Cherokee Nation versus Georgia

advertisement

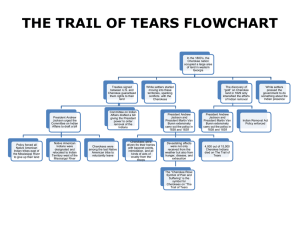

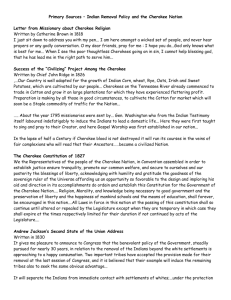

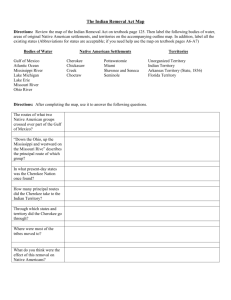

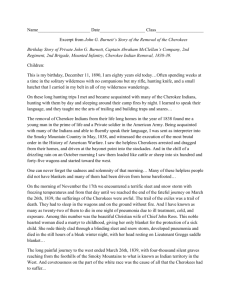

Indian Removal The presence of Native Americans represented a challenge or impediment to westward expansion. To the growing white majority of the Western frontier, the presence of any Indians at all, “civilized” or not, was unacceptable. While white planters and land speculator continued to pour in, hungry for new acreage on which to raise cotton and expand the slave system, and relentlessly pressed the federal government to remove the Cherokee as well as the other Southeastern tribes and open their territories to settlement, every perceived failing was dredged up to discredit the Cherokee. The crisis for removal reached a crescendo following the discovery of gold on the edge of Cherokee territory in 1828. The “Indian Problem” The first option was genocide (extermination)—no doubt some contemporary Americans agreed with Henry Clay who said in 1825 that the disappearance of the Indian “from the human family will be no great loss to the world.” Fortunately, no one in the Jackson administration never advocated exterminating Native Americans, rather viewing it as unthinkable. As for the second option—assimilation—neither Indians nor whites favored it. Most whites were racist and regarded Indians as inferior exhibiting either fear or outrage at the thought of miscegenation. Furthermore, Native Americans wished to preserve their unique identity as a people, having their own laws, religion, constitution, and society. Assimilation meant becoming cultural white people—a prospect they totally rejected. The third option, military protection, was an utter impossibility considering the greed and avarice with which Americans coveted Indian land—land that would have been taken regardless since it would have taken an armed force larger than anything available to the government at the time to keep whites out of Indian territory. Removal, which probably originated with Thomas Jefferson and was the option the Jackson administration adopted, was, according to Jackson, the only policy to pursue if Indian tribes and their culture were to survive. According to one twentieth century historian of Native Americans, Francis Paul Prucha (right), the United States government had little choice in its policy toward the Indians. Of the four courses of action open, the only viable option was removal since each of the remaining three options posed certain problems. Hindsight will show that those tribes that did remove exist today whereas other tribes in the east disappeared. Nonetheless, removal (as implemented) proved to be a ghastly price to pay for the survival of Native Americans. Removal The idea of removal was not a new one—Thomas Jefferson, among others, had advocated moving all Indians west of the Mississippi River until they became accustomed to white ways. In his Annual Message to Congress in 1817, President James Monroe called for the removal of Indians, arguing the hunter should make way for the farmer. Indian Bureau FROM 1824 TO 1830, THOMAS MCKENNEY SERVED AS SUPERINTENDENT OF INDIAN AFFAIRS. MCKENNEY’S TRANSACTIONS WITH THE “CIVILIZED” SOUTHERN TRIBES HAD, AT ONE TIME, PERSUADED HIM THAT INDIANS MIGHT BE ABLE TO ADOPT WHITE VALUES. AS TROUBLING AS SUCH EXPERIMENTS MUST APPEAR TO US, THE ALTERNATIVES, IN MCKENNEY’S VIEW, WERE FAR WORSE: INDIANS WHO DID NOT ASSIMILATE, OR MOVE BEYOND THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER, WERE DOOMED. IN 1829 MCKENNEY WROTE: “WE BELIEVE IF THE INDIANS DO NOT EMIGRATE, AND FLY THE CAUSES, WHICH ARE FIXED IN THEMSELVES, AND WHICH HAVE PROVED SO DESTRUCTIVE IN THE PAST, THEY MUST PERISH!” IN 1830 THE JACKSON ADMINISTRATION DISMISSED MCKENNEY FOR NOT BEING IN SUFFICIENT HARMONY WITH ITS INDIAN POLICY. BUT THE PREVAILING VIEW––THAT INDIANS MUST BE “CIVILISED” IF THEY WERE TO SURVIVE WAS APPARENTLY NOT IN DISPUTE. MCKENNEY APPEARS TO HAVE HOPED THAT THE RELOCATION OF THE INDIANS COULD BE ACHIEVED BY PERSUASION, WHILE JACKSON WAS DETERMINED TO USE FORCE. Thomas L. McKenney, 1856, by Charles Loring Eliot PRESIDENT JACKSON ALSO ORDERED THE WAR DEPARTMENT TO REMOVE THOSE INDIAN BOYS MCKENNEY BROUGHT TO HIS FARM, WESTON, ON GEORGETOWN