Note - Anne Sibert

advertisement

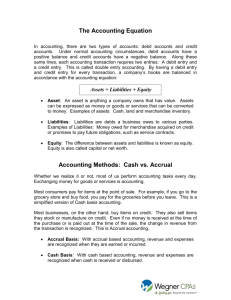

BSc Financial Economics: International Finance Lecture 1: Balance of Payments Accounting ANNE SIBERT1 Autumn 2013 I. INTRODUCTION A country’s balance of payments is a record of the transactions between its residents and the residents of the rest of the world. A fundamental principle of accounting is that when a transaction is recorded there are always two entries made. This is because a participant in a transaction receives something and gives up something in return. Thus, one of the entries records what was received and the other entry records what was given up. The monetary value of what was received equals the monetary value of what was given up. Records of transactions in the balance of payments are grouped into two main types. In the first group are entries recording the purchase and sale of goods and services. In the second group are entries recording the purchase and sale of financial assets. Equivalently, one might view the first group as entries that change a country’s net worth. The purchase of a good or services lowers its net worth; the sale of a good or service increases its net worth. The second group of entries than then be viewed as a record of how a country borrows from the rest of the world (or decreases its lending to it) to finance a fall in net worth or a record of how a country lends to the rest of the world (or decreases its borrowing from it) when it experiences an increase in its net wealth. Alternatively, when country A’s net worth falls, either its claims on the rest of the world go down or the rest of the world’s claims on it go up. When country A’s net worth rises, either its claims on the rest of the world go up or the rest of the world’s claims on it go down. To see how this works, consider some examples. Example 1. A resident of country A buys a computer from country B, paying with a cheque drawn on a bank in country A. In the above example, the resident of country A received a good and gave up a cheque in return. The purchase of the good lowered his net worth and, thus, the net worth of Country A. This part of the transaction – the purchase of the good – is recorded in the first group of transactions, the ones that record changes in the country’s net worth. The resident of Country B that sold the computer now has a cheque drawn on a bank in country A and, hence, a claim on that bank. Thus, country B now has an increased claim on Country A. This increase in the rest of the Professor Anne Sibert, Dept. of Economics, Mathematics and Statistics, Birkbeck, University of London, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HX, United Kingdom, a.sibert@bbk.ac.uk. Copyright © Anne Sibert 2013 1 1 world’s claims on country A is recorded in the second group of entries – the ones recording the purchase and sale of financial assets. Example 2. A resident of country A buys a bond issued by the government of country B from country B, paying for it with a cheque drawn on a bank in country B. This second example is a trade of one financial asset (a claim on the bank in country B) for another financial asset (a claim on the government of country B). This transaction has no effect on Country A’s net worth and both parts of the transaction are recorded in the second group of transactions. The payment with a cheque is a decrease in country A’s claims on country B; the purchase of the bond is an increase in country A’s claims on country B. Example 3. A resident of country A gives a gift to a resident of country B. This transaction seems to have only one part: the giving of the gift. However, the principles of accounting require that it be recorded twice. Thus, we think of the giver of the gift as receiving some intangible benefit with the same monetary value as the gift. Receiving this unspecified benefit raises country A’s net wealth. Thus, this part of the transaction, receiving an intangible benefit from giving a gift, is recorded in the first group of transactions. If the gift was a good or service, then country A has less of that good and service and its net worth declines. In this case the giving up of the good or service is recorded in the first group of transactions as well. If the gift was a financial asset, then the giving up of the financial asset is recorded in the second group of transactions. 2. DOUBLE-ENTRY BOOKKEEPING The notion that each transaction has two parts and is recorded twice is formalized in the notion of double-entry bookkeeping. I begin with some definitions. Definition 1. Assets are economic resources. They are what an entity owns. Definition 2. Liabilities are claims against assets. They are what an entity owes. A transaction must Increase one asset and decrease another asset or Increase one liability and decrease another liability or Increase both an asset and a liability or Decrease both an asset and a liability. From this is it seen that recording any transaction involves recording (i) either an increase in an asset or a decrease in a liability and (ii) recording either a 2 decrease in an asset or an increase in a liability. We thus have the following two definitions. Definition 3. Debit (abbreviated as dr) entries are entries recording an increase in an asset or a decrease in a liability. Definition 4. Credit (abbreviated as cr) entries are entries recording a decrease in