BF Skinner's Analysis of Verbal Behavior

advertisement

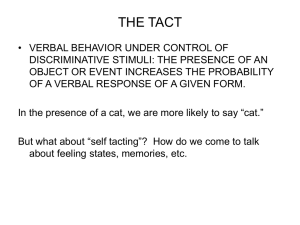

B. F. Skinner’s Analysis of Verbal Behavior Mark L. Sundberg, Ph.D., BCBA (www.marksundberg.com) Alfred North Whitehead and “No Black Scorpion” • We dropped into a discussion of behaviorism which was then still very much an “ism” and of which I was a zealous devotee [1934]. Here was an opportunity which I could not overlook to strike a blow for the cause....Whitehead... agreed that science might be successful in accounting for human behavior provided one made an exception of verbal behavior. Here, he insisted something else must be at work. He brought the discussion to a close with a friendly challenge: “Let me see you,” he said “account for my behavior as I sit here saying ‘No black scorpion is falling upon this table.’” The next morning I drew up the outline of the present study (Skinner, 1957, p. 457). What is Language? • • • • • • • What constitutes “Language?” How do we talk about it? How do we measure it? What are its parts? How do we assess it? How do we teach it? There are many different theories of language. Theories of Language • • • • • • In Chapter 1 of Verbal Behavior Skinner presents the various linguistic theories Linguistic theory can be classified into three general, and often overlapping views: biological, cognitive, and environmental Proponents of the biological view (e.g., Chomsky, 1965; Pinker, 1994) argue that language is innate to humans and primarily a result of physiological processes and functions, and that language has little to do with environmental variables, such as reinforcement and stimulus control Brain------->Words, phrases, sentences Nature vs. nurture No current applications of Chomsky or Pinker to autism Theories of Language • • • • Cognitive psychologists argue that language is controlled by internal cognitive processing systems that accept, classify, code, encode, and store verbal information (e.g., Brown, 1973; Piaget, 1926; Slobin, 1973), and language has less to do with environmental variables, such as reinforcement and stimulus control Language is viewed as receptive and expressive, and the two are referred to as communicative behavior that is controlled by cognitive processors Cognition------>Words Cognitive theory, and its receptive-expressive framework dominates the current language assessment and intervention programs for children with autism How is Language Measured in a Traditional Linguistic Analysis? • • • • • • • • • The focus is on response forms, topography, and structure Phonemes Morphemes Lexicon Syntax Grammar Semantics Mean length of utterances (MLU); words, phrases, sentences Classification system: nouns, verbs, prepositions, adjectives, adverbs, etc. Skinner’s (1957) Book Verbal Behavior • • • • Chapter 1 of Verbal Behavior is titled “A Functional Analysis of Verbal Behavior” Etymological sanctions and terminology in VB Language is learned behavior under the functional control of environmental contingencies “What happens when a man speaks or responds to speech is clearly a question about human behavior and hence a question to be answered with the concepts and techniques of psychology as an experimental science of behavior” (Skinner, 1957, p. 5) Skinner’s (1957) Book Verbal Behavior • • • • Definition of verbal behavior: “Behavior reinforced through the mediation of other persons” (who are trained to do so) A distinction between the speaker and the listener (“The total verbal episode”). The speaker and listener can be in the same skin Form and function “Our first responsibility is simple description: what is the topography of this subdivision of human behavior? Once that question has been answered in at least a preliminary fashion we may advance to the stage called explanation: what conditions are relevant to the occurrences of the behavior--what are the variables of which it is a function?” (p. 10). Skinner’s (1957) Book Verbal Behavior • • The analysis of verbal behavior involves the same behavioral principles and concepts that make up the analysis of nonverbal behavior. No new principles of behavior are required. There are some new terms In Chapter 2 of VB Skinner presents the independent and dependent variables of verbal behavior A Functional Analysis of Verbal Behavior: The Basic Principles of Operant Behavior Stimulus Control (SD) Motivating Operation (MO/EO) Response Reinforcement Punishment Extinction Conditioned reinforcement Conditioned punishment Intermittent reinforcement Skinner’s (1957) Book Verbal Behavior • • • • “Technically, meanings are to be found among the independent variables in a functional account rather than as properties of the dependent variable” (p. 14) What constitutes a “unit of verbal behavior?” (sounds, words, phrases, sentences) “...a response of identifiable form functionally related to one or more independent variables” (p. 20) In Chapter 2 of VB Skinner also presents a VB research methodology and suggests several advantages of using his analysis of verbal behavior as a foundation for language research Skinner’s (1957) Book Verbal Behavior • • • • A