The Emotional Work of Care:

Inequalities in Capitals and Mothers’

Emotional Labour in Education

1

Concerns of this Paper

To focus on the significance of caring in the educational fieldparticularly, to highlight the nature of mothers’ involvement in

children’s education as a form of gendered moral care work and

to bring it from private consideration into public debate

To describe the educational care work done by mothers at

school transfer relative to different social positionings, and to

discuss the tensions between the idiosyncratic nature of this

care and the normalised expectations of care institutionalised

within the educational system

To explain the relationship between the gender inequality

associated with the allocation of this care to mothers, and the

inequalities between mothers relative to their capacities to

access and activate sets of resources or capitals

2

Theoretical FrameworkEmotional Care Work and Inequalities

Interdisciplinary discourse used to problematise the concept of

care and how it applies in the educational field. Lynch (1989) on

love labour as a form of uncommodifiable care work. Caring for

and about (Ungerson 1990), emotional work and intimate

relationships (Duncombe and Marsden 1993, 1996, 1998),

Hochschild (1983, 1989) on emotional management and

gendered relations.

Feminist moral philosophers on care and its centrality to moral

dispositions and behaviour - (Nussbaum 1995 2001, Bubeck,

1995, Sevenhuijsen 1998)

3

Mothers’ Care and the

Educational Field

A reductionist and gender biased discourse of parental

involvement (David et al. 1993, Reay 1998, 2000) Feminist

sociological interest in ‘school choice’ at transfer (David et al.

1994, Reay and Lucey 2000, Reay 2000, O’Brien 2001)

Mothering/caring work in education generally (Lareau 1989,

Smith 1996, Walkerdine and Lucey 1989, Plummer 2000,

Skeggs 1998, Smith 2005).

This paper draws on Bourdieu’s thesis of capitals in the context

of the production and (re)production of care, and Allatt’s

expansion of the idea of ‘emotional capital’ as educational

advantage.

4

Context for this Research-Mothers’

Emotional Care Work at School Transfer

(O’Brien 2005)

Based on a PhD study examining care work of twenty

five mothers at school transfer, chosen by theoretical

sampling- social class, marital status, ethnicity,

engagement in paid work, sexual orientation and

recently migrated.

Study sought to explore the nature of emotional care

work, its problematics and tensions relative to various

positionings, and to understand the meaning this

work held for mothers.

5

Mothers in Sample by Category

(marr=married, co-hab=cohabiting, sep=separated, al single=always single)

Full

time/Part

time/Fas

Child’s

educational

needs

Group/class

Marr,co-hab, Paid

sep, al

Work/not

single

Middle class

14

9,2,2,1

(2 lesbian, 1

sep, 1 cohab)

10

8,2,-

4

Workingclass

7

3,2,1,1

6

-,3,3

1

Traveller

2

1,1,-,-

1

-,-,1

1

Immigrant

2

2,-,-,-

0

-,-,-

-

N=25

N=25

N=17

N=17

N=6 6

Capitals and the Production of Care in

Education

Key FindingsThe significant issue of resources and capitals available to do

this gendered care work

-care is not naturally or magically produced, it is shaped and

indeed constrained by economic, cultural, social and emotional

capitals in the educational field. As Bourdieu has suggested

these are interrelated resources.

Emotional capital is understood as those internal emotional

resources and/or emotional supports accessed through personal

emotional support of an intimate or friend. A capital produced

through emotional connection and emotional recognition. (and

not necessarily through heterosexual marriage!)

Limitless care and/or lack of other resources depletes emotional7

capital daily and well-being.

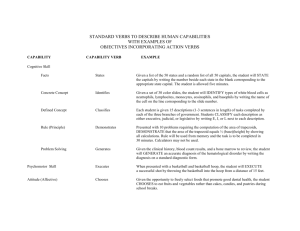

Figure 1 The Moral Encoding of Mothers’ Emotional Work

The Cognitive Order

: Gender Ideologies

A

B

E2

School Work:

Researching,

Phoning,

Deciding,

Meeting

Teachers,

Organising,

Homework,

Listening, Exam

Support,

Transporting,

Extra Curricular

Understandings of Emotional Work :

Mothers’ Narratives of love, ambivalence,

inalienability of care, essentialist and feminist

positions

The Moral Order :

The Moral Imperative to Care.

Mothers’ Habitus :

E1

C

Social Positionings :

Social Practices and Dispositions Class, Race, Ethnicity, Sexual

Relative to Positionings

Orientation, Paid Work

D

General

Emotional

Work:

Listening,

Feeding,

Supporting,

Thinking,

Talking,

Worrying,

Transporting,

Managing

Capacity to Access and Activate Capitals

The Resources Order : Forms

of Capital

Economic Capital

Cultural Capital

Social Capital

Emotional Capital

F

FAMILY CONTEXT

SCHOOL CONTEXT

8

TIME

The Resources Order and Care:

Categorising Capitals

(Bourdieu 1984 and Allatt 1993)

Economic capital-assigned a value 1-4, income rated v. low to

high based on < 29,000, low 29,000-I+25%, adequate I x 2, >

high I x 2.

Credentialised cultural capital 1-4- Educational qualifications on

continuum v. low to high based on v low, primay level, low junior

cert., adequate leaving cert. and high college degree.