an asset or an increase in a liability. Clearly, recording a transaction must then involve one debit entry and one credit entry. Entries are recorded into accounts in ledgers, which were once in bound volumes and are now typically collections of computer records. The accounts in the ledger are called T accounts to reflect what was once their physical appearance. This is shown in Figure 1, below. Figure 1. T Account Debit entries go on the left Name of the Account Credit entries go on the right To see how this works, we temporarily depart from balance of payments accounting and consider the accounting of George’s Shoe Store. George’s shoe store has three accounts: Inventory (the shoes), Cash and Accounts Payable (what George owes). Note that George’s three accounts fall into one of two types. Inventory and Cash are records of George’s assets; Accounts Payable is a record of George’s liabilities. As debit entries record increases in assets, increases in inventory and shoes are recorded on the left-hand side of their T accounts. As credit entries are increases in liabilities, increases in Accounts Payable are recorded on the right-hand side. We now consider three examples of transactions. Example 4. George sells shoes for 500 pounds and payment is in cash. George now has 500 pounds worth of shoes less than he did before. This is a decrease in an asset (Inventory), and hence is a credit entry. He should credit Inventory 500 pounds. George also has 500 pounds more cash than he did before. This is an increase in an asset (Cash), and hence is a debit entry. He should debit Cash 500 pounds. The credit entry for Inventory is entered on the right-hand side of the Inventory T account; the debit entry for Cash is entered on the left-hand side of the Cash T account. Inventory 500 (1) Cash 500(1) The parentheses with the number one inside indicate that this is transaction 1. 3 Example 5. George buys 700 pounds worth of shoes from the manufacturer; payment is due in 30 days. George now has 700 pounds more of shoes. This is an increase in an asset (Inventory) and, hence, a debit entry. He has 700 pounds more of debt (Accounts Payable). This is an increase in a liability and, hence, a credit entry. The debit entry for Inventory is entered on the left-hand side of the Inventory T account; the credit entry for Accounts Payable is entered on the right-hand side of the Accounts Payable T account. 700 (2) Inventory 500 (1) Accounts Payable 700 (2) Example 6 George pays the manufacturer 700 pounds cash. George now has 700 pounds less of cash. This decrease in an asset is a credit entry for the Cash account. He also has 700 pounds less of debt. This decrease in a liability is a debit entry for the Accounts Payable account. The credit entry for the Cash account is entered on the right-hand side of its T account; the debit entry for Accounts Payable is entered in the left-hand side of its T account. 500 (1) Cash 700 (3) Accounts Payable 700(3) 700 (2) We can now net George’s accounts: Inventory 700 (2) 500 (1) 200 Cash 500 (1) 700 (3) 200 Accounts Payable 700 (3) 700 (2) 0 The balances the for the three accounts can be found using the following convention: Credits are entered as positive numbers Debits are entered as negative numbers Thus, inventory with its net left-hand balance of 200 is, on net, debited by 200. Thus, it has a balance of – 200. Note that this is the case despite inventory increasing by 200. Cash, with its net left-hand balance of 200 is, on net, credited by 200. Thus, it has a balance of + 200. Note that this is the case despite cash falling by 200. Accounts Payable has a zero net credit balance, entered as + 0. 3. BALANCE-OF-PAYMENTS ACCOUNTING 4 Definition 5. A nation’s balance of payments is a record of transactions between that country and residents of the rest of the world. Note that from the above definition, balance-of-payments transactions are between residents, not citizens. Tourists, military and diplomatic personnel and temporary migrants are not considered to be residents. A permanent migrant is a resident, even if not a citizen. Foreign subsidiaries are residents of the country in which they are located. Thus, the sales of a subsidiary of a foreign company located in a host country are considered exports of the host country, and not of the country in which the parent company is located. If a subsidiary of a Korean automobile plant that is located in the United Kingdom sells automobiles to residents of Korea, this is a UK export and a Korean import. One can think of the balance of payments as a record of the components of the budget constraint for the country as a whole. A country’s budget constraint is shown in the box in Figure 2, below. All entries are total monetary values. Figure 2. A Country’s Budget Constraint Net exports of goods and services + net investment income received from foreigners + net unilateral transfers (that is, gifts) received from foreigners = change in home claims on foreigners – change in foreign claims on the home country Note that the above equation is inadequate in one way. There should be a term on the left-hand side of the equation that captures a country’s net capital gains. It is a shortcoming of balance of payments accounting that capital gains and losses are not accounted for. 3.1 Current Account In the Introduction, it was noted that transactions can be