Articles to read for 1/14/2014 Articlestragedy

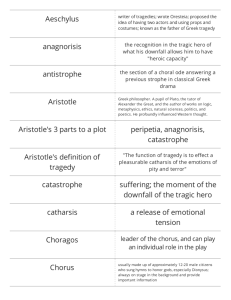

advertisement

Chorus - Jessamyn, Nick, Aredy and Amir Chorus For the modern reader the chorus is one of the more foreign elements of tragedy. The chorus is not one of the conventions of modern tragedy. We associate the chorus with such musical forms as opera, musical comedy and oratorio. But tragedy was not just straight drama. It was interspersed with songs sung both by actors and chorus and also with dancing by the chorus. The modern parallel for tragedy is actually opera (along with its descendant, musical comedy), which is a dramatic form containing song and dance. The chorus, unlike the actors, were nonprofessionals who had a talent for singing and dancing and were trained by the poet in preparation for the performance. The standard number of members of a chorus was twelve throughout most of Aeschylus's career, but was raised to fifteen by Sophocles. The chorus, like the actors, wore costumes and masks. The chorus was one of the most important components of the play. It narrates and reflects on the action. Without them, the audience would have no background information, and the play would be more confusing. The chorus entered from the two paradoi in three rows of five people. They formed little squares between them. The chorus was called by different names for each kind of play, reflecting a different emotion. In a tragedy, it was solemn and called "emmelia." In a comedy, it was funny and called "codrax." In a satyric drama, it was scoptic and called "sicinnis."The first function of a tragic chorus was to chant an entrance song called a parodosas they marched into the orchestra. The entrance song took its name from the two ramps (parodoi) on either side of the orchestra, which the chorus used as it made its way into the orchestra. Once the chorus had taken its position in the orchestra, its duties were twofold. It engaged in dialogue with characters through its leader, the Coryphaeus, who alone spoke the lines of dialogue assigned to the chorus. The tragic chorus's most important function was to sing and dance choral songs called stasima (singular = stasimon). The modern reader of Greek Tragedy, whether in English or even in the original Greek, finds it very difficult to appreciate the effect of these choral songs which are devoid of their music and dance. The chorus used the orchestra. They sang, or sometimes said, basic information. They were the narrators of the play. They also acted as crowds. They would dance in the orchestra to show what was going on in the scene. They were also like the extras in the play. If a large crowd was needed, they were the crowd. The leader of the chorus ("Coryphaios") was in the middle of the first row. Coryphaios was a professional dancer and singer. The rest of the chorus consisted of amateurs chosen by the poet and payed by the sponsor (choregos) The chorus was entering from the two " parodoi". His appearance depended on the play. The chorus, was considered to be the mouthpiece of society (in its humble form) and morality, and they were suffering along with the heroes. Its role (very important at first) was fading during the time. Makara, Ellie, Larissa and Ana – Sphinx website http://www.unmuseum.org/sphinx.htm Lila, Kira, Leo,Simon, Anasophia The Origins of Theater The roots of ancient Greek theater lie in the cult of Dionysus, the god of wine and fertility, one of the Olympian deities honored in the Greek world. In myth, Dionysus' followers were satyrs, drunken half-animal, half-human creatures, and maenads, or "mad women". In ancient Greek times, Dionysus' followers sometimes assumed these roles (pretended to be satyrs or maenads) in their religious rituals, resulting in much singing, drinking, and dancing in honor of their god. This celebration, which occurred in December in the countryside and March in the city, could not start until certain rituals had been completed. In Athens, for instance, a wooden statue of Dionysus would be taken from Eleutherai to the city. On the evening of its arrival, the statue would be moved to one of the god's sanctuaries where a bull would be killed in his honor. The performance of a dithyramb, a song dedicated to Dionysus, might have taken place at this time as well. Members of the Dionysiac cult always told of the myths centered around their god by singing and dancing out their stories together as a chorus. Always, that is, until one day ( about 2,500 years ago) in the sixth century BC, when a man named Thespis, a Dionysian priest, stepped out of the chorus and took on the role of an actor. Thespis acted out a Dionysiac myth through spoken dialogue rather than a song, creating Greek tragedy. He is considered to be the first actor and the first playwright. After this new form of performance had been introduced to the general public, it quickly gained popularity. Its popularity lead Pisistratus, an Athenian tyrant, to construct a theater, for the performance of tragedy, in Dionysus' honor. Under Pisistratus' rule, tragedy turned into a competition for the best play in 538 BC. Soon thereafter, these theatrical performances gained new importance and meaning, and in 534 BC the first festival of Dionysus was instituted. The first recorded victory at the Dionysian Festival occurred that same year when Thespis, also a playwright, won the event. The Dionysian festival represented not only an opportunity for the ancient Greeks to celebrate Dionysus, but it also provided yet another opportunity for them to participate in competition. Once tragedy had become an established art form, theater competition quickly expanded to include satyr plays and comedy. Tragedy appeared at the Dionysian Festival for the first time in 534 BC (as noted above), followed by the satyr play in approximately 500 BC, and comedy in 486 BC. Unfortunately, the only Greek plays to have survived date from 490 to 300 BC, a fairly short time period. The majority of tragic plays, we are unsure of who wrote certain ones, are said to have been written by Aeschylus (525-426 BC), Sophocles (496-406 BC), and Euripides (485-406 BC), while the comedies are attributed to Aristophanes (450-385 BC) and Menander (342-290 BC). Although most of their plays have been lost or destroyed, we have been left with a fairly good impression of their individual styles. Their writings have also provided us with valuable information concerning the performance and subject matter of Greek plays. Although we know that successful playwrights taking part in the competitive festivities of the City Dionysia were awarded a prize, we do