common misconception about Skinner’s analysis of verbal behavior is that he rejects the traditional classification of language However, it is not the traditional classification or description of the response he finds fault with, it is the failure to account for the causes or functions of the verbs, nouns, sentences, etc. The analysis of how and why one says words is typically relegated to the field of psychology combined with linguistics; hence the field of “psycholinguistics” Skinner noted that “A science of behavior does not arrive at this special field to find it unoccupied” (p. 3) How is Language Measured in a Behavioral Analysis? The verbal operant is the unit of analysis (e.g., mands, tacts, & intraverbals) MO/SD Response Consequence Skinner’s Analysis of Verbal Behavior • • The traditional linguistic classification of words, sentences, and phrases as expressive and receptive language blends important functional distinctions among types of operant behavior, and appeals to cognitive explanations for the causes of language behavior (Skinner, 1957, Chapters 1 & 2) In Chapters 3-5 of Verbal Behavior Skinner presents the “elementary verbal operants” Skinner’s Analysis of Verbal Behavior • • • • • • At the core of Skinner’s analysis of verbal behavior is the distinction between the mand, tact, and intraverbal (traditionally all classified as “expressive language”) Skinner identified three separate sources of antecedent control for these verbal operants EO/MO control------->Mand Nonverbal SD--------->Tact Verbal SD-------------->Intraverbal Established body of empirical support for this distinction (Sautter & LeBlanc, 2006) The Behavioral Classification of Language • • • • • Four of the verbal operants… Mand: Asking for reinforcers. Asking for “Mommy” because a child wants his mommy Tact: Naming or identifying objects, actions, events, etc. Saying “Mommy” because a child sees his Mommy Echoic: Repeating what is heard. Saying “Mommy” after someone else says “Mommy” Intraverbal: Answering questions or having conversations where the speaker’s words are controlled by other words. Saying “Mommy” because someone else says “Daddy and...” The Distinction Between the Mand and the Tact • • • • Based on the distinction between the establishing operation (EO/MO) and stimulus control (SD) as separate sources of control Skinnerian psychology (“radical behaviorism,” see Skinner, 1974) has always maintained that motivational control is different from stimulus control In Behavior of Organisms (Skinner, 1938) Skinner devoted two chapters to the treatment of motivation; Chapter 9 titled “Drive” and Chapter 10 titled “Drive and Conditioning: The Interaction of Two Variables” Skinner also made it clear in the section titled “Drive (is) Not a Stimulus” (pp. 374-376) that motivation is not the same as discriminative, unconditioned, or conditioned stimuli The Distinction Between the Mand and the Tact • • • Keller and Schoenfeld (1950) titled Chapter 9 “Motivation” and further developed Skinner’s point, “A drive is not a stimulus” (p. 276), and suggested “a new descriptive term... ‘establishing operation’” (p. 271) In Science and Human Behavior (1953) Skinner devoted three chapters to motivation: Chapter 9: “Deprivation and Satiation,” Chapter 10: “Emotion,” and Chapter 11: “Aversion, Avoidance, Anxiety” In Verbal Behavior (1957) Skinner had a full chapter on motivation and language (The Mand), and throughout the book provided many elaborations on motivational control -- as an antecedent variable Motivative Operations (MO) and Stimulus Control (SD) • • • • • The definition (Michael, 2007) of an MO: (a) an environmental event that increases the momentary effectiveness of anything as a form of reinforcement, and (b) increases the frequency of any behavior that has been followed by that form of reinforcement in the past The definition (Michael, 1982) of stimulus control (SD): a particular stimulus that evokes a particular behavior due to a history of reinforcement MO: SR/Sr are effective (Do you want it now?) SD: SR/Sr are available (Can you get it now?) See Martinez-Diaz (2006) for an excellent PowerPoint tutorial on the distinction between the SD and MO The Mand Relation MO/EO Child wants the Dora video Response “Dora” Specific Reinforcement “Here it is” Examples of Mands • • • • • • • • • • Mine! I want my mommy! Come on. Go away. Open it. Who is that? How does this work? Are we there yet? How is an MO different from an SD? How do you know if these are mands? The Importance of the Mand • • • • Mands are the first type of verbal behavior acquired by typical children Manding allows a child to get what he wants, when it is wanted Manding allows a child to get rid of what he does NOT want, when it is not wanted A parent or caretaker is paired with the delivery of reinforcement related to a mand The Importance of the Mand • • • • Manding brings about desired changes or conditions Manding allows a child to control the social environment Manding is the only verbal operant that directly benefits the speaker Manding training can decrease negative behaviors that serve