A Divided Leadership

advertisement

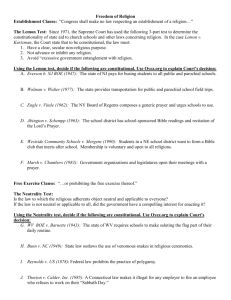

Battaglia 1 Washington Works Best When it is Either Blue or Red, Not Purple Since its inception, the Internet has been the topic of discussion. Many thought that since there was no owner of the Internet and no one actually regulated it, things should stay that way. Others agreed and went further, saying that censoring a form of speech and interaction like this would be contrary to the very First Amendment to the Constitution. It is the First Amendment for a reason; every American, past and present, holds this right close to their heart. It is one of many things that allow the citizens of the United States to be free citizens in the world today. America would not be the same if its people were not free to choose their own religion, say what they want and openly express themselves in the fashion of their choosing. A legitimate concern, nevertheless, had to do with protecting children from sexual predators and viewing obscene material on the Internet. Congress has attempted to act on these issues multiple times during two different presidencies. Some attempts succeeded but most failed because when it went to the Supreme Court the Justices would likely disagree. People always thought there needed to be a change; some thought it was because there was a Democratic President and Republican Congress at the time. Others went in a similar but different direction in that if the two were aligned some work could actually be done. When things change, people are a bit skeptical but still optimistic. The optimism grows as the familiarity strengthens and so does success. I will show that this is true regarding trying to protect our children from dangers on the Internet; that when you have the same party running Congress that you do running the White House, the Justices will be in your favor. Since no one owns the Internet, Congress took it upon itself to try to pass legislation that would regulate what children have access to on the Internet; but the American Civil Liberties Battaglia 2 Union, or ACLU, fought it.1 In 1996, behind Democratic President Clinton, the Republican-ran Congress passed the Communications Decency Act, or CDA, which was concerned with regulating what people could knowingly transmit to other people under the age of eighteen.2 It included anything that was “indecent transmission” and “patently offensive display” with a penalty of no more than two years in jail.3 This seemed like good legislation on the part of Congress; however, the ACLU took exception to this statute. They argued that the aforementioned terms were “unconstitutionally vague” and that it in reality restricted an adult’s ability to obtain or view mature content.4 Their basis for challenging the terms was that the level of obscenity was determined by “contemporary community standards” which they also argued was not clear in its definition.5 Because of these broad terms with uncertain definitions, the ACLU thought this legislation was unconstitutionally restricting adult access and transmission of information, contemporarily obscene or not.6 When brought to a district court, the judges ruled with the ACLU and, subsequently, Attorney General Janet Reno appealed to the Supreme Court.7 All nine justices sided with the ACLU and Justice John Paul Stevens wrote the opinion. The Court agreed that because the law did not specifically define what “indecent transmission” or “patently offensive display” meant, there was no explicit protection of adult access and transmission of information.8 In other words, there was no guarantee that this would have any 1 Lee Epstein and Thomas G. Walker, Constitutional Law For a Changing America: A Short Course (CQ Press, 2012), 473-4. 2 Epstein and Walker, Constitutional Law, 473-4. 3 Epstein and Walker, Constitutional Law, 473. 4 Epstein and Walker, Constitutional Law, 474. 5 Epstein and Walker, Constitutional Law, 474. 6 Epstein and Walker, Constitutional Law, 474. 7 Epstein and Walker, Constitutional Law, 474. 8 Epstein and Walker, Constitutional Law, 475. Battaglia 3 effect on the ability of adults to speak freely on the Internet. This decision had no reflection on the political views of the Justices. The Court concluded that this was not the most effective and least restrictive way of accomplishing the goal of Congress to protect what children can access on the Internet.9 This piece of legislation was flawed and too broad in its terms to make even the most conservative judge uphold its constitutionality. Congress was not pleased and tried again. In 1998, a different but still Republican dominated Congress passed another law similar to the CDA, the Child Online Protection Act, or COPA, and the ACLU responded again. This law made it illegal to distribute “any communication for commercial purposes that is available to any minor and that includes any material that is harmful to minors… [and] violators can face criminal prosecution with fines up to $50,000 a day.”10 This was different from the CDA, as COPA was more narrowly tailored towards the goal of protecting children. To distinguish what material may be harmful to minors, this act uses the Miller test from Miller v. California (1973), a case that involved a man sending out pamphlets to promote his adult book business.11 This test determines whether the average person takes the work as a whole to be “patently offensive by contemporary community standards as specifically defined by applicable state law.”12 A federal district court invalidated this measure much in the same fashion as the Supreme Court did for the CDA in Reno v. ACLU (1997), declaring that it would restrict otherwise legally accessible material to adults.13 A U.S. Court of Appeals concurred, stating that the Internet has such a 9 Epstein and Walker, Constitutional Law, 475. Epstein and Walker, Constitutional Law, 476. 