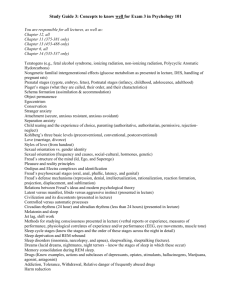

File - VIRTUAL CLASS by Creative Alliance Services

advertisement

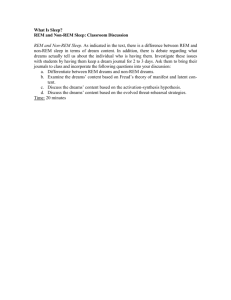

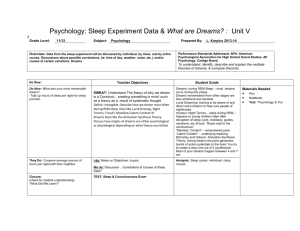

DREAM THEORIES STATES OF CONSCIOUSNESS Unconscious Wish Fulfillment Theory • • • • • • • Freud: Dreams as the Road to the Unconscious Mind: In his book The Interpretation of Dreams, Sigmund Freud suggested that the content of dreams is related to wish fulfillment. Freud believed that the manifest content of a dream, or the actually imagery and events of the dream, served to disguise the latent content, or the unconscious wishes of the dreamer. Freud also described four elements of this process that he referred to as 'dream work': Condensation – Many different ideas and concepts are represented within the span of a single dream. Information is condensed into a single thought or image. Displacement – This element of dream work disguises the emotional meaning of the latent content by confusing the important and insignificant parts of the dream. Symbolization – This operation also censors the repressed ideas contained in the dream by including objects that are meant to symbolize the latent content of the dream. Secondary Revision – During this final stage of the dreaming process, Freud suggested that the bizarre elements of the dream are reorganized in order to make the dream comprehensible, thus generating the manifest content of the dream. • First and foremost in dream theory is Sigmund Freud. Falling into the psychological camp, Dr. Freud's theories are based on the idea of repressed longing -- the desires that we aren't able to express in a social setting. Dreams allow the unconscious mind to act out those unacceptable thoughts and desires. For this reason, his theory about dreams focuses primarily on sexual desires and symbolism. • For example, any cylindrical object in a dream represents the penis, while a cave or an enclosed object with an opening represents the vagina. Therefore, to dream of a train entering a tunnel would represent sexual intercourse. According to Freud, this dream indicates a suppressed longing for sex. Freud lived during the sexually repressed Victorian era, which in some way explains his focus. Still, he did once comment that, "Sometimes, a cigar is just a cigar." Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious: • While Carl Jung shared some commonalities with Freud, he felt that dreams were more than an expression of repressed wishes. Jung suggested that dreams revealed both the personal and collective unconscious and believed that dreams serve to compensate for parts of the psyche that are underdeveloped in waking life. However, later research by Hall discovered that the traits people exhibit while they awake are also expressed in dreams. • Jung also suggested that archetypes such as the anima, the shadow and the animus are often represented symbolic objects or figures in dreams. These symbols, he believed, represented attitudes that are repressed by the conscious mind. Unlike Freud, who often suggested that specific symbols represents specific unconscious thoughts, Jung believed that dreams can be highly personal and that interpreting these dreams involved knowing a great deal about the individual dreamer. • Carl Jung studied under Freud but soon decided his own ideas differed from Freud's to the extent that he needed to go in his own direction. He agreed with the psychological origin of dreams, but rather than saying that dreams originated from our primal needs and repressed wishes, he felt that dreams allowed us to reflect on our waking selves and solve our problems or think through issues. Activation - Synthesis Theory • The activation-synthesis model of dreaming was first proposed by J. Allan Hobson and Robert McClarley in 1977. According to this theory, circuits in the brain become activated during REM sleep, which causes areas of the limbic system involved in emotions, sensations and memories, including the amygdala and hippocampus, to become active. The brain synthesizes and interprets this internal activity and attempts to find meaning in these signals, which results in dreaming. This model suggests that dreams are a subjective interpretation of signals generated by the brain during sleep. • While this theory suggests that dreams are the result of internally generated signals, Hobson does not believe that dreams are meaningless. Instead, he suggests that dreaming is "…our most creative conscious state, one in which the chaotic, spontaneous recombination of cognitive elements produces novel configurations of information: new ideas. While many or even most of these ideas may