked string instruments were similar to the modern guitar, such as the lute, mandora and gittern. The dulcimers, similar in structure to the psaltery and zither, were originally plucked, but became struck in the 14th century, when new technology made metal strings possible. The hurdy-gurdy was (and still is) a mechanical violin using a rosined wooden wheel attached to a crank to "bow" its strings. Instruments without sound boxes such as the Jew's harp were also popular. Early versions of the organ, fiddle (or vielle), and trombone(called the sackbut) existed as well. 9 The Middle Ages (450-1450) Genres In this era, music was both sacred and secular, although almost no early secular music has survived, and since notation was a relatively late development, reconstruction of this music, especially before the 12th century, is currently subject to conjecture. 10 The Middle Ages (450-1450) Theory and notation In music theory, the period saw several advances over previous practice, mostly in the conception and notation of rhythm. Previously, music was organized rhythmically into "longs" and "breves" (in other words, “longs & shorts"), though often without any clear regular differentiation between which should be used. The most famous music theorist of the first half of the 13th century, Johannes de Garlandia, was the author of the De mensurabili musica (about 1240), the treatise which defined and most completely elucidated the rhythmic modes, a notational system for rhythm in which one of six possible patterns was denoted by a particular succession of note-shapes (organized in what is called "ligatures"). 11 The Middle Ages (450-1450) Theory and notation The melodic line, once it had its mode, would generally remain in it, although rhythmic adjustments could be indicated by changes in the expected pattern of ligatures, even to the extent of changing to another rhythmic mode. A German theorist of a slightly later period, Franco of Cologne, was the first to describe a system of notation in which differently shaped notes have entirely different rhythmic values (in the Ars Cantus Mensurabilis of approximately 1260), an innovation which had a massive impact on the subsequent history of European music 12 The Middle Ages (450-1450) Theory and notation Phillip de Vitry is most famous in music history for writing the Ars Nova (1322), a treatise on music which gave its name to the music of the entire era. His contributions to notation, in particular notation of rhythm, were particularly important, and made possible the free and quite complex music of the next hundred years. In some ways the modern system of rhythmic notation began with Vitry, who broke free from the older idea of the rhythmic modes, short rhythmic patterns that were repeated without being individually differentiated. The notational predecessors of modern time meters also originate in the Ars Nova. 13 The Middle Ages (450-1450) Early chant traditions Chant (or plainsong) is a monophonic sacred form which represents the earliest known music of the Christian church. The Jewish Synagogue tradition of singing psalms was a strong influence on Christian chanting. Chant developed separately in several European centers. The most important were Rome, Spain, Gaul, Milan, and Ireland. These chants were all developed to support the regional liturgies used when celebrating the Mass there. Each area developed its own chants and rules for celebration. In Spain, Mozarabic chant was used and shows the influence of North African music. The Mozarabic liturgy even survived through Muslim rule, though this was an isolated strand and this music was later suppressed in an attempt to enforce conformity on the entire liturgy. In Milan, Ambrosian chant, named after St. Ambrose, was the standard, while Beneventan chant developed around Benevento, another Italian liturgical center. Gallican chant was used in Gaul, and Celtic chant in Ireland and Great Britain. 14 The Middle Ages (450-1450) Early chant traditions Around 1011 AD, the Roman Catholic Church wanted to standardize the Mass and chant. At this time, Rome was the religious centre of western Europe, and Paris was the political centre. The standardization effort consisted mainly of combining these two (Roman and Gallican) regional liturgies. This body of chant became known as Gregorian Chant. By the 12th and 13th centuries, Gregorian chant had superseded all the other Western chant traditions, with the exception of the Ambrosian chant in Milan, and the Mozarabic chant in a few specially designated Spanish chapels. 15 The Middle Ages (450-1450) Gregorian chant is the central tradition of Western plainchant, a form of monophonic, unaccompanied sacred song of the western Christian Church. Although it had pretty much fallen into disuse after the 1600s, it experienced a revival in the 19th Century in the Roman Catholic Church and the Anglo-Catholic wing of the Anglican Communion. Gregorian chant was organized, codified, and notated mainly in the Frankish lands of western and central Europe during the 9th and 10th centuries, with later additions and redactions, but the texts and many of the melodies have antecedents going back several centuries earlier. Although popular legend credits Pope Gregory the Great with inventing Gregorian chant, scholars believe that the chant bearing his name arose from a later Carolingian synthesis of Roman and Gallican chant. 