the mand function The Importance of the Mand • • • • Mand training helps to establish speaker as well as listener rolls For early learners, mands do not emerge by training on the other verbal operants Mand trials can be used as reinforcers for other forms of verbal behavior Manding is essential for social interaction The Importance of the Mand • • • • Manding allows a speaker to acquire new information and new forms of verbal behavior Neglect of the mand can impair language development Neglect of the mand can result in emotional impairment Excessive manding is a burden on the listener Issues Concerning Motivative Operations (MOs) and Mands • • • • • All mands are controlled by motivating operations There must be an MO at strength to conduct mand training MOs vary in strength across time, and the effects may be temporary MOs must be either captured or contrived to conduct mand training MOs may have an instant or gradual onset or offset Issues Concerning Motivative Operations (MOs) and Mands • • • • High response requirement may weaken an MO Instructors must be able to identify the presence and strength of an MO Instructors must be able to reduce existing negative behavior controlled by MOs Instructors must know how to bring verbal behavior under the control of MOs The Tact Relation Nonverbal SD Child sees a poster of Dora Response “Dora” Generalized Reinforcement “It is Dora” The Tact Relation • • • • Tacts are always under nonverbal stimulus control Nonverbal discriminative stimuli involve: “nothing less than the whole of the physical environment--the world of things and events which a speaker is said to “talk about.” Verbal behavior under the control of such stimuli is so important that it is often dealt with exclusively in the study of language and in theories of meaning” (Skinner, 1957, p. 81). Nonverbal stimuli can be, for example, static (nouns), transitory (verbs), relations between objects (prepositions), properties of objects (adjectives), or properties of actions (adverbs) The Tact Relation • • • • Different sense modes (“contact with the physical environment”) Tacts can be controlled by nonverbal discriminative stimuli arising from, for example, visual, auditory, olfactory, gustatory, tactile, kinisthetic, pain, and chemo receptors In order for a nonverbal stimulus to become a discriminative stimulus for a tact there must be some process of operant conditioning The consequences for the tact involve generalized conditioned reinforcement Examples of Tacts • • • • • • • • • • • There’s mommy It’s a car He laughing I see red I feel sick That is a 57 Chevy That’s inappropriate behavior Those guys are fast Were going up I smell gas What would it take to make these same responses mands? The Echoic Relation Verbal SD W/pt-pt correspondence Response Formal similarity Child hears “Dora” “Dora” Generalized Reinforcement “Right” The Echoic Relation • • • Verbal stimulus control: “Product of someone’s verbal behavior functions as a discriminative stimulus” (Michael, 1982) Point -to-point correspondence: “subdivisions or parts of the stimulus control subdivisions or parts of the response” (Michael, 1982) Formal similarity: “the controlling stimulus and the response product are (1) in the same sense mode (both are visual, or both are auditory, or both are tactile, etc.) and (2) resemble each other in the physical sense of resemblance” (Michael, 1982, p. 2)” The Echoic Relation • • • • • • Motor Imitation Motor imitation can have the same verbal properties as echoic behavior, as demonstrated by its role in the acquisition of sign language by children who are deaf Copying-a-text also has the same defining properties as the echoic Michael (1982) suggested the term “duplic” for these three verbal relations The consequences for the echoic involve generalized conditioned reinforcement The ability to echo the phonemes and words of others is essential for learning to identify objects and actions The echoic consists of a “minimal repertoire” The Intraverbal Relation Verbal SD W/o pt-pt correspondence Response W/o Formal similarity Child hears “Who is your favorite doll?” “Dora” Generalized Reinforcement “Of course!” The Intraverbal Relation • • • NO Point -to-point correspondence: The verbal stimulus and the verbal response do not match each other, as they do in the echoic relation. NO Formal similarity: the controlling stimulus and the response product can be in the the same or different sense modes and DO NOT resemble each other in the physical sense of resemblance Like all verbal operants except the mand, the consequences for the intraverbal involve generalized conditioned reinforcement (Skinner also uses “non-specific reinforcement,” “educational reinforcement,” and “contiguous usage” to identify the consequences for the intraverbal The Intraverbal Relation • • • • • Verbal behavior evoked by other non-matching verbal behavior It prepares a speaker to behave rapidly and accurately with respect to verbal stimulation, and plays an important role in continuing a conversation There is a huge variation in speaker’s intraverbal repertoires, especially