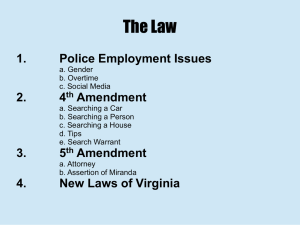

Criminal Procedure – Goldman (2010)

advertisement