11 Epstein and Walker, Constitutional Law, 476-7. 12 Epstein and Walker, Constitutional Law, 463. 13 Epstein and Walker, Constitutional Law, 476. 10 Battaglia 4 wide range of users geographically that there can be no regulation of where the information travels.14 This echoed what the Supreme Court had said in Reno, that anything available to mass population is judged by the standards of the community most offended.15 Having not exhausted all possible appeal processes, Congress was not about to give up. Five years after COPA’s initial creation, the new Attorney General, this time John Ashcroft, appealed to the Supreme Court for its implementation, but this too failed. Justice Clarence Thomas, who wrote the opinion, concluded that solely the “community standards” provision did not render COPA unconstitutional.16 Congress thought they fixed mistakes from the CDA and gave it a proper form in COPA because even three left-wing Justices voted in the majority, along with all of the right-wing Justices.17 The only dissenter was John Paul Stevens whom argued that the use of community standards on the Internet would become more harmful than its intention.18 He suggested that the Internet would become a “puritan village” and if so, the content some users have the legal right to post and view would be blocked and that would violate his or her First Amendment right.19 However, in the end they sent it back to the Third Circuit of Appeals for further review.20 This piece of legislation looked like it was never going to be fully implemented. 14 Epstein and Walker, Constitutional Law, 476-7. Epstein and Walker, Constitutional Law, 477. 16 “Ashcroft v. American Civil Liberties Union,” The OYEZ Project at IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law, accessed 12 March 2014, http://www.oyez.org/cases/2000-2009/2003/2003_03_218.html. 17 “Ashcroft v. American Civil Liberties Union.” 18 “Ashcroft v. American Civil Liberties Union.” 19 “Ashcroft v. American Civil Liberties Union.” 20 Epstein and Walker, Constitutional Law, 477. 15 Battaglia 5 The Court of Appeals unfortunately deemed it unconstitutional, this time because they concluded, the bill as a whole, was not the least restrictive way of protecting children from obscene material on the Internet.21 The judges concluded that if this act were to pass the strict scrutiny test and become legislation, which they thought was unlikely, it would still prohibit people from posting something online that a legal adult has the right to post and view.22 When this came back to the Supreme Court, the Justices split their decisions. The majority, which included three liberal Justices and two right-wing Justices, favored the ACLU, agreeing with the Third Circuit that COPA was not the least restrictive way of protecting children.23 Justice Anthony Kennedy suggested using software to filter everything that comes in, not everything that goes out.24 This made sense; not allowing someone to use his or her voice on the Internet is more restricting than not allowing someone to view or listen to what is already on the Internet. Not coincidentally, this idea was similar to a case that was decided the year before in United States v. American Library Association (2003). With a new conservative President, George W. Bush, came a new Congress that was playing hardball this time, when they tried to pass a law that would withhold federal funding from libraries that did not “use ‘filtering’ software to block ‘visual depictions’” that they did not want children to view. 25 This seemed to be the most aggressive attempt yet. This act, called the Children’s Internet Protection Act, or CIPA, passed in 2000, required all schools and public libraries to use software on their computers that would block certain websites from being 21 Epstein and Walker, Constitutional Law, 477. “Ashcroft v. American Civil Liberties Union.” 23 Epstein and Walker, Constitutional Law, 477. 24 Epstein and Walker, Constitutional Law, 477. 25 Epstein and Walker, Constitutional Law, 477. 22 Battaglia 6 viewed.26 In short, if a child could access the computer and use the Internet, the software needed to be installed on that computer. This also came with an incentive; if the schools and libraries complied, then they would receive discounts from what is called the E-Rate program.27 The funding from the E-Rate program public libraries and schools collect pay for the services and opportunities that each offer their patrons. It pays for the computers children and adults use; it also pays for access to the Internet. Therefore, it would make sense to comply with this because not only would it, in theory, block children from stumbling upon websites they are not supposed to be on; it would also allow them a little flexibility with their budgets. The American Library Association, or ALA, and other groups disagreed. The ALA and its allies felt that CIPA would infringe upon some patrons’ First Amendment rights, though they had a weak argument, and took it to the courts.28 During the oral argument, the CIPA proponents argued that this was no more infringing upon adults’ First Amendment rights as not providing pornographic readings on their shelves.29 This is a good point; a person will not find any pornographic material in a public library, print or electronic. When asked if the filter could be removed on his or her account as per request of a verifiable adult patron, the United States Solicitor General, Theodore B. Olson, responded that it could and “Children’s Internet Protection Act,” Federal Communications Commission, accessed 13 March 2014, http://www.fcc.gov/guides/childrens-internet-protection-act.html. 27 “Children’s Internet Protection Act.” 28 “United States v. American Library Association,” The OYEZ Project at IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law, accessed 13 March 2014, http://www.oyez.org/cases/2000-2009/2002/2002_02_361#chicago.html. 