HEIGHTS FOR SCHOOLING FROM SCHOOL, AND TO RETURN THEM TO THEIR PEOPLE. Andrew Jackson long advocated Indian removal west of the Mississippi River—Jackson considered this one of the most cherished goals on becoming President. Jackson became so certain that removal was the only answer to the Indian problem that upon his election as President he gave enactment of a removal bill the highest priority. Removal would (1) protect the American people by averting a further clash of cultures; (2) provide greater security for the U.S. by literally removing a potential fifth column in the event of an attack or invasion; (3) prevent the almost certain annihilation of Indian life and culture that would have occurred if Indian tribes remained within the jurisdiction of Eastern States; (4) remove obstacles and impediments to progress. Jackson objected to the existence of sovereign Indian nations within the boundaries of the United States, fearing they might make their own alliances with Spain or England, which still posed a real threat to America’s national ambitions. Removal SOUTHERN AND WESTERN BAPTISTS WERE ALSO FOR REMOVAL AND WERE LED BY CLERGYMAN ISAAC MCCOY OF INDIANA WHO TOURED THE EAST IN 1829 TO PROMOTE INDIAN REMOVAL. WITH GOOD INTENTIONS, MCCOY BEGAN IN 1823 TO ADVOCATE THAT THE INDIAN NATIONS OF THE EAST BE MOVED WEST "BEYOND THE FRONTIERS OF THE WHITE SETTLEMENT." HE BELIEVED THAT GETTING THE TRIBES TO THEIR OWN, ISOLATED PLACES, AWAY FROM THE REACH OF WHISKEY TRADERS AND OTHERS WHO WERE EXPLOITING THEM, WOULD GIVE THEM A BETTER CHANCE OF SURVIVING AND BECOMING CHRISTIANIZED. MCCOY'S IDEAS FOR REMOVAL OF THE INDIANS WERE NOT NEW, BUT HE PROMOTED THE IDEA THAT THE U.S. GOVERNMENT SHOULD FUND "CIVILIZATION PROGRAMS" TO EDUCATE THE INDIANS AND TURN THEM INTO FARMERS AND CHRISTIANS. MCCOY EXPANDED HIS CONCEPT LATER TO PROPOSE THE CREATION OF AN INDIAN STATE MAKING UP MOST OF THE LAND AREA OF KANSAS, OKLAHOMA, AND NEBRASKA. Andrew Jackson’s 1st Annual Message to Congress (1829) “HUMANITY AND NATIONAL HONOR DEMAND” THAT THE GOVERNMENT SAVE THE INDIANS FROM “WEAKNESS AND DECAY” BY SEPARATING THEM FROM WHITE MEN. JACKSON POINTED OUT THE CONTRADICTORY INDIAN POLICY OF THE UNITED STATES. ALTHOUGH COMMITTED TO ASSIMILATING INDIANS INTO WHITE AMERICAN CULTURE, SUCCESSIVE ADMINISTRATIONS ALSO NEGOTIATED DOZENS OF TREATIES IN WHICH INDIANS CEDED LAND AND RETREATED (I.E. REMOVED THEMSELVES) WEST. SINCE THE JEFFERSON ADMINISTRATION, PRESSURE MOUNTED TO REPLACE THIS PIECEMEAL POLICY (IN WHICH ONLY SELECT TRIBES WERE REMOVED) WITH A NEW PROGRAM THAT WOULD REMOVE ALL INDIANS OCCUPYING EASTERN LANDS TO THE WESTERN BANKS OF THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER. THERE WAS NO DOUBT WHERE JACKSON STOOD ON THE INDIAN QUESTION—LIKE MANY WHITE AMERICANS AT THE TIME, HE CONSIDERED THE INDIANS INFERIOR AND ASSUMED A PATERNALISTIC ATTITUDE TOWARD THEM. JACKSON APPOINTED STRONG SUPPORTERS OF INDIAN REMOVAL, SUCH AS EATON AND BERRIEN, TO IMPORTANT POSTS WITHIN HIS ADMINISTRATION WHILE PUBLICLY PRESSING THE CREEKS AND CHEROKEES TO MOVE WEST. JACKSON’S POLITICAL FRIEND, CARROLL, ASSERTED THAT THE PRESIDENT’S INDIAN POLICY WAS BOTH “CORRECT AND HUMANE” SINCE THE UNDISCIPLINED INDIANS WANTED NO PART OF WHITE RULE WHILE FURTHER POINTING OUT THAT THE INDIANS DID NOT LIKE THE WHIPPING POST AND THE OTHER “LAWS OF CIVILIZED SOCIETY.” Andrew Jackson’s 2nd Annual Message to Congress (1830) followed passage of the Indian Removal Act on May 28, 1830 and its acceptance by “two important tribes” (the act authorized congressional appropriations for the removal of the Five so-called “Civilized Tribes”) “THE CONSEQUENCES OF A SPEEDY REMOVAL WILL BE IMPORTANT TO THE UNITED STATES, TO INDIVIDUAL STATES AND TO THE INDIANS THEMSELVES. THE PECUNIARY ADVANTAGES WHICH IT PROMISES TO THE GOVERNMENT ARE THE LEAST OF ITS RECOMMENDATIONS. IT PUTS AN END TO ALL POSSIBLE DANGER OF COLLISION BETWEEN THE AUTHORITIES OF THE GENERAL AND STATE GOVERNMENTS ON ACCOUNT OF THE INDIANS. IT WILL PLACE A DENSE AND CIVILIZED POPULATION IN LARGE TRACTS OF COUNTRY NOW OCCUPIED BY A FEW SAVAGE HUNTERS. BY OPENING THE WHOLE TERRITORY BETWEEN TENNESSEE ON THE NORTH AND LOUISIANA ON THE SOUTH TO THE SETTLEMENT OF THE WHITES IT WILL INCALCULABLY STRENGTHEN THE SOUTHWESTERN FRONTIER AND RENDER THE ADJACENT STATES STRONG ENOUGH