Self-Compassion and Psychological Flexibility

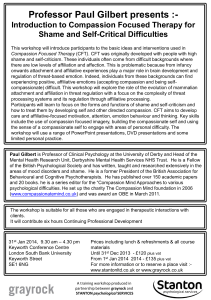

advertisement

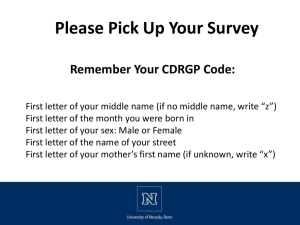

Self-Compassion From an ACT Perspective: An Intellectual and Experiential Exploration Dennis Tirch PhD & Jason Luoma PhD www.mindfulcompassion.com http://www.portlandpsychotherapyclinic.com Rate how often you behave in the ways below, using the following scale: Almost never 1 Almost always 2 3 4 5 _____1. When I fail at something important to me I become consumed by feelings of inadequacy. _____2. I try to be understanding and patient towards those aspects of my personality I don’t like. _____3. When something painful happens I try to take a balanced view of the situation. _____4. When I’m feeling down, I tend to feel like most other people are probably happier than I am. _____5. I try to see my failings as part of the human condition. _____6. When I’m going through a very hard time, I give myself the caring and tenderness I need. _____7. When something upsets me I try to keep my emotions in balance. _____8. When I fail at something that’s important to me, I tend to feel alone in my failure _____9. When I’m feeling down I tend to obsess and fixate on everything that’s wrong. _____10. When I feel inadequate in some way, I try to remind myself that feelings of inadequacy are shared by most people. _____11. I’m disapproving and judgmental about my own flaws and inadequacies. _____12. I’m intolerant and impatient towards those aspects of my personality I don’t like. 2 Compassion Solutions Ancient wisdom Compassion transforms the mind. (Buddhism) Evolution Evolution has made our brains highly sensitive to internal and external kindness Neuroscience Specific brain areas are focused on detecting and responding to kindness and compassion ACT Compassion is a value inherent in psychological flexibility model – Self-compassion related to flexible perspective taking Compassion definitions Compassion can be defined in many ways: “As a sensitivity to the suffering of self and others with a deep commitment to try to relieve it” Dalai Lama Eight fold path - represents a multi-modal approach for training one’s mind Compassion Definitions Neff (2003b) has operationalized selfcompassion as consisting of three main elements: 1. Self-kindness vs harsh criticism and selfjudgment 2. A sense of common humanity vs seeing self as separate and isolated 3. Mindfulness vs overidentification Self-Compassion and Psychological Flexibility These components combine and mutually interact to create a self-compassionate frame of mind. Self-compassion is relevant when considering personal inadequacies, mistakes, and failures, as well as when confronting painful life situations that are outside of our control. Self-Compassion Data Higher levels of reported self-compassion are correlated with: • Lower levels of depression and anxiety (Neff, 2003; Neff, Hseih, & Dejitthirat, 2005; Neff, Rude, & Kirkpatrick, 2007) • life satisfaction, feelings of social connectedness (Neff, Kirkpatrick, & Rude, 2007) • personal initiative and positive affect (Neff, Rude, et al., 2007) Compassion Training Data Practice in imagining compassion for others • produces changes in frontal cortex and immune system (Lutz et al, 2009) Loving kindness meditation • increases positive emotions, mindfulness, feelings of purpose in life and social support and decreases illness symptoms (Frederickson et al, 2008, JPSP) Compassion meditation (6 weeks) • improves immune function, and neuroendocrine and behavioral responses to stress (Pace, 2008, PNE) Compassion training • reduces shame and self-criticism in chronic depressed patients (Gilbert & Proctor, 2006, CPP) Self-Compassion from a CBS perspective Dahl, Plumb, Stewart and Lundgren, (2009) • Self-Compassion involves: – willingly experiencing difficult emotions; – mindfully observing our self-evaluative, distressing and shaming thoughts without allowing them to dominate our behavior or our states of mind – engaging more fully in our life’s pursuits with selfkindness and self-validation – flexibly shifting our perspective towards a broader, transcendent sense of self (Hayes, 2008a). Self-Compassion and Psychological Flexibility • Our learned capacity for flexible perspective taking is involved in our experience of empathy (Vilardaga, 2009), as well as our related experience of compassion. • In order to understand self-compassion, therefore, it’s useful to consider the “self” that is the focus of compassion, from an RFT perspective. Self-Compassion and Psychological Flexibility • Deictic relations are building blocks of how we experience the world, ourselves, and the flow of time. • Returning to an awareness of self-as-context offers us a non-attached and dis-identified relationship to our experiences. • This allows the habitual stimulus functions of our painful private events and stories to hold less influence over us. Self-Compassion and Psychological Flexibility • From the perspective of the I-Here-Nowness of being, I can view my own suffering as I might view the suffering of another, and be touched by the pain in that experience, without the dominant interference of my verbal learning history, with its potential for shaming selfevaluations (Vilardaga, 2009; Hayes, 2008). Formation of Self-as-Context: The No-Thing Self (Hayes, 2008) YOU HERE NOW I THERE THEN I-Here-Nowness of Perspective Taking Self-as-context Brain Development in Deep Historical Context Private Events and Brain Development in the context of Genotype, Phenotype, and Present Moment 1. “Old Brain” Emotional Responding: Overt Behavioral Responding: Relationship Behaviors: Anger, anxiety, sadness, joy, lust Fight, flight, withdraw, engage Sex, status, attachment, tribalism 2. “New Brain” Relational Framing, Imagination, fantasize, look back and forward, plan, Integration of mental abilities Self-awareness, self-identity, flexible perspective taking, selffeeling 3. “Social Brain” Need for affection and care Socially responsive, self-experience and motives Interaction of oldof and new psychologies Sources behaviour New Brain: Derived Relational Responding, Selfing