grouped into two main types. The first group of transactions is called the current account. These are the transactions on the left-hand-side of the equation in Figure 2. These transactions change the net worth of the country. Definition 6. A nation’s current account is a record of residents’ trade in goods and services with the rest of the world. Alternatively, it is a record of transactions that affect a country’s net wealth. The current account has four main subaccounts: Merchandise Trade: This is a record of trade in physical (or tangible or visible) goods, such as automobiles and computers. It is usually 5 broken down into two sub-accounts: merchandise exports (sales of goods) and merchandise imports (purchases of goods). Services: This is a record of trade in non-physical (or intangible or invisible) goods and services, such as insurance, shipping, consulting, fees and patents from copyrights and tourism. Income: This is a record of trade in the services of capital and labour. It includes interest income and dividends. Current Transfers: This is a record of one-sided transactions such as government grants, pension payments, private transfers (gifts), worker remittances from abroad and direct foreign aid. The balance of trade used to be the same thing as the merchandise trade balance. Now it is usually the sum of the balances of merchandise trade and services. There is one important type of gift that is not part of the current transfers account and that is debt forgiveness. Significant amounts of debt forgiveness for some highly indebted countries was distorting their balance of payments data, so a new account was introduced called the capital account. The capital account records gifts with long-term implications, such as debt forgiveness. It also includes such things as the change in financial asset ownership brought about by migration and inheritance. Thus, the transactions affecting the left-hand side of a country’s budget constraint (the change in a country’s net worth) in Figure 2 are included in both the current account and the capital account, with gifts with short-term implications included in the current transfers part of the current account and gifts with longterm implications (mainly debt forgiveness) included in the separate capital account. Definition 7. The capital account includes (mainly) debt forgiveness, assets accompanying migrants as they enter and leave the country and inheritance taxes. The name of given to the account with the long-term transfers is unfortunate. It used to be that the transactions on the right-hand side of the budget constraint in Figure 2 were grouped into two groups: changes in financial assets held by the central bank and all other changes in financial assets. This second group of transactions was called the capital account. Now, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the United Nations System of National Accounts (SNA) call the second group of transactions the financial account (discussed in the next subsection). Therefore, so di I, and so do many other academics and commentators. However, older textbooks refer to what is in more modern terminology is known as the financial account as the capital account. And, some current commentators and academics cling to this older terminology as well. 6 What does a positive or negative balance on the current account mean? We have that an export is a decrease in an asset as the country has sold, and thus no longer has, a good that it used to have. So, an export is a credit entry and is thus entered as a positive number. Similarly, an import is an increase in an asset as the country has bought a good that it did not used to have. So, an import is a debit entry and is entered as a negative number. Hence, a country that sells more goods and services than it buys has a current account surplus (that is, it has a positive balance); a country that buys more goods and services than it sells has a current account deficit (that is, it has a negative balance. A current account surplus is associated with an increase in net worth; a current account deficit is associated with a decrease in net worth. The entries associated with the left-hand side of the budget constraint in Figure 2 can now be grouped into the following balance of payments accounts: Current Account Merchandise Trade Exports Imports Services Income Current Transfers Capital Account 3.2 Financial Account Transactions affecting the right-hand side of the budget constraint in Figure 2 are grouped into the financial account. Definition 8. The financial account is a record of capital flows between residents of a country and residents of the rest of the world. The presentation of the financial account (once called the capital account) can differ from country to country and over time. One way to break down the financial account into subaccounts is to differentiate between types of transactions. There are two main types of capital flows: Direct investment: when residents of a country acquire shares in a foreign firm with the intent of exercising management control. For operational purposes this is usually defined as purchasing at least ten percent of the stock. Portfolio investment: management control. investment 7 without the intent of exercising Another way to differentiate between capital flows is as is done in the right-hand side of the equation in Figure 2: Home claims on foreigners Foreign claims on the home country A third way to break down capital flows is by the type of entity doing them: Private financial flows Commercial bank financial flows Central bank financial flows A fourth way, that countries used to break down financial flows was between long- and short-term capital flows. However secondary markets exist for many longterm financial assets and so this breakdown has become increasingly meaningless and is no longer used. Most countries use some combination of the above groupings. Perhaps the most common presentation of the financial account for advanced economies is something similar to: Direct Investment Home Claims on Foreigners (this does not include direct investment or changes in assets held by the central bank) Foreign Claims on the Home Country (this does not include direct investment) Official Reserves Definition 9. Changes in Official Reserves are changes in the financial assets held by the central bank. For most countries the main component of Official Reserves is the central bank’s holdings of foreign currencies: its foreign exchange reserves. Other components include the central bank’s holdings of gold, its Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) and its reserve position in the IMF. SDRs are a type of reserve asset that takes its value from that of a basket (or combination) of currencies. It was introduced in 1969 as an alternative reserve asset to the dollar, but is relatively unimportant, accounting for perhaps about four percent of the world’s official reserves in 2011. The official reserve position in the IMF is the amount of the country’s IMF quota (usually about one fourth) that a country can access at any time. What does the balance on the financial account mean? Capital inflows occur when the country borrows from the rest of the world or reduces its lending to the 8 rest of the world. Thus, a capital inflow occurs when foreign residents buy a home financial asset or when home residents sell a foreign financial asset. The former is an increase in a liability; the latter is a decrease in an asset. So, a capital inflow is a credit entry. Similarly, a capital outflow occurs when home residents buy a foreign financial asset or when foreign residents sell home financial assets. The former is an increase in an asset; the latter is a decrease in a liability. So a capital outflow is a debit entry. Thus, since credit entries are positive and debit entries are negative, a country with a financial account surplus had net capital inflows; a country with a financial account deficit had net capital outflows. In terms of the right-hand side of the budget constraint in Figure 2, the balance on the Financial Account is minus one times the right-hand side, which measures net capital outflows. To summarise, a typical presentation of the right-hand side of the budget constraint in Figure 2 for advanced economies is Financial Account Direct Investment Home Claims on Foreigners Foreign Claims on the Home Country Official Reserves The main reason for changes in the official reserves of central banks is changes in foreign exchange reserves brought about by central bank intervention in the foreign exchange market. The reason that central banks intervene in the foreign exchange market is to influence the value of their exchange rate. Thus, countries with fixed exchange rates tend to intervene regularly and can have large changes in their reserves over time; countries with floating exchange rates may intervene little. Thus, the Official Reserves account is important for countries with fixed exchange rates. It can indicate the extent to which their currency is undervalued or overvalued. For countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom and members of the Euro Area it is not a particularly important account. So, it makes sense for countries with floating exchange rates to consider Official Reserves as a subaccount of the Financial Account. It also makes sense for some countries with a floating exchange rate to list it separately, so that the right-hand side of the equation in Figure 2 is the sum of the Financial Account and the Official Reserve account. How should we interpret the balance on the Official Reserve account? If the central bank sells foreign reserves, this is a decrease in an asset and a credit entry. If it buys foreign reserves, this is an increase in an asset and a debit entry. Thus, somewhat counter-intuitively, a positive balance on the Official Reserve account corresponds to a fall in reserves; a negative balance to an increase in reserves. 