TO REPEL FUTURE INVASIONS WITHOUT REMOTE AID. IT WILL RELIEVE THE WHOLE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI AND THE WESTERN PART OF ALABAMA OF INDIAN OCCUPANCY, AND ENABLE THOSE STATES TO ADVANCE RAPIDLY IN POPULATION, WEALTH, AND POWER. IT WILL SEPARATE THE INDIANS FROM IMMEDIATE CONTACT WITH SETTLEMENTS OF WHITES; FREE THEM FROM THE POWER OF THE STATES; ENABLE THEM TO PURSUE HAPPINESS IN THEIR OWN WAY AND UNDER THEIR OWN RUDE INSTITUTIONS; WILL RETARD THE PROGRESS OF DECAY, WHICH IS LESSENING THEIR NUMBERS, AND PERHAPS CAUSE THEM GRADUALLY, UNDER THE PROTECTION OF THE GOVERNMENT AND THROUGH THE INFLUENCE OF GOOD COUNSELS, TO CAST OFF THEIR SAVAGE HABITS AND BECOME AN INTERESTING, CIVILIZED, AND CHRISTIAN COMMUNITY. WHAT GOOD MAN WOULD PREFER A COUNTRY COVERED WITH FORESTS AND RANGED BY A FEW THOUSAND SAVAGES TO OUR EXTENSIVE REPUBLIC, STUDDED WITH CITIES, TOWNS, AND PROSPEROUS FARMS EMBELLISHED WITH ALL THE IMPROVEMENTS WHICH ART CAN DEVISE OR INDUSTRY EXECUTE, OCCUPIED BY MORE THAN 12,000,000 HAPPY PEOPLE, AND FILLED WITH ALL THE BLESSINGS OF LIBERTY, CIVILIZATION AND RELIGION? THE PRESENT POLICY OF THE GOVERNMENT IS BUT A CONTINUATION OF THE SAME PROGRESSIVE CHANGE BY A MILDER PROCESS. THE TRIBES WHICH OCCUPIED THE COUNTRIES NOW CONSTITUTING THE EASTERN STATES WERE ANNIHILATED OR HAVE MELTED AWAY TO MAKE ROOM FOR THE WHITES. THE WAVES OF POPULATION AND CIVILIZATION ARE ROLLING TO THE WESTWARD, AND WE NOW PROPOSE TO ACQUIRE THE COUNTRIES OCCUPIED BY THE RED MEN OF THE SOUTH AND WEST BY A FAIR EXCHANGE, AND, AT THE EXPENSE OF THE UNITED STATES, TO SEND THEM TO LAND WHERE THEIR EXISTENCE MAY BE PROLONGED AND PERHAPS MADE PERPETUAL….RIGHTLY CONSIDERED, THE POLICY OF THE GENERAL GOVERNMENT TOWARD THE RED MAN IS NOT ONLY LIBERAL, BUT GENEROUS. HE IS UNWILLING TO SUBMIT TO THE LAWS OF THE STATES AND MINGLE WITH THEIR POPULATION. TO SAVE HIM FROM THIS ALTERNATIVE, OR PERHAPS UTTER ANNIHILATION, THE GENERAL GOVERNMENT KINDLY OFFERS HIM A NEW HOME, AND PROPOSES TO PAY THE WHOLE EXPENSE OF HIS REMOVAL SETTLEMENT. IN INSISTING UPON THE REMOVAL OF THE INDIAN, PRESIDENT JACKSON BELIEVED THAT IT WAS THE ONLY COURSE OF ACTION BY THE GOVERNMENT IF THE INDIAN WAS TO BE SPARED CERTAIN ANNIHILATION. NOT THAT HE WAS MOTIVATED PRINCIPALLY BY HIS CONCERN FOR THE SAFETY OF NATIVE AMERICANS. HIS MAIN CONCERN WAS THE SAFETY OF THE UNITED STATES, AND HE FIRMLY BELIEVED THAT THE INDIANS CONSTITUTED A DANGER AND THREAT TO THAT SAFETY. BUT HE WAS ALSO CONVINCED THAT IF INDIAN LIFE AND CULTURE WERE TO BE PRESERVED THEN THEY MUST REMOVE THEMSELVES FROM THE PRESENCE OF WHITE SOCIETY. Comparing Opinions on the Indian Resettlement Act of 1830 President Jackson—supporter of the act Senator Theodore Frelinghuysen (NJ)— opposed to the act “A portion…of the Southern tribes, having mingled much with the whites and made some progress in the arts of civilized life, have lately attempted to erect an independent government within the limits of Georgia and Alabama. These states, claiming to be the only sovereigns within their territories, extended their laws over the Indians, which induced the latter to call upon the United States for protection….I informed the Indians inhabiting parts of Georgia and Alabama that their attempt to establish an independent government would not be countenanced [approved] by the Executive of the United States, and advised them to emigrate beyond the Mississippi or submit to the laws of those states….I suggest…the propriety of setting apart an ample district west of the Mississippi, and without the limit of any State or Territory now formed, to be guaranteed to the Indian tribes as long as they shall occupy it, each tribe having distinct control over the portion designated for its use….This emigration should be voluntary….” “…Our ancestors found [the Indians] far removed from the commotions of Europe, exercising all the rights, and enjoying all the privileges, of free and independent sovereigns of this new world. They were not a wild and lawless horde of [bandits], but lived under the restraints of government….How is it possible that even a shadow of claim to soil, or jurisdiction, can be derived, by forming a collateral issue between the State of Georgia and the [federal] Government? [Georgia’s] complaint is made against the United States, for encroachments