Chapter 6: Money and Prices in the Long Run

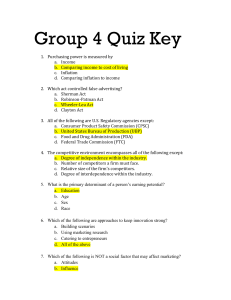

advertisement