be nonsensical, if even a few of its fanciful products are truly useful, our dream time will not have been wasted." • around 1973, researchers Allan Hobson and Robert McCarley set forth another theory that threw out the old psychoanalytical ideas. Their research on what was going in the brain during sleep gave them the idea that dreams were simply the result of random electrical brain impulses that pulled imagery from traces of experience stored in the memory. They hypothesize that these images don't form the stories that we remember as our dreams. Instead, our waking minds, in trying to make sense of the imagery, create the stories without our even realizing it -- simply because the brain wants to make sense of what it has experienced. While this theory, known as the activation-synthesis hypothesis, created a big rift in the dream research arena because of its leap away from the accepted theories, it has withstood the test of time and is still one of the more prominent dream theories. Other Theories of Dreams: • • Many other theories have been suggested to account for the occurrence and meaning of dreams. The following are just of few of the proposed ideas: One theory suggests that dreams are the result of our brains trying to interpret external stimuli during sleep. For example, the sound of the radio may be incorporated into the content of a dream • Another theory uses a computer metaphor to account for dreams. According to this theory, dreams serve to 'clean up' clutter from the mind, much like clean-up operations in a computer, refreshing the mind to prepare for the next day • Yet another model proposes that dreams function as a form of psychotherapy. In this theory, the dreamer is able to make connections between different thoughts and emotions in a safe environment 7. • A contemporary model of dreaming combines some elements of various theories. The activation of the brain creates loose connections between thoughts and ideas, which are then guided by the emotions of the dreamer 8. DREAM PHENOMENA • Incorporation of reality • • During the night, many external stimuli may bombard the senses, but the brain often interprets the stimulus and makes it a part of a dream to ensure continued sleep.Dream incorporation is a phenomenon whereby an actual sensation, such as environmental sounds, are incorporated into dreams, such as hearing a phone ringing in a dream while it is ringing in reality or dreaming of urination while wetting the bed. The mind can, however, awaken an individual if they are in danger or if trained to respond to certain sounds, such as a baby crying. The term "dream incorporation" is also used in research examining the degree to which preceding daytime events become elements of dreams. Recent studies suggest that events in the day immediately preceding, and those about a week before, have the most influence. • Apparent precognition of real events • • According to surveys, it is common for people to feel their dreams are predicting subsequent life events. Psychologists have explained these experiences in terms of memory biases, namely a selective memory for accurate predictions and distorted memory so that dreams are retrospectively fitted onto life experiences. The multi-faceted nature of dreams makes it easy to find connections between dream content and real events. In one experiment, subjects were asked to write down their dreams in a diary. This prevented the selective memory effect, and the dreams no longer seemed accurate about the future. Another experiment gave subjects a fake diary of a student with apparently precognitive dreams. This diary described events from the person's life, as well as some predictive dreams and some non-predictive dreams. When subjects were asked to recall the dreams they had read, they remembered more of the successful predictions than unsuccessful ones. • Lucid dreaming • • • Main article: Lucid dreaming Lucid dreaming is the conscious perception of one's state while dreaming. In this state the dreamer may often (but not always) have some degree of control over their own actions within the dream or even the characters and the environment of the dream. Dream control has been reported to improve with practiced deliberate lucid dreaming, but the ability to control aspects of the dream is not necessary for a dream to qualify as "lucid" — a lucid dream is any dream during which the dreamer knows they are dreaming. The occurrence of lucid dreaming has been scientifically verified. Oneironaut is a term sometimes used for those who lucidly dream. • Dreams of absent-minded transgression • Dreams of absent-minded transgression (DAMT) are dreams wherein the dreamer