on her sovereignty….The Cherokees…hold [the land] by better title than either Georgia or the Union….True,…[the Indians] have made treaties with both, but not to acquire title or jurisdiction; these they had before….They [made treaties] to secure protection and guarantee for subsisting powers and privileges….” The Removal Act caused a storm of national controversy: the Indians had many champions among white Americans—traders, missionaries, even planters and politicians who applauded their efforts to assimilate. Nonetheless, the pressure(s) for removal had been building momentum for decades, focused especially on individual state governments. The case of the Cherokees The Cherokees Took the new ideas of republican government and blended them with their own tradition of tribal councils. Progressive Cherokee leaders attempted to construct a model society. The new Cherokee capital in GA, New Echota, established a 32member legislature, wrote a Constitution in 1827 similar to the U.S. Constitution, framed a judicial system, and published a newspaper (The Cherokee Pheonix). Propelled by the popularity of The Cherokee Phoenix, the literacy rate among their people was higher than that in surrounding American communities; The Cherokee Phoenix enjoyed a readership well beyond the tribal homelands. The Cherokees also established their own schools, owned slaves, and spoke a highly developed language (thanks to the genius of Sequoyah). “Where now are our grandfathers, the Delawares? We had hoped the white man would not be willing to travel beyond the mountains; now that hope is gone. They have passed the Mountains, and have settled on Cherokee lands….The remnant of the Ani-Yunwiya, the Real People, once so proud and formidable, will be obliged to seek refuge in some distant wilderness.” -Dragging Canoe Cherokee, 1768 He was an illiterate Arkansas Cherokee who spoke no English and knew nothing of writing except that it existed and the “talking leaves” gave whites who could read them man advantages. In English he was called George Guess or Guest; his Cherokee name was Sequoyah. His leg, withered since birth, consigned him to a reflective life. He became a fine silversmith and had a gift for drawing. About 1809, after an argument with friends on the nature of writing, Sequoyah began from curiosity to devise signs for words. It became an obsession. He neglected his farm and his family; he ignored those who laughed at him; he kept going when his wife and neighbors threw his early work into the fire. In 12 years he trod much of the ground covered by entire civilizations over centuries. At length he discovered that by breaking words into syllables, every sound in the Cherokee language could be represented by 86 characters. These were initially of his own design; later he took letters from the Roman and Greek alphabets to allow easy use by a printing press. The result was the first full writing system ever devised by a native North American. It proved easy to learn; most Cherokees mastered it in days, and it was soon adapted for use in other native languages. At one stroke he had broken the monopoly of letters enjoyed by whites and a select few Indians. In 1826 one of the latter, a brilliant young Cherokee named Elias Boudinot, began raising funds for a printing press with Sequoyan type. He got it, and in 1828 Boudinot began publishing his groundbreaking weekly, The Cherokee Phoenix, filling it with incisive articles and editorials—many of which were reprinted by sympathetic papers across the country. For the first time, a native voice reached a wide audience through the printed page. Sequoyah When Harriet Ruggles Gold, the daughter of Protestant parents from Cornwall, Connecticut, announced her intention to marry Elias Boudinot (a Cherokee student at the Foreign Mission School in Cornwall), a public outcry ensued and reaction was swift. The girls’ choir at the Golds’ church wore black armbands on their white robes in protest. Harriet’s family received hatfilled letters from neighbors. Officials of the mission school circulated a notice condemning “this evil.” The night before the ceremony, in March 1826, Harriet, her mother, and Elias were burned in effigy on the village green as a mob voiced its disapproval. Harriet, however, voiced no regrets at her decision: “The place of my