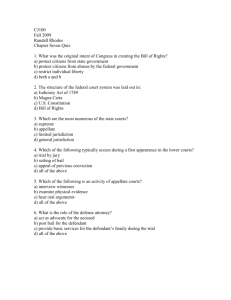

chapter_3_text-book

advertisement