absentmindedly performs an action that he or she has been trying to stop (one classic example is of a quitting smoker having dreams of lighting a cigarette). Subjects who have had DAMT have reported waking with intense feelings of guilt. One study found a positive association between having these dreams and successfully stopping the behavior. • Recalling dreams • • The recall of dreams is extremely unreliable, though it is a skill that can be trained. Dreams can usually be recalled if a person is awakened while dreaming. Women tend to have more frequent dream recall than men. Dreams that are difficult to recall may be characterized by relatively little affect, and factors such as salience, arousal, and interference play a role in dream recall. Often, a dream may be recalled upon viewing or hearing a random trigger or stimulus. A dream journal can be used to assist dream recall, for psychotherapy or entertainment purposes. For some people, vague images or sensations from the previous night's dreams are sometimes spontaneously experienced in falling asleep. However they are usually too slight and fleeting to allow dream recall. At least 95% of all dreams are not remembered. Certain brain chemicals necessary for converting short-term memories into long-term ones are suppressed during REM sleep. Unless a dream is particularly vivid and if one wakes during or immediately after it, the content of the dream is not remembered. • Déjà vu • One theory of déjà vu attributes the feeling of having previously seen or experienced something to having dreamt about a similar situation or place, and forgetting about it until one seems to be mysteriously reminded of the situation or the place while awake. • Daydreaming • • A daydream is a visionary fantasy, especially one of happy, pleasant thoughts, hopes or ambitions, imagined as coming to pass, and experienced while awake. There are many different types of daydreams, and there is no consistent definition amongst psychologists. The general public also uses the term for a broad variety of experiences. Research by Harvard psychologist Deirdre Barrett has found that people who experience vivid dream-like mental images reserve the word for these, whereas many other people refer to milder imagery, realistic future planning, review of past memories or just "spacing out"--i.e. one's mind going relatively blank—when they talk about "daydreaming." While daydreaming has long been derided as a lazy, non-productive pastime, it is now commonly acknowledged that daydreaming can be constructive in some contexts. There are numerous examples of people in creative or artistic careers, such as composers, novelists and filmmakers, developing new ideas through daydreaming. Similarly, research scientists, mathematicians and physicists have developed new ideas by daydreaming about their subject areas. • Hallucination • A hallucination, in the broadest sense of the word, is a perception in the absence of a stimulus. In a stricter sense, hallucinations are perceptions in a conscious and awake state, in the absence of external stimuli, and have qualities of real perception, in that they are vivid, substantial, and located in external objective space. The latter definition distinguishes hallucinations from the related phenomena of dreaming, which does not involve wakefulness. • Nightmares • A nightmare is an unpleasant dream that can cause a strong negative emotional response from the mind, typically fear and/or horror, but also despair, anxiety and great sadness. The dream may contain situations of danger, discomfort, psychological or physical terror. Sufferers usually awaken in a state of distress and may be unable to return to sleep for a prolonged period of time. • Night terrors • A night terror, also known as a sleep terror or pavor nocturnus, is a parasomnia disorder that predominantly affects children, causing feelings of terror or dread. Night terrors should not be confused with nightmares, which are bad dreams that cause the feeling of horror or fear. SLEEP DISTURBANCES SLEEP DISORDER • A sleep disorder, or somnipathy, is a medical disorder of the sleep patterns of a person or animal. Some sleep disorders are serious enough to interfere with normal physical, mental and emotional functioning. Polysomnography is a test commonly ordered for some sleep disorders. • Disruptions in sleep can be caused by a variety of issues, from teeth grinding (bruxism) to night terrors. When a person suffers from difficulty in sleeping with no obvious cause, it is referred to as insomnia.