16 The Middle Ages (450-1450) Gregorian chant Gregorian chants are organized into eight scalar modes. Typical melodic features include characteristic incipits and cadences, the use of reciting tones around which the other notes of the melody revolve, and a vocabulary of musical motifs woven together through a process called centonization to create families of related chants. 17 The Middle Ages – Gregorian Chant Although the modern major and minor scales are strongly related to two of the church modes, the modern eight-tone scale is based on different harmonic principles and is organized differently from the scales of the church modes, which are based on six-note patterns called hexachords. The main notes in a hexachord are the dominant and the final. Depending on where the final falls in the sequence of the hexachord, the mode is characterized as either authentic or plagal. Modes with the same final share certain characteristics, and it is easy to modulate back and forth between them, hence the eight modes fall into four larger groupings based on their finals. 18 The Middle Ages Gregorian chant had a significant impact on the development of medieval and Renaissance music. Modern staff notation developed directly from Gregorian neumes. The square notation that had been devised for plainchant was borrowed and adapted for other kinds of music. Certain groupings of neumes were used to indicate repeating rhythms called rhythmic modes. Rounded noteheads increasingly replaced the older squares and lozenges in the 15th and 16th centuries, although chant books conservatively maintained the square notation. By the 16th century, the fifth line added to the musical staff had become standard. The bass clef and the flat, natural, and sharp accidentals derived directly from Gregorian notation. 23 The Middle Ages - Organum Early polyphony: organum Around the end of the ninth century, singers in monasteries such as St. Gall in Switzerland began experimenting with adding another part to the chant, generally a voice in parallel motion, singing in mostly perfect fourths or fifths with the original tune. This development is called organum, and represents the beginnings of harmony and, ultimately, counterpoint. Over the next several centuries organum developed in several ways. The most significant was the creation of "florid organum" around 1100, sometimes known as the school of St. Martial (named after a monastery in south-central France, which contains the best-preserved manuscript of this repertory). In "florid organum" the original tune would be sung in long notes while an accompanying voice would sing many notes to each one of the original, often in a highly elaborate fashion, all the while emphasizing the perfect consonances (fourths, fifths and octaves) as in the earlier organa. 24 The Middle Ages - Organum Early polyphony: organum Later developments of organum occurred in England, where the interval of the third was particularly favored, and where organa were likely improvised against an existing chant melody, and at Notre Dame in Paris, which was to be the centre of musical creative activity throughout the thirteenth century. Much of the music from the early medieval period is anonymous. Some of the names may have been poets and lyric writers, and the tunes for which they wrote words may have been composed by others. Attribution of monophonic music of the medieval period is not always reliable. Surviving manuscripts from this period include the Musica Enchiriadis, Codex Calixtinus of Santiago de Compostela, and the Winchester Troper. 26 The Middle Ages – Ars antiqua The flowering of the Notre Dame school of polyphony from around 1150 to 1250 corresponded to the equally impressive achievements in Gothic architecture: indeed the centre of activity was at the cathedral of Notre Dame itself. Sometimes the music of this period is called the Parisian school, or Parisian organum, and represents the beginning of what is conventionally known as Ars antiqua. This was the period in which rhythmic notation first appeared in western music, mainly a context-based method of rhythmic notation known as the rhythmic modes. 28 The Middle Ages – Notre Dame Polyphony Music example: (from School of Notre Dame) Perotin: Alleluia: Nativitas (The Birth) Perotin was the first known composer to write for more than two voices. An Organum in three voices is based on a Gregorian alleluia melody- for the nativity of the Virgin Mary – that Perotin placed in the lowest part. In this recording the three voice parts are sung by male voices accompanied by instruments A chant that is used as the basis for polyphony is known as a cantus firmus (fixed melody) 29 The Middle Ages – Notre Dame Polyphony Music example: (from School of Notre Dame) Perotin: Alleluia: Nativitas (The Birth) Above the cantus firmus, or preexisting melody, Perotin wrote two additional lines that move much more quickly. As many as sixty-six tones of the upper voices are sung against one long tone of the chant Only three tones are treated in this dronelike way, the first, the second and the last. The relentless rhythmic patterns of long-short-long in the top juxtaposed against the rhythm of the bottom voices is typical of medieval polyphony The narrow range of the three voices is also typical and are never more than an octave apart. 