birth is dear to me, but I love this people and with them I wish to live and die.” Cherokee Indian cases (1830s) Cherokee Nation versus Georgia The issue of Indian Removal came to a head in the landmark legal confrontation: Cherokee Nation vs. Georgia (1831) when the Cherokees brought suit in court against the State of Georgia for its attempt(s) to impose its laws over the Cherokee Nation. The background: In 1828 the GA state legislature passed a bill denying Indians the right to testify against whites in court (the Cherokees realized this measure would effectively deny them all legal protection and allow whites to seize Indian lands at will). By the time the case Cherokee Nation versus Georgia reached the Supreme Court, the Removal Act of 1830 had been passed, so the Cherokee asked the court for a ruling on its legality as well. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 passed by one vote . The act authorized the President to give the Five Civilized Tribes land in Indian Territory, later named Oklahoma, in exchange for the Southeastern lands they now occupied (the carrot). The stick was a provision that the new law could be enforced, if necessary, with military action. The Cherokees were led in their battle against removal by their principal chief, John Ross (born in 1790 to a Cherokee-Scotch mother and a Scottish father), the de facto head of government at New Echota (the Cherokee capital). Ross was educated in white schools—nonetheless, he was adamantly opposed to Jackson’s removal plan. Ross asserted that the Cherokee were a sovereign nation whose territory the federal and state governments must respect. Among the white prominent politicians Ross gained the support of were Senators Henry Clay and Daniel Webster. Still, Ross was not able to win over all his own people. Among those who disagreed with Ross was a Cherokee Council speaker called The Ridge (aka Major Ridge), who believed it was in the tribe’s best interest to negotiate with Washington—that is, to make the best deal possible and move West. It is worth noting that Ridge also wanted to replace Ross as the tribe’s principal chief. Major Ridge was supported by his son, John, as well as his cousin, Elias Boudinot (editor of The Cherokee Phoenix), and Boudinot’s brother, Stand Watie (collectively, they comprised what is known as “the Ridge Faction”). Unfortunately, only a few hundred others within the tribe favored accommodation (nevertheless, internal divisions gave single-minded white expansionists a valuable opening to exploit). John Marshall (Cherokee Nation v. Georgia) Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that Indian tribes were “domestic dependent nations” (i.e. wards of the federal government) and, as such, had no right to file suit in court. In his majority opinion, Chief Justice John Marshall reasoned that Indians were not subject to State law; nor were they independent. Rather, they were wards of the federal government (i.e. “domestic dependent nations in a state of pupilage.”) “John Marshall” by Henry Inman, 1832 Indian reaction(s) to removal: IN CONSEQUENCE OF THE SUPREME COURT RULING, CHEROKEES DID NOT SUBMIT TO GEORGIA LAW. MEANWHILE, THE STATE OF GEORGIA REFUSED TO RECOGNIZE THE COURT RULING, OPTING INSTEAD TO ENACT A STATE LAW IN DECEMBER 1830 PROHIBITING WHITE MEN FROM ENTERING INDIAN TERRITORY AFTER MARCH 1, 1831. RESULT: APPROXIMATELY A DOZEN MISSIONARIES WERE ARRESTED FOR VIOLATING THIS LAW (ALL BUT SAMUEL A. WORCESTER AND DR. ELIZUR BUTLER WERE PARDONED ON CONDITION THEY STAYED OUT OF INDIAN TERRITORY— WORCESTER AND BUTLER REFUSED THE CONDITION). WORCESTER AND BUTLER SUED FOR THEIR FREEDOM IN WORCESTER V. GEORGIA THE U.S. SUPREME COURT RULED AGAINST THE STATE OF GEORGIA AND REMANDED THE CASE BACK TO THE STATE SUPERIOR COURT OF GEORGIA WITH INSTRUCTIONS TO RELEASE WORCESTER AND BUTLER. THEN, IN A SECOND CASE (WORCESTER V. GEORGIA), THE COURT HELD FOR THE CHEROKEE, DECLARING THEM TO BE “A DISTINCT COMMUNITY, OCCUPYING ITS TERRITORY” WHICH THE PEOPLE OF GEORGIA HAD NO RIGHT TO ENTER WITHOUT CHEROKEE CONSENT. THE CONFLICT WAS RESOLVED WHEN JACKSON PRESSURED THE GOVERNOR OF GEORGIA TO PARDON THEM (THE TWO WERE RELEASED ON JANUARY 14, 1833) WHILE THE CHEROKEES WERE URGED BY THEIR FRIENDS IN CONGRESS TO REMOVE. Indian reaction(s) to removal contd. THE PRINCIPAL CHIEF OF