not know what the prize amounted to. It is likely that the existence of a prize played only a small role in motivating the ancient Greek playwrights to participate in the competition, as evidence shows that the participants appear to have belonged to the class of Athenians who could support themselves without working, and whose extra time and funds allowed them to participate in public life. More likely, it was the combination of the ancient Greeks' competitive nature with their desire to honor their god, that drove them to participate year after year in the theatrical competitions of the festivals of Dionysus. Apollo is a many-talented Greek god of prophecy, music, intellectual pursuits, healing, plague, and sometimes, the sun. Writers often contrast the cerebral, beardless young Apollo with his half-brother, the hedonistic Dionysus, god of wine. Apollo versus Oedipus: divine versus human knowledge Apollo:the god who carries fire, light Gods and goddesses Greek religion was polytheistic; the Greeks worshipped many gods. The most powerful god was Zeus, the sky god, who was thought to have taken power when he overthrew his father Cronus, After Zeus came the other Olympian deities, including Zeus’ queen Hera, his brother Poseidon, and his children Athena, Ares, Artemis, and Apollo. There were also other gods, older deities from the region of Cronus who remained powerful and were often irrational. Among these are the Furies, dreadful goddesses who hunt down and drive mad humans who kill blood-relatives. The most important god for the Oedipus Rex is Apollo, whose oracle at Delphi gives the important prophecies to Oedipus and Creon 9laius was traveling to this oracle when he was killed). Apollo’s knowledge is absolute – if Apollo says something will happen, it will happen. His prophecies in this play, however are not warnings: he does not tell Laius not to have children, merely that his child will kill him. He does not tell Oedipus to kill his father, but that he will his father,. When Oedipus sends Creon to find out how to end the plague, Apollo tells them to drive the murderer of Laius out of Thebes, but this is not an instruction so much as a simple answer. Ray, Erin, Emery, Emelie Aristotle’s Poetics Definition of Tragedy – “Tragedy, then, is an imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude; in language embellished with each kind of artistic ornament, the several kinds being found in separate parts of the play’ in the form of action, not of narrative; with incidents arousing pity and fear, wherewith to accomplish its catharsis of such emotions…Every Tragedy, therefore must have six parts, which parts determine its quality – namely, Plot, Characters, Diction, Thought, Spectacle, Melody.” Tragedy is the ‘imitation of an action’ (mimesis) according to ‘the law of probability or necessity.’ Aristotle indicates that the medium of tragedy is drama, not narrative; tragedy SHOWS rather than TELLS. According to Aristotle, tragedy is higher and more philosophical than history because history simply relates what has happened while tragedy dramatizes what may happen, ‘what is possible according to the law of probability or necessity.’ History thus deals with the particular and tragedy with the universal. Events that have happened may be due to accident or coincidence; they may be particular to a specific situation and not be part of a clear cause and effect chain. Therefore, they have little relevance for others. Tragedy, however, is rooted in the fundamental order of the universe; it creates a cause-and-effect chain that clearly reveals what may happen at any time or place because that is the way the world operates. Tragedy, thererfore arouses, not only pity but also fear, because the audience can envision themselves within this cause and effect chain. Character has the second place in importance. In a perfect tragedy, character will support plot, i.e., personal motivations will be intricately connected parts of the cause and effect chain of actions producing pity and fear in the audience. The protagonist should be renowned and prosperous, so his change of fortune can be from good to bad. This change, ‘should come about as a result, not of vice, but of some great error or frailty in a character.’ Such a plot is most likely to generate pity and fear in the audience, for ‘pity is aroused by unmerited misfortune, fear by the misfortune of a man like ourselves.’ The term Aristotle uses here, hamartia, often translated ‘tragic flaw’ has been the subject of much debate. The meaning of the Greek word is closer to ‘mistake’ than to ‘flaw,’ and I believe it is best interpreted in the context of what Aristotle has to say about plot and ‘the law or probability or necessity.’ In the ideal tragedy, claims Aristotle, the protagonist will mistakenly bring about his own downfall – not because he is sinful or morally weak, but because he does not know enough. The role hamartia in tragedy comes not from its moral status but from the blindness, leading to results diametrically opposed to those that were intended (often termed tragic irony), and the anagnorisis is the gaining of the essential knowledge that was previously lacking. The end of a tragedy is a catharsis (purging, cleansing) of the tragic emotions of pity and fear. 1. The tragic hero is a character of noble stature and has greatness. This should be readily evident in the play. The character must occupy a ‘high’ status position but must ALSO embody nobility and virtue as part of his innate character. 2. Though the tragic hero is pre-eminently great, he is not perfect. Otherwise, the rest of us – mere mortals – would be unable to identify with the tragic hero. We should see in him or her someone who is essentially like us, although perhaps elevated to a higher position in society. 3. The hero’s downfall, therefore is partially his own fault, the result of free choice, not of accident or villainy or some overriding malignant fate. In fact, the tragedy is usually triggered by some error of judgment or some character flaw (known as hamartia). Often the character’s hamartia involves hubris (arrogant pride or over-confidence) 4. The hero’s misfortune is not wholly deserved. The punishment exceeds the crime. 5. The fall is not pure loss. There is some increase in awareness, some gain in self-knowledge, some discovery on the part of the tragic hero. 6. Though it arouses solemn emotion, tragedy does not leave its audience in a state of depression. Aristotle argues that one function of tragedy is to arouse the ‘unhealthy’ emotions of pity and fear and through a catharsis cleanse us of those emotions.