[1] In addition, sleep disorders may also cause sufferers to sleep excessively, a condition known as hypersomnia. Management of sleep disturbances that are secondary to mental, medical, or substance abuse disorders should focus on the underlying conditions. Common Disorders • Primary insomnia: Chronic difficulty in falling asleep and/or maintaining sleep when no other cause is found for these symptoms. • Bruxism: Involuntarily grinding or clenching of the teeth while sleeping. • Delayed sleep phase syndrome (DSPS): inability to awaken and fall asleep at socially acceptable times but no problem with sleep maintenance, a disorder of circadian rhythms. (Other such disorders are advanced sleep phase syndrome (ASPS), non-24-hour sleep-wake syndrome (Non-24), and irregular sleep wake rhythm, all much less common than DSPS, as well as the transient jet lag and shift work sleep disorder.) • Hypopnea syndrome: Abnormally shallow breathing or slow respiratory rate while sleeping. • Narcolepsy: Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) often culminating in falling asleep spontaneously but unwillingly at inappropriate times. • Cataplexy: a sudden weakness in the motor muscles that can result in collapse to the floor. • Night terror: Pavor nocturnus, sleep terror disorder: abrupt awakening from sleep with behavior consistent with terror. • Parasomnias: Disruptive sleep-related events involving inappropriate actions during sleep; sleep walking and night-terrors are examples. • Periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD): Sudden involuntary movement of arms and/or legs during sleep, for example kicking the legs. Also known as nocturnal myoclonus. See also Hypnic jerk, which is not a disorder. • Rapid eye movement behavior disorder (RBD): Acting out violent or dramatic dreams while in REM sleep (REM sleep disorder or RSD) • Restless legs syndrome (RLS): An irresistible urge to move legs. RLS sufferers often also have PLMD. Situational circadian rhythm sleep disorders: shift work sleep disorder (SWSD) and jet lag. • Sleep apnea, and mostly obstructive sleep apnea: Obstruction of the airway during sleep, causing lack of sufficient deep sleep; often accompanied by snoring. Other forms of sleep apnea are less common. The air is blocked from entering into the lungs, causing the individual to unconsciously gasp for air. The individual will pause for an average of ten seconds in order to breathe. This is commonly found in overweight, middle-aged men but is also found in people who have suffered from stroke. • Sleep paralysis: is characterized by temporary paralysis of the body shortly before or after sleep. Sleep paralysis may be accompanied by visual, auditory or tactile hallucinations. Not a disorder unless severe. Often seen as part of narcolepsy. • Sleepwalking or somnambulism: Engaging in activities that are normally associated with wakefulness (such as eating or dressing), which may include walking, without the conscious knowledge of the subject. • Nocturia: A frequent need to get up and go to the bathroom to urinate at night. It differs from Enuresis, or bed-wetting, in which the person does not arouse from sleep, but the bladder nevertheless empties.[2] Somniphobia: A cause of sleep deprivation. • Somniphobia is a dread/ fear of falling asleep or going to bed. Signs of illness include anxiety and panic attacks during attempts to sleep and before it. SLEEPING BETTER How to Sleep Better • Tip 1: Keep a regular sleep schedule Getting back in sync with your body’s natural sleep– wake cycle—your circadian rhythm—is one of the most important strategies for achieving good sleep. If you keep a regular sleep schedule, going to bed and getting up at the same time each day, you will feel much more refreshed and energized than if you sleep the same number of hours at different times. This holds true even if you alter your sleep schedule by only an hour or two. Consistency is important. • • • • • Set a regular bedtime. Go to bed at the same time every night. Choose a time when you normally feel tired, so that you don’t toss and turn. Try not to break this routine on weekends when it may be tempting to stay up late. If you want to change your bedtime, help your body adjust by making the change in small daily increments, such as 15 minutes earlier or later each day. Wake up at the same time every day. If you’re getting enough sleep, you should wake up naturally without an alarm. If you need an alarm clock to wake up on time, you may need to set an earlier bedtime. As with your bedtime, try to maintain your regular wake–time even on weekends. Nap to make up for lost sleep. If you need to make up for a few lost hours, opt for a daytime nap rather than sleeping late. This strategy allows you to pay off your sleep debt without disturbing