THE CHEROKEE NATION, JOHN ROSS, WHO WAS ACTUALLY A SCOT WITH ONLY ONE-EIGHTH CHEROKEE BLOOD IN HIS VEINS, HAD ACTIVELY AND PERSISTENTLY THWARTED JACKSON’S DETERMINATION TO REMOVE HIS TRIBE BEYOND THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER. ROSS HOPED TO FORESTALL JACKSON (WHOM THE CHEROKEES REFERRED TO AS “GREAT FATHER”) FROM DISPATCHING THE REVEREND JOHN F. SCHERMERHORN TO THE CHEROKEE NATION TO WORK OUT A TREATY WITH THE “RIDGE FACTION” WHEN HE MET WITH THE PRESIDENT ON FEBRUARY 5, 1834. JACKSON PREFERRED TO WORK WITH THE RIDGE FACTION BECAUSE THEY UNDERSTOOD HIS DETERMINATION TO EXPEL THE CHEROKEES FROM THEIR EASTERN LANDS. AT LENGTH, WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF THE RIDGE TREATY PARTY, THE REVEREND SCHERMERHORN NEGOTIATED THE TREATY OF NEW ECHOTA—BY WHICH THE CHEROKEES CEDED TO THE UNITED STATES ALL THEIR LANDS EAST OF THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER IN EXCHANGE FOR $4.5 MILLION AND AN EQUIVALENT AMOUNT OF LAND IN THE INDIAN TERRITORY. THE TREATY OF NEW ECHOTA WAS THEN APPROVED BY THE CHEROKEE NATION (THROUGH FRAUD AND CHICANERY) BY THE INCREDIBLY SMALL VOTE OF 79-7. WHEREAS THE U.S. CONGRESS ACCEPTED THIS FRAUDULENT VOTE IN RATIFYING THE TREATY, ITS MEMBERS IGNORED THE PETITIONS IT RECEIVED BY OVER 14,000 CHEROKEES PROTESTING THE TREATY AFTER THE FACT. Indian reaction(s) to removal UPON SIGNING AWAY THE REMAINING CHEROKEE LANDS FOR TERRITORY WEST OF THE MISSISSIPPI AT NEW ECHOTA, MAJOR RIDGE RECALLED A CHEROKEE LAW OF 1829 THAT DECREED DEATH TO ANYONE SELLING LAND WITHOUT THE CONSENT OF ALL CHEROKEE PEOPLE. RIDGE GRIMLY REMARKED AT THE SIGNING CEREMONY: “WITH THIS TREATY, I SIGN MY DEATH WARRANT.” (HE WAS RIGHT—FOUR YEARS LATER RIDGE, HIS SON, AND ELIAS BOUDINOT WERE PUT TO DEATH FOR THEIR ACTIONS). ON JUNE 22, 1839, MAJOR RIDGE, HIS SON JOHN, AND ELIAS BOUDINOT WERE STABBED TO DEATH BY UNKNOWN ASSAILANTS, THEIR PUNISHMENT FOR SIGNING THE INFAMOUS 1835 TREATY OF NEW ECHOTA. AMNESTY WAS SUBSEQUENTLY OFFERED TO OTHERS WHO SIGNED AND THE UNIDENTIFIED EXECUTIONERS. TO FORCE COMPLIANCE WITH THE ILLEGAL TREATY OF NEW ECHOTA, THE U.S. GOVERNMENT SENT OVER 7,000 TROOPS INTO CHEROKEE COUNTRY. STATE MILITIAS SWELLED THE OCCUPATION ARMY TO MORE THAN 9,000 MEN. Removal “Removal” meant relocation beyond white settlements in Indian Territory (later Oklahoma) whereupon each tribe could function independently and without interference from the United States. The Cherokee called the tragedy of removal oosti ganuhnuh dunaclohiluh (“the trail where they cried”). The Trail of Tears by Robert Lindneux (1942) Tsali, Cherokee shaman: “The Great Spirit is displeased with you for accepting the ways of the white people. You can see for yourselves—your hunting is gone and you are planting the corn of the white men….You yourselves can see that the white people are entirely different beings from us; we are made from red clay.” While awaiting execution in 1838, Tsali, Cherokee Shaman is purported to have said: “I have a little boy….If he is not dead, tell him the last words of his father were that he must never go beyond the Father of Waters [the Mississippi River], but die in one’s native land and be buried by the margins of one’s native stream.” Among the Five Civilized Tribes, the Choctaw were the first to leave the soil of their ancestors, moving from Mississippi to eastern Oklahoma in large groups (1830-1846), some by boat up the Arkansas River and others overland. The Chickasaw began their migration from northern Alabama and Mississippi in 1837, after purchasing land in Oklahoma from the Choctaw (most went by boat). As soon as they arrived they were challenged by Plains Indians who claimed the newcomers had stolen land from local tribes (it would be years before they knew peace). Removal of the Creek began in 1836—still, Eneah Emathala (a Creek in his 80s who fought with the Red Sticks during the War of 1812) refused to move along with about 1,000 followers who took refuge in Alabama back country. Emathala was finally caught by General Winfield Scott and arrested/designated as a “hostile.” Emathala and the thousand men, women, and children who resisted removal with him were shackled hand and foot and marched 75 miles across Alabama to Montgomery. Its job not finished, the federal government then forcibly removed some 