29 “United States v. American Library Association Oral Argument Transcript,” The OYEZ Project at IIT ChicagoKent College of Law, accessed 13 March 2014, http://www.oyez.org/cases/20002009/2002/2002_02_361#transcript-text59114.html. 26 Battaglia 7 the patron did not need to explain why he or she asked.30 An issue that came up was the length of delay when removing filters and the difficulty involved in doing so.31 The CIPA proponents responded by comparing removing the filters to having to order another book that was not on the shelf or transferring a book from another library.32 The ALA did not really seem to have a point in challenging this legislation because although it did prevent minors from viewing adult material, unlike the CDA and COPA, it did not prevent adults from viewing such material. It looked like CIPA allies had a good comeback for every attack and might actually withstand yet another challenge. In the decision, the Court stated that since government funds allow public libraries to function in the way that they do, the government is allowed to “broadly define… [the libraries’] limits,” as in Rust v. Sullivan (1990). In the six-to-three ruling, the majority contained all of the conservative judges and one liberal. This was a big win for Congress. It was their first successful legislation that weathered the storm that is the Supreme Court. One very important step made towards Congress’ goal of protecting children from the horror of the Internet. This is a remarkable outcome despite the fact the Justices stayed the same through the change in the Oval Office. The court case Rust v. Sullivan set the precedent for governments’ restrictions on organizations that receive its funds back when conservatives ran the show again and George Bush Sr. was in office and Republicans dominated Congress. “United States v. American Library Association Oral Argument Transcript.” “United States v. American Library Association Oral Argument Transcript.” 32 “United States v. American Library Association Oral Argument Transcript.” 30 31 Battaglia 8 Public family planning services receive their funding from the government, known as Title X funds.33 In the early ‘90s, the Department of Health and Human Services put restrictions on what specifically these funds could be used for.34 One of the things they did not want the money to go towards was abortion.35 Because the government did not outright support the right to abort a fetus, they did not want their money used for materials and services to perform said operation. This was a split decision for the Justices as they ruled 5-4 in favor of Sullivan, concluding that if the government provides for one “protected right,” family planning, it is not necessary that they provide for “analogous counterpart rights” such as abortion; they ultimately deferred this case back to “the expertise of the administrative agency.”36 This reflects the rightwing atmosphere at the time. In fact, three of the four more conservative Justices voted in the majority.37 An important precedent was set with this ruling. Any program that received funding was required to use it as the government intended it to be used. Government funding has since had a Republican tint. The Justices in the majority seemed to be in accordance with the political party that occupied the White House. The CDA, which came out of a Republican Congress, was a unanimous no in the Supreme Court when Clinton was President. The initial COPA ruling, though sent back and also the result of a Republican Congress, was a yes, with five conservatives in the majority and three liberals, still with Clinton. However, in the second time around, some “Rust v. Sullivan,” OYEZ Project at IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law, accessed 13 March 2014, http://www.oyez.org/cases/1990-1999/1990/1990_89_1391.html. 34 “Rust v. Sullivan.” 35 “Rust v. Sullivan.” 36 “Rust v. Sullivan.” 37 “Rust v. Sullivan.” 33 Battaglia 9 Justices changed their minds. Out of the five in the majority who ruled no this time, three were liberal. Republicans already had control of Congress and made little progress. They were hoping the change in President would help their cause. In the CIPA case, after Bush was elected, the law was upheld and the majority contained four conservative Justices and one left-wing. Only once the party that had the upper hand in Congress also had the seat in the White House, did legislation successfully pass regarding some kind of regulation of the Internet. While Clinton was President, the liberal judges struck down both Republican efforts to regulate the Internet. After George W. Bush took office, he and his Republican allies must have made the Republican Justices feel comfortable enough to stand up and help their cause. Battaglia 10 Works Cited Ashcroft v. American Civil Liberties Union, 535 U.S. 564 (2002). Ashcroft v. American Civil Liberties Union, 542 U.S. 656 (2004). "Ashcroft v. American Civil Liberties Union," The Oyez Project at IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law, accessed March 14, 2014, http://www.oyez.org/cases/2000-2009/2003/2003_03_218. Epstein, Lee and Thomas G. Walker. Constitutional Law for A Changing America: A Short Course .CQ Press, 2012. Federal Communications Commission. “Children’s Online Protection Act.” Accessed March 13 2014. http://www.fcc.gov/guides/childrens-internet-protection-act.html. Rust v. Sullivan, 500 U.S. 173 (1991). "Rust v. Sullivan," The Oyez Project at IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law, accessed March 18, 2014, http://www.oyez.org/cases/1990-1999/1990/1990_89_1391. United States v. American Library Association, 539 U.S. 194 (2003). "United States v. American Library Association," The Oyez Project at IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law, accessed March 16, 2014, http://www.oyez.org/cases/20002009/2002/2002_02_361.