when compared to the mand and the tact Typical adult speakers have hundreds of thousands of intraverbal relations as a part of their verbal repertoires An intraverbal repertoire allows a speaker to answer questions and to talk about (and think about) objects and events that are not physically present What is Intraverbal Behavior? • • An intraverbal repertoire facilitates the acquisition of other verbal and nonverbal behavior Intraverbal behavior is a critical part of many important aspects of human behavior such as social interactions, intellectual behavior, memory, thinking, problem solving, creativity, academic behavior, history, and entertainment Examples of Intraverbal Behavior Emitted by Children Verbal Stimulus Twinkle twinkle little... A kitty says... Mommy and... Knife, fork and... What do you like to eat? What’s your favorite movie? Can you name some animals? What’s your brother’s name? Where do you go to school? Verbal Response Star Meow Daddy Spoon Pizza! Sponge Bob Square Pants! Dog, cat, and horse Charlie Harvest Park Examples of Adult Intraverbal Behavior Verbal Stimulus How are you? What’s your name? Where do you live? What do you do? What is ABA? What do I do about SIB? Should I attend Dr. Iwata’s talk? Is there research to support ABA? Verbal Response I am fine. Mark Concord, CA I’m a behavior analyst... B F. Skinner... The first step... Yes, Dr Iwata... Yes, there is... How is the Intraverbal Relation Different from the Mand, Tact, & Echoic? • • • • • Antecedent Motivation (EO) Nonverbal SD Verbal SD with a match Verbal SD without a match Behavior Consequence Mand Tact Echoic Specific reinf. Social reinf. Social reinf. Intraverbal Social reinf. The Behavior of the Listener • • A major theme in Verbal Behavior is the focus on the speaker, rather than the listener. Skinner (1978) pointed out that: “linguists and psycholinguists are primarily concerned with the behavior of the listener--with what words mean to those who hear them and with what kind of sentences are judged grammatical or ungrammatical. The very concept of communication--whether of ideas, meanings, or information--emphasizes transmission to a listener. So far as I am concerned, however, very little of the behavior of the listener is worth distinguishing as verbal (p. 122).” The Behavior of the Listener • • Skinner (1957) also notes that: “The traditional conception of verbal behavior discussed in Chapter 1 has generally implied that certain basic linguistic processes were common to both speaker and listener. Common processes are suggested when language is said to arouse in the mind of the listener “ideas present in the mind of the speaker,” or when communication is regarded as successful only if an expression has “the same meaning for both speaker and listener.” Theories of meaning are usually applied to both speaker and listener as if the meaning process were the same for both. Much of the behavior of the listener has no resemblance to the behavior of the speaker and is not verbal according to our definition” (p. 33) The Behavior of the Listener • • • • • • • • The listener plays a critical role in consequating a speaker’s behavior Attention (e.g., eye contact, body position) Social reinforcement (head nods, praise, body positions) Mediator of reinforcement (e.g., responding to the mands of speakers by getting things, opening doors, and other nonverbal behavior) Social punishment (e.g., frowns, head nods, body position, look away) Extinction (e.g., ignore) The listener is also an SD and an MO for a speaker’s behavior Skinner devotes a full chapter to this role of the listener as an “audience” for verbal behavior (1957, chap. 7) The Behavior of the Listener “The listener, as an essential part of the situation in which verbal behavior is observed, is again a discriminative stimulus. He is part of an occasion upon which verbal behavior is reinforced and he therefore becomes part of the occasion controlling the strength of the behavior. This function is to be distinguished from the action of the listener in reinforcing behavior....An audience, then, is a discriminative stimulus in the presence of which verbal behavior is characteristically reinforced and in the presence of which, therefore, it is characteristically strong” (p. 172). • The Behavior of the Listener • • • • • • When a speaker talks to a listener verbal stimuli are emitted that are discriminative stimuli The question is what are the effects of verbal SDs on listener behavior? Skinner (1957, p. 277-280) identifies two main effects of verbal SDs: Verbal stimuli evoke specific nonverbal behavior, and they evoke specific verbal behavior When verbal stimuli evoke nonverbal behavior the behaver is still functioning as a listener, but is differentially discriminating among verbal stimuli (commonly called receptive language, RFFC) “The listener can be said to understand a speaker if he simply behaves in an appropriate fashion” (p. 277). The Behavior of the Listener • • • A verbal discriminative stimulus can also evoke echoic, textual, transcriptive, or intraverbal behavior on the part on a listener. However, if