your natural sleep–wake rhythm, which often backfires in insomnia and throws you off for days. Be smart about napping. While taking a nap can be a great way to recharge, especially for older adults, it can make insomnia worse. If insomnia is a problem for you, consider eliminating napping. If you must nap, do it in the early afternoon, and limit it to thirty minutes. Fight after–dinner drowsiness. If you find yourself getting sleepy way before your bedtime, get off the couch and do something mildly stimulating to avoid falling asleep, such as washing the dishes, calling a friend, or getting clothes ready for the next day. If you give in to the drowsiness, you may wake up later in the night and have trouble getting back to sleep. Tip 2: Naturally regulate your sleep-wake cycle • Melatonin is a naturally occurring hormone that helps regulate your sleep-wake cycle. Melatonin production is controlled by light exposure. Your brain should secrete more in the evening, when it’s dark, to make you sleepy, and less during the day when it’s light and you want to stay awake and alert. However, many aspects of modern life can disrupt your body’s natural production of melatonin and with it your sleep-wake cycle. • Spending long days in an office away from natural light, for example, can impact your daytime wakefulness and make your brain sleepy. Then bright lights at night—especially from hours spent in front of the TV or computer screen—can suppress your body’s production of melatonin and make it harder to sleep. However, there are ways for you to naturally regulate your sleepwake cycle, boost your body’s production of melatonin, and keep your brain on a healthy schedule. Increase light exposure during the day • Remove your sunglasses in the morning and let light onto your face. • Spend more time outside during daylight. Try to take your work breaks outside in sunlight, exercise outside, or walk your dog during the day instead of at night. • Let as much light into your home/workspace as possible. Keep curtains and blinds open during the day, move your desk closer to the window. • If necessary, use a light therapy box. A light therapy box can simulate sunshine and can be especially useful during short winter days when there’s limited daylight. Boost melatonin production at night • Turn off your television and computer. Many people use the television to fall asleep or relax at the end of the day. Not only does the light suppress melatonin production, but television can actually stimulate the mind, rather than relaxing it. Try listening to music or audio books instead, or practicing relaxation exercises. If your favorite TV show is on late at night, record it for viewing earlier in the day. • Don’t read from a backlit device at night (such as an iPad). If you use a portable electronic device to read, use an eReader that is not backlit, i.e. one that requires an additional light source such as a bedside lamp. • Change your light bulbs. Avoid bright lights before bed, use low-wattage bulbs instead. • When it’s time to sleep, make sure the room is dark. The darker it is, the better you’ll sleep. Cover electrical displays, use heavy curtains or shades to block light from windows, or try an eye mask to cover your eyes. • Use a flashlight to go to the bathroom at night. As long as it’s safe to do so, keep the light to a minimum so it will be easier to go back to sleep. Tip 3: Create a relaxing bedtime routine • • • • • • Make your bedroom more sleep friendly Keep noise down. If you can’t avoid or eliminate noise from barking dogs, loud neighbors, city traffic, or other people in your household, try masking it with a fan, recordings of soothing sounds, or white noise. You can buy a special sound machine or generate your own white noise by setting your radio between stations. Earplugs may also help. Keep your room cool. The temperature of your bedroom also affects sleep. Most people sleep best in a slightly cool room (around 65° F or 18° C) with adequate ventilation. A bedroom that is too hot or too cold can interfere with quality sleep. Make sure your bed is comfortable. You should have enough room to stretch and turn comfortably. If you often wake up with a sore back or an aching neck, you may need to invest in a new mattress or a try a different pillow. Experiment with different levels of mattress firmness, foam or egg crate toppers, and pillows that provide more support. Reserve your bed for sleeping and sex If you associate your bed with events like work or errands, it will be harder to wind down at night. Use your bed only for sleep and sex. That way, when you go to bed, your body gets a powerful cue: it’s time to nod off.