Planning, Rumination, Old Brain: Emotions, Motives, Relationship Seeking, Safety Seeking Behaviors Understanding our Motives and Emotions Motives evolved because they help animals to survive and leave genes behind Emotions guide us to our goals and respond if we are succeeding or threatened There are three types of emotion regulation 1. Those that focus on threat and self-protection 2. Those that focus on doing and achieving 3. Those that focus on contentment and feeling safe Types of Affect Regulator Systems Content, safe, connected Drive, excite, vitality Non-wanting/ Affiliative focused Incentive/resourcefocused Safeness-kindness Wanting, pursuing, achieving, consuming Soothing Activating Threat-focused Protection and Safety-seeking Activating/inhibiting Anger, anxiety, disgust Self-Protection In species without attachment only 1-2% make it to adulthood to reproduce. Threats come from ecologies, food shortage, predation, injury, disease. At birth individuals must be able to “go it alone,” be mobile and disperse Dispersal and avoid others Protect and Comfort: Less ‘instinctive’ brain – post birth learning Compassion Process Giving/doing Receiving/soothing SBR/booth Validation Gratitude appreciation Mindful Acts of kindness Engagement with the feared Compassionate Self Threat Mindful awareness Triggers In the body Rumination Labelling Present Moment Contact Values Authorship Willingness Psychological Flexibility Commitment Defusion Self-As-Context Sympathy, Sensitivity Care For WellBeing Distress Tolerance Compassionate Flexibility Commitment to Compassionate Behavior Non-Judgment Empathy Present Moment Contact Values Authorship Willingness Psychological Flexibility Commitment Defusion Self-As-Context Contact with the present Build awareness of self-criticism/self-attack • Clients often do not even notice their self-evaluations. Methods: • Teach client to notice evaluation/judgment as it occurs in session (noticing antecedents) • Help clients to notice avoidance of shame as it occurs in session (noticing behavior) • Bring costs of self attack into the room (noticing consequences): – Read aloud self-attacking thoughts, but imagine she were saying them to a friend in the same position – Use a mirror when reading self-attacking thoughts to self – Act out self-attack in chair work 30 Acceptance Interventions Develop ability to acknowledge and embrace aspect of self that feels damaged, broken, unlovable, not-good-enough, and/or rejected Methods: • Examine workability of behaviors aimed at avoiding shame (anger, shutting down, addictive behavior). – How do they avoid feeling bad about themselves or feeling rejected? What happens in shame producing situations? • Bring process of shame and self-attacking into the room and improve ability to sit with it and with reaction to self-attack (usually with chair work) • Practice willingness in relating shameful experiences and secrets to trustworthy others (starting with therapist) 31 Defusion Develop distance, distinction from self-attacking thoughts. • Clients typically see critical view of self as normal, earned, or needed for motivation. Methods: • Imagery – imagine this critical self as if it were a person (include tone, size, facial expression, etc.). Give it a name. • Naming the critic – develop a name for the critical side of the self that has some endearing qualities • Act out criticizer as if it were another person • Many common defusion exercises can be helpful here 32 Self as context/flexible perspective taking Develop connection a sense of self that transcends our stories about self • Shame/self-criticism is fundamentally a problem with self/other as content Methods: • Work on letting go of attachment to self as content, e.g., self evaluations • Practice flexible perspective taking (loving kindness meditation, taking perspective of shamers, taking perspective of therapist, and caring others) • Physicalize self as content through chair exercises – Add a third chair, perhaps a compassion chair or observer chair for experiencing the ongoing dialogue. – Have client be the compassionate therapist in the third chair. What would that person say? • Use hierarchical framing to build sense of common humanity in suffering and normality of shame and fears 33 Flexible perspective taking Shift perspectives to expand possibilities • If your best friend was watching this interaction, what would they say? • If you were a therapist for a couple that acted this way, what would you think of them? What would you want for them? For him, for him? • If you were (someone client admires) [in the self chair], how would you act differently • If you were me and you heard what you are saying right now, what would you think? Notice change in perspective • When you look at this from another perspective, does it feel the same? Different? Do you see yourself the same way when you take these different perspectives? Combine with augmentals • If x (whatever the critic says) were not weighing you down, what would you be doing? What would you need from him/her to make that possible? • If x (whatever critic says) no longer held you back, what would you be doing? 34 Values Help person explore and define values toward self • Most people value empathy and connection, but fusion with self-concept impedes applying that to themselves Methods: • Empathy and compassion for self can emerge when the damage done by fusion with self-criticism is fully contacted • Elicit and define the kind of relationship person wants to have toward themselves 35 Committed action Help client take steps to act on values while practicing gentleness and compassion • Self-attacks often function as a way to coerce the self to act in line with self-standards and values (e.g., “buck up” and “push through it”). • Self-criticism makes it harder to take risks and learn, which inevitably involves failure and mistakes Methods: • Build commitment to practices of self-care and self-kindness • When exploring other kinds of valued actions, explore what kind of relationship person wants to have toward self as they do this--“and how do you want to be with yourself as you take these actions?” 36