this occurs, the listener becomes a speaker, which is Skinner’s point that “in many important instances the listener is behaving at the same time as a speaker” (p. 33, footnote) The most significant and complex responses to verbal stimuli occur when they evoke covert intraverbal behavior from a listener (who by definition, is now a speaker who serves as his own audience) Skinner devotes a full chapter to the topic of “thinking” in Science and Human Behavior (1953, chap. 16), Verbal Behavior (1957, Chap. 19) and About Behaviorism (1974, chap. 7), and he has several sections dedicated to the topic of “understanding,” (e.g., pp. 277280; Skinner 1974, 141-142) Listener Discrimination Verbal SD “Get the Dora video” Response Child’s selects Dora video Generalized Reinforcement “That’s it!” The Textual Relation Verbal SD W/pt-pt correspondence Response W/o Formal similarity Child sees “Dora” written “Dora” Generalized Reinforcement “Right” The Textual Relation • • • Verbal stimulus control Point-to-point correspondence No formal similarity: The controlling stimulus and the response product are not in the same sense mode and do not resemble each other The Transcriptive Relation Verbal SD W/pt-pt correspondence Response W/o Formal similarity Child hears “Dora” spoken Writes “Dora” Generalized Reinforcement “Right” The Transcriptive Relation • • • Verbal stimulus control Point-to-point correspondence No formal similarity: The controlling stimulus and the response product are not in the same sense mode and do not resemble each other Verbal Extensions • • • • Generalization “If a response is reinforced upon a given occasion or class of occasions, any feature of that occasion or common to that class appears to gain some measure of control” (p. 91) A novel stimulus possessing one such feature may evoke a response (p. 91) There are several ways in which a novel stimulus may resemble a stimulus previously present when a response was reinforced, and hence there are several types of what we may call “extended tacts” (p. 91). Verbal Extensions • • • • • Skinner distinguished between four types of extended tacts generic, metaphoric, metonymic, and solistic The distinction is based on the degree to which a novel stimulus shares the relevant or irrelevant features of the original stimulus In generic extension, the novel stimulus shares all of the relevant or defining features of the original stimulus. In metaphorical extension the novel stimulus shares some, but not all of the relevant features of the original stimulus Metonymical extensions involve responses to novel stimuli that have none of the relevant features of the original stimulus configuration, but some irrelevant but related feature has acquired stimulus control Verbal Extensions • • Finally, a solistic extension occurs when “ The property which gains control of the response is only distantly related to the defining properties upon which standard reinforcements are contingent or is similar to that property for irrelevant reasons....Most verbal communities not only fail to respond effectively to such extensions but provide some sort of punishment for them” (p. 102) Multiple Control • • • • Parts I and II of the book Verbal Behavior provide the reader with the defining features of the elementary verbal operants and many examples of these operants Parts III, IV, and V focus on how to use these operants to analyze complex verbal behavior Any given sample of verbal behavior, especially those involving verbal exchanges between speakers and listeners, contains a multitude of functional relations between antecedents, behavior, and consequences The functional units of echoic, mands, tacts, intraverbals, and textual relations form the foundation of a verbal behavior analysis Multiple Control • • • • “Two facts emerge from our survey of the basic functional relations: (1) the strength of a single response may be, and usually is, a function of more than one variable, and (2) a single variable usually affects more than one response” (1957, p. 227) Michael (2003) identifies conditions where the strength of a single verbal response is a function more than one variable as “convergent multiple control.” Convergent multiple control can be observed in almost all instances of verbal behavior. MOs, nonverbal stimuli, and verbal stimuli frequently share antecedent control over verbal behavior Multiple Control • • • • • • Convergent multiple control SD SD SD SD MO R Multiple Control • • • The second type of multiple control identified by Skinner occurs when a single antecedent variable affects the strength of more than just one response “Just as a given stimulus word will evoke a large number of different responses from a sample of the population at large, it increases the probability of emission of many responses in a single speaker” (p. 227) Michael (2003) identifies this type of control “divergent multiple control” Multiple Control • Divergent multiple control • • SD/MO • • R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 Thank You! For an electronic version of this presentation visit: www.marksundberg.com