3.3 Balance-of-Payments Equilibrium As each transaction is entered twice, once as a debit and once as a credit and as debits are minus numbers and credits are positive numbers, the sum of all entries in the balance of payments should equal zero. That is for countries that include the 9 Official Reserve account in the Financial Account, the sum of the Current Account, the Capital Account and the Financial Account should equal zero. For countries that do not include the Official Reserve account in the Financial Account, the sum of the Current Account, the Capital Account, the Financial Account and the Official Reserve account should equal zero. In this case the term balance of payments sometimes has another definition as the sum of the current account, the capital account and the financial account. Or, equivalently it is defined as minus one times the Official Reserve account balance. Or, equivalently to that, it is equal to the change in central bank reserves. Definition 10. The balance of payments is the change in central bank reserves. In practice the accounts to not sum to zero. Thus, we have the following definition. Definition 11. The statistical discrepancy (or errors and omissions) is the amount needed to make the balance of payments accounts sum to zero. The accounts sum to zero in theory, but not in practice, because the data for the two sides of the transaction may be collected by different agencies and it is not always terribly accurate. Data on merchandise trade comes from customs declarations and is typically the most accurate part of the accounts. Trade in services is typically estimated by various sampling techniques and errors can be substantial. Reporting of capital flows and investment income is highly imperfect, to a great extent because of tax evasion. 4. EXAMPLES OF HOW TRANSACTIONS ARE RECORDED This section provides some examples of how transactions are recorded. Suppose that the United Kingdom has the following accounts: merchandise exports, merchandise imports, services, income, current transfers, capital account, direct investment, UK claims on foreigners, foreign claims on the UK, official reserves. I. II. III. IV. V. VI. A UK firm buys 10 million pounds of computers from a Japanese firm, paying with cheques drawn on UK banks. A UK firm sells 7 million pounds of sweaters to residents of the United States. Payment is in the form of cheques drawn on US banks. A UK firm pays Spanish investors 1 million pounds in interest income, using cheques drawn on UK banks. UK investors buy a company in Italy, paying 2 million pounds with cheques drawn on UK banks. Residents of the United Kingdom send food worth 3 million pounds to a small country hit by a hurricane. The Bank of England intervenes in the foreign exchange market buying foreign reserves worth 1 million in exchange for claims on the Bank of England. 10 Before proceeding, note cheques drawn on UK banks are claims on the UK and that cheques drawn on foreign banks are claims on foreigner. Thus, we have the following outcomes that depend on whether a UK resident is paying or is being paid and whether the cheque involved in drawn a UK or on a foreign bank: Pays with a cheque drawn on Increase in a liability: credit Foreign Claims on the UK Decrease in an asset: credit UK Claims on Foreigners a UK bank: a foreign bank: Is paid with a cheque drawn on Decrease in a liability: debit Foreign Claims on the UK Increase in an asset: Debit UK Claims on Foreigners So the transactions are recorded (in millions) as follows: I. Debit Merchandise Imports 10 II. III. UK Claims on Foreigners 7 Income 1 IV. Direct Investment 2 V. VI. Current Transfers 3 Official Reserves 1 Credit Foreign Claims on the UK 10 Merchandise eEports 7 Foreign Claims on the UK 1 Foreign Claims on the UK 2 Merchandise Exports 3 Foreign Claims on the UK 1 Thus, on the basis of the above transactions: Current Account -4 Merchandise Trade 0 Merchandise Exports 10 Merchandise Imports -10 Services 0 Income -1 Current Transfers -3 11 Capital Account Financial Account 4 Direct Investment -2 UK claims on Foreigners -7 Foreign claims on the UK 14 Official Reserves -1 The UK had a current account deficit of 4 million and a financial account deficit of 4 million. There were net capital inflows of 4 million. The balance of payments surplus was 1 million as official reserves increased by 1 million. 5. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE BALANCE OF PAYMENTS ACCOUNTS AND THE NATIONAL INCOME ACCOUNTS Ignoring the capital account, we have that the left-hand side of the equation in Figure 2 is the current account. Thus, we have that The current account = change in home holdings of foreign assets – change in foreign holdings of home assets = change in home holdings of foreign assets + change in home holdings of home assets – change in home holdings of home assets – change in foreign holdings of home assets = home saving – home investment. An alternative way to find this is to start with the national accounting identity: Y = CT + IT + current account, where Y is home output or income, CT is total private and government home consumption, IT is total private and government home investment and G. Then Y CT is home saving. So, again we have that the current account is home saving minus home investment. In trying to think about why a country is running a large current account surplus or deficit, it is usually most useful to explain why investment is much smaller or larger than saving. Another way to write the national accounting identity is 12 Y = C + I + G + current account, where C is private home consumption, I is private home investment and G is government spending. Then, we have Y – T = C + I + G – T + current account, where T is tax revenue. The left-hand side, Y – T, is disposable income and Y – T – C is private saving. The government budget deficit is G – T; hence we have that private saving – private investment = government budget deficit + current account This has lead to the Twin Deficits Hypothesis that there is a link between the high government budget deficits and current account deficits. But, there is little evidence of this. 13