30 The Middle Ages – Ars antiqua This was also the period in which concepts of formal structure developed which were attentive to proportion, texture, and architectural effect. Composers of the period alternated florid and descant organum (more note-against-note, as opposed to the succession of many-note melismas against long-held notes found in the florid type), and created several new musical forms: Clausulae - which were melismatic sections of organa extracted and fitted with new words and further musical elaboration Conductus - which was a song for one or more voices to be sung rhythmically, most likely in a procession of some sort Tropes - which were rearrangements of older chants with new words and sometimes new music. 31 The Middle Ages Time line of significant composers of the Middle ages 33 The Middle Ages France: Ars nova During the Ars nova era, secular music acquired a polyphonic sophistication formerly found only in sacred music, a development not surprising considering the secular character of the early Renaissance (and it should be noted that while this music is typically considered to be "medieval", the social forces that produced it were responsible for the beginning of the literary and artistic Renaissance in Italy—the distinction between Middle Ages and Renaissance is a blurry one, especially considering arts as different as music and painting). 42 The Middle Ages – Ars Nova France: Ars nova The term "Ars nova" (new art, or new technique) was coined by Philippe de Vitry in his treatise of that name (probably written in 1322), in order to distinguish the practice from the music of the immediately preceding age. The dominant secular genre of the Ars Nova was the chanson, as it would continue to be in France for another two centuries. These chansons were composed in musical forms corresponding to the poetry they set, which were in the so-called formes fixes of rondeau, ballade, and virelai. These forms significantly affected the development of musical structure in ways that are felt even today; for example, the ouvert-clos rhyme-scheme shared by all three demanded a musical realization which contributed directly to the modern notion of antecedent and consequent phrases. 43 The Middle Ages – Ars Nova It was in this period, too, in which began the long tradition of setting the mass ordinary. This tradition started around mid-century with isolated or paired settings of Kyries, Glorias, etc., but Machaut composed what is thought to be the first complete mass conceived as one composition. The sound world of Ars Nova music is very much one of linear primacy and rhythmic complexity. "Resting" intervals are the fifth and octave, with thirds and sixths considered dissonances. Leaps of more than a sixth in individual voices are not uncommon, leading to speculation of instrumental participation at least in secular performance. 44 Ars Nova – Guillaume de Machaut Guillaume de Machaut, (c. 1300 – April 1377) Most significant composer of the Ars Nova Machaut's poetry was greatly admired and imitated by other poets including the likes of Geoffrey Chaucer. Machaut was and is the most celebrated composer of the 14th century He composed in a wide range of styles and forms and his output was enormous. Machaut was especially influential in the development of the motet and the secular song (particularly the lai, and the formes fixes: rondeau, virelai and ballade). Machaut wrote the Messe de Nostre Dame, the earliest known complete setting of the Ordinary of the Mass attributable to a single composer, and influenced composers for centuries to follow. 45 Notre Dame Mass –mid 13th Century Machaut’s Notre Dame Mass, one of the finest compositions known from the Middle ages, is also of great historical importance: it is the first polyphonic treatment of the mass ordinary by a known composer. Ordinary of the Mass Kyrie • Lord have mercy Gloria • Glory to God in the Highest Credo • I believe in One God Sanctus • Holy, Holy, Holy Agnus Dei • Lamb of God 48 Notre Dame Mass –mid 13th Century Music Example: Agnus Dei, from the Notre Dame Mass • A B Agnus Dei • Agnus Dei • • Triple meter Solemn and elaborate Complex rhythmic patterns contribute to its intensity Two upper parts are rhythmically active and contain syncopation, a characteristic of the 14th Century The two lower parts move in longer notes and play a supportive role Based on a Gregorian Chant, which Maucaut furnished with new rhythmic patterns and placed in the tenor, one of the two lower parts Since the chant, or cantus firmus, is rhythmically altered within a polyphonic web, it is more a musical framework than a tune to be recognized The harmonies of the Agnus Dei include stark disonances, hollow-sounding chords, and full triads Agnus Dei • • • • A 49 Notre Dame Mass –mid 13th Century B Agnus Dei A Agnus Dei Agnus Dei Music Example: Agnus Dei, from the Notre Dame Mass A A Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi: miserere nobis Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world: have mercy on us. B Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi: miserere nobis. Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world: have mercy on us. A Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi: dona nobis pacem. Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world: grant us piece 50