Social Capital-social groups, neighbours and friends that can

give social advantage

Emotional capital 1-4: Intimate emotional supports available to

mother

9

Name

Economic Capital

Cultural Capital

Social Capital

Emotional Capital

Masha

Ellie

Brigid

Maisie

Kay

Nuala

Doreen

Linda

Kate

Ruth

Sarah

Janet

Anna

Rita

Pauline

Val

Trudi

Rose

Laura

Donna

Marie

Maura

Connie

Noreen

Nell

1

1

1

1

2

2

1

3

3

3

4

3

3

2

1

1

3

2

2

3

4

4

3

4

3

3

3

1

1

1

2

2

4

4

4

3

4

4

4

1

1

4

2

1

3

4

3

3

4

3

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

3

2

3

3

2

4

3

1

1

3

2

2

3

4

3

3

4

3

1

1

2

2

3

2

2

2

2

3

2

3

4

3

1

2

3

2

2

3

3

3

2

3

3

10

Patterns of Economic and Cultural Capital

4.5

4.5

4

4

3.5

3.5

3

3

25

23

21

19

17

15

13

11

25

22

19

0

16

0

13

0.5

10

1

0.5

7

1

4

1.5

1

1.5

Cultural Capital

9

2

7

Economic Capital

Economic Capital

5

2

2.5

3

Cultural Capital

1

2.5

11

Relationships between Capitals

4.5

4.5

4

4

3.5

3.5

3

3

4.5

4.5

4

4

3.5

3.5

3

3

25

22

1

25

22

19

16

0

13

0.5

0

10

1

7

1

0.5

19

1.5

4

Cultural Capital

16

1.5

1

Economic Capital

2

13

Economic Capital

10

2

2.5

7

Cultural Capital

4

2.5

25

25

22

0

19

0

16

0.5

13

0.5

10

1

7

1

4

1.5

1

1.5

22

Emotional Capital

19

2

16

Economic Capital

13

2

10

Economic Capital

7

2.5

4

Emotional Capital

1

2.5

12

Accessing and Activating Capitals

Resources are not automatically translated into a product-care (Lareau

et al. 1999, Reay 2000) ! It takes effort, time and energy to activate

these capitals to benefit the child.

IdiosyncrasyMothers’ positioning and habitus-Anna whose sexual orientation meant

difficulties activating cultural capital in the educational field

Problems of paid work

Time away from care in paid work may increase mothers emotional

capital and capacity to care

Marginality

Masha from Dubai and Ellie found it not posssible to access the full

potential of this capital from their marginal positionings and relative to

the lack of economic and emotional resources they experienced at this

time in Ireland.

13

Specifics of Capitals and School

Transfer

Economic Capital-is required for school fees, subscriptions,

uniforms, books and equipment, extracurricular activities,

transport and hidden day to day schooling costs

-no money no choice: I wouldn’t have the money for the other school

either because their books are too expensive, here you can rent…..

-having money means choices

But…Having choices can mean more emotional work (Ruth),

Cultural capital-seems to be the capital par excellence in

discerning and supporting academic work-example of Traveller

women. But moral care sometimes requires mothers to use

cultural capital in unexpected resistances to schooling for the

child’s happiness (Anna) or because of wider familial demands

(Janet, Marie)

Social capital- ‘pressing those buttons’ to gain access to

schools, various forms of social capital in context. Being a

14

teacher, an insider. Ellie talks of her lack of social capital.

Emotional Capital and how is it accessed

and used in care?

A gendered capital: Our emotional energy and skills to care for

ourselves, and those we are in relationship with. Resilience,

positivity, connectedness, empathy used through time and to

make time to care.

Interrelated with other capitals-but could have money, friends

and education and still feel low-illness, depression,

bereavement, unemployment, separation. Running on empty!

But not quite and not allowed to not care (or children may be

taken into care-Brigid’s experience as a Traveller).

Emotional capital maintains the circle of care (Bubeck 1995)being tied to the inalienable work of care even when they lack

this basic resource-creates frustration, guilt and feelings of

inadequacy. Facilitates one’s sense of identity as a moral person

15

“finding the crock of gold”. Emotional capital links one to the

Figure 1 Spatial Metaphor: Mapping Mothers’

Access to Capitals

MASHA

ELLIE

EC

BRIGID

4

MAISIE

KAY

3

NUALA

DOREEN

LINDA

2

KATE

RUTH

SARAH

1

JANET

ANNA

EMC

CC

0

RITA

PAULINE

VAL

TRUDI

ROSE

LAURA

DONNA

MARIE

MAURA

CONNIE

NOREEN

SC

NELL

16

Figure 2 Spatial Metaphor Contrasting Capitals for

Pauline (Working Class) and Anna (Middle Class)

Contrasting Capitals

EMC

EC

4

3

2

1

0

CC

Anna

Pauline

SC

17

Conclusions? -Tackling Inequalities in

Emotional Care

Is justice then a question of redistribution of capitals?

Partly, yes, in that inequalities between women make it difficult

to care and impact on their well-being and their families..time,

money…

How or can emotional capital be redistributed?

Mothers’ emotional capital can be increased through less stress

of absence of other capitals. The question is how to increase

caring connections and that is more a political problem and of

making care central to life in all contexts (Fraser 2000,

Hochchild 1995).

18

Tackling Care Inequalities

contd.

Is redistribution of capitals sufficient for equality in care?

No, because activating capitals to do care work is subject to

positionings, and inequalities of recognition, and to

idiosyncrasies that arise from these. Moreover, issues of

respect and power are fundamental -tackling patriarchal

familial relations but how?

Tackling care inequalities must also be about gender ideology

and inequality as they have been institutionalised, as the

resources order and moral and gendered orders are linked.

Instances of ambivalence in women’s narratives showed that

being tied to intensive care even when one has the resources to

carry out the work means one’s development and well-being as

a woman are curtailed. So build up men’s emotional capital? 19