14,000 more Creeks (a process finally completed in December 1837). The Seminoles (who were the next to leave) did not go quietly or gently. When, in 1831, a drought struck Seminole crops in central Florida resulting in widespread famine by the Spring of 1832, U.S. agents swiftly moved in with offers of food and clothing in exchange for an agreement among the Seminoles to emigrate west to available land alongside the Creeks in Indian Territory. Dispirited by the drought, a small group of chiefs reluctantly signed two treaties agreeing to removal of the Seminole by 1835. But one Seminole refused to budge: Osceola. “You have guns, and so have we. You have powder and lead, and so have we. You have men and so have we. Your men will fight and so will ours, till the last drop of the Seminole’s blood has moistened the dust of his hunting ground.” Osceola, Seminole, 1836 “They could not capture me except under a white flag. They cannot hold me except with a chain.” Osceola, Seminole, 1838 Portrait of Osceola by George Catlin (made during Osceola’s last weeks) When the army came after Osceola, he took his warriors into the Florida swamps. There they abandoned guns (to the contrary of the quote above) in favor of bows and arrows so that they could hunt without being detected. Seminole fighters attacked government forces when they least expected it, harassing and frustrating the troops with resourceful guerilla (hit and run) tactics. In the fall of 1837, General Thomas S. Jesup asked Osceola to meet him under a flag of truce. When the Seminole came to talk, Jesup arrested him and threw him into a federal prison in South Carolina where Osceola died three months later. This act of treachery only deepened Seminole resolve, and the conflict raged for another seven years, until at last in 1842 a series of treaties officially ended it. About 4,000 Seminole survivors were duly moved west to Indian Territory, where U.S. authorities, citing their Creek heritage, settled them in Creek lands— among people some Seminoles regarded as enemies. Before long, Creek slaveholders in Oklahoma charged that the Seminoles were luring Africans from Creek farms with promises of freedom. When news of this was received back East, some of the Seminoles still in Florida refused to move. Like Osceola’s warriors, they retreated into the Everglades and the Big Cypress Swamp and eluded the federal troops that came for them. Several thousand of their descendants live in Florida to this day, unmoved and immovable. 1957 oil painting by Pawnee artist Brummett Echohawk commemorating the trek to Oklahoma By 1850 the Five Civilized Tribes had been relocated on the distant soil of Oklahoma. Externally, much of the region in which they had been relocated was inhabited by bands of Plains Indians, fast-moving hunterwarriors to whom the Southeastern tribes were as alien and unwelcome as white farmers. In the North the Sac and Fox Indians had been resettled west of the Mississippi but decided to return to their homes in Illinois when they found more difficulties than they anticipated on the great plains. White settlers panicked when the Indians appeared and soon state and federal troops were called in to expel the invaders. Under the leadership of Chief Black Hawk the Indians resisted and fought bravely and well. But the Black Hawk War lasted only a few months and by 1832 the Indians had fled back across the Mississippi River and Chief Black Hawk was taken prisoner whereupon he was hauled before President Jackson in Baltimore and chastised prior to being paraded around like a trophy. Chief Black Hawk “My Father. My ears are open to your words. I am glad to hear them. I am glad to go back to my people. I want to see my family….I ought not to have taken up the tomahawk. But my people have suffered a great deal. When I get back, I will remember your words. I won’t go to war again. I will live in peace.” Chief Black Hawk Removal did not end with the Five Civilized Tribes. Northern tribes like the Sac and Fox Indians, were also expelled from “civilized society.” The Chicago Treaty of 1833 with the Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi tribes provided the United States with valuable land in Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Iowa. Some ninety odd treaties were signed during the Jackson adminstration, including those with the Miami, Wyandot, Saginaw, Kickapoo, Shawnee, Osage, Iowa, Delaware, and other tribes. By the close of Jackson’s term in office some 45,690 Indians had been removed west of the Mississippi. The United States acquired about 100 million acres of land for about $68 million and 32 million acres of western lands. The Creek moved in along the Arkansas and Canadian rivers, cleared the land, and planted crops. The Cherokee laid out a new capital, Tahlequah, and revived their constitution. John Ross won reelection as principal chief. A public school system was in operation by 1841. The Cherokee Advocate, first newspaper in Indian Territory, appeared in 1844 and was soon joined by publications from other tribes. The Choctaw and Chickasaw nations drew up constitutions of their own, modeled on U.S. political procedures. More schools were established, and missionary societies were invited to open churches. The Seminole at length were recognized as a tribe and in 1856 given territory separate from the Creeks. Nearly a century after Removal, the Green Corn Dance was still being performed not only by tribes in Oklahoma but by the Eastern Band Cherokee of North Carolina, descendants of those Cherokee who eluded white troops and found sanctuary deep in the Appalachians. Despite their recovery, their struggle was not done. Having overcome the trauma of being forcibly removed from the land of their ancestors and the internal divisions within the tribes removal aroused, the surviving Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole exiles began to re-create their communities with remarkable speed and get on with their lives. The theft of their lands in the Southeast did not rob the Five Tribes of their ambitions. They built substantial homes, reestablished their own institutions and laws, printed newspapers and books in their own languages, opened schools based on Christian principles they had embraced, and established themselves as successful farmers and ranchers. THE EVANGELICAL CHRISTIAN MOVEMENT (PREDOMINANTLY CONGREGATIONALISTS AND PRESBYTERIANS) OPPOSED REMOVAL ON MORAL AND HUMANITARIAN GROUNDS. FROM A LARGER VANTAGE POINT, EVANGELICAL CHRISTIANS WERE ALARMED BY THE EMERGING MATERIALISM AND VIOLENT NATURE OF THE NEW POLITICS AND THE MARKET ECONOMY—PARTICULARLY BECAUSE THEY SEEMED TO CONFLICT WITH OLD CHRISTIAN WAYS. EVANGELICAL CHRISTIANS WERE LONG-TIME SUPPORTERS OF EFFORTS TO CIVILIZE AND CHRISTIANIZE THE INDIANS. CONGREGATIONALISTS AND PRESBYTERIANS COMPRISED THE PRIMARY BASE OF THE AMERICAN BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS FOR FOREIGN MISSION BASED IN BOSTON. THIS ORGANIZATION LED THE EVANGELICAL CHRISTIAN FIGHT AGAINST REMOVAL (PARTICULARLY JACKSON’S PROGRAM). THIS ORGANIZATION DEVELOPED AN EXTENSIVE PROGRAM FOR CIVILIZING THE INDIANS. THE MOST EFFECTIVE SPOKESMAN (AND CORRESPONDING SECRETARY) OF THE AMERICAN BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS FOR FOREIGN MISSIONS) WAS JEREMIAH EVARTS (BELOW RIGHT). BEGINNING IN AUGUST 1829, EVARTS PUBLISHED A SERIES OF 24 ESSAYS OPPOSING REMOVAL IN THE DAILY NATIONAL INTELLIGENCER UNDER THE PSEUDONYM OF THE FORMER QUAKER “WILLIAM PENN”. INDIANS ALSO ENJOYED LONG-STANDING QUAKER SUPPORT. Why did Native Americans and Europeans react to one another as they did? IN LIGHT OF THE NEARLY INEXHAUSTIBLE LITANY OF INJUSTICES, ATROCITIES, AND PROVOCATIONS INFLICTED UPON THE AMERINDIANS, IT IS EASY TO DESPISE THE SO-CALLED PERPETRATORS WHILE CHEERING THOSE INDIANS WHO EXACTED RETRIBUTION ON CUSTER (LITTLE BIG HORN) AND OTHERS LIKE HIM AS A FORM OF CATHARSIS. YET, AS CONAWAY POINTS OUT, “TO HOLD THE PARTICIPANTS TO PRESENT STANDARDS, TO INSIST THAT INEQUITY IS THE ONLY THING OF INTEREST IN EVENTS OF SUCH PASSIONATE COMPLEXITY IS TO MISS THE POINT….” CONAWAY CONTINUES: “PEOPLE OFTEN DO NOT LIKE THOSE WHO ARE DIFFERENT FROM THEMSELVES. THIS IS LAMENTABLE AND CAN LEAD TO INJUSTICE AND ATROCITY….BUT LAMENTATION ALONE IS INSUFFICIENT TO THE CREATIVE TASK. IT CANNOT ADEQUATELY PRESENT THE SALIENT ASPIRATIONS OF CONFLICTING CULTURES THAT THE MAKERS OF 500 NATIONS CHOSE AS THEIR ORGANIZING PRINCIPLE.” 500 Nations VI: Removal of War and Exile in the East ACCORDING TO JAMES CONAWAY, THE “REAL SUBJECT OF 500 NATIONS IS THE [CENTURIES-LONG] CONFLICT